A new exhibition at the Aušros Museum in Šiauliai, Lithuania tells the story of how a remarkable school in the southern Latvian city of Jelgava (at that time, most often known by its German name, Mitau), became a place of disproportionate importance for two Baltic nations – not only Latvia, but also Lithuania. A striking number of the leading figures in the formation of the two states were educated at the school, including the first president of the interwar Lithuanian republic, Antanas Smetona, and the first Latvian president, Jānis Čakste.

Both countries were part of the Russian Empire during this period, but Russian rule in Lithuania at the time was rather harsher, largely a result of its rebelliousness in the middle of the century. A ban on printing in the Lithuanian language using Latin characters had been imposed after the unsuccessful uprising of 1863 in Lithuania, and remained in force until 1904. Education in Lithuania was also conducted mostly in Russian, with teaching in Lithuanian forbidden. By contrast, in most of modern-day Latvia, teaching in high schools and universities was in German – since most of the land-owning and aristocratic classes were German-speaking.

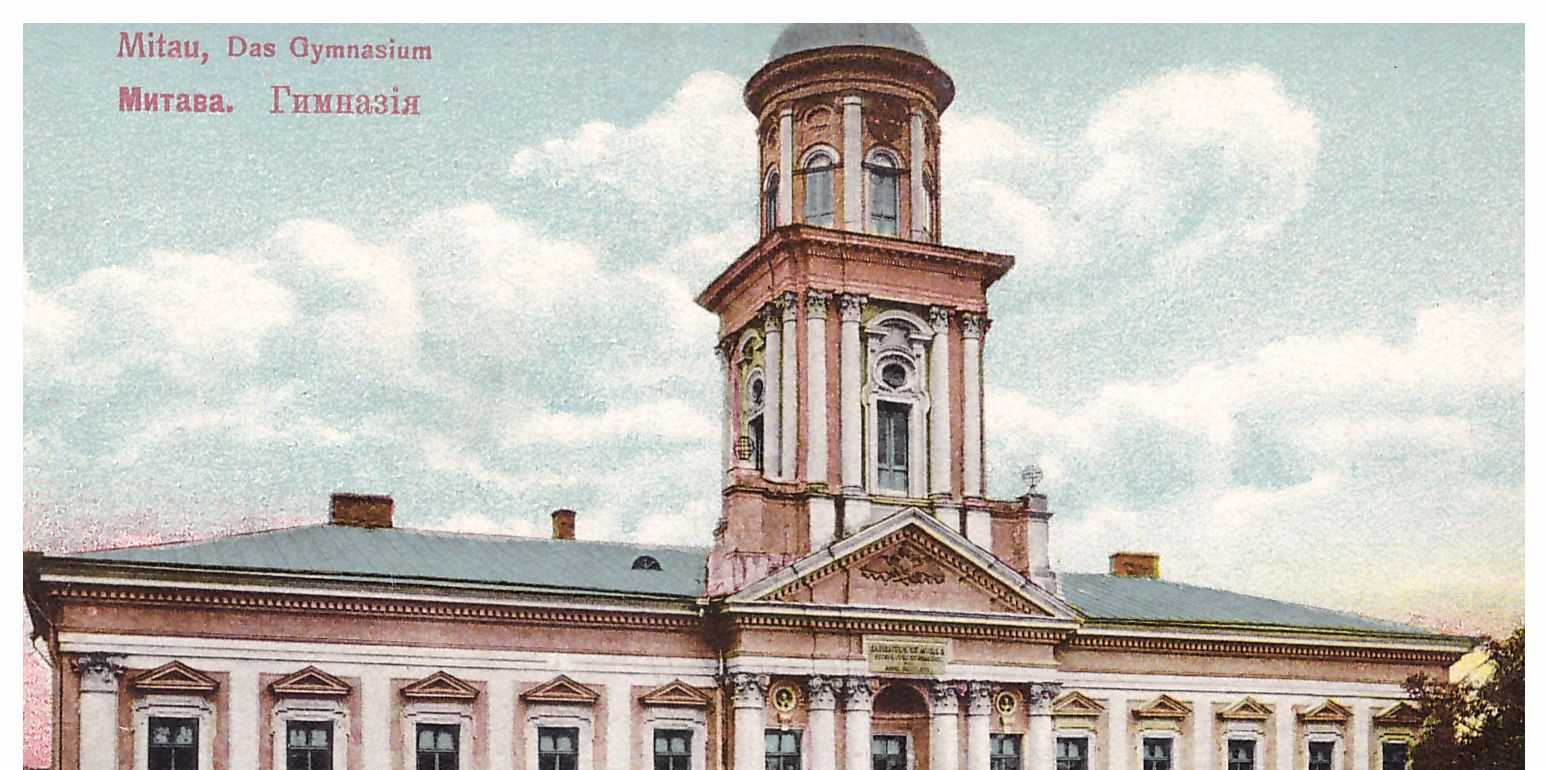

There were few educational options for those living in the north of Lithuania at the time – a college in Kražiai had operated for a few decades but closed in 1842. In 1853, a gymnasium opened in Šiauliai, but teaching was exclusively in Russian and they were not able to take all applicants. The gymnasium (as a selective secondary school is called under the German system) in Jelgava was opened in 1775, at that time the capital of a semi-independent state, the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (which today is roughly covered by the Latvian provinces of Kurzeme and Zemgale).

But by the mid-19th century, Jelgava was simply the largest city in the Courland governorate of the Russian Empire, close to the border of the governorate of Kovno (now Kaunas in Lithuania).

Partly due to the existence of the gymnasium, Jelgava became a centre of Lithuanian culture in the Russian Empire in the final decades of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. By 1885 a Catholic charitable society was operating, in which Lithuanians participated (unlike the mostly Lutheran local Latvians and Germans, Lithuanians were overwhelmingly Catholic). In 1902, a Lithuanian mutual help society was formed in the city, and three years later the first theatre performance was organised in Lithuanian. A Lithuanian social democratic group was formed in 1905, and the same year a delegation of Lithuanians from Jelgava attended the Great Seimas of Vilnius, a national assembly at which a decision was made to demand extensive political autonomy for Lithuania.

Lithuanians were attracted to Jelgava not only by the educational opportunities, but also by the active cultural life. In 1888, at Jelgava Gymnasium, a Lithuanian youth society was formed, called “Kūdikis” – the aims of the society were to learn about Lithuanian culture and the Lithuanian language, as well as to nurture love for their homeland and increase national consciousness. Members of the society read and circulated banned Lithuanian-language publications. Many students remained in the city after graduating, and by the start of the 20th century, a quarter of the total population of Jelgava was Lithuanian.

However, the Russification drive in the Baltic provinces during the last decades of the 19th century also affected Jelgava. The language of instruction was switched from German to Russian in 1890. A further Russification measure, passed in 1896 caused particular trouble, especially among the Lithuanian population. It governed the language in which the inhabitants of the empire should pray; under the measure, Lutherans could continue praying in their native tongue, whether German or Latvian, but Catholics would be forced to pray in the same language as Orthodox believers: Russian. Lithuanians, who at that point formed the majority of the school’s students, were outraged – and those in the older classes and members of the “Kūdikis” society resisted. A student, Juozas Tūbelis (a future prime minister of Lithuania), was removed from his position for his refusal to comply, and as many as 50 Lithuanians were kicked out of the school over their refusal to read prayers in Russian. Many were readmitted the following year, but Tūbelis and Lithuania’s future president, Antanas Smetona, never returned.

Jelgava was also highly important for the Republic of Latvia, which it became part of in 1918, as part of the province of Zemgale. As well as many important cultural and political figure, two of the four presidents of the country during its interwar period of independence studied at the gymnasium – Jānis Čakste and Alberts Kviesis.

We’ve highlighted six figures, both Latvian and Lithuanian, who studied at Jelgava who subsequently achieved great significance in the history of their countries.

Antanas Smetona

Born in Taujėnai in central Lithuania into a family of farmers, Smetona studied in Jelgava from 1893 to 1897, and afterwards in St. Petersburg. While in Russia he was arrested and imprisoned for his participation in student protests, and later for involvement in a ring smuggling banned Lithuanian-language books. On 4th April 1919, he was chosen by the newly formed State Council of Lithuania as the first president of the Republic of Lithuania. He became president again in 1926 after a coup overthrew the elected government led by Kazys Grinius.

In 1940, when the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania, feeling that the government would not support armed resistance, Smetona left Lithuania for Germany, and from there he travelled to Switzerland and then the USA, where he died in 1944 in a house fire.

Jānis Čakste

Jānis Čakste was the first president of independent Latvia. Born in 1859 in Dobele district, not far from Jelgava, he studied at the gymnasium from 1875 to 1882, before leaving for Moscow, where he studied as a lawyer, graduating in 1886. While in Moscow he founded a Latvian student society, as well as a monthly publication, Austrums. After his return to Latvia, he worked as a secretary for the prosecutor’s office of the Courland Governorate, then as a lawyer in Jelgava. In 1895, he was the main organiser of the Fourth Latvian Song and Dance Festival, which took place in Jelgava. Elected to the Russian State Duma in 1906 as a representative for the Courland Governorate (which included Jelgava); the same year, along with 165 other deputies, he signed the Vyborg Manifesto, which called for non-payment of taxes and evasion of conscription. For his part in this, he received a three-month prison sentence.

In November 1918, Čakste was chosen as chairman by the People’s Council of Latvia. The following year, he led the Latvian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, where the borders of post-war Europe were drawn up. In 1922, he was elected as the first ever President of the Republic of Latvia; in 1925, he was re-elected for a second term. Čakste died in 1927 and is buried in the Meža Cemetery in Riga.

Jonas Šliupas was a Lithuanian doctor and politician. He studied in Jelgava between 1873 and 1880, and later worked as editor of the Lithuanian magazine Aušra (Morning Star) before living and studying in Maryland in the USA. While in the US, he was an active member of Lithuanian societies, and published and edited Lithuanian texts. Following the establishment of the Baltic states, he was chosen as a representative of Lithuania in Latvia and Estonia.

Šliupas’s experiences in Jelgava gave him an interest in the history of Latvia, and in its relationship with his native country. He was a lifelong advocate of a union between the two Baltic nations – in 1918 a collection of lectures and writings was published entitled “the Lithuanian-Latvian Republic and the Union of the Northern Peoples”.

After leaving Latvia, he continued to work towards this idea, and expanded his idea of a northern federation, which he said would be “a collective federal state, to which would belong blood relations: Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Prussians (up to the River Vistula) and Belarusians (the old Gotvingians or Jatvingians up to Pinsk).”

Alberts Kviesis

Alberts Kviesis was a lawyer who became President of Latvia. Born in Jelgava district, Kviesis received his education at Jelgava Gymnasium between 1894 and 1902. After leaving the school, Kviesis continued his studies at Tartu University (at that time known as Dorpat) in Estonia, where he joined the Latvian student society Lettonia. After graduating, he returned to Jelgava, where he worked as a lawyer, and was involved in Latvian societies and the Red Cross.

In the first years after the creation of the Republic of Latvia, he worked actively to create the legal system for the new country.

He contested the 1927 presidential election, but Gustavs Zemgals was chosen instead. But three years later, he was elected as President of Latvia, becoming the country’s third president since independence, and re-elected in 1933. Kārlis Ulmanis came to power in a coup in 1934, but Kviesis remained in his position until the expiration of his term in 1936, although he lost any real power. It was Kviesis who officially opened the Freedom Monument in Riga in 1936

Vytautas Petrulis

Petrulis was a Lithuanian finance specialist and politician. Born in northern Lithuania in 1890, he studied at Jelgava gymnasium – but when he was in the top class, he was expelled from the school, following his refusal to pray in Russian, as the new law specified. After this, he graduated from Moscow Institute of Commerce. During the first years of World War I, he was involved in the Moscow branch of the society for the support of injured Lithuanian soldiers.

In 1918, he was invited to become a member of the newly formed State Council of Lithuania, and in 1919, to become finance minister. During his term in office, the national currency, the litas, was introduced. He served as finance minister under four governments, and was prime minister of Lithuania for six months in 1925. In 1932, he was imprisoned after being accused of conducting secret talks with Poland – a state which at that time Lithuania had no diplomatic relations with due to the dispute over Vilnius (then under Polish control and known internationally as Wilno) – but was freed after a month and a half following an appeal; however, he was barred from political office and didn’t return to public life until 1937. Petrulis became one of the first victims of the NKVD in Lithuania – in July 1940, following the Soviet occupation, he was imprisoned in Kaunas, then sent to Komi in the far north of Russia the following year, where he was shot.

In 1932, Petrulis was imprisoned after being accused of conducting secret talks with Poland – a state which at that time Lithuania had no diplomatic relations with due to the dispute over Vilnius (then under Polish control and known internationally as Wilno) – but was freed after a month and a half following an appeal. However, he was barred from political office and didn’t return to public life until 1937. Petrulis became one of the first victims of the NKVD in Lithuania – in July 1940, following the Soviet occupation, he was imprisoned in Kaunas, then sent to Komi in the far north of Russia the following year, where he was shot.

Kazimieras Jasėnas was a Catholic priest and spiritual leader, and the author of six monographs. Born near Kaunas in Lithuania in 1867, Jasėnas completed his intermediate education in Jelgava, before attending Kaunas seminary.

For six years, he was a priest in Tukums in western Latvia, then in Brunava in the south of the country – in both parishes a church was constructed during his time there. In 1902, he returned to Jelgava, where under his supervision, a Catholic church was built, completed in 1906. In 1944, during the battles that took place in Jelgava, he saw the church burn down before his eyes, along with his library, which he had decided to bestow to Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas.

Although Jasėnas became close to the Latvian people, he never cut his ties with Lithuania. Jasėnas died in 1950 in the Latvian city of Liepāja.

The exhibition will be available to view at Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania in Vilnius from 1st to 21st June. More information here.

This text adapted from the booklet “The Creators of Independent States – Lithuania and Latvia – Mitau Gymnasium”. With thanks to Šiauliai Aušros Museum and Jelgava History and Art Museum for their help.

Header image – a postcard of Mitau Gymnasium [credit: Jelgava History and Art Museum]

© Deep Baltic 2017. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.