“Eastern Europe” is a phrase that is often disliked and rejected in this part of the world – many over recent decades have argued that the countries often referred to by this tag in fact share little bar their experience of Communism (and that many are not even very far to the east). The recently published Goodbye Eastern Europe by writer Jacob Mikanowski, born in Pennsylvania to Polish parents, admits that “the phrase Eastern European is an outsider’s convenience, a catchall used to conceal a nest of stereotypes”, but makes a contrary argument, claiming that actually these countries do have a fair number of things in common – although one of these commonalities is, or was, their sheer internal diversity of ethnicities, languages and religions. As he puts it, “where empires tried, and failed, to impose some kind of uniformity, at least at the level of administration, tradition conspired to create a society of almost infinite heterogeneity“. As this quote suggests, this Eastern Europe is a land of comparatively small countries, wedged between great powers: almost all the countries in the eastern half of the continent share the experience of having been ruled from a different capital, whether Vienna, St. Petersburg or Istanbul.

Ranging over 20 modern-day countries, and showing a deep knowledge of the history and cultures of the region, Goodbye Eastern Europe reveals a part of the world characterised by multiplicity, flux and contradictions. Delighting in historical anecdotes and bizarre facts, and weaving in personal experience and the dramatic stories of his extended family in and around Poland, we learn, among other things, why these countries are united by the (reputed) existence of vampires, as well as wanderers and heretics of all religions and faiths, such as the mountain-dwelling Hutsuls of the Carpathians, who believed the world was originally made out of sour cream. The Baltics make regular appearances: whether writing on the “bitter polemics” sparked by proposals to introduce the letter “y” into Estonian, an alleged case of a benevolent werewolf in what is now Latvia, or the Karaites, a tiny Jewish splinter group of a few hundred who lived in Trakai near Vilnius, and in the 1930s were producing at least five journals across three distinct languages and alphabets.

In a world characterised by overlapping cultures and vague borders, the experience of the founder of Hasadic Judaism, Baal Shem Tov, born in Podolia in what is now Ukraine, is far from extraordinary: “it is characteristic of Eastern Europe that the childhood of this Jewish mystic would unfold inside a Polish-Catholic citadel, among Orthodox Ukrainians, in view of Turkish minarets.” Following the story into the 20th century, the picture darkens but continues to differ markedly from countries to the west, as we see the rise of nationalism in the faltering empires, the massacre of much of Eastern Europe’s Jewish population, and then the postwar dominance of Communism across the region. However, in an essay on the same subject for The Los Angeles Review of Books, published in 2017, Mikanowski argues that Eastern Europe’s distinctive qualities are slowly disappearing, a result not only of the destruction of the last century, but also of globalisation and (in some parts) unprecedented prosperity. Deep Baltic’s Will Mawhood spoke to Jacob Mikanowski several months ago about the book and his long-standing fascination with the region.

I wanted to begin by asking a little bit about something you say about diversity in the region – obviously that’s one of the qualities that you find particularly fascinating in the region. And you use this phrase that diversity in the region has – or had – a “fractal quality”, which – my understanding of fractals probably isn’t perfect, but kind of patterns that recur in different ways, so talking about ethnicity, that’s in certain areas having different groups that are at different levels on the social spectrum perhaps or do different jobs, and those tend to recur, although obviously in different ways throughout Eastern Europe.

It seemed to me, in a way the book itself is quite fractal, because you have these themes that recur in similar forms again and again throughout the region, although they’re quite different. And you have these subjects that the book is arranged around, such as minorities and religions, and you talk a lot about, for example, heretics being a characteristic feature of the region. I was curious why you decided to structure the book in that way. Did you think about doing it a different way, or did that just seem the most logical way to do it, around particular themes?

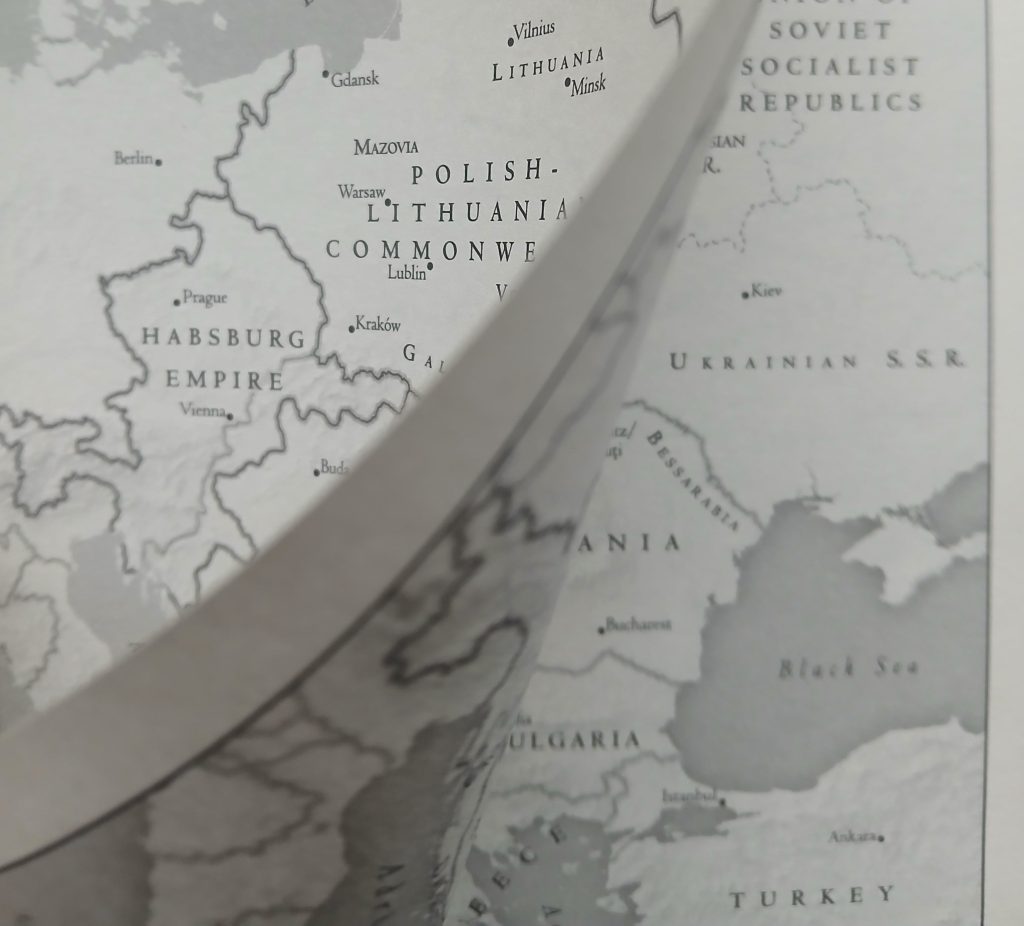

That’s a great question. To me, fractal diversity – the element of fractals I was thinking about was infinite zoomability, that the same pattern, the same kind of complexity recurs at whatever scale you go. You can do it at one zoom, ten times zoom, one hundred times zoom. The further you go in on the map – zoom in, zoom in, zoom in, the same patterns recur and recur and recur. So in terms of ethnic diversity, the old Eastern European pattern was you had provinces – or modern-day countries – which would have tremendous diversity. You know, Transylvania, which we were just talking about, had that: if you look on a wide screen, mapped on a small scale you’d see these patches of Hungarian and Szeklers and Romanians and Germans. Or if you zoom in and zoom in and zoom in and get down to the cities, cities had that multi-ethnic pattern recurring, villages had it, and even the small towns would have – once upon a time at least – their Jewish tavern-keeper, their Catholic landowner, if you’re in Lithuania, or in eastern Poland, their Orthodox peasants. Or you can have those elements recombined – so that it could be a Muslim landowner in Bosnia, and Christian peasants and Greek merchants, but those patterns recur and recur.

And what I like about it – I like to tell history from below, more than from above. That’s for a couple of reasons, kind of disciplinary reasons: I like micro-history, I like stories of ordinary people, regular people –peasants, merchants, cobblers, the experience of history from that level. And I’m less interested in rulers, kings, princes, emperors. There’s also a family element, because there’s a personal element to it, which I try to use. I didn’t try to use the book as a family history, but these elements from family history to illustrate these points.

And, you know, my family has different origins. They have some extraordinary stories, but in most cases ordinary people. When you have that interest in the level of the ordinary, of the village, and the merchant and the regular person, you want those multiple scales, you want to see how the macro affects the micro. And I’m more interested in the experience of the micro than the macro in a way.

And part of that’s a little strategic, in terms of when you have Eastern European history, a lot of that history isn’t written in Eastern Europe – a lot of it is dictated from Moscow, it’s dictated from St. Petersburg, it’s dictated from Istanbul, it’s dictated from Vienna. The political history is kind of off the map, it’s not happening in the Eastern European heartland of the borderlands. So I like telling it from the opposite side – telling how the war affected people on the ground, rather than who started the war. So multiple levels.

And also the complexity of the region means that if you try to go in and tell the political story of every one of 19 or 20 countries, that becomes overwhelming. But if you focus on themes or experience, you can kind of find a way to it. If you look at most larger histories of Eastern Europe – and there aren’t that many, really – they will go country by country by country, and that is an approach that I think that quickly becomes overwhelming. You go interwar Europe, and you’re remembering 20 presidents and 50 political parties, and that gets too much. So in a way, having that complexity makes for a simpler story, a thematic story rather than a comprehensive political one.

Well, yeah, it’s very difficult to be an expert on Eastern Europe, because as you said the sheer number of languages, and most countries have quite different histories, and cultures that don’t necessarily intersect, or intersect in some ways. I think often you see people described as an Eastern European expert, and they focus mostly on Russia or on Poland perhaps or on the Balkans. But it’s very rare that someone can cover all of those. So that must have been a huge challenge trying to work with all those sources and languages.

It was, and that dictated the approach too. To have these larger themes that the book is around lets you draw in material from a lot of places without being… you know, my expertise is much more in Poland, and a larger Polish-Lithuanian experience, and then probably stretching that to the former Czechoslovakia, Hungary, which is what I studied in graduate school. But having a little bit more flexible structure let me draw in from further afield, where I wasn’t that familiar, I’ll say – especially as you go into the Baltics and the Balkans, the book involved a lot of travel for me, and a lot of discovery and a lot of finding things out that were completely new to me, that I hadn’t studied. I did a history undergrad and a history PhD, but that touched very lightly on the periphery of Eastern Europe. So writing the book was an education in and of itself.

You mentioned your family story, which is very interesting and complicated in itself and I hope we’ll have the chance to talk about a bit later. But I’m kind of curious because I know a lot of people who have roots in this part of the world, and it tends to be the case that they are very interested in the country that they are a kind of diaspora member of, but I find it’s very unusual for people to be interested in other countries [nearby], other than the country they have a family connection with. So I was curious where this interest in the region as a whole comes from.

I do think there’s a way in which my family background affects that. I’m from a mixed Polish-Catholic/Polish-Jewish family. And the Catholic side has roots in Lithuania, and the Jewish side is mostly eastern Poland and then some other Polish roots kind of towards the Czech border. But that split Polish-Jewish identity means not being fully in either camp – I didn’t feel fully part of the Jewish world, I grew up with a lot of secular Polish Jewish culture; it’s a very odd and almost vanished type of commitment, a specifically Jewish approach to Polish culture, which leaves you a little out of the Jewish mainstream, a little out of the Polish mainstream. So the problem of Eastern Europe became really interesting to me, the problem of being in between and having a foot in two places. I actually am very interested in Polish culture and the Polish language and Polish literature – but as a historian, I wanted to look beyond the national, into the multi-national and that multi-ethnic past, which I feel I carry a little bit of that inside me, the multi-national aspect to history was what really drew me in to study Eastern Europe. And the more you study Eastern Europe, the more you see that everywhere.

There are a lot of historians, a lot of people, who bring that national frame and see it as, you know, the history of Slovakia, the history of Romania – the history is bounded by a modern-day or 20th-century border. But the further back you go, those borders disappear, and the borders between nationalities start to disappear as well, and you start to see that the big structuring forces in people’s lives were more about religion and belief; political and spiritual beliefs really kind of orient people’s lives. Even just going back to my family: I knew my grandparents pretty well – I lived with them in Warsaw – and they kind of come out of that world, that in some ways lost world. There are bits of it left, but that’s the past I got drawn into. And that is – I think you’re right – an approach that… because I talk to a lot of people with heritage in the region, diaspora communities, and that interest usually is either national- or minority-based, but usually not full. But I was hoping that the book could reach across some of those boundaries.

If I understand, Jacob, you’d been studying the region for quite a long time academically prior to writing the book?

That’s right, yes.

Because you have this – I can’t remember if this was something someone said to you or if it was a story you heard – but you mentioned a student asking if people, I don’t remember the exact quote, but something like if people actually laughed in these kind of grey countries…

Yes, he asked if Eastern Europe was really a grey place where people hardly ever laughed. That’s a professor I know in a neighbouring school to mine, we had a workshop on Eastern European history – everyone in my area of California who would work on this region would meet and would look at papers –and one day he mentioned that as an anecdote, which is true to the experience of teaching or trying to teach this topic in America. The mental map of Europe for Americans is usually reasonably well defined in the West, and very vague in the East. People have a mental idea of what France is, what Italy is, what Great Britain is, what Spain is, and the further east you go, the more the geography is vague in people’s minds, and the actual imagination of it is also under this cloud of stereotypes. But that’s a real quote – second-hand, but that’s a real quote someone said.

And it’s a sentiment you meet with pretty frequently. People are much less likely to have been to Eastern Europe than to Western Europe, and if they’ve seen Eastern Europe depicted, it’s usually not in the most flattering light, in movies where it’s a kind of backdrop for something depressing, something post-Soviet or something criminal. It’s rarely a positive depiction, and it’s rarely very specific; Eastern Europe has this kind of gloomy question mark around it. Some people – like the heritage people you speak of who have a very intimate connection with a part of it, that’s not true at all; they have a very strong attachment to a certain part of Eastern Europe. But for people who don’t have that connection, or people whose ancestors emigrated usually before World War I or certainly World War II, most commonly it’s an other place, it’s a dark place. I speak to a lot of Jewish groups, Jewish organisations, and one or two generations out, Eastern Europe is just the old country, it’s just a place of kind of anonymous suffering. And rarely does it happen to be filled out with a more specific, concrete image.

And have you noticed any change in that during the time you’ve been interested and involved in the subject?

I think so. I do think that people, and this goes with the theme of the book, more and more people are warming up to Eastern Europe, more and more people are going. I think within Europe that’s more true than in America.

Well, it’s a lot easier to go.

Yeah, it’s a lot easier – it’s a lot easier for British or French people to go. But overall, definitely the part of Eastern Europe that’s been in the EU the longest – you know, Poland, Czechia, Hungary – have kind of come into the map much more. Kraków, Prague, Budapest have kind of migrated into Western Europe or the European mainstream – Croatia very much. So the border where things get kind of vague has shifted. And also people have this immense emotional connection to Ukraine since the war. I’m in Portland, and there are Ukrainian flags still all over town. So there are different attachments. And things certainly have changed since the ‘90s, there’s been an evolution.

But then for many people it’s still one homogenous, undefined mass. The sad truth is that geography and history aren’t the strongest subjects in American schools. And certainly if you go with Eastern Europe, you’re almost always off the map. Even people who study European history in history departments, which is in itself rarer and rarer, will rarely venture east of Germany, and if they do it’s let’s say Russia. So it’s still a topic, a subject, an area that is probably the least-known in Europe, even now, with some exceptions.

Well, yeah, it’s certainly something I can identify with, a lot of those comments you’ve made about the perceptions, in the UK – with some exceptions.

I was kind of curious because, talking about that impression of the region being this sort of grey and depressing swathe of lands that no one knows anything about – but it’s not worth knowing about. It’s really striking how – I would say probably deliberately – lively and colourful your book, and the anecdotes in your book are. I wrote down a few examples that I found pleasing or intriguing, but they’re all slightly kind of eccentric.

So things like Black Weddings in Poland, this kind of amazing tradition I knew nothing about at all. You had these stories about “Magic Prague” under the occult-obsessed manic collector Rudolf II; a story about putting someone called Baron von Chaos in charge of the Royal Mint; a school for training dancing bears; the fact that Slovene has 48 dialects; the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph considering it unsportsmanlike to arrest the chief of the Serbian general staff even though he was in Budapest when they declared war; Béla Kun, the Hungarian Communist leader escaping in a plane with his pockets stuffed with pastries; handbooks for the suppression of miracles – I think that was in Communist Poland.

I mean, these are quite the opposite of grey. I was wondering if that was something deliberate, or if it’s just impossible to write about this part of the world without those kinds of stories.

No, it’s very deliberate. You know, here’s an alternate way of telling the story, which is to focus on death, destruction, murder and war. And that’s part of the experience too – very much part of my family history. The “bloodlands” narrative – which isn’t false. Eastern Europe is Europe’s heartland of diversity, and also probably because of that has suffered some of the worst violence, imposed from outside and internal violence, especially in the 20th century.

But I love Eastern Europe, I love Eastern European culture, the Eastern European novel. It isn’t one culture: there’s kind of a nest of related cultural traditions that have affinities. The Czech novel, Polish poetry, Ukrainian foodways… you can go on and on. Romanian modernism. There is so much that I find fascinating.

And part of it is a style of storytelling that I grew up with. I start off the book with a story from my great-aunt, and her three aborted attempts to get married in and around World War II. And that vivid, funny, sardonic style of narration where people wouldn’t tell the whole story of their lives, they’d boil it down to these often kind of ridiculous anecdotes. The style of story-telling you get in Babel – in great Russian-Jewish or Polish-Jewish fiction. But it’s all through the region, you find – the Czechs are probably the best at it. And there’s laughter and there’s tears. I love the bizarre, the funny, the tragic – and there’s just tonnes of it.

You know, [about] Magic Prague – there’s a whole book called Magic Prague by an Italian literary scholar called Angelo Maria Ripellino, that is just passages of the strangest, most bizarre stuff pulled from the history of Prague and the depiction of Prague in Czech literature – it’s just a goldmine. And you go around Eastern Europe, and literally I would go around to places and just stumble on these fantastic stories.

Like the prophet Klimowicz, a Belarusian prophet who declared himself the second coming of Christ, and then the villagers two villages over came to crucify him and he hid in a potato cellar. I found that story by actually being in that area and just encountering it on a local plaque. Going places, you find the most amazing things wherever you go, every stone you turn over.

So I wanted a book that made a case for Eastern Europe being as culturally vibrant as any other place on Earth, as culturally interesting, as historically vivid and fascinating as any place on Earth. Without downplaying the violence too much, but not letting it take over the entire story.

Talking about it as you say being structured around these little anecdotes, it reminded me of the kind of stories people tell you in pubs at odd times of the night. It has that… it’s quite unusual for a book of its kind in that way, being built around these little stories.

You asked me about the fractal thing. One thing that dictated is that I wrote it a bit in a reverse way from what you would expect, where I gathered my stories, my anecdotes and little tales and built chapters around them. I love the Russian skaz, for instance, that almost folk-tale-type narrative that distils experience into little nuggets, and then builds the history around that. Because I really love that level – it makes me think of what I think is my favourite story in the whole book, which is also an accidental discovery, is the president of Czechoslovakia whose ashes were eventually kind of forgotten in a pub in 1989 and never made it to their burial place. So the pub even kind of pops up there.

You know, the guy who was mummified and then they had to cremate him and then they took the ashes and they had to do something with him after the Wall came down. First the guy went to stop in a pub and had a drink, and left the ashes there.

That’s very Czech.

Exactly – that kind of pub tale. There’s still so much of that history.

Related to that, I was wondering if you think there is a risk with this kind of narration and presentation of swinging into… There’s another way that Eastern Europe is seen sometimes I find, which is also quite stereotyped and quite vague but – an example, perhaps an unfair example would be things like the film Everything Is Illuminated. I haven’t actually read the book of that, maybe the book is great, I’m not sure. But this idea that people are all a bit mad there, these kind of wild mood swings, terrible things happen there, but… I don’t know, there’s a sense I find in that kind of fiction or films where everything’s a bit manic and very funny, but it almost seems to dehumanise the people in a way. I don’t know if that makes sense, how well I’ve explained there.

Because I’m sure – I mean, I know this for a fact – if you looked at the history of England there’s a lot of bizarre and comical and slapstick stories. But there is this perception about Eastern Europe, that everything is kind of a bit crazy here.

You can easily slip from the exotic to exoticism, I think that’s what you’re saying. And I think that’s absolutely true – you can go from the unusual and the odd, into this kind of sweeping “this is history’s madhouse”. I think that’s true. I think that’s a risky one as a writer, and a risky one talking about this as an area.

I find, maybe this is more of an American perspective than a European one, but I do find that the first enemy you’re overcoming as someone talking about Eastern Europe to a foreign audience, an audience outside the region – you first have to overcome indifference and then ignorance. You have to first break down that barrier of “this is that grey place where no one ever laughs”. And the other perception is “this is just history’s charnel-house, a place of murder or suffering, which my ancestors justly fled from”.

So that’s what I’m pushing again – to say: no, this is a unique and uniquely rich human landscape that has had also some of the most extreme experiences in all of human history. I do think it’s important to grab the reader, and then to interest them, and then educate them. So I’m willing to run that risk that Everything Is Illuminated runs – which is a book I have mixed feelings about too – and try and steer between those two poles: of Gogol Bordello and Bloodlands. To draw people in and then present the fuller history. That’s a tightrope and it’s hard to manage, but that’s a tightrope I’ve chosen to walk. I hope it seems judicious in the end, but I can see it falling by the wayside. I hope that makes sense, because I think that’s a valuable question.

The next thing I wanted to ask about is a quote I’ve got from the book about one of these themes you say is common to a lot of these very different countries, which is vampires, or people who have returned from the dead, which is intriguing – I hadn’t thought about that at all.

The quote is: “While the word upiór seems to have a Polish origin, the belief in a specific kind of returning, malevolent dead was common to most of Eastern Europe. Indeed, it was present in every Eastern European country except Estonia and almost absent from any of its surrounding neighbors, aside from Greece. Eastern Europe can be said, in a way, to be vampire Europe—bound by an invisible web of beliefs about what the dead might claim from the living, and how they could be warded off”

I’d definitely like to ask about “vampire Europe”, because that’s a fascinating concept in itself. But simply in terms of where you’ve drawn the lines, I was curious by what was included and was excluded from that definition. Because you say it didn’t apply to Estonia, it does apply to Greece.

Knowing Estonia quite well, I did feel that at least some of the things you gave as being quite common to the region as a whole: certainly the presence of Jewish minorities, obviously Muslim minorities as well, also Roma to a large extent, these kinds of small religious groups in general. I felt, that’s already much less true when you get to northern Latvia, and I find with those aspects at least it’s not really true at all of Estonia. But obviously, any kind of concept like this will be very debatable. But I was curious if you think you could reverse those two: could you write a book with the same concept that excluded Estonia and included Greece?

Absolutely. Absolutely. And that a little bit points to the artificiality of Eastern Europe as a catch-all as a region: no single set of features makes it a perfectly delimited single region, and on the borders, on the edges you get a lot of variation. There’s kind of a core ultra-diverse zone in Eastern Europe, which really isn’t bounded by nation. It would probably be a belt that starts in south-eastern Latvia and went through Lithuania, through eastern Poland and western Ukraine and western Belarus, down into Romania, and towards Northern Macedonia, Albania. If you imagine you have a belt through there, that’s the kind of core Eastern Europe. And the further you get away from that, the less some of those features apply.

And Estonia’s interesting, because just as you say a lot of that religious, ethnic diversity is much less present. And it’s very present in northern Greece – northern Greece really has everything I’m talking about in terms of Eastern Europe. However, Greece as a country, almost by convention, is somehow part of the Balkans but never part of Eastern Europe. Maybe it’s too maritime, maybe it’s too close culturally to both Turkey and Western Europe. It actually fits in in a lot of ways, although Greeks do not like that idea. But northern Greece very much in terms of its human landscape and history fits very well into it. And really if you’re in the parts that were Ottoman until 1912, just as well as Albania or as Macedonia.

Whereas Estonia, as you say it has this long history with Sweden, in some ways its history is closer to the world of Lutheran, of a kind of Northern European Protestant story that is quite different from the Catholic-Orthodox borderlands of the rest of the book – Catholic-Orthodox-Muslim borderlands. And yet Estonia as a country has a story that fits in much better with Eastern Europe than Greece does. As a country, it has a history of a fairly short period of independence, of fragile nationhood, of being dominated by one or more large neighbours, of fighting to resurrect a culture, and that fight being oriented around the language. Its national story, its national revival is a very Eastern European one. Its local ethnographic, social, religious story is less so. So it kind of has one foot in, one foot out. And ultimately I kept it in and I put Greece out.

And you could say some of the same things about East Germany. East Germany’s not really part of this book – I kept it out. Going the other way, Greece is out, Crimea could be in – it has a lot of features, but ultimately it’s a little too far. And I get asked why isn’t Georgia in this book? Well, that’s going too too far, although you’ll see with Eastern Europe Georgia now is covered – when people do political history or people do travel, they all get lumped in. But that’s a bridge too far.

But I find these border questions very interesting.

The thought came to me, I think when I was reading your book and I was specifically in Western Estonia, in Haapsalu, that area – I’ve got a friend who lives out there. And there you’ve got the Swedish minority who have historically lived there, visually it does just look exactly like Scandinavia, in a way that – you get that a bit in the north part of Latvia, but it’s still a different feeling. But I think the east of Estonia is very different – you have these large Old Believer communities, as I’m sure you know, along Lake Peipus. But of course you can be in overlapping worlds at the same time.

I think that’s true. It’s sort of the most Scandinavian part of Eastern Europe, the most Eastern European part of Scandinavia.

There’s a way that Czech history, Czechia is also almost like a piece of Western Europe in its characteristics. It has this economic history, urban history that’s very much closer to Western Europe, really. Because it was so industrialised and so urbanised early on. But it has that Eastern European style of struggle for existence, struggle for national realisation – that kind of puts it in, very hard to leave it out. It’s also just very far west if you look on a map – Prague is west of Vienna – and yet it has something that clusters it with the east. But these are all flexible definitions that I think ebb and flow.

And going back to “vampire Europe” – why do you think that is, that the region broadly is so characterised by these stories?

I was wondering if it had any kind of relation to something else you bring out well in the book, which is the extent to which until comparatively recently lots of the region was a kind of frontier, that large parts were unsettled or had become depopulated. That there are really frightening and mysterious things lurking out there. Living in the Baltics, maybe you get more of an acute awareness of that dynamic – because they were subject to crusades from the west. I guess some of the qualities of (German) Prussia in particular may have come from that frontier history, the fact that they conquered and partially wiped out the previous inhabitants.

I think there is something to an idea of an enduring frontier, especially a frontier between religions and modes of belief. On one hand, there’s the late arrival of Christianity and the persistence of paganism –something especially true of the Baltic; on the other, the multiplicity of religions, and the relative weakness of states, which prevents the kind of mental and ethical pruning Catholic and Protestant authorities were able to perform in Western Europe. The result is a much wilder garden of beliefs – some very old, reaching back to times before recorded history.

The other thing is the sheer presence of the dead. In a part of the world where fate can be so capricious, and death so unexpected, perhaps it’s natural that the dead acquire some additional psychic real estate, and demand, in a sense, to share space with the living.

Mentioning as you did the way that Estonia best fits into your version of Eastern Europe through having quite a short existence as a state. That I think is one of the defining qualities in your book of Eastern Europe as a concept. And you talk about I guess when you were living in Poland in the ‘90s or maybe the late ‘80s about hyper-inflation – I can’t find the exact quote*, but you said it gave you a sense of fragility of money, things that a lot people would take for granted.

And I’d just say that, personally, my experience having lived in this part of the world for a long time – I do find friends, relatives in the UK, I think there’s a lot of things they really take for granted as just being stable. And I think I’m always conscious now that countries could stop existing, everything could collapse. I imagine you would understand that, but it’s something that I really don’t think most “Westerners” do.

That story is from I think ‘92, ‘93, when I was there and a relative… because the woman who raised my mother – who wasn’t her mother – had died and we were looking for her life savings. They were in one of those old Danish butter cookie tins that a lot of people used to have, people would keep their sewing supplies in them, often grandmothers. And that’s where she kept her life savings, and they were in cash, and that cash was worth – and she was dead, and we really didn’t have anyone to pass it onto, we found a cousin of hers – but it had dwindled to far less than a dollar. The total of the life was some clothes, some religious images, and pennies. It just evaporated, it disappeared.

I was reading a memoir by a woman, a Polish woman, from a very grand, very important family, actually in Belarus, Lithuania and Latvia – the Puttkamerows. I think they had a presence in Latvia, I know they went to school in Tartu. You know, multiple states, one of these great Polish houses. And she had a very lavish childhood, and everything she’s writing about from before World War I – she’s writing in exile in London in the late ‘40s – none of that exists anymore. “We’re from a part of the world where nothing lasts, everything burns.”

And that’s… even though things have been very, very good for the past 30 years in much of Eastern Europe, certainly in Poland, that sense of existential unease I think is still there. I was in Poland in March, and the Polish economy was doing probably the best it’s done in 400 years – I saw these headlines that it was the best time since the Golden Age of the early-17th-century grain trade, and I think that’s probably true. People are prospering, things are pretty positive. And I was shocked at the sense of unease and dread and fear, how much the war in Ukraine and the presence of Russia had put people back on edge.

Because I have this memory of everyone’s accumulated savings just going “poof” in the ‘90s. People older than me have this memory of martial law, or much older, the German and Soviet invasions – people in the Baltics probably have some of that too – that feeling of: we have this now, but it could always disappear, it could always vanish. And I think that’s not part of the Western European experience. In Britain, the last successful invasion was a solid thousand years ago. So you can rest easier even if things aren’t materially that much better.

Well no, I mean, that’s another question. The gap used to be a lot bigger – certainly when I first came here.

Just staying with that subject for one moment. Because something you mentioned, I think this was actually in the original essay you wrote for The LA Review of Books, where I assume the book came from that – or maybe you were writing it before.

No, it actually came out of the essay.

In that, again, I’m kind of paraphrasing, but you said that the quality that I think a lot of outsiders would characterise Eastern European fiction in particular – I mean, cinema as well to an extent – but certainly literature, as having, which is this sort of absurdism, is linked in a way to that feeling of instability. You know, your country could collapse, you could wake up in a different country, awful things could happen to you, you’re not really protected – no one really cares, as well. I was curious if you think that is linked to this kind of historical experience – and if that’s always been something true of the region, or if it’s more of a 20th-century thing.

I think that’s certainly true in the 20th century. I think going back further, it can be hard to tell because the further you go, the more you’re in a world really of social castes and identities that no longer make sense – noblemen or peasants or serfs that really belong to a pre-modern world. But in the 20th-century – the 19th century too – there is something distinct about the Eastern European novel, Eastern European narration. In the 20th century it’s the most true.

American novels – it’s hard to generalise about all national novels, these are very wide generalisations, take them with a grain of salt. But there’s an idea of: you shape your destiny. You’re in this big wide open country, and you make your destiny, make your life measure up to it, you’re going to shape your own life and see if you succeed or fail. And Western Europe is more kind of – there are these very tight social structures, and you find happiness within them. Like Jane Austen. There are so many mores around wealth, and around marriage, and around class, and can love and happiness co-exist with that? And in Eastern Europe, there’s much less of an idea of: I will shape my destiny. It’s like fate will come in and toss me around and send me in every direction, and let’s see if I can survive it.

Because that’s very true in my family’s lives: wild swings of fate, extremely close calls, huge moves of thousands of miles back and forth, death and exile. Exile is pretty much a part of people’s lives, huge moves.

And a defining thing in Eastern Europe is people changing the nation they’re in, changing the empire they’re in, without moving. You know, Uzhhorod in now western Ukraine – people who lived there switched the state they were in, the nation they were in six times, just in the ‘30s and ‘40s without moving at all. So your passport’s changing, your identity card’s changing without you doing anything, it’s out of your control. There’s so much in life in the 20th century that’s out of your control.

And I think the war in Ukraine has brought a lot of that feeling back. Because things are pretty good in Poland, but that feeling of unsettlement and unease, and I wonder how much that’s true in the Baltics – that the bad days could come back.

Oh, I think 100%, yeah.

We were talking about Eastern European fiction, and it’s quite obvious from the book there’s a real passion and delight in – well, the culture of the region in general – but I think especially the literature. It prompted me for example to go back to the [Hungarian] writer Gyula Krúdy, who I think is a wonderful writer and I read a long time ago, so that was a wonderful rediscovery.

Could you highlight any writers or artists who you think deserve more attention? Because I think this is one of the issues with what we were talking about – the fact that there are so many countries, and the languages are so inaccessible for many people, that so many people are ignored who don’t deserve to be.

I think Gyula Krúdy is a great one – he’s kind of untranslated, or at least we’re just kind of on the top of the Krúdy iceberg with what’s in English, so I’m excited to see more of that come into print. He’s kind of an effortless… he could write 16 pages in a tavern every day, and then go and gamble and carouse and spend time in a brothel. He had that kind of natural gift that Jaroslav Hašek had too, the same kind of era…

They’re always about food, aren’t they?

Lots of food, lots of drink.

At least his short stories are – they always seem to start or end in a bar, which I enjoy very much.

I love a Hungarian tavern. On kind of the opposite emotional end, Ismail Kadare is someone who I think is pretty well-known, but I’m always championing – he’s always my pick for the Nobel Prize. I’m hoping Kadare gets it before it’s too late [this interview was conducted before Kadare passed away in July 2024]. An Albanian writer who continues to write – who has a fascinating gift for allegory and for finding universal historical moments. He writes these books that are sort of set in the Ottoman Empire, kind of an Ottoman Empire of dreams. I think the best one is The Palace of Dreams, in which he imagines a kind of secret police that investigate people’s dreams.

Dreams say so much about people’s lives, and transforming the experience of Albanian Communism to this slightly magical realist but also very grounded and very compelling mirror-world. I really like him. Very easy to read also.

Just a comment on that – I’m reading at the moment actually Broken April [by Kadare], which does touch on some of the things you were talking about. I don’t know how far that reflects life in the Albanian mountains, or how far it ever did. There’s the kind of honour code, which in a way seems to be an example of something you talk about in your book: these very specific – maybe not ethnic groups, but cultures that develop that are very kind of unique and unusual on a European level.

You know, I was in Albania, northern Albania, and apparently honour code killings were really bad in the ‘90s into the early ‘00s. And now it’s really settled down, but there’s still a trace of it. But I was in Shkodër and I was shown an apartment building. In the high mountains, you can go and see these kind of towers of silence, where if you were under ban, if a clan had it out for you – a rival clan, to kill you – there were places you could go for refuge. Back in the old days, If you stayed in the tower, no one could touch you. And in Shkodër, which is a modern city, there is an apartment building, which in the ‘90s people could hide out in. As long as they stayed in this apartment building, they weren’t under the mark of the honour code, but if they left, anyone in the rival clan could kill them. So that persisted I think to the very recent past, I think now it’s pretty much almost gone. I saw a magazine story, talking to the last people under that indictment. But apparently Communism put a lid on it, and then in the ‘90s it kind of exploded, so it’s still in people’s experience. I love Albania, I love travelling there. It’s so interesting.

Miklós Bánffy – that’s The Transylvanian Trilogy. It’s really Tolstoyan, sweeping, multi-character – politics and romance. That kind of novel with a capital “N”, vast, generational, extremely well-written, extremely compelling, and an extremely great tapestry of specifically Transylvania in the years leading up to World War I. Reads wonderfully, it’s a great summer read, if you’re going to the beach and you want to read for a week straight.

And he was actually a very wealthy Transylvanian aristocrat – one of those Hungarian families who were rich in Transylvania. He was a statesman; he shows up in my book doing the coronation ceremony for the last Habsburg emperor, which was very short and not very dignified – the Hungarian coronation. But a wonderful novelist, people periodically rediscover him. Especially if you have been to the area, it’s very true to specific places in Transylvania. It reads wonderfully.

Bruno Schulz is my first favourite, my first love.

I love Bruno Schulz.

I was actually named for Bruno Schulz – my first name is Bruno, my full name. And I’ve been fascinated by him my whole life. And going to Drohobych [now in western Ukraine, in Poland between the wars], going to where he was from, as part of the research for this book was one of the great experiences of the book. Because so much of Drohobych is just there and it hasn’t changed that much, and hasn’t either been memorialised, so you’re in a modern Ukrainian town, but you can feel everything, because the houses are still there, the mansions are still there, the streets are still there. The Street of Crocodiles, you can actually walk along it. You have this amazing kind of teleportation.

It’s a town where both everything has changed, because it used to be a very Polish, Jewish and Ukrainian town, and it’s not Polish or Jewish anymore, and in some ways nothing has changed, because it really wasn’t touched in the war – physically, most of it; none of it was burnt down – it just kind of has gotten weatherbeaten over the years. I printed out a guidebook, and you can go house-by-house to see where Schulz lived, where his lovers lived, where he taught, and where under fictional guises the different buildings are, it’s all there for you to see. And kind of no one cares, because it’s provincial Ukraine, and this is a Polish-Jewish writer who they have an ambivalent relationship to. So you can just slip through time in an amazing way.

Well, that’s another one of the questions, isn’t it, in the book, which I think is too complicated to get into in a lot of detail, but the question of nationalism, which results in a way from the fact that the region is so diverse. It’s often perceived that Western Europe invented nationalism. Do you think there’s a difference in the Eastern European form of nationalism, if we can generalise that much? Because one of the common features is that those countries mostly did get their independence at around the same time, from different empires.

You talk about how for example in the Czech Republic, you had this attempt to find The Judgement of Libuše, these ancient Slavic texts which were discovered to be fraudulent. I mean, you do have similar examples in Western Europe, don’t you – cases like Ossian, the Scottish bard. Is there a difference, or is it just later?

I think there is a difference. And actually I think there is a difference which has a commonality with the Celtic part of Europe, because Ireland had a similar nationalism. But a nationalism in Eastern Europe that starts with culture, starts with language, and sees that as the initial thing to cultivate, and then progresses on to having a state, instead of having a state and trying to inculcate culture.

In France, there’s a state for hundreds of years, and it’s only really in the 19th century when they start trying to forcibly teach people: “you are French, you should be a patriot of France and speak the French language, rather than Occitan, or Auvergnat, or Breton”. They start to push that, and to nationalise their people. In Eastern Europe, almost always it’s the reverse – of “we have to kindle our language, revive our language, revive our culture, and once we have built our cultural and linguistic unity enough, then we can aspire to statehood”, so the direction is different.

And I think specifically with that example of Ossian, the Celtic part of the British Isles has some of that same pattern – the Welsh, and the Irish, and the Scottish – of language, culture first, reviving and restoring in the 19th century and then aspiring to autonomy or nationhood. There’s a way in which Ireland has a lot in common with Eastern Europe. But then it kind of skipped the whole 20th century, being in the wrong place. But that sense of language being so important, culture being so important; it has two politics. Rather than politics in a country like Germany – German unification happens and then you try to make a more uniform, state-centred, civic patriotism around that and to nationalise that. So the order is a little different.

So I think the pattern is distinct in most of Eastern Europe – and the timeline is distinct too, because you start with these national movements. You start with really small cultural, literary movements that turn into political movements that turn into countries eventually. Very different from what happened in most of Western Europe.

On the subject of nationalism and the result of empires, there’s decolonisation, which has obviously been a very popular concept – in different places and at different times, but it feels like especially now, for various reasons, in Western Europe and America.

I saw a very interesting tweet some time ago, maybe about six months ago, by an Estonian – I would have to look up his name, but I’m sure I could find it for the interview. He seemed sympathetic, but he said for an Eastern European “decolonisation” is very confusing. Because when an Estonian is told: you need to decolonise your university or you need to decolonise their studies, he said that could apply, to his mind, to three things: it could mean the Russian Empire, it could mean the Soviet Union, which generally is not at all what people in the West think of in this context, he said it could even mean kind of local nationalist understandings, which are obviously very powerful.

I was curious if you had any thoughts about that, if that’s a useful framework that can apply for Eastern Europe, or is it just so different that it’s its own thing?

That’s fascinating, and I’ve seen this too, in a Polish context. I think the decolonisation framework is both useful and misleading. It definitely has a lot of purchase – and decolonising is used in different ways, and it’s been taken up especially by the university crowd, I don’t think it’s quite like a popular political thing. But if you study history and culture, you find it has a lot of purchase across the area, the framework.

And yet I also think, like that tweet says, it can be misleading because the frame is so different. Much of Eastern Europe in a sense was colonised, or all of it was part of empire – but also a lot of these nation-states that emerged did their own colonising, so to speak. So is the idea to decolonise yourself from an imperial heritage, or to decolonise to make up for your own treatment of minorities? And there’s a vast space between those two.

There’s a way that perspective on decolonisation allows a lot of the countries in the region to centre their victimhood, their sense of having been wronged – an often very justified sense – but what I would hope it would do is that also the framework of decolonisation would lead people in essentially every Eastern European country to reflect on what a national mission or a national frame has done to persecute or exclude people within that. You have that double of victimisation and victimising, which runs through the national history of almost every country in the region – most are victimised by some larger imperial power, and have done victimising to their own recalcitrant minorities. And I hope that it allows not just a sense of “we, the victims” but also “oh no, we have things to atone for” – that both are brought out in that framework, and I’m not sure that’s always the case.

And, you know, this is the part of Europe that didn’t have overseas colonies – except for, I know, a very small Latvian exception. But that is a very obscure point.

Saying Latvian I think is also very misleading – it was basically a German [German-run state]…

I understand. That’s a strange little – and to me very interesting – footnote. Because it gets roped in under Poland’s only colony.

I think that’s a bit misleading – because Courland was really a vassal state. It wasn’t really part of Poland-Lithuania in any meaningful sense.

So every part of that is kind of not what you think it would be. So that’s again where that framework of decolonisation… the further back you go in time, the terms – nothing is ever quite what you expect it to be. So that’s actually a great example.

I was surprised that you have monuments to Jacob Kettler – there’s a monument to him in Kuldīga.

Connected to talking about writers you think you deserve more attention, you’ve obviously travelled a lot for the book – you said you didn’t have the chance to go to Moldova or Belarus, but it seems you went more or less everywhere else during the research process. I was wondering if there was anywhere you would really highlight as deserving more attention, more visitors.

Just a personal note, last summer I spent a few days in the Danube Delta in Romania, and I remember thinking – I’ve travelled a lot in Europe but this is genuinely one of the wonders of Europe, and if this was in Italy, I think it would be absolutely flooded with tourists and everyone would know about it. And we were there for a few days and I think I barely heard anyone who wasn’t speaking Romanian – there were tourists, but they seemed to very much be local tourists. I don’t know if you’ve been there, but I think that is just an extraordinary place. And again, I think the reason it’s not known is because it’s in “eastern Europe”.

Did you stay in Sulina?

Yes, we stayed in Sulina, but took a few boat trips around, and went out to Sfântu Gheorghe as well.

I had that on an itinerary and I had to cut it short. I went to Babadag, which is on the way to the delta and then I had to turn around.

In terms of places, I’ve written about this for The Guardian: Albania, I went all around Albania and it really knocked my socks off. I think it has more and more visitors, but both the south and the north are so different, getting away from Tirana, are so spectacular. It’s physically spectacular, the history is so intriguing and kind of well-curated. They have wonderful museums all around the country, you can really get a feel for different periods of history, different local traditions. And it has a little bit of that Eastern European… part of the diversity is that it’s still a generally multi-religious country – it’s simultaneously Muslim, Orthodox and Catholic, all in one place. It has a little Jewish heritage too. And that’s all very much alive and present.

I just think it’s enormously rich as an area to visit. And I especially recommend the northern mountains or Gjirokastër, where Kadare was from, a city near Greece – very distinct in its architecture and its incredible stone houses that have been there forever.

There are so many places. I’ll say I think an area that’s not well known: eastern Hungary. The area around Tokaj is a fabulous place to visit – the part of Hungary near Slovakia, near Ukraine. Fantastic food, fantastic wine, beautiful volcanic hills that also look like they’re in Italy, covered in vines, but also far away from everything. There’s this village called Mád in the Tokaj wine country – fabulous old synagogue, fabulous working vineyard, parts of the Calvinist and the Protestant Hungarian heritage there too. It’s a wonderful little hidden, multicultural Tuscany, tucked away next to eastern Slovakia, which is also very interesting.

But I think especially British people know more – Transylvania’s on the map. There are a lot of places in Poland I’d recommend. But that’s a great, very unknown destination, I think – the Tokaj area.

The question I wanted to finish on because it’s connected to the future. One thing that occurred to me when reading the book is that in a way – maybe you even mention this, I can’t remember – Eastern Europe as a concept is kind of inseparable from the idea of failure. And there are aspects of that that are very pleasing; as you say in the book, the reason that it’s so diverse and interesting for many people – definitely including me – is because the empires were quite unsuccessful at enforcing their language or their religion or whatever it was they wanted to do. So that in a way results from a kind of failure – they were less effective states than a country like France, for example – or maybe in some cases were more tolerant, but I think in many cases were less effective.

And then something you’re certainly conscious of, living in the region now and travelling, is that Eastern Europe is used less as a geographical descriptor as an identity that people kind of assume or are branded with – whether by themselves or by other people – when they’ve failed to achieve something. Eastern Europe is something people want to get away from, and they want to prove that they’re Northern European or Western European or Central European, in some areas. And if you ask people where you are, Eastern Europe almost doesn’t exist.

That’s quite a commonplace observation in a way and lots of people notice that. But now, as you describe, the region – or at least the part of the region in the EU – is becoming basically quite prosperous, and we have all these horrified headlines in the UK, which I think is the country in Western Europe that’s had the worst decade, about how in five years or ten years we’ll be poorer than Poland or Slovenia – it’s always an Eastern European country chosen to be the self-evidently horrifying development. Do you think that can ever change? Do you think Eastern Europe can ever be seen as something positive, a success story? Or is it always something people will want to get away from? Quite a long question, I know.

Geography is difficult. It’s an interesting question because part of what I’m describing is Eastern Europe escaping its easternness. Poland and Slovenia and the Czech Republic and Estonia, and actually a lot of the region, are increasingly hard to distinguish from the West. It’s hard to distinguish when you’re there, especially in metropolitan centres – the quality of life, the texture of life, economically, they’re converging on the West. And yet the idea of the East is a little separate from the actual condition.

We were talking about the psychic weight of being Eastern European, and of fragile statehood. I think just that term “east” will continue to move east in where it’s applied to – east to Belarus, to Ukraine, to Moldova. And in those parts of Eastern Europe, that wave of progress of the last 30 years really hasn’t come about very much.

I think that’s also true especially in the Serbian part of Bosnia – in all of it, but especially the Republika Srpska. There are places where you feel that the 1994-95 war ended weeks ago: just burnt-out villages, villages where trees are growing inside ruined houses, and the conflict is frozen in place. You have a lot of frozen conflicts on the peripheries of Eastern Europe.

And I think that idea of “east” will migrate and attach itself to those areas, the places that are frozen in time in one way or another. Belarus has a government that feels like it harks back to an older era. Ukraine, Moldova – Ukraine much more than Moldova – are under a conflict that seems like it harks back, that keeps it from progressing. Parts of the Balkans – Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina – have an unresolved status that keeps them from moving on. So Eastern Europe will kind of drift towards that area.

I don’t think we’re close to it fully flipping, like what Ireland has done – from a certain kind of periphery to a certain kind of centre, you know, the Celtic Tiger. I have less of a feel for this, as an American – but there are certain moments when a periphery can become its own centre. I think with Eastern Europe, the periphery keeps becoming more peripheral. And we’re not at a point where we can just flip it.

And there’s a way in which… is Russia part of Eastern Europe? It’s not part of the Eastern Europe I’m describing, but it’s there in the east. And that’s such a big geographical fact and somewhat inescapable, that it’s hard to have that redefinition of values that I think you’re asking about.

Well yeah, because your book – although obviously lots of terrible things happen and you describe lots of the problems here, it does ultimately paint quite a celebratory image of Eastern Europe, or certainly a kind of justificatory image of Eastern Europe. But that’s a concept that inherently in the title you’re saying is going to die. So it’s an interesting concept.

Exactly. I mean, the 20th century did so much damage, brought so much destruction on that multicultural, religious heritage.

And now prosperity is having its own kind of dissolving effect on distinctiveness, which is positive in a way, but also means that in a lot of Eastern Europe its qualities are vanishing. Actually, you know I find that much more in Lithuania than in Poland, when I go there. I’ve spent a lot of time in Lithuania. I think maybe it’s the amount of rural flight in Lithuania and in Latvia, which is different than in Poland, where you go into the villages and you also have that sense of stepping through time. Whereas in Poland, everything is being torn down and rebuilt, and the rural landscape has just been completely transformed and rebuilt, and it’s much less true, I find, in rural Lithuania. Sometimes I’m like “oh, this is like stepping into the ‘50s or the ‘80s” I think, because the economic balance, the population balance is different.

But ultimately, the arrow is towards homogenisation in most of the region. And I think that’s true of modernity everywhere, in a way – it homogenises as a force, which is both positive and negative, but inevitably involves some kind of loss.

*“That value could simply evaporate shocked eleven-year-old me. The idea that you could prepare for the future appeared then as yet another Eastern European mirage. Now it seems merely to sit at the end of a long line of family losses: the estates somewhere in western Lithuania, the brownstone in Warsaw, a fortune in German marks kept somewhere near Poznań, and my great-grandfather’s butterfly collection, turned into a fine yellow dust by a bomb in the First World War. All seem contained in that blue tin box. To me, it symbolizes not just the era of transition but the capriciousness of history itself.”

Goodbye Eastern Europe is available now from Oneworld. You can find out more about Jacob Mikanowski’s work on his website.

© Deep Baltic 2024. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.