by Agris Dzenis

No Baltic tribe or tribal group seems to have had a history so dynamic, rich in incident and tragic as the Old Prussians. They died out during conflicts between two medieval European cultures – Christian and pagan – and were physically destroyed or assimilated. The Latvian and Lithuanian people have the Old Prussians to thank more than anyone else for their existence. Under the cover of their heroic resistance against the crusaders, which lasted for almost the whole of the 13th century, the foundations of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were laid, which, in turn, became an obstacle to the mass inflow of crusaders and German colonists into the territory of Latvia.

The Old Prussians belonged to the Western Baltic group of tribes, which also included the Curonians, Samogitians, Skalvians, Galindians and Yotvingians. Around 3000 years before the birth of Christ, the Old Prussians broke away from the first Indo-European peoples and entered the land where they would live right up until their eventual disappearance. Today the area where the Old Prussians lived is divided between Russia (the province of Kaliningrad) and Poland (the provinces of Elbląg and Olsztyn).

The 1st-century Roman historian Tacitus’s work Germania was the first text to mention the Western Balts. Tacitus called them as “Aesti”, which means “easterners”. This was also how their western neighbours, the Germans, referred to the Balts. The Aesti were described as industrious farmers and peace-loving people. They collected amber from the seashore, and, as to them it seemed worthless, they were astonished at receiving payment for it. In fact, it was amber, which in ancient Rome was valued more highly than gold, that brought the regions inhabited by Balts to the attention of the civilised people of Europe. The region that was the richest of all was the region inhabited by the Old Prussians – Sembia (now the Zemlandsky Peninsula in Kaliningrad). From the lands of the Balts, amber arrived in Rome, mostly through German intermediaries. In exchange for these “stones of the sun”, the Balts received iron, weapons, Roman coins and jewellery. At the start of the common era, one Roman of noble birth travelled, with his retinue, to the regions from where the amber came, and brought back so much that the gladiatorial arena and the fighters’ weapons were decorated with jewellery.

The Prussian word “Precun” appears for the first time in a 9th-century text, along with other Old Prussian words: “Pruzzi”, “Brus”, “Borussi” and “Brutheni”. The 11th-century chronicler Adam of Bremen characterised them as very humane people (“homines humanissimi“), who often saved seafarers from shipwrecks and pirate attacks. The Prussians would not accept any among them being a master over others, and regarded as worthless furs, gold and expensive cloth.

The Old Prussian tribes inhabited eleven regions (in the Old Prussian language, “tautos“), whose names are mentioned in writings from the 13th century: Semba, Nātanga, Nadrava, Pamede, Vārme, Bārta, Skalva, Sudāva, Galinda and Kulma. Modern historians do not include the Skalvians, Sudavians or Yotvingians, or Galindians as Old Prussians, but consider them separate Western Baltic tribes. Each region was governed by a ruler and an assembly of respected nobles. The Old Prussian lands together formed a federation of tribes, and in cases of war would usually work together, although instances of internal conflict within regions were not infrequent.

According to an Old Prussian legend, the first leaders were two brothers, Prūtens and Vudevuts, who arrived, together with many others, from overseas in the old times. Vudevuts was elected as the the krīvu kirvaits: the Prussians’ highest earthly leader, an intermediary between gods and humans. The krīvu kirvaits, also known as the krīvu krivs, is mentioned in many old texts, and the Teutonic Order chronicler Peter of Duisberg wrote that the krīvs was obeyed not only by the Prussians, but also by other Baltic tribes, in the same way that the Christian peoples obeyed the Pope. The krīvu kirvaits’ seal was a crooked stick – a krivule. This seal was carried also by the krivs‘ messengers, who were sent all over the Old Prussian lands to notify the people of the high priest’s orders.

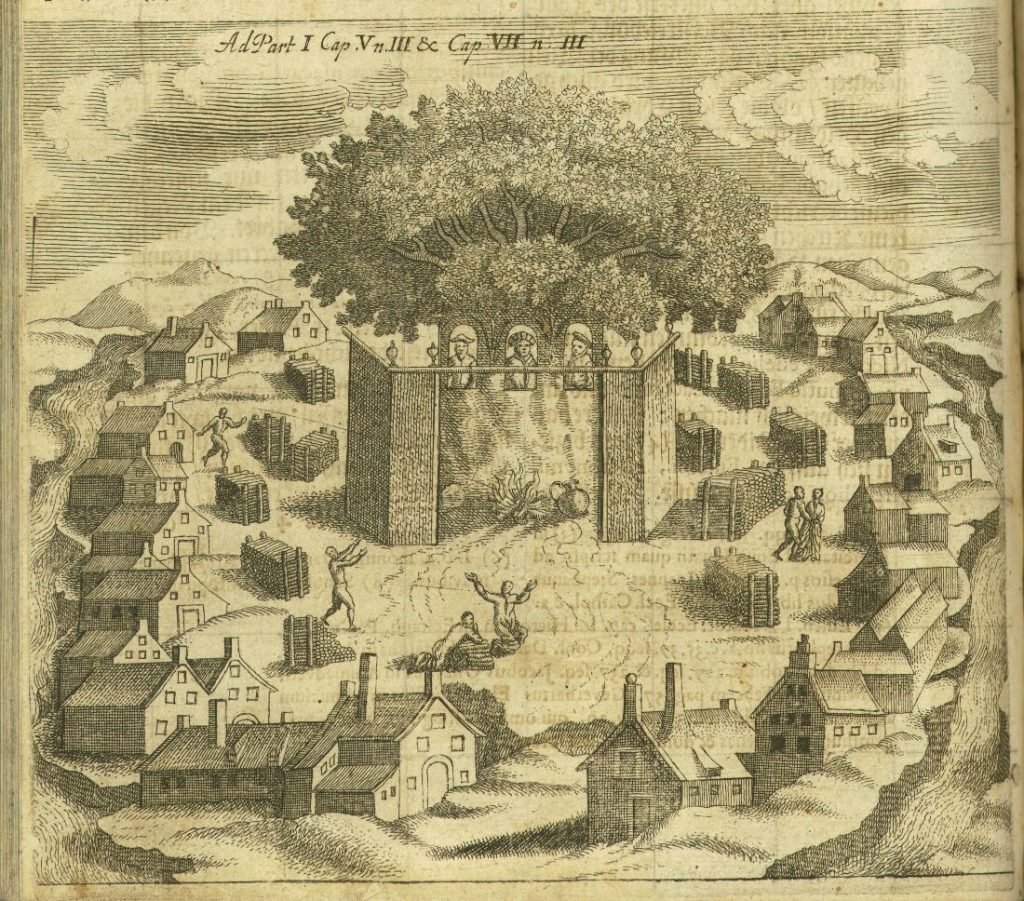

Prūtens ordered the Prussians to pray to and pay homage with sacrifices to the three high gods – Patrimps, Parkuns and Patolis. Images of these gods were placed into the hollow of a huge, evergreen oak tree, which grew in the main holy place of the Old Prussians, Rāmava or Rīkoita in the region of Nadrava. In Rāmava lived the krīvu kirvaits himself, and here also met the Prussian nobles who decided all of the most important questions facing the people. It should be noted that place names with the linguistic root “ram” are found in all of the Baltic countries (in Latvia, there are Rāmava, Rāmuļi and Rāmnieki), which makes us think that the word “Rāmava” (“place of peace”) was generally used to indicate a place holy to the Old Balts. Details of the sacred groves of the Old Prussians can be found in a number of chronicles. These were places where people neither cut down trees, nor mowed the grass, nor hunted animals; people were not even allowed to go there without making a sacrifice to the gods. National meetings, in which decisions were taken about questions of war and peace and criminals were judged, also took place in the sacred groves.

The Old Prussians were allowed to make sacrifices to the three high gods only in Rāmava. Patrimps was the god of youth, fertility and good fortune, and was portrayed as a joyous youth wearing a wreath of ears of corn on his head. His image was placed in front of a pot filled with live grass snakes. Parkuns was the god of natural phenomena and justice, and was portrayed as a stern middle-aged man with a crown of flames. In front of his image burnt a sacred flame, which was kept going day and night. Patolls was the god of death and the underworld; he was presented as a deathly pale old man with a shroud wrapped around his head. In front of his image were placed the skulls of humans, horses and cows.

Patrimps, Parkuns and Patolls’ appearances and roles relate to the three main processes in nature and human life – birth/growth, maturity, ageing/death. The unceasing repetition of these process acts as the engine of the world, unceasing motion through changes. The origin of the engine was God – the creator of the world and the lesser gods – who was recognised by all the Baltic peoples, including the Old Prussians. They called God by the name of Deivs [in modern-day Latvian “Dievs” and in Lithuanian “Dievas”] and Ukapirmis (the First of All) and they viewed the light of the day as his visible manifestation. It’s possible that the Old Prussians did not pray directly to God, but through God’s sons – Patrimps, Parkuns and Patolls, to whom God had given authority over the world. Among the people, the most popular deity cult was that which took care of the important things in life – the fertility of the land, favourable natural conditions, good health, and success in farming and war. In ancient texts, there are many mentions of the lesser gods and mythical beings of the Old Prussians: Kurķis – the god of corn, who dwelt in the last sheaf of corn to be mown, just as the Old Latvian god Jumis; Aušauts – the god of health; Pilvītis – the god of wealth; Bārdaits – the god of navigation; berzduki and markopoli – house gnomes and spirits. Food and livestock were sacrificed to the gods; and to the higher gods were sacrificed a third of the spoils of war. The sacrifices were usually burnt on a holy fire in the sacred groves. At particularly difficult times for the people, such as war and harvest failure, humans were also sacrificed, most of whom were prisoners captured in battle. The chronicles mentions occasions when the Old Prussians burnt captured crusaders together with their horses and weapons.

In Old Prussian society an unusually great importance was placed on “spiritual intelligence” and on the high priests and priestesses. These were unmarried or widowed men and women who carried out the religious ceremonies – sacrifices, blessing the land and dwelling places. They were teachers, soothsayers, singers and seers of the people. Many of the priests – who were respected old widowers – would live together with the krīvu kirvaits in Rāmava.

Even as late as the 16th century, the chronicler Simon Grunau observed a high priest at work in a Prussian village. The high priest told the people of the village about the origins and gods of the Prussians, and gave ethical instruction, which the chronicler described as explanations of the ten commandments. The priest killed a goat to atone for the sins of the people of the village, which the Prussians then cooked and ate together. Assistance from these priests was sought even by the men of Christian countries. In 1525, the coastal territories of the Livonian Order were threatened by a large Polish fleet. The Order master turned for help to the famous high priest Vaitīns Suplīts, who killed a sow on the seashore, cast a number of magic spells and then threw the body of the animal into the sea. The Polish soldiers in the ships suddenly felt such a huge, inexplicable sense of fear that they did not dare make a landing on the coast. Not only that, but all the fish fled from the waters next to the coast, so that the fishermen were in danger of starvation. But after the priest returned to the seashore and performed some different spells, the fish came back.

When the legendary rulers of the Old Prussians Prūtens and Vudevuts had reached more than a hundred years of age, the Prussian lands were divided between the sons of Vudevuts; it is from them that each of the regions takes its name. Prūtens ordered the priests to choose a new krīvu kirvaits from among their ranks. Then, at Rāmava, both old men blessed the people one last time, urged them to honour the high gods, live in harmony with one another and protect the freedom of their people. Then Prūtens and Vudevuts willingly climbed on the pyre and were burnt as sacrifices to the gods.

The Old Prussians believed that through fire people and sacrifices reached the world of the gods. Archaeological excavations have shown that the Old Prussians burnt their dead together with their work tools, jewellery and weapons, which would serve in the afterworld just as they had in the land of the living. The ashes of the funeral pyre were frequently poured into a clay pot and buried in the earth.

The Old Prussians worshipped their ancestors Prūtens and Vudevutu as the gods Urskaits and Izsvambrāts (translated – the Elder and his brother). These gods gave benediction to farming, especially livestock and poultry. The Old Prussians put up stone images of Urskaits and Izsvambrāts to mark the borders of their lands.

The richness of “the amber lands” and their favourable position for trade on the Baltic Sea had long tempted unwelcome, armed visitors. In the middle of the 1st century CE, a conflict began between the Old Prussians and their southern neighbours – the Eastern Slav tribe the Masurians or Mazovians. The Masurian princes had tried to force the Old Prussians to acknowledge them as masters and pay regular tributes to them. But the Prussians held firm to Prūtens’ order to be loyal to their gods and their freedom. In the 7th century they routed an army made up soldiers of the Eastern Slavs and the powerful nomadic Turkic tribe the Avars. Some time after that the Masurian prince himself made a sacrifice to the Old Prussian gods at Rāmava. Among the Avar troops were many Prussian youths who had been captured while children during previous attacks on the Prussian lands. Before the decisive battle, they crossed over to their compatriots’ side, bringing with them a valuable new acquisition – the Avars’ knowledge of horseback warfare.

The Old Prussian lands were partly protected from Eastern Slav attacks by forests and a network of marshes, but it was not possible to put obstacles up against the invaders who came in via the Baltic coastline – the Scandinavian Vikings, who had started arriving in their boats, in search of both trade and plunder. There is a Scandinavian graveyard on the Semba peninsula by the village of Vīskautena, indicating that for quite a long time there was a Viking settlement there. Many attacks on Semba by Danish Vikings are recorded in 12th-century chronicles, although these attacks did not particularly threaten the independence of the Old Prussians, because their aim was plunder, not conquering territory.

After the Principality of Masuria joined the Kingdom of Poland, the Polish leader repeatedly tried to subjugate the Old Prussians as well. In the second half of the 10th century, Poland adopted Christianity. King Bolesław the Brave was the first to attempt to convert the Old Prussian lands to Christianity. With his support, in 997 the first missionary arrived – Adalbert, the Bishop of Prague. The Old Prussians realised that converting to Christianity could threaten their independence; they urged Adalbert to leave their land, but he did not obey and was killed. Before long Adalbert was made a saint, and depictions of his life made the word Prussian wider known in medieval Europe.

During the 12th century and at the start of the 13th century, the Old Prussians experienced repeated invasions from Polish armies. In 1218, the Pope declared a holy war against the Prussians, and crusaders from all over Europe started to join the Polish army. Their numbers originally were not particularly large, and so the Old Prussians managed to successfully repel their attacks.

The situation changed in 1226, when the Prince of Masuria, Konrad, summoned the Teutonic Knights to help him in his fight against the Old Prussians. The knights had been “unemployed” following the crusaders’ expel from Palestine. As repayment for their assistance, Konrad offered the Order the region of Kulma, which Poland had conquered. In that same year, the Holy Roman Emperor, Friedrich II, assigned the Old Prussian lands to the Order, and gave them the authority to subdue the inhabitants. The German knights tried as hard as possible to break deep into the interior of the Prussian lands; once there, they built castles, whose garrisons would regularly destroy surrounding villages and countryside in order to force the Old Prussians to convert to Christianity and recognise the authority of the Order. Despite tenacious resistance from the Old Prussians, the military strength was on the side of the Order, because they were helped by the armed forces of all of Europe. Increasing numbers of leaders went to the aid of the Order at difficult moments, hoping to find fame as a Christian knight and for rich spoils of war. So in 1255, the Czech king Ottokar II travelled with a large army to Semba through the Old Prussians’ southern regions. He took the Sembian castle Tvangste by the mouth of the River Priegle, and there he built a fortress, which later would become known as Königsberg [“king’s hill” in German; now the city of Kaliningrad in Russia].

The Old Prussians’ resistance against the crusaders was also hindered by a lack of internal unity. For a long time the different regions could not join together against a common enemy, and the Order also managed to get many Old Prussian nobles over to their side, allocating them the largest plots of land and thus preserving the nobles’ high social status even after Christianisation. The knights welcomed the nobles and the Prussians of lower status into their brotherhood, and they loyally served the Order. A register of the brothers of the Livonian Order from the 15th century includes seven Old Prussian names.

A number of peace treaties and truces were concluded between the Order and the Old Prussians, but the Old Prussians repeatedly took opportunities to rise up. A general Prussian rebellion started in 1260, after the German crusaders’ defeat at the Battle of Durbe. Old Prussians in the different regions chose military leaders and began coordinated acts of war. Many castles, which were significant points of support for the Order, were taken. The most significant Prussian leader was the Natangian noble Herkus Monte, who in his youth had been held hostage for a long time in Germany and had a good understanding of European warfare. The Order acted with unusual brutality in suppressing this uprising, completely destroying the dwellings of the rebellious Old Prussians and eliminating their inhabitants. With the help of a regiment of the Margrave of Brandenburg and the Czech king, as well as the defection of some of the Old Prussian leaders, the Order managed to subdue all of the Old Prussian lands by 1283. There was one last uprising in 1295, but it did not result in any particular achievements.

The conquered Old Prussian lands had become part of the state of the German Order. The chronicler Simon Grunau wrote that even at the start of the 16th century, several of the districts laid waste in the 13th century remained desolate and uninhabited. After their defeat, many Old Prussians had fled the yoke the crusaders’ yoke and escaped to Lithuania. Due to the resulting lack of labour in those regions ravaged by war, the Order settled many colonists from Germany there. However, it would be untrue to say that under the Order’s rule a process of Germanisation took place. In order to ensure the Prussians’ loyalty and to avert the threat of new uprisings, the knights had behaved in a tolerant way with them: the German colonists were allowed to settle only in the districts left barren by war, and the Order allocated the best land to the remaining Prussians. The Masters of the Order repeatedly emphasised that the Prussians must be allowed to stay Prussian, and they did not force on them the German language or way of life.

In 1525, the Catholic state of the Order became part of the secular Duchy of Prussia and Brandenburg, one of the first Lutheran countries in Europe. In the second half of the 16th century, with the support of the Duke of Prussia, three catechisms were produced in Old Prussian – significant testaments to this extinct language. Under the duchy, Poles moved into the western districts of Prussia, while Lithuanian farmers moved into the eastern areas – especially Nadrava and Skalva – and became intermixed with the Prussians. From the end of the 16th century, the parts of Prussia populated with Lithuanians started to be referred to as Lithuania Minor, which in later centuries became the centre of Lithuanian national culture. It could more accurately be said that rather than being Germanised, the Prussians were Polonised and Lithuanianised.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QriD_y92S4o&w=420&h=315]

In 1701, the Duchy of Prussia became a kingdom, and around the same time all of the rest of the German lands were united. The Old Prussian language disappeared for the most part after the Great Plague at the start of the 18th century, when almost all of the “pure” Prussians died. Their assimilated descendants instead wrote and spoke in German or Lithuanian. In 1871 a united German state was proclaimed and the Old Prussian lands remained part of the country, as the region of East Prussia, until the end of the Second World War.

At the end of World War II, the situation at the end of the crusades was repeated- the historic Prussian lands were occupied for a second time. This time this was not done by crusaders but by the Soviet army acting in accordance with the agreements made at the Yalta Conference. In 1946, the region of Kaliningrad was created, which still exists now. The German-speaking inhabitants of East Prussia were expelled to Germany, and in their place came colonists from Russia. The majority of the ancient East Prussian place names were changed to banal Russian names; “German” architectural monuments were destroyed.

However, the culture and language of the Old Prussians is still preserved today. The “Tolkemita” society is active in Germany; its members are former inhabitants of East Prussia and their descendants. Many of them regard themselves as Prussians. The society regularly produces collections of writing and organises scientific conferences dedicated to the history, cultures and languages of East Prussia. In the 1980s, working with preserved examples of the Old Prussian language, the German linguist Günther Kraft Skalwynas and the Lithuanian linguist Letas Palmaitis were able to reconstruct the Old Prussian language, which they named New Prussian.

Header image – the Old Prussian sacred place, Romāva (Image: Creative Commons)

© Deep Baltic 2016. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.