by James White

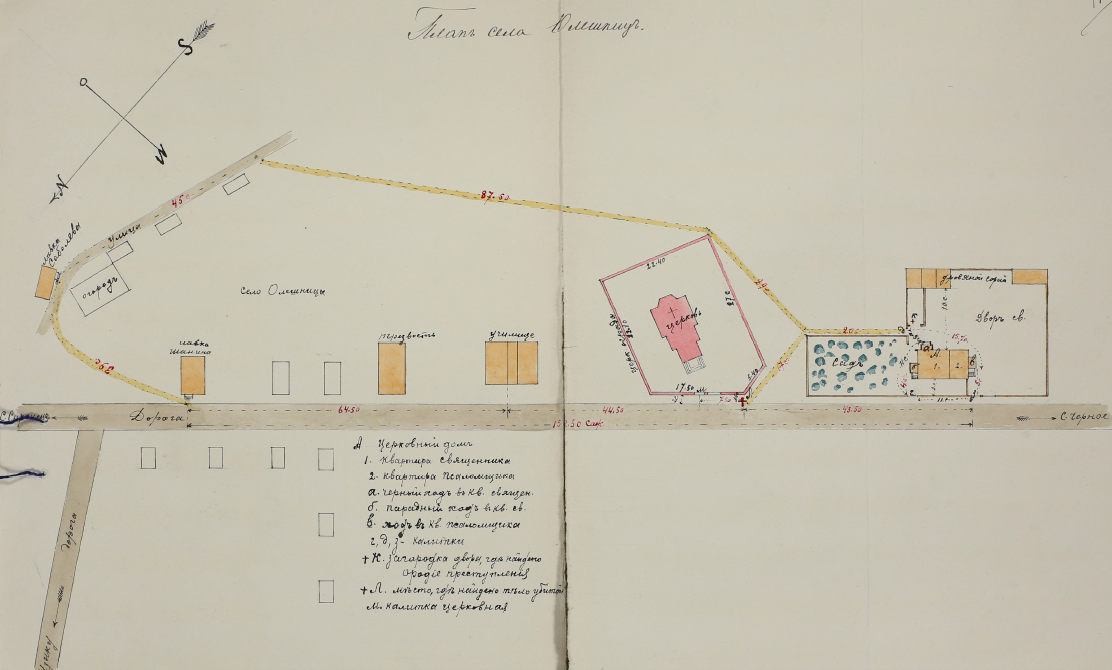

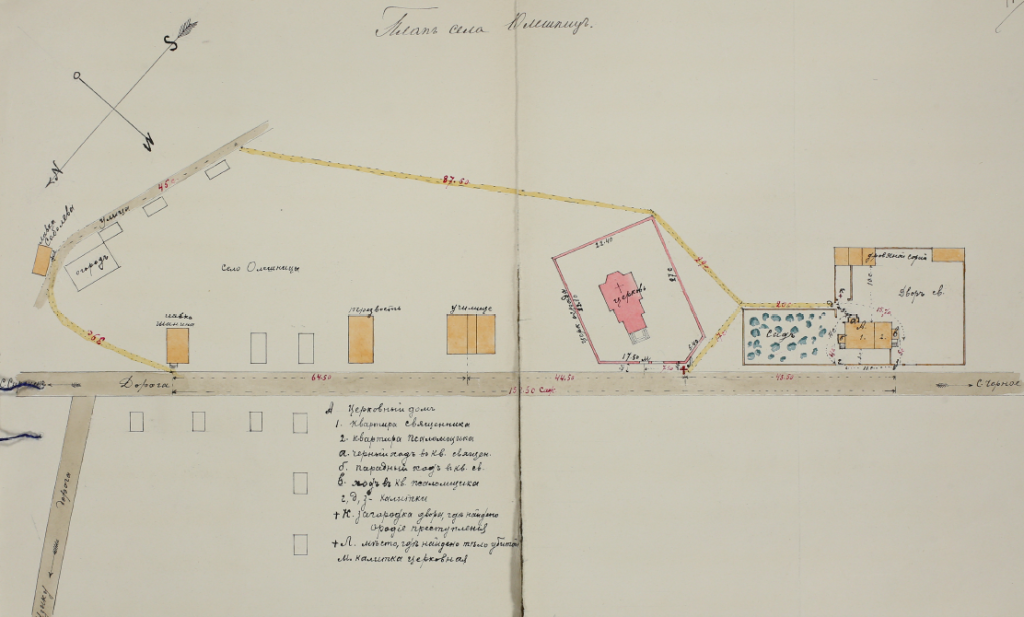

“On the northern coast of Lake Peipus, lost amidst swamps and forests, amidst a non-Russian and non-Orthodox population, distant from large, populated places and good roads is the Orthodox Russian parish of Alajõe. Its residents are not rich because almost the only source of food, fish caught in the lake, has become more and more meagre in recent years.”1 This was how an appeal for charity introduced the public of the Russian Empire to the remote eastern Estonian locale of Alajõe (Oleshnitsa) and its 1,000 or so Orthodox parishioners in 1912. Unsurprisingly, though, the call for donations glossed over the terrible events that had occurred just a few months early in the sleepy, bog-straddled village: the brutal murder of the priest’s wife Zinaida Troitskaia and the scandalous secrets the subsequent criminal investigation uncovered about the local Russian Orthodox clergy. In this brief article, we chart the circumstances of this crime and the surprising details it reveals both about this remote hamlet and the hidden lives of the rural Orthodox priesthood at the end of Estonian history’s imperial epoch.

Discovery2

At around 19:30 on 1 December,3 the Orthodox sacristan Ivan Boltov grasped his walking stick (a solid oak pole topped with an iron orb) from by the door of his small apartment, making ready to depart. He had spent the last hour gossiping with his wife Anna and the local teacher Mariia Domina about the events of the day; now he intended to brave the cold, dark winter night to visit the local tavern, where he could hear news of the market held in Vasknarva, a few miles to the east.

Within mere minutes, however, Boltov was back: his wife had not even had time to lock the door after him. Visibly shaken, he relayed the news that he had seen a body lying by the church walls. The small party first went to the nearby parochial house, knocking on the door of the servant’s quarters for the priest’s maid Anna Tverskaia. Together, Boltov and the three women cautiously approached the dark shape strewn on the white snow, the light of the sacristan’s lantern casting the scene into vivid relief. Although the face was covered by a grey-blue woollen scarf, the group recognised the victim by her clothing: it was the priest’s wife, Zinaida Troitskaia. Not knowing whether she still lived, they split up to get help: Boltov and Domina retreated to the school to fetch the church’s junior sacristan Semen Karpin, while Boltova and Tverskaia rushed to the shop where Father Aleksandr Troitskii was known to have spent the past few hours playing backgammon. The two women shouted out as they ran, rousing villagers from the warmth of their stoves. Karpin was the first to arrive back on the scene: clasping Zinaida’s ungloved right hand, he found it cold to the touch. He then placed a palm on her chest, hoping to feel some warmth. Trying to raise her head, Karpin felt a wet, sticky sensation. Pulling his hand back, he saw blood dripping from his fingers. At that moment, he and those around him knew that Zinaida was dead.

Karpin was dispatched to the Iisaku manor house to procure police assistance, which arrived on the morning of 2 December in the form of junior official Ishchenko. Zinaida’s corpse had been moved into the parochial house but had otherwise not been tampered with: the left hand still clutched the glove that had once covered the right. After a brief inspection of the body, Ishchenko examined the murder scene: a pool of blood marked the spot where Zinaida had lain. There he discovered a trail of tracks left by winter boots, leading to the well of the parish school. After a few initial interviews to establish how the corpse had been found, the officer had done his duty: it was time to hand the matter over to his senior and a police doctor.

The autopsy records with clinical precision the mess that had been made of Zinaida Troitskaia. Much of the right-hand side of the skull had been shattered into small pieces: the victim’s blonde hair was matted with blood, bone, and brain matter. Indeed, the doctor noted, had it not been for the headscarf, much of the brain would have leaked out when the body was moved. He concluded that the cause of death was two blows to the head with a heavy object; it was likely the second proved fatal, as it had been responsible for disintegrating the brain.

Meanwhile, senior officer von Rengarten began his detailed investigation. He first set about poking around the parochial house, especially its yard. His eye was drawn to a birch log, standing suspiciously separate from its brethren in the firewood pile. Taking out his penknife, he scraped off the snow to find part of the bark stained red. Equally, strands of blonde hair and tufts of grey-blue fluff (the same colour and material as Zinaida’s headscarf) caught the detective’s attention. Standing up, von Rengarten now noticed he was being observed; a quick enquiry revealed that the onlooker was Ivan Boltov. Suspicion piqued, the officer started to conduct detailed interviews with the clergy and residents, seeking to find out what precisely had been going on in the village of Alajõe.

1 December

At approximately 8 o’clock on the morning of 1 December, Zinaida Troitskaia began to upbraid her husband, Father Aleksandr, in the ground-floor living room of the parochial house. On the previous day, she had seen Ivan Boltov peeking at her through the window: her husband, she believed, had asked the sacristan to watch her. Troitskii flatly denied this and summoned Boltov to give an account of his behaviour. Initially denying the charges, Boltov rapidly cracked when Zinaida persisted, confessing that he had indeed been watching her. Boltov had spied in the expectation that his 26-year-old colleague Semen Karpin would pay private visits to the 39-year-old Zinaida while her husband was absent: as Boltov elucidated, Zinaida was in the habit of calling Karpin by the pet name “Senichka” and spending many hours in his company, even without a fire. Zinaida did not refute this, declaring that she and Karpin were in love.

Zinaida then went onto the attack: Boltov, she remonstrated, had scandalous photographs and letters that had once belonged to Father Aleksandr, which he repeatedly showed to others in the village. Boltov not only confirmed that he had these compromising items, but also that he possessed them with the intent of blackmailing the priest should their relationship sour in the future. He had bought them some years earlier from an Estonian repairman, who had stolen them while renovating the parochial house. It later emerged that Boltov had also been given one of the photos by Karpin’s predecessor, the sacristan Nikolai Laskeev: he, too, had been Zinaida’s lover, and it was she who had given him the picture. Witness testimony and the police evidence report confirm all this. Of the photographs seized from Boltov, nine showed a naked woman in various poses, three displayed another disrobed woman sitting or lying on a bed, and two depicted Father Aleksandr and one of these women lying undressed on a bed. Most disturbingly, the final image was of a child’s flaccid member. The letters in question were all addressed to “Shura” (Aleksandra) and “Vera”, presumably the two women in the pictures.4 Father Aleksandr was not only unfaithful, but also indulged in amateur erotic photography.

At this point in the candid meeting between priest, wife, and sacristan, Zinaida delivered a final verbal blow against Boltov: he was angry with her because of “her refusal to satisfy the shameful propositions with which he turned to her.”5 Calm until now, Boltov boiled over. Spluttering expletives at Zinaida, he stormed out, returning home to spend the next few hours fuming at his wife. Father Aleksandr placidly called for junior sacristan Karpin in order to confront him with the cuckoldry. Karpin denied everything, so the priest got his maid (and Karpin’s cousin) Anna Tverskaia to retell what she knew. She said Karpin had indeed visited Zinaida in the parochial house every evening from 14 to 20 November, leaving only early in the morning. Furthermore, the illicit couple’s tracks had been found going from the priest’s banya to the icy shores of Lake Peipus, suggesting the two had conducted their romance in the sauna. Karpin now confessed to everything.

Father Aleksandr remained stoic, even taking tea with his wife at around 4 o’clock. He then left the house for a couple of hours, returning at 6 to find the front door locked. Tverskaia revealed that Zinaida had gone to Karpin, “whom she loves and intends to see without limitations.”6 With the same indifference he had shown throughout, the priest departed to while away an hour or two over some backgammon; this was where he was found when his spouse’s mangled body was discovered.

Interviews with various witnesses, including the Estonian priest Ioann Vevo and Father Aleksandr’s own brother, the petty bureaucrat Aleksei Troitskii, revealed the married couple’s unusual relationship: “Zinaida Troitskaia’s behaviour was entirely frivolous and rumours were going around about her many betrayals of her husband: moreover, the latter knew about this and was left fully indifferent, since in the course of many years he had not had marital relations with Zinaida Troitskaia and, in his words, ‘looked for satisfaction on the side’: in view of this, he was connected to his wife only through domestic interests and cared only about maintaining external propriety.”7 Indeed, Zinaida had taken as her lover not only Karpin and Laskeev, but also one of Father Aleksandr’s relatives, Fedor. The priest’s only noted response to all this was to jokingly refer to his wife’s infidelity when chatting with his brother (although Boltov also alleged that Troitskii had driven Zinaida and Fedor out into the snow when he caught them in a tryst in 1910).

Zinaida’s final movements were attested by several witnesses. Leaving just after her husband’s initial departure from the parochial house, she had gone to Karpin’s domicile, where the two had quarrelled about the embarrassing revelation of their affair. She then spent some time chatting to Mariia Domina before going to buy some sugary treats. At the trader’s, she once again encountered Karpin, with whom she made up. Her egress from the shop was the last time anyone saw her alive.

Trial

Having compiled this picture of events, von Rengarten swung into action. His suspicions had already been aroused when he saw Boltov observing his inspection of the bloodied birch log. They were only exacerbated when this key piece of evidence went missing on 2 December. Boltov’s intent to engage in blackmail, his anger with Zinaida during their confrontation, and his possession of another potential weapon in the form of his heavy oak staff only condemned him further. Apparently key was the testimony of Domina, who claimed that Boltov was “entirely hot-tempered and angry by nature, distinguished by harshness even in relation to his own children.”8 Although initially supporting Anna Boltova’s statement that Boltov had only been gone for a few minutes when the body was discovered, she admitted that the period might have been much longer, as she had been engrossed in conversation with Boltova and had not been paying mind to the length of Boltov’s absence. The priest’s brother Aleksei Troitskii also asserted that he had seen Boltov enter a tavern shortly after Zinaida was discovered: the frightfully pale sacristan had ordered vodka, explaining that he had gone to the banya and needed to cool off with a shot of stiff drink. Anna Boltova, while not denying that her husband had gone directly to the steam bath almost immediately after finding the corpse, argued that Boltov had done so because he felt ill. It was difficult to explain away this strange behaviour.

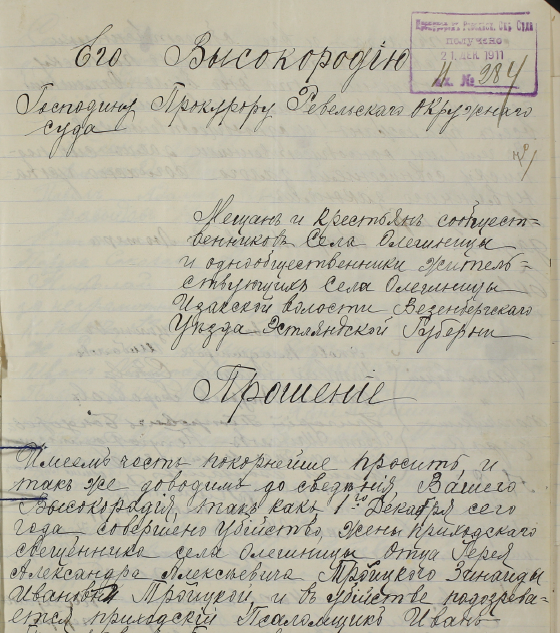

So, von Rengarten arrested Boltov and carted him off to the jail of Jõhvi, a railway town to the north. He was to sit there for several months, awaiting trial in the city of Narva. Something of the febrile atmosphere he left behind him in Alajõe can be gleamed from a panicked missive by Father Aleksandr: “[Boltov’s] wife, after his arrest, poured still more oil on the fire, strongly agitating many parishioners against me”. Consequently, 15 believers had sent a petition to the archbishop of Riga, demanding Troitskii’s removal from the parish: “did they actually describe my acts or [provide] damnable falsifications?”9 One man, Aleksei Abakov, had apparently been spreading the rumour that he had seen Troitskii fleeing the scene of the crime. The priest ends his letter with a plea for advice: should he abandon the parish or take his slanderers to court? In aggrieved self-pity, he complains that the 12 years he had spent in this secluded parish without creating trouble or becoming a drunk were being wasted.

At 11:15 on 31 May 1912, Boltov’s public trial in Narva began. The defendant had an uphill battle to fight: after all, he had already admitted to his quarrel with Zinaida and the possession of photos kept with the intention of blackmailing the priest. All he could claim, rather lamely, was that he and Father Aleksandr had enjoyed a good relationship over the 12 years the priest had spent in Alajõe. This was contradicted by several witnesses, who said Troitskii had only one enemy in the parish, and that this was Boltov. However, holes started to appear in the prosecution’s case. First, there was the lack of a murder weapon. The log found by von Rengarten had gone missing, and it had vanished before a chemical analysis on the red staining could confirm the presence of blood. Further, the police doctor argued that Boltov’s staff was not heavy enough to have inflicted the kind of devastating damage Zinaida’s skull had suffered. Second, the negative character assessment given by Domina was contradicted by positive appraisals from several prominent villagers: according to a petition (in ungrammatical and badly spelt Russian) submitted to the court, Boltov was “a god-fearing man and without reproachable behaviour, he has never insulted even the smallest child and is also not a drunk or some kind of dragon.”10

All of this swung things in Boltov’s favour: the jury delivered a unanimous “not guilty” verdict. Boltov was set free, and Zinaida’s killer was never found.

Can we, over a century in the future and using old police reports, come to a better conclusion? Father Aleksandr, it seems, enjoyed a rock-hard alibi, with numerous witnesses attesting to his whereabouts at the time of his wife’s murder; however unseemly the contents of his erotica collection, his attitude towards his wife’s unfaithfulness was one of apathy and even humour. The case against Boltov, a murky, distasteful character filled with anger towards Zinaida only hours before her death, looks strong. But the gaps poked by his lawyer in the prosecutor’s version of events are fair enough. Two witnesses, his wife and Mariia Domina, saw him reappear only minutes after leaving his home. Many parishioners defended his character publicly. However bizarre his sudden trip to the steam bath might appear, who can say how a person might act after finding the body of a relatively close acquaintance? And perhaps his watching the detective scrutinise the stained birch log was due to mere curiosity, and not the starting point of a plan to dispose of the murder weapon? Suspiciously and strangely absent from much of the investigation is Semen Karpin, the last person to talk to Zinaida. Maybe their argument over the revelation of the affair to Father Aleksandr had been worse than believed? Maybe he feared for the repercussions that the inevitable controversy would have on his young career in the Church, leading him to clumsily remove a potential source of trouble? Or was the entire matter a random act of violence, not unheard of in the under-policed darkness of the Russian Empire’s rural depths? The truth will never now come to light.

Aftermath

Although the scandal does not seem to have spread far beyond the borders of Alajõe (as of writing, I have found no coverage of the case in either the provincial or all-empire press), the Russian Orthodox Church must have feared this would be the case. After cheating on her husband with two sacristans (among others), a priest’s wife had been viciously killed; another sacristan had been arrested for her murder and had sought to use incriminating material to blackmail his superior; and the priest himself had cheated on his wife with at least two women, while making the adulterous relationships the subject of pornography. Unsurprisingly, therefore, sacristan Boltov and Father Aleksandr were dispatched to new parishes. Boltov found himself in the province of Kurland (today western/southern Latvia), while priest Troitskii had to pack his bags for the island of Piirissaar in Lake Peipus, a parish even poorer and more remote than Alajõe. Sacristan Semen Karpin, though, escaped punishment, remaining in Alajõe until the collapse of the imperial order in 1917: he then led a reasonably successful career in the interwar Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church, being ordained as a deacon for a prosperous urban parish in Narva in 1929. With the Soviet invasion of Estonia, he was arrested by the NKVD before dying in a bombing raid.

Proving the old dictum that as a dog returns to its vomit, so a fool returns to his folly, both Troitskii and Boltov were unable to entirely move on from Alajõe. After serving as a naval chaplain from 1913, Troitskii, taking advantage of the chaos unleashed by German occupation and civil war, returned to Alajõe in 1918, where he started to intrigue against his replacement, Father Mikhail Nazarevskii, using family connections in the locality to do so. Although arrested by both the German and Estonian armies for his activities, he managed to get himself elected as a local schoolmaster and to turn parishioners against Nazarevskii, who was forced to vacate the position.11 In 1924, he gave up teaching in Alajõe to become the archpriest for the Pühtitsa convent’s Tallinn church, a position he held until his death in 1947.12

Boltov, too, ended up back in the region, becoming a teacher at the Lohusuu parish school (25.5 kilometres from Alajõe) in 1914. After a period of unemployment following Estonian independence, he was elected back to his old position as sacristan of the Alajõe Orthodox church in 1924. However, his second tenure was to be no less troubled. In 1929, Alajõe’s irate priest and agitated parish council decided to kick Boltov out, providing the ecclesiastical authorities with quite the rap sheet: allegedly, Boltov was repeatedly drunk, had called the priest an atheist during the liturgy, grabbed a female teacher’s behind during an Easter service, could not read or chant due to his advanced age, and ran an illegal moonshining business out of his apartment in the parochial house, among other indiscretions. Although the investigation found that some of these accusations could not be substantiated (indeed, the female teacher involved in the groping incident stated directly that Boltov had not touched her), Boltov was found guilty of insobriety and selling bootleg alcohol. So, he was forced to leave Alajõe a second time, even though some of his supporters caused a ruckus in the parish; as of writing, when and where he died are unknown.13

More than just a scandal?

Although it is tempting to linger on the insalubrious details revealed by the murder of Zinaida Troitskaia, the case does reveal something about the time and place in which it occurred. First, we can turn to Alajõe itself. Russian settlement on the northern shores of Lake Peipus dates back centuries, and with their presence came the Orthodox Church and its priests (as well as Old Belief, a variant of Orthodoxy that broke with the Moscow Patriarchate in the seventeenth century over the question of ritual reform: its adherents were frequently persecuted in the imperial era). However, Alajõe lacked a parish church until the 1880s, which left its inhabitants regularly cut off from religious services. Marshy, forested environs and virtually non-existent roads made the hamlet difficult to access even in the 20th century. Often, the fastest way to and from Alajõe was by boat over Lake Peipus, but this method of transportation could be threatened by storms and winter freezes. Its population of poor fishermen and women supplemented their income by working as farmhands for the more prosperous Estonian agriculturalists to the immediate north or, as the 19th century drew to its end, as part-time factory workers in Estonia’s expanding urban sprawls. The general lack of attention provided by the Russian authorities to these indigent lake people and the relative socioeconomic success of their Estonian neighbours led at least some to turn towards the Estonian language and religion. These poluvertsy (those of half-faith or semi-faith), as horrified Orthodox churchmen described them from the mid-1860s on, continued some Russian Orthodox practices, such as icon worship and fasting, but had abandoned their ancestral church for Lutheranism and had largely left behind the Russian language.14

In the 1880s, the imperial Russian state attempted to ‘russify’ the Baltic provinces of Estland, Livland and Kurland, a campaign mostly directed at ending the legal, administrative and cultural power of the Baltic German aristocracy. In such a context, the ancient Russian communities on Lake Peipus (and the threat allegedly posed to those communities by the Lutheran Church and non-Russian cultures) could not but garner the interest of senior figures. In 1885, Governor Sergei Shakhovskoi, a notorious russifier, resolved to come to the aid of the Russians on Peipus’s northern shores, most spectacularly with the construction of the majestic Pühtitsa convent between 1885 and 1892.15 Alajõe’s Orthodox community also benefited: as Governor Shakhovskoi commented, on receiving a request to build a church in the village, “I recognise a favourable response to their petition as extremely necessary for both strengthening the Orthodox of Alajõe parish in their expressed zeal and establishing Orthodoxy in Estland province in general”.16 The result was the founding of Alajõe parish in 1884–5 and the building of a church in 1889, using the redbrick and decorative accoutrements so distinctive of the national style of church architecture used to affirm a sense of “Russianness” throughout the empire. The establishment of schooling soon followed, with the village possessing two central parish schools and two auxiliary schools in neighbouring hamlets by 1910. The connection between Alajõe and the Pühtitsa convent was more than just symbolic. The convent sent its miracle-working icon of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary to visit the village once a year. And, more relevant for our story, Ivan Boltov worked as a teacher and sacristan at Pühtitsa before being sent to Alajõe.

It seems strange, then, that either the Russian Orthodox Church or the provincial government would allow clergymen without impeccable standards anywhere near their flagship project. Perhaps the answer to this peculiarity lies in the fortunes of russification. By the time Boltov and Troitskii came to Alajõe (1895 and 1899, respectively), russification was in trouble. The imprudent zeal of local actors like Governor Shakhovskoi and the Orthodox bishops of Riga made many of russification’s supporters in St Petersburg draw back, aghast. The arrest of 129 of the region’s Lutheran pastors17 for supposedly insulting the Orthodox faith and encouraging apostasy from it (both crimes in the Russian Empire) caused international scandal; having read about the persecution, the King of Denmark personally confronted Tsar Alexander III when the latter visited Copenhagen. Consequently, the russification campaign was disgraced even in the eyes of this most nationalist emperor: Shakhovskoi was only saved from dismissal by his death in 1894, while Riga’s new prelate (appointed in 1897) showed far less interest in either the Pühtitsa convent or its region than his two immediate predecessors.18 The revolutionary violence of 1905 convinced the Russian government to realign its interests with Baltic German landowners rather than the incipient Estonian working class or its long put-upon farmers.

It might therefore be conjectured that the low standard of Alajõe’s clergy, as revealed during the murder case of 1911–12, was connected to the declining fortunes of russification: no longer subject to intense scrutiny from the diocesan or provincial administration, scandalous behaviour in the Orthodox community may have been allowed to fester.

We must also consider the personal lives of the Orthodox clergy, the central cast in our story. For starters, let us turn to Father Aleksandr Troitskii and his grievance that, although he had not become a drunk in Alajõe, he was still being punished by the rumours swirling in the aftermath of the murder. Born in 1870 or 1871, Troitskii, the son of a priest, had attended the Riga ecclesiastical seminary before graduating in 1893. He then served as a sacristan at Riga churches until ordination in 1896, after which he was dispatched to a series of rural parishes near Lake Peipus, coming to Alajõe in 1899. It is customary in the Orthodox Church for priests to marry before ordination, meaning he would have met Zinaida in Riga.

Picture the scene: a young, relatively well-educated man, having spent years in the Russian Empire’s largest port city and having met his bride there, is dispatched to an isolated parish lacking anything even approximating educated society.19 Is it necessarily surprising that his marriage came under strain? Is it necessarily astonishing that both he and Zinaida sought entertainment in the form of love affairs, especially when Zinaida received the attentions of Semen Karpin, a man some 13 years her junior? Perhaps not.

On top of this came all the burdens of pastoral service. This was not simply limited to liturgical services on a Sunday in the village church. As of 1910, the Orthodox parish of Alajõe was 1,118 people strong, many of them not resident in the village itself, but scattered in surrounding hamlets.20 Long and potentially gruelling trips by horse and foot were required to provide baptisms for sickly newborns and last unction for the dying. Although assisted by his sacristans and peasant teachers, Troitskii was ultimately responsible for providing the elementary education the parish offered to 80 boys and girls.21 And finally, Troitskii was expected to offer popular education to the peasant masses, which he did as part of the region’s sobriety movement: from March to May 1907, for instance, Father Aleksandr gave five lectures: on the life of the Virgin Mary, dental hygiene, stars and comets, the Slavic folk holiday held on Kupala night,22 and (ironically enough) marriage. Such talks were accompanied by magic lantern shows, brochures, a gramophone, and, sometimes, a folk choir.23 At least as a priest in the borderland Baltic provinces, Troitskii received a relatively good salary from the Russian state and so was spared the indignity of haggling over charges for the performance of rites or working the soil (unlike many of his colleagues in the Russian interior). Not that there was any soil to work in Alajõe: when the parish was created, no agricultural land was given to the clergy, since its sandy quality made it useless for growing produce. And while Troitskii got to live for free in a relatively new parochial house, later descriptions of the building depict it as small and cold.

Perhaps one of the few bright spots for Troitskii was that the parishioners of Alajõe were disinclined to social discontent. While violence and disorders broke out elsewhere across the empire’s Baltic littoral in 1905, the residents of Alajõe hastily affirmed: ‘We do not desire to deviate from the duty of our most loyal oaths and as before remain loyal subjects of our lawful sovereign emperor Nikolai Aleksandrovich [Nicholas II] and his lawful heir. We absolutely do not desire the fragmentation or division of the single Russian tsardom, nor do we hope for any kind of republic. And if there are dishonest people, forgetting the oaths given before God and rising up against the law and the lawful sovereign, then we ask that they be pacified by the means possessed by the lawful government. We, despite invitations to arm ourselves, are not raising a sword against anyone. But the sovereign emperor knows that in case of necessity, at the imperial call, we will provide support not to the mutineers but to him, our lawful sovereign emperor.’24

Confronting a heavy workload and backwoods monotony, the choices of the Troitskiis were further limited by the strictness of the Russian Empire’s divorce law. Unlike in much of the rest of Europe at the time, divorce in the empire, along with other forms of marital dissolution, remained in the hands of the Russian Orthodox Church, which was extremely reluctant to grant it even to laypeople, let alone the clergy. Of the 15,502 divorces requested in 1913 in the Russian Empire, only 4,000 were granted; in France, the number was three times higher and in Germany eight.25 Indeed, to even stand a chance of obtaining such a separation on the grounds of adultery, a confession or incriminating material evidence was not sufficient: eyewitness testimony of the unfaithful act had to be provided. But even had Father Aleksandr and Zinaida sought a divorce, it does not take a great act of imagination to conceive of the social opprobrium to which both would have been subjected: readers who have browsed Anna Karenina will have some notion of the stigma attached to even rich, aristocratic divorcees in the Russian Empire. Nor could Father Aleksandr have remarried: according to the customs and laws of the Orthodox Church, a priest cannot marry after his ordination. All of this, no doubt, made the Troitskiis’ lifestyle of shrugging their shoulders at each other’s infidelity more attractive than any other option.

Finally, why did Ivan Boltov seek to blackmail Father Troitskii with the salacious photographs and pictures he obtained at some effort and cost? Boltov repeatedly argued that he and Troitskii had had a perfectly serviceable relationship for more than a decade. However, Boltov also declared that he had been burnt before: his good rapport with Troitskii’s predecessor had apparently curdled, leaving Boltov vulnerable to the priest’s ill will.

All this speaks to the much abused position of sacristan in the imperial Orthodox Church. The non-monastic clergy were essentially divided into two ranks: ordained (priests and deacons) and non-ordained (sacristans and readers). Although the socioeconomic position of priests left much to be desired, they were better paid, better regarded, and better educated. Sacristans, bearing an onerous workload of chanting, accompanying the priest during the performance of rites, teaching, and secretarial duties, got scarcely a fraction of the money received by their superiors: in our case, Father Aleksandr received 1,300 roubles a year, while Boltov got 300 (Karpin, even more disadvantaged by being the junior sacristan, was paid 250).26 On this sum, Boltov had to maintain not only himself and his wife, but also his five children. His chances of promotion in the Church (and thus increased remuneration) were slim, since he had not attended the seminary, a near-mandatory requirement for imperial-era Orthodox priests. This might have irked Boltov in particular, since details of his biography indicate he was something of a social climber. Born a peasant in 1868 in Mustvee (roughly 38 kilometres south of Alajõe), he had completed his parish schooling by 1881 and earned the right to educate: he had then been awarded a teaching job in 1887 at the emerging Pühtitsa convent, a prestige project of the provincial government. All in all, Boltov had good reason to be afraid, jealous, and angry at his immediate superior, a toxic concoction that may well have paved the road to blackmail and, perhaps, even murder.

Conclusion

On the night of 1 December 1911, Zinaida Troitskaia met a tragic, violent and untimely end, already dead when her young lover Semen Karpin leaned in to hold her hand for the last time. Whether she was the victim of her husband’s jealousy, Boltov’s anger (born perhaps of unrequited advances), or Karpin’s cold calculation, we will never know. But, as all historians are aware, light is often only shone into the inner workings of communities and the private lives of individuals when they are disturbed by events dire enough to attract outside attention. This much is true of Alajõe, then as now mostly ignored. Zinaida’s demise throws much into sharp relief: the fate of a discarded project to fortify Orthodoxy in a hitherto neglected imperial borderland; the travails of an Orthodox priest and his wife sent from a city to serve in the deepest countryside; the love affairs that perhaps gave them relief from toil, boredom, and each other; the laws and mores that kept them bound together, regardless of personal antipathy; and the poisonous acts bred of the structural inequality between priests and sacristans. The extent to which any of this was representative or exceptional in either Estonia or the Russian Empire will come to light as scholars continue to comb the archives.

1. EAA (Estonian Historical Archive) 1898.1.64 (unpaginated).

2. All details of the murder and the subsequent investigation are provided from EAA.105.1.11294.

3. All dates are given according to the Julian calendar (in use in the Russian Empire until 1918).

11. For Troitskii’s activities in Alajõe in these years, see EAA.1655.2.2590.2-47.

12. Data on Father Aleksandr Troitskii’s subsequent career comes from Andrei Sõtšov, “Eesti õigeusu piiskopkonna halduskorraldus ja vaimulikkond aastail 1945–1953” (MA thesis: University of Tartu, 2004), 174.

13. Details of Boltov’s post-1912 life and service can be found in EAA.1655.2.2738, EAA.1655.2.2739, and EAA.1898.1.70.

14. EAA.1655.2.161.5-5ob and EAA.1655.2.172.3-3ob for descriptions.

15. See J. M. White, “Russian Orthodox Monasticism in Riga Diocese, 1881-1917”, Canadian Slavonic Papers, vol. 62, no. 3-4 (2020), 377-379.

17. See K. Weber, “Religion and Law in the Russian Empire: Lutheran Pastors on Trial, 1860-1917” (PhD dissertation: New York University, 2013).

18. For this narrative, see A. Polunov, “Imperiia, pravoslavie i problema reform v Pribaltike: k istorii religiozno-politicheskii bor’by 1880-kh – pervoi poloviny 1890-kh gg.” In I. Paert, ed., Pravoslavie v Pribaltike: Religiia, politika, obrazovanie, 1840-e – 1930-e gg. (Tartu: Izdatel’stvo Tartuskogo Universiteta, 2018): 207-227.

19. There is some dispute in the sources as to whether Troitskii came from the rural Estonian parish of Laatre or St Petersburg. If the latter, it would add substance to the argument that Troitskii was a city boy, completely over his head in rural locales.

22. 24 June in the Julian calendar.

23. EAA.1898.1.60 (unpaginated) and EAA.1898.1.64 (unpaginated).

24. EAA.1898.1.58 (unpaginated).

25. G. Freeze, “Profane Narratives about a Holy Sacrament: Marriage and Divorce in the Late Imperial Russia” in M. D. Steinberg and H. J. Coleman, eds., Sacred Stories: Religion and Spirituality in Modern Russia (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007), 148-149. The populations of France and Germany were also notably smaller than the population of the Russian Empire.

Dr James Matthew White is a research fellow in church history at the University of Tartu. His book Unity in Faith? Edinoverie, Russian Orthodoxy, and Old Belief, 1800-1918 was released by Indiana University Press in 2020. He currently specialises on the history of Orthodoxy in the Baltic region. He received the 2020 Canadian Association of Slavists Article of the Year Award for his article “Russian Orthodox Monasticism in Riga Diocese, 1881-1917”. He is the creator of www.balticorthodoxy.com, a digital resource for the history of Orthodoxy in the Baltic region.

This article was written with the financial support of the Estonian Research Council, grant no. PRG1599

© Deep Baltic 2023. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.