Industrial heritage in Estonia and Latvia

Industrial heritage is part of our cultural patrimony. It provides evidence about the development of industrial technology, and changes in working methods and conditions, and helps us to reach a broader understanding of history and the development of society.

The oldest preserved examples of industrial heritage in Estonia and Latvia date from the 18th century when Estonia and Latvia were within the sphere of imperial Russia, and large-scale industry and land, along with special rights, had been concentrated among the Baltic German aristocracy. In the countryside, rights and opportunities to work with business were in the hands of the landed nobility, while in the cities it was the guilds and corporations who had this position.

After the abolition of serfdom and granting of the ability to purchase land in the 19th century, the people were able to freely change their place of residence. Cities and industry grew quickly. Thanks to their favourable location, in Estonia and Latvia there appeared huge industrial enterprises, oriented to the Russian market, which at the time were the very biggest in Europe.

First of all came textile and paper factories, then beer breweries and vodka distilleries. At the end of the century, manufactories became more productive with the arrival of steam-powered factories; machine production, metallurgy and other fields of industry appeared.

The development of industry was encouraged by the railway lines built in Estonia and Latvia between 1860 and 1870, which connected the ports there with Russia. Construction of a large-scale railway network began. Along with the broad-gauge railways there also appeared narrow-gauge railway lines built with private capital; the construction and exploitation of these lines was less expensive and they addressed the need for regional transport for goods and passengers.

By steam-powered factories and railways, water towers were built, which supplied the steam-powered machines and engines with water. At the start of the 20th century, water towers were also erected in cities and on country estates in order to provide water for drinking and fire-fighting.

Shipping on the Baltic Sea also lay within the Russian sphere of influence, and at the turn of the 20th century, many new lighthouses were built along the Estonian and Latvian coast. Together with masonry lighthouses, there also appeared slender metal lighthouses, assembled onsite and produced in France and Britain, which used the most modern paraffin-powered optical equipment.

Tallinn became the fourth-largest port in the Russian Empire by turnover of goods, while Riga became the fifth most populous city.

The high level of education, and the acquisition of property and skills in manual labour also encouraged entrepreneurship and national consciousness among the indigenous inhabitants of the region – Estonians and Latvians – and various small businesses, windmills, and limestone and tar kilns appeared.

After the First World War, Estonian and Latvia achieved independence, and educated and entrepreneurial Estonians and Latvians became the main drivers of the economy. The huge Russian market disappeared. Only the textiles and cellulose industry had the ability to adapt, and in place of enormous factories there appeared many smaller productive businesses. On the strong agricultural base, food industry developed, gaining a significant position in exports.

This industry was supported by high education levels and also received support from the state. New and innovative inventions became available. For example, the wireless sets produced by the Riga factory VEF and miniature Minox cameras were exported to Europe and America. The Minox camera could fit in a waistcoat pocket, and these “James Bond” cameras are still produced today, although they are now made in Germany and are digital.

In Estonia and Latvia there can also be found exciting examples of architectural heritage from the Soviet period.

Industrial heritage tourism is a growing trend, and a good opportunity to preserve and get to know old industrial buildings and technology, and the skills needed to use them.

Ristna lighthouse

Ristna, Estonia

On the west side of Hiiumaa island, not far from Kõpu lighthouse, stands the red-painted Ristna lighthouse. The lighthouse is made up of two iron cylinders slotted together, between which wind spiral steps. The lighthouse is distinguished by its eight sculpted supporting pillars, as well as by the outward-facing service room, five metres in diameter, above which is the lantern. Next to the lighthouse there is a small eatery.

The nearby Kõpu lighthouse is often wrapped in fog, and so it was decided to build a new lighthouse at the end of the Kõpu peninsula. This lighthouse had an additional task: to signal with its red flashing light about ice movement, if there was any such movement in the Gulf of Finland that would obstruct shipping. During the First World War, the lighthouse’s fragile supports were seriously damaged, and in 1920 a concrete base was built around the lighthouse.

Iron construction lighthouses were significantly cheaper and quicker to put up than the hardy cast-iron Gordon-type cast iron lighthouses, because they needed less time to assemble and iron was more cost-effective as a construction material.

In 1884, a 20-pood (328-kilogram) fog bell was installed at Ristna lighthouse. A year later the existing optical equipment within the lighthouse lantern was fitted out with a clock mechanism and gravity-powered revolving covering screens, which were set in motion when there was moving ice in the Gulf of Finland. In 1889 near the lighthouse an iron-tin outbuilding was constructed, in which was installed the first steam siren in Estonia.

Räpina paper factory

Räpina, Estonia

In the south of Estonia, alongside the Räpina waterfall, can be found Estonia’s oldest – and still-functioning – paper factory, whose main building is one of the most unique examples of industrial architecture in Europe.

Accompanied by a guide, you can familiarise yourself with the history of the factory and the process of paper production, both in the distant past and nowadays, as well as about the technology and equipment. Here there function fleets of both old and new machines alongside each other. Fondly nicknamed “old man”, the oldest parts of the steam cylinder machine, manufactured at the Sigel factory, were produced in 1860.

On the excursion, visitors are led above the huge basins for paper pulp, by a separator, and are shown how water is forced out of the pulp. Among other things, products are made from recycled paper money, now out-of-circulation Estonian kroons and Finnish markkas.

The history of the paper factory stretches back to 1728, when Count Karl Gustav von Löwenwolde, a courtier to Tsar Peter I, decided to use the powerful flow of the River Võhandu for industry. From bricks produced onsite were built a sawmill, flour mill and paper mill.

The paper mill began work in 1734, and flax rags were used for the production from repeatedly processed raw materials.

In 1865, the paper mill became a factory. The first paper-making machine was received from Germany, followed quickly by three others. The factory started to make especially thin sorts of paper such as filter paper for pharmacies, blotting paper, cigarette papers and tissue paper.

These days the factory is modernised and produces a wide range of edge protectors, wrapping paper and other paper products made from reused material.

Railway and Communications Museum

Haapsalu, Estonia

Visitors are greeted by a courteous 1930s station-master, and it’s possible to take a look into the station post office.

The Railway and Communications Museum can be found in the Haapsalu station building, a historicist-style structure decorated with wood-carvings, and the surrounding grounds. There guests are led on a journey back in time through Estonia’s railway history.

The station building has an unusually long platform (213.6 metres). Evocative scenes of station crowds and the whistles of steam engines can be revived by a modern means: pressing a button. The rolling stock includes steam and diesel engines, carriages and pump trolleys. On the site a water tower, depot, turntable and residential buildings for railway workers have been preserved.

The railway station building was constructed following an original design at the start of the 20th century, along with the Haapsalu-Keila section of the railway, and is grander than the other stations, allowing for the possibility that the Russian Tsar and his family might turn up. At the station there is an imperial pavilion, and a large summer buffet space. The spa town of Haapsalu was a favourite summer getaway for the Tsar in the summer, and the Tsar himself apparently supported the construction plan and helped to make it a reality.

The first train arrived in Haapsalu in 1904, and the last in 1995. From the station it’s possible to take an introductory tour around the city with the little train Peetrike.

Lasva Water Tower Gallery

Lasva, Estonia

In Lasva at the edge of Võrumaa a water tower decorated with a Rõuge folk pattern has received a design award, and functions as a gallery and a regional cultural and tourism centre. On the walls of the tower an exhibition has been installed in order to familiarise guests with the region. To enable visitors to get from one floor to another, a unique set of “piano” stairs has been created. Every step taken while on them creates a new world of sound. From the tower roof, which is covered with greenery, a beautiful view over the vicinity is revealed, and it’s a spot that’s just made for picnics.

Zilaiskalns Water Tower

Zilaiskalns, Latvia

At the foot of the hill of Zilaiskalns can be found ZTornis, the Zilaiskalns cultural history and visitors’ centre, which is situated in an old water tower and the adjacent modern buildings. Zilaiskalns water tower is an Art Deco-style building which in earlier times supplied the village and the peat production site with water.

At ZTornis, you can take a look at a historical exhibition about Zilaiskalns, which is both a natural attraction and a sacred site, as well as the settlement of Zilaiskalns, and the water tower – an example of industrial heritage. With the help of virtual reality, visitors have the opportunity to look at Zilaiskalns from above and take a look inside the historic narrow-gauge locomotive.

After visiting the water tower, guests can get on a rail bicycle and pedal two kilometres along the old narrow-gauge railway track. The rail bicycle has been adapted so four people can use it simultaneously.

Flat for Līgatne Paper Factory Workers

Līgatne, Latvia

Līgatne is a settlement built for the workers at the oldest paper factory in Latvia, and is a unique and unified industrial heritage ensemble.

The flat is located in one of the unique houses of the Līgatne paper factory settlement, made up of wooden buildings and constructed at the end of the 19th century. The factory’s paper mill was established here in 1815. The paper factory needed workers, while the workers needed a place to live. And so was created the now 200-year-old workers’ settlement, which has preserved its original appearance to the present day.

A walk through Līgatne leads visitors through all of the life stages of the paper factory’s workers. The buildings which can be viewed here were at one time the hospital, the maternity house, and the school for the children of the paper factory workers, as well as terraced houses with little gardens alongside. For each group of three terraced houses there was a utility building known locally as “the brewery” where clothes were washed, bread was baked and meat was cured.

One of the flats has been restored to its former appearance. In this authentic environment, you can put a kettle on the fire, and through the medium of video travel back a century into the distant past in order to take a look at the everyday life of this family.

Eisenstein Communication Centre

Ķeipene, Latvia

Ķeipene is referred to as Latvia’s capital of cinema history. Ķeipene railway station was opened in 1937, during the construction of the Riga-Ērgļi line. The current station building was constructed in 1950. During the process of closing the line, the tracks were pulled up in 2009, and Ķeipene station is the only place on the Riga-Ērgļi route where they remain.

Now the only publicly accessible exhibition in the world dedicated to the director Sergei Eisenstein, a giant of cinema, has been created here. During the Arsenāls cinema festival in 2000, a “dry-land” lighthouse was constructed with a light for air navigation alongside the Eisenstein Communication Centre, as well as 66 postboxes dedicated to cinema pioneers and a five-metre-high table with two chairs for giants of cinema. The table can also be used as a viewing platform. In the station building, where an exhibition focuses on Eisenstein, there’s a retro telephone which gives a rare opportunity to “call up” cinema stars. It’s also possible to send postcards with greetings to your favourites of world cinema – to the address: Dzelceļa stacija (Railway Station), Ķeipenes pagasts, Ogres rajons, LV-5062.

Over the tracks stretches a tunnel made from 24 film frames, which is dedicated to the first cinema reel. Underground an environmental installation has been constructed – an eight-metre deep and four-metre wide “Potemkin well”, which has been created as an exhibition room under the ground, focusing mostly on Battleship Potemkin.

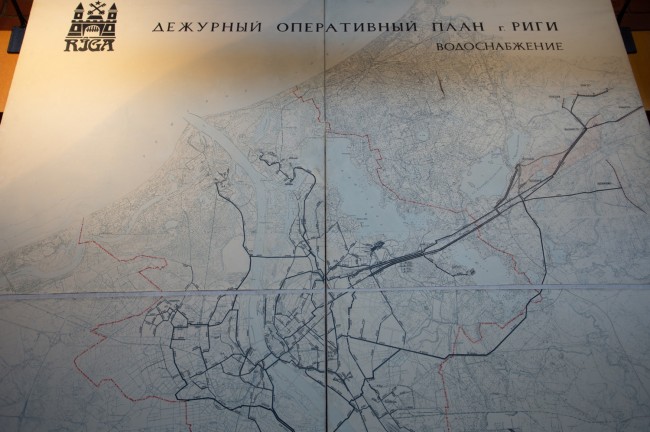

Riga Water Supply Museum

Ādaži, Latvia

Located in Ādaži since 1988, this is one of the most significant water supply museums in Europe. It provides historical evidence about the four-century-old water supply system of Riga, whose origins can be traced back to the 17th century. That was when a horse-powered pumping station and a system of wooden piping was built, through which city-dwellers received water straight from the River Daugava. By the end of the 19th century, this system no longer satisfied the needs of the growing population, and it turned out that water from the Daugava did not meet the standards for drinking water.

In 1883, studies were carried out and large concentrations of good-quality groundwater were discovered in Bukulti, as well as in the area of Remberģi and Zaķumuiža. The construction of a system for obtaining groundwater was started within the grounds of Bukulti manor, as was the construction of a pumping station by Mazā Baltezers Lake, as well as piping for transporting the water to Riga.

The Baltezers pumping station started work in 1904 and continued functioning until 1950. Today, the Riga Water Supply Museum is set up in the machine room of the old pumping station. The Compound-brand steam engines have been preserved, as have the syphon tubes and pressure mains produced at the Felser machine factory in Riga. The boilers were produced at the R. Pole machine factory in Riga.

Texts and images provided by Industrial Heritage for Tourism

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.