The Estonian director Terje Toomistu, who has recently completed a documentary about the hippie movement in the Soviet Union, writes about drug culture behind the Iron Curtain.

Throughout history, people have searched for ways to induce altered states of consciousness and thus to expand their perception of the world and its meaning. The Soviet Union might have appeared like a strict universe, anything but a place for sensuous tripping, but there, just like all over the world, there were seekers who couldn’t have been less concerned by the restrictions and commands of their time.

In this sense, Western hippies were not so very different from their mirror image on this side of the Iron Curtain — they were tripping there, and people were tripping here too. It’s just that “sex, drugs & rock’n’roll” acquired a much more existential dimension in the Soviet countries. A hippie slang expression can perhaps roughly illustrate it: “Лайф v кайф” or “Life on a High”.

While making a documentary about hippie culture in the Soviet times, I haven’t been able to overlook the politics of ecstasy and its related practices and folklore [1]. The following text summarises everything I can remember from the narcotic aspect of my research in the course of the film-making saga. But attention, attention – do not try this at home!

High

The Soviet Union dictated in very narrow terms to the public about what ways of being and feeling were allowed, and which were forbidden, to be met with reprimands or even punishment. The purpose of its propaganda was to shape a specific homo sovieticus, who would build the pillars of communism and march soberly towards the far-off, opalescent socialist utopia. Johnny B. Isotamm, a poet who emerged from the Tartu scene of the end of the 1960s, commented: “you were not reprimanded by far at all if you walked down the street in cotton pants or felt boots. These were the clothes of an honest working man. But if you showed up in flowery pants, you were almost a criminal”.

The norm was clear and rigid. Long hair, samizdats with religious content or strange bodily practices were a clear warning sign.

The air was strongly vibrating from the exciting wave of rock music that had absorbed here through the Iron Curtain and by the knowledge that young people in the “free world” were tripping in the enchantment of make-love-not-war. Soundscapes of guitar effects created a feeling of ecstasy, which the power puppeteers of course treated as a sign of wildness and undesirable influence from the decadent West.

The desire to experience something more than the empty promise given by Soviet power was not necessarily connected with the consumption of certain substances. The young people who were inspired by the knowledge of the global hippie movement and enjoyed good tunes had a radically different air about them. They believed more, they loved more, and their life was in the hands of a loose concept – “high”. Their life was formed by a longing for freedom and a joy in adventures, and was guided by spiritual practices. For sure, it was quite a colourful crowd of people, but if there was something that connected them, it was the fact they simply f e l t more.

LSD

Strangely, several articles were published in the media of Soviet Estonia at the end of the 1960s, describing the demise of the Western youth due to the influence of a horrible new drug. “LSD – a Door to Insanity or Paradise?” was a headline in the newspaper Edasi in the year 1968.

Although in these articles the use of drugs was deemed evidence of the failure of capitalist society, it obviously made adventurous young people here raise their eyebrows. The explosion of inspiration that emerged from the era reached many fronts. Music, graphic art, animation, and other arts got their fair share of it. But there were those who started to experiment with the available means right away.

It should be noted that LSD was an extremely rare substance in the Soviet Union. What is paradoxical is the fact that LSD was produced as medication, completely legally and with the support of the Communist government of a neighbouring country. The substance was available to a small circle of professionals, who used it for experiments or therapy. Back then, the public knew nothing about psychedelics.

Psychiatrist Stanislaf Grof, dubbed “the Godfather of LSD”, entered into an exchange programme between universities and went from Prague to Leningrad in 1964. He brought 300 ampoules of acid with him. Grof recalled that they had a séance every day for a month [2]. This must surely have had a revolutionary effect, and not in a scientific sense. It is said that the whole intellectual environment of the university changed cardinally after Grof’s visit. All at once, people started to take an interest in Zen Buddhism, yoga and Hermann Hesse.

Cannabis was the most widespread psychoactive substance. Legend has it that it was no problem to light up a sweet joint in front of Café Moskva [in Tallinn], because no one at that time knew exactly what this strange-smelling tobacco really was.

Over the years, a network developed among Soviet hippies, which the Russian-speaking population called Sistema (“the System”). Cannabis was spread through the channels of this network for a long time. If you ask a lifelong hippie where he got cannabis back then, the answer will be “from friends”.

In different socialist countries, different slang words were used for cannabis. The most common ones were plaan and anashá, but words like dryan, trava, smalá, and pahhol were also used, which could be translated as “crumbs”, “grass”, “puff”, etc. A joint — or kazyak – was not rolled, it was “beaten full”. This derived from a common method of stuffing the legendary Belamorkanal cigarettes: beating them full was an art in itself. A particularly awesome level was reached by blowing, which means that a cigarette was put into the mouth backwards and the smoke was blown towards the other person, who inhaled it at the same time.

Cannabis grew in large fields in the vast spaces of Ukraine, Central Asia and the Caucasus. The fields were meant for growing industrial cannabis; however, extremely wild fields flourished as well. In Central Asia, even up to the end of the 1960s, smoking cannabis was as public and as natural as bowing down to Allah. These habits were suppressed as a result of Khrushchev’s reforms and the increased interest from urban youth. But it was not possible to pluck up the personal patch fields of every poppa, and they had no success in preventing tea rituals with water pipes. It was no longer possible to buy cannabis publicly in a market, but it could be purchased under the counter. Even then, authorities noticed the commercial aspect instead of its intention.

Nevertheless, despite obstacles, travellers and dealers would bring cannabis to Soviet cities from the fields of faraway lands. Knocking on the cutter of a combine harvester which had been working in a field was enough to get a bucketful of hashish on your lap. But there was a sexier way to get the stuff – sending a couple of naked girls into a field. After they had run through the plants, pollen could be collected from their sweaty bodies. Horses could also be ridden through a field. However, the most common method was to take the top of a plant between your palms and rub it. Doing this for about twenty minutes next to a field would result in as much as a week’s worth of weed. Usually, the stuff was sold by matchboxes, which were known by the slang name korablik (boat). The next unit up was a tea glass (and the next one would be a bucket probably).

If the militia detained a long-haired guy in the street – and this did happen – it was never known if his fate would be worse because of the handful of cannabis in one pocket or the book by Solzhenitsyn in the other. When an apartment community in St. Petersburg was raided unexpectedly, there was a bucketful of grass on the kitchen table, but the KGB men thought nothing of it. They rummaged through the bookshelves instead – if only they could find that forbidden literature!

It’s said it was pretty common in Central Asia for a mother to give a spoonful of poppy tea to a coughing kid – it would heal their lungs. In the second half of the 1970s, poppy tea and opium started to spread among young people in the cities. Vladimir Wiedemann, in his book “The School of Magicians”, describes [3] how all at once poppy blossoms disappeared from all the Communist monuments, simultaneously with the popularising of poppy tea.

Opium was smoked, but tea was brewed from it as well. Some people cut notches in a poppy capsule and left it in the sun to ooze onto a cheesecloth. The substance could be boiled out from the cheesecloth later on. More devoted practicians distilled and messed with poppy in other ways, until a strong liquid was formed which could be injected into their veins. This is quite a sensitive topic among my informants. Certain people feel it’s best to leave the room when drugs are being discussed. As the quantity of opiates in poppy seeds fluctuates, it is difficult to fix the correct dose. For this reason, many people have lost friends on this journey.

Astmatol and Sopals

Over time, chemical substances started to spread among certain crowds. Pharmaceutical hits were Seduxen, Dimedrol, and Cyclodol. The first two were strong sedatives, which supposedly cause a deep stoned effect. The last one had a hallucinogenic effect. I have heard about an experience where the world turned into a mycelium where tiny creatures bustled about.

One of the strangest solutions the Soviet youth came up with was boiling tea from Astmatol cigarettes, which were intended for asthmatics. Smoking the cigarettes was meant to relax the respiratory muscles in case of an asthma attack. But this magical smoke contained different psychoactive components, such as soursop and black henbane. How on earth did someone discover the fact that when you boil a whole pack of Astmatol cigarettes like tea, the result is a quite hallucinogenic brew? You just sip your tea and notice how, little by little, the world around you is changing.

Some odd, audacious experimentalists would inhale a detergent by the name of Sopals, which was produced in Latvia. Its primary active ingredient was ether. You can read about collective Sopals rituals and amazing adventures in the Estonian occult underground in Wiedemann’s memoirs. Usually, the substance was sprayed on a handkerchief. In winter, psychonauts would dab their scarves with it – why not sniff while you walk?

Drug addiction

They were not hippies per se, but in the Soviet times some people were devoured by drug addiction. For instance, at one point an ephedrine-based fluid was going around, which was colloquially called tšef. A hippie of the time described his experience to me. His friend worked as a night-watchman at the Ministry of Industry. Lots of free spirits had this kind of job – it’s really nice to read a book all night long and have a puff.

He visited this friend once to drink some tea, but soon enough a few young Russian guys from Kopli [a rough inner-city district of Tallinn] turned up as well. They took out their syringes and the fun began. The purpose was to reach an extraordinarily high state, if the substance hits hard. This was called “the coming” – prihod in Russian. He just kept on peacefully drinking his tea; he could not have foreseen that one of the most horrendous nights of his life was to follow.

The room gradually became filled with moans of pleasure, signifying the awaited “coming”. One guy messed with the syringes for as long as six hours – six hours in a row! Twitching his body in every possible way, he kept looking for a vein, on his hands, feet, and neck. With a small groan of pain, he would prick the syringe into his body and wait expectantly – but to no avail.

That night he did not get to a vein, and his hands and feet were thoroughly pricked and hurt from his attempts to inject. Before long, the day dawned and they had to leave before the next shift.

[1] The author would like to thank all the people who have contributed to this article by sharing their memories.

[2] Interview with Stanislav Grof, Mill Valley, California, 01/04/2014.

[3] Wiedemann, Vladimir. School for Magicians. Estonian Occult Underground 1970–1980. Tartu: Hotpress Kirjastus, 2008.

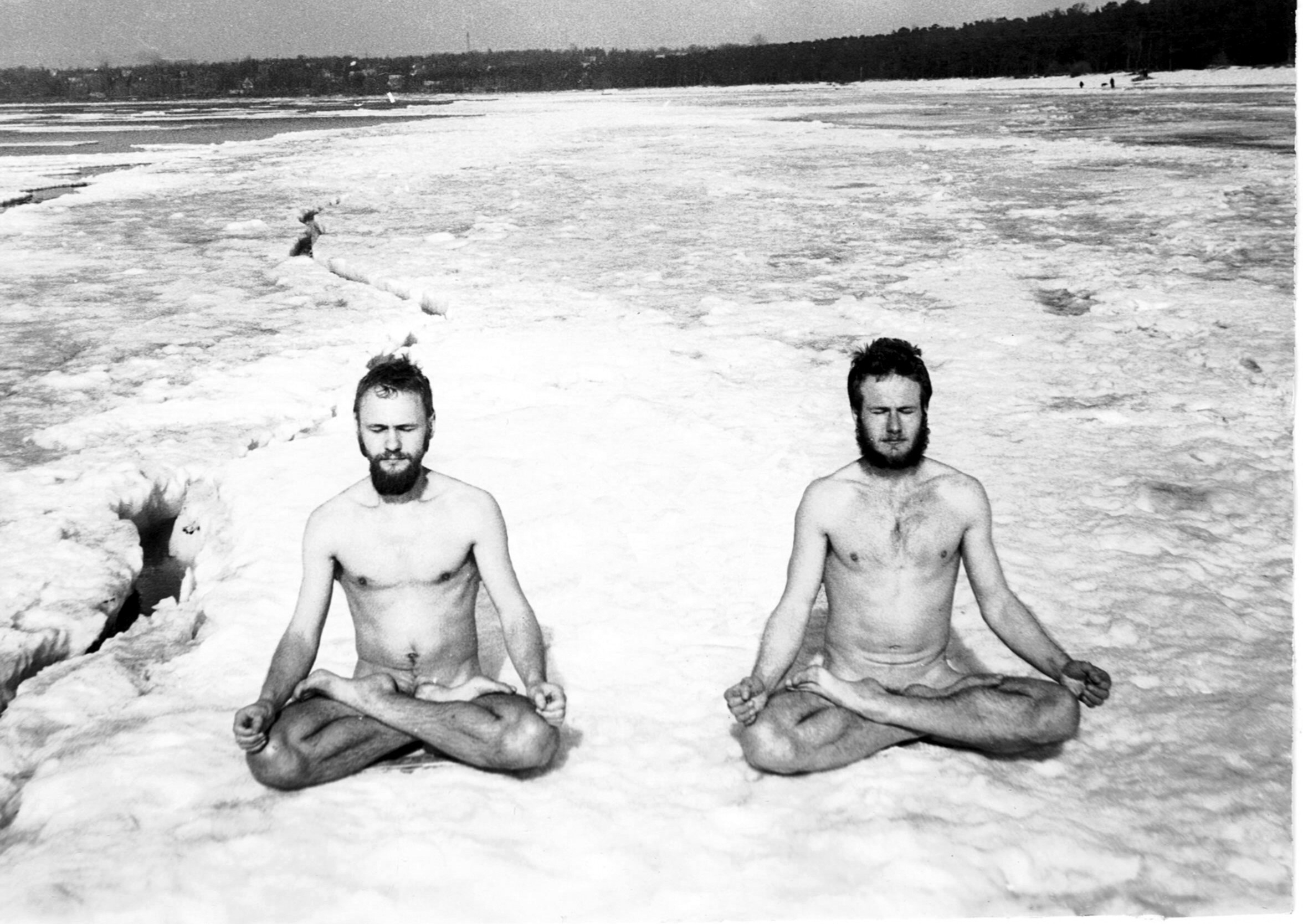

Header image: Vladimir Wiedemann and Dmitri Petrjakov meditating on the snow in Tallinn in 1982 [Courtesy of Dmitri Petrjakov]

All photos – Poja, unless otherwise specified

Terje Toomistu (b. 1985) is an Estonian documentary filmmaker with a background in anthropology. Her work often draws from various cross-cultural processes, queer realities and cultural memory. She holds double MA degrees (cum laude) in Ethnology and in Communication Studies from the University of Tartu, where she is pursuing a PhD degree in anthropology. In 2013-2014, she was also a Fulbright fellow at UC Berkeley, U.S.A. Currently she is a visiting researcher at the University of Amsterdam. She co-curated a multimedia exhibition about Soviet hippies, which has been exhibited in museums and galleries internationally.

Soviet Hippies is set to have its international premiere in competition at the upcoming São Paulo International Film Festival in Brazil this month. For more information, visit the film’s official website or Facebook page.

Terje Toomistu is currently raising funds to issue the best tracks from the soundtrack of Soviet Hippies – all taken from the Soviet underground – as a coloured vinyl record, illustrated with archive photos. You can support the project at Indiegogo here.

© Deep Baltic 2017. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.