It’s no surprise that cultures that have suffered for long periods under oppression are particularly well known for their fairytales, as these tales are widely recognized as our metaphoric way of addressing and resolving anxiety. Both the Irish and the Balts are fine examples of this phenomena, although there are many more such cultures throughout the world. The bugaboos that appear in fairytales confront basic human fears, but they also allow an outlet for speaking about life’s threats without giving them their true names. And although we usually think of fairytales as a genre designed for children, the novel could, if we are being honest with ourselves, be viewed as a fairytale for adults, allowing us to place our dreams and fears within a context that assigns some kind of meaning or order to a chaotic world.

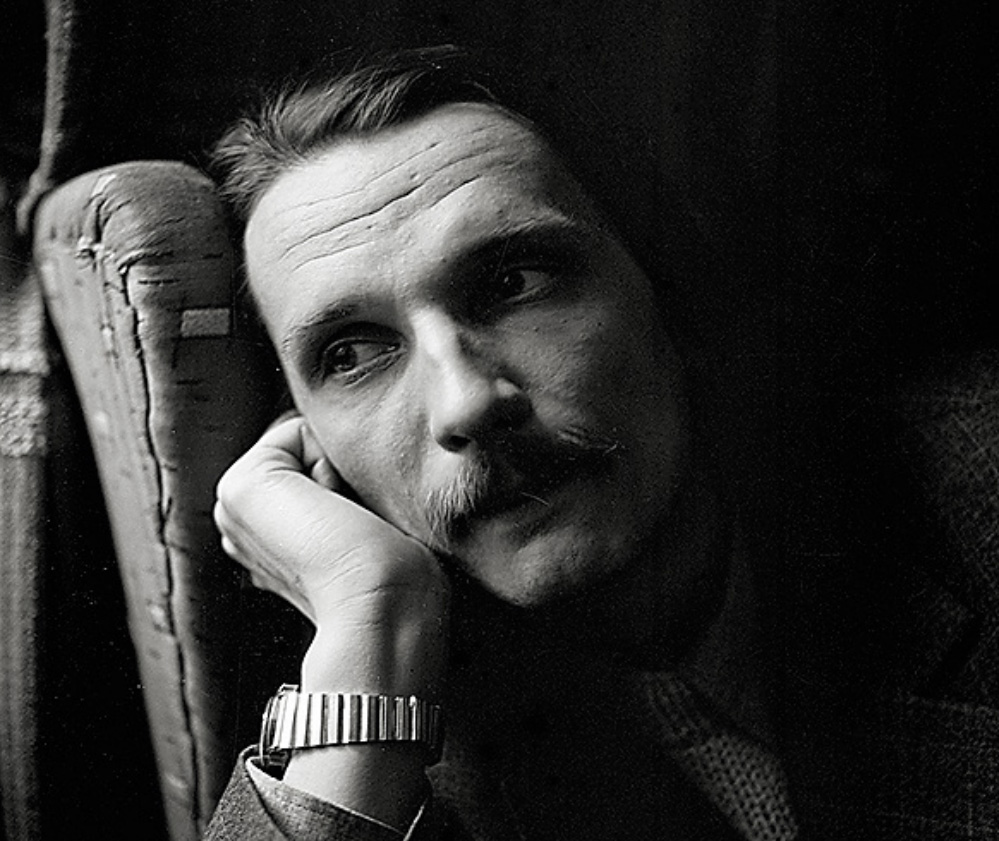

This is one way to look at the work of the Lithuanian writer Ričardas Gavelis—as a particularly fine twenty-first century example of the Lithuanian propensity for fairytales. His grotesqueries seem born of the deep gloom of those dark forests and those mysterious northern bogs, springing forth fully formed, much like the grotesqueries of Lithuanian folk carvings. But it must go further than that, and penetrate the very soil beneath the city streets: Gavelis spent almost all his life treading the paving stones of Vilnius, and almost all of his works are set there. Certainly Lithuania’s bloody history forms a vivid backdrop, but, just as a fairytale does, Gavelis’s novels always openly deal with entirely universal traits: fear and disgust, envy and greed, good and evil. And power.

From the Vilnius Basilisk lurking in the back corners, to letters written from beyond the grave, the fantastic is at the base of Gavelis’s art. And yet, instead of the novels being set inside some entirely imaginary Game of Thrones world, it is the city of Vilnius that performs the role of the shape-shifter, from the dank, drab, crumbling Soviet skies of his early works to the slick modern European capital it was on its way to becoming when the author died in 2002. Part of how Gavelis makes his fantastic elements so effectively frightening is to seat them in perfectly ordinary situations: a man walking down the street looks up to see some pigeons frozen mid-air, and discovers time has stopped. A couple is celebrating an anniversary when the paintings on the wall begin moving. It’s these experiences of descending into a character’s nightmarish perceptions, and aspects like the in-you-face metaphoric role that parents play in his works (see: the Wicked Stepmother), that penetrate our deep-seated psychological roots and account for some of the disturbing effects his novels have upon us hapless readers.

But that by no means is the only way Gavelis horrifies us. Gavelis is a writer who is not just thought-provoking; he can be provoking in all respects, and in particular to Lithuania and Lithuanians.1 Among the many writers Gavelis has been compared to, it’s surprising no one in the West has compared him to our Bad Boy Henry Miller, whom he resembles in some other respects as well. Gavelis’s characters can say the most offensive things, but they are so unfortunately true to life it makes your teeth ache. Questionable moral decisions abound, just as they do in real life, always and everywhere, and not just in Lithuania. Politicians (and ordinary people as well) lie and cheat, and destroy one another. Men and women make use of one another in the most shameless ways. And we’re constantly confronted with the more unpleasant aspects of human physicality. Lithuanians take offense at the use of their name, but their name is legion, and, with a nod to Pogo the Possum—we have met the enemy and he is us, right?

It sounds grim. But just at that point when you think you just can’t take any more of it, you’re suddenly hit over the head with some adventure or a description so absurd, so over-the-top, that it has you laughing out loud. Suddenly we see the storyteller is pulling our leg—don’t all the children giggle when the wolf tries to speak in Grandma’s voice? Like the funeral of a former torturer where the bloating corpse won’t stay in the coffin, or a Trump figure forced to dance the kazachok; rabbits named “Lenin” or “Stalin” so it would be easier to kill them, or the single frog whose croaking fills the Universe.

The reader is forced to ride on a roller-coaster, and inevitably, not every reader stays on; we all have different limits to how bleak, or how insane, or gross, or insulting we can take it. Some find the feeling of their consciousness being forced into uncomfortable places manipulative, or simply downright unpleasant. The remarkable thing is how Gavelis manages to wreak this much havoc, and then make us laugh, too.

The Lithuanians themselves have always been ambivalent about Gavelis. It was rough enough when he pulled the pants down on—well, everybody and everything, really, in his wildly best-selling 1989 taboo-breaking novel of the Brezhnev era, Vilnius Poker (first published in English translation by Open Letter in 2009). Many were happy to throw the novel into the “anti-Soviet” bucket, as that made the book more acceptable to the mainstream, although any careful reader would certainly see there was far more meat, both figurative and literal, in it. The critic Violeta Kelertas’s proposal to analyze Vilnius Poker in the light of post-colonial theory has certainly been fruitful. Allan Cameron, in his thoughtful introduction to Gavelis’s second novel, Jaunas žmogaus memuarai (translated into English as Memoirs of a Life Cut Short, Vagabond Voices, 2018), acknowledges the anti-Soviet aspects, but also expands on Gavelis’s more universal themes. “Power is the problem,” Cameron states, and indeed Gavelis never saw power and its attendant corruption as a merely local phenomena.

The Lithuanian reaction to the novel was in part driven by Lithuania’s history and the development of Lithuanian literature. The first printed work in Lithuanian arose from the Reformation’s interest in vernacular languages, but further developments were quashed by neighboring languages with more prestige—in Prussia, by German, and in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, by Polish—not to return in earnest until the rise of nationalism in the nineteenth century. During that period, Lithuania was ruled by Russia, and in reaction to the 1863 uprising in the territory of the former Commonwealth, and in an attempt to reduce Poland’s influence, Russia decreed that Lithuanian books were to be printed only in the Cyrillic alphabet. This decree gave rise to the phenomena known as the knygnešys, the smuggler of books and newspapers printed in the Latin alphabet. During the fleeting period of Lithuania’s independence between the world wars, vernacular literature was finally able to flourish freely before it was once again quashed by the Soviet takeover in 1945. Forced to abide by the imposed standards of Soviet Realism, prose withered, while poetry, with the Aesopian nature of its language allowing the evasion of censorship, flourished. Given this background, Gavelis’s sometimes scatological prose, with its frank sexual descriptions and elements of the fantastic, was everything Soviet Realism was not.

Gavelis’s next novel, Vilniaus džiazas (Vilnius jazz, 1993), a multiple bildungsroman of both men and women again mixed with fantastical elements—and a stint in the Soviet Army—is especially popular among younger Lithuanians, and is by far the most optimistic and fantastic of his works. During this period Gavelis seemed to rely a great deal on notes he had made earlier, during a time he couldn’t be published, as literary scholar Jūratė Čerškūtė has discovered from examining his his archives. His subsequent books, frequently dealing with post-Soviet Lithuania and the machinations of power that ensued in the clash of East and West, of capitalism and the remains of communism, are less well-read. It’s tempting to suspect that everyone in Lithuania was having enough trouble with lessons in reality as it was, in that first decade after the heady days of independence, without having it stuffed in their faces. But it would be difficult to imagine how his 1999 book with the title Septini savižudybes būdai (Seven Means of Suicide) could possibly gain popularity in a country known to have the highest suicide rate in Europe, even if the book is actually more a purely Gavelian treatise on the art of writing. Gavelis’s last work, and his third to be translated into English, Sun-Tzu’s Life in the Holy City of Vilnius (2019), originally published in 2002 as Sun-Tzu gyvenimas šventame Vilniaus mieste, most certainly falls into the category of the unloved in Lithuania; how could people love a story that painted a Lithuania whose alternate universe is a fantasy of corrupt Eastern European government? It seems the book was actually written for a different time and a different audience, despite the chains (or charms) of an obscure language not English.

When it was written, the West had already opened up, and was there for the exploring. But in the meantime, the influence of the East, its hypocrisy and corruption, continued to creep ever westwards, as the United States, and now Europe, have learned to their regret. Gavelis’s fascination with evil and power may not have ended with the Soviet era, but in Sun-Tzu it is blown up to an extent that would once have seemed hilariously fantastic, but now seems an eerie foreshadowing of recent history in both Europe and the United States. One wonders, seriously—did Gavelis have clairvoyant powers? After reading his straight-faced description of a government minister who “resembled a giant plastic bag filled with sticky starch paste,” who “was even expertly painted the color of a human body… A tall, sturdy man with clumsy paws and giant, weighty buttocks,” (191) one wonders where Gavelis could have met Trump twenty years earlier, or is Trump merely a trope himself?

The novel’s voice is that of a man who is utterly obsessed with recognition—but who gives his name only as the Sun-Tzu of Vilnius. The book purports to be his autobiography. From the opening page we are treated to the mind-boggling hubris of an individual who can look at a crumbling Soviet-era housing block and state, “I’m not at all afraid: I can hold those collapsing buildings in a vertical position by the strength of my will alone.” That gross exaggerations make up large portions of this fable, in light of our own contemporary experience with political leaders, must seem to some now to have a terrifyingly familiar ring. Sun-Tzu’s rise to power occurs through a combination of his stepfather’s collection of KGB files and a campaign utilizing a gruesome totem: the head of his father, decapitated by Soviet authorities for attempting to form an underground independence group. It is a horrifying reminder of where ultra-patriotism can take us.

The narrator’s life story culminates in his retreat from the pinnacle of power in Lithuania’s government to an underground bunker in Vilnius, where he launches attacks on what he sees as human “cockles”, the weeds from Mark’s parable, although it is never clear that he isn’t one himself. The novel is bracketed by graphic descriptions of what could be episodes from an action film, in which the protagonist confronts a military unit sent to dispatch him. In this peculiar Sun-Tzu, we have an archetype of an Osama bin Laden, whose war is based on ideological grounds, albeit questionable ones. Unless, of course, we gaze deeper, and recognize that all of it, then, now, and everywhere, is based on a struggle for a place in the world.

This book purports to be an autobiography, but its ending puts the lie to that notion. I say it’s a fairytale—in part because of the metaphoric quality Gavelis imbeds in his works. Parents, for example, have always been a powerful part of Gavelis’s arsenal, and in Sun-Tzu we are treated to three of them (plus possibly the protagonist’s friend Apples Petriukas in a previous incarnation). Strange and deformed as all parents are in our eyes, these are irrationally all-powerful, and so over the top that you’re tempted to see them as a sendup of Freud. One is a physicist who deconstructs the Universe, another becomes the Angel of Death, and then there’s the stepfather, who, in one of several nods to Lewis Carroll, resembles a caterpillar, with brooches pinned all over his body.

Voyeurism is another tool in Gavelis’s kit, one that simultaneously fascinates and horrifies us. It plays as much a part in Sun-Tzu’s Life as it did in Vilnius Poker. In this fairytale world, the narrator with his First Father can travel invisibly throughout Vilnius and stand in the corner of an apartment, observing a family living its life, or perch on a fire escape, watching a dying woman in her kitchen. Again, Gavelis seems to have divined the world as we know it now, twenty years later, where cameras observe us everywhere, even within our own homes, and are only growing more ubiquitous.

Lithuania’s history has provided an inexhaustible source of material for the writer, and the story of how the Jewish population remaining after the Holocaust completely disappeared from Vilnius, here told metaphorically as a Jewish girl withers and dies from the protagonist’s compulsive gaze, is but one example. But that metaphoric quality also mystifies us. What exactly did happen to Sara—was she merely a victim of anorexia? The WWII invalids on carts rattling through the streets of Vilnius reflect the reality of postwar Lithuania—including the acts of retribution sometimes taken during the partisan war that tormented Lithuania in the decade after the war officially ended—but they are also a metaphoric reflection on the state of this post-post-everything society, as is the recurrent (and painfully funny) theme of prostheses.

As always with Gavelis, characters and motifs from previous novels or stories reappear, and if you have read his previous works, some are quite welcome—they’re characters you’ve met before, and wouldn’t mind spending some more time with. For example, Levas Kovarskis, the surgeon observed from four different viewpoints in Vilnius Poker, here returns to the stage for a fifth, furiously dissecting corpses as fast as Sun-Tzu brings them, this time in search of that second brain of the gut. Apples Petriukas himself had a much earlier appearance in a short story.

With Gavelis’s powers of foreseeing the future, perhaps we should not be surprised at the cataclysmic ending, and the irony that the writer himself died soon after turning in the manuscript, alone in his apartment. I doubt he would have wanted it any other way. Since then, some of his works have simply refused to go away, going through multiple editions and translations into many languages. As Richard Beck has observed, “Your whole life is involved in everything you write, and that involvement will make itself felt on the page one way or another, whether you like it or not.” It makes one wonder just exactly what Gavelis’s life was like, that he could write such bleak and funny fairytales, but it is obvious that he came to “accept the violence of his own mind”, and most certainly I can only hope that the world, as well as Lithuania, comes to appreciate all of Gavelis’s work some day.

Sun-Tzu’s Life in the Holy City of Vilnius by Ričardas Gavelis, translated by Elizabeth Novickas (Pica Pica Press, 2019). 274 pages. ISBN 978-0996630436.

Memoirs of a Life Cut Short by Ričardas Gavelis, translated by Jayde Will (Vagabond Voices, 2018). 260 pages. ISBN 978-1908251817.

Vilnius Poker by Ričardas Gavelis, translated by Elizabeth Novickas (Pica Pica Press, 2016). 438 pages. ISBN 978-0996630429.

1. See Almantas Samalavičius, “A Conversation with Ričardas Gavelis,” Lituanus, Winter 2019, Vol. 65:1.

Elizabeth Novickas is a graduate of the University of Illinois with a B.A. in Rhetoric from the Urbana campus and a M.A. in Lithuanian Language and Literature from the Chicago campus. She has worked previously as a bookbinder and fine printer in Urbana, Illinois; as a newspaper designer and cartographer in Springfield, Illinois; and as system administrator for the editorial department at the Chicago Sun-Times. She was the recipient of a 2011 translation fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and in the same year won the St. Jerome Prize from the Association of Lithuanian Literary Translators for her translations of Vilnius Poker (Open Letter, 2009) and Whitehorn’s Windmill (CEU Press, 2010).

Header image – credit: Rijksmuseum

© Deep Baltic 2023. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.