by Adam Garrie (Estonian World)

In terms of both historical accuracy and political strategy, more and more Estonians are turning to the concept of a Nordic political identity. Shaking the toxic “Eastern European” label could only be politically beneficial to Estonia.

National identity has always been and always will be a controversial subject, but what about regional identity? Few people have the sentimental or romantic feelings about regional identity that they do about national identity. The only exceptions to this are when large regions are summarily colonised by states from faraway places. In these instances, a regional identity is used as a means of asserting collective independence over a former imperial overlord. Sub-Saharan Africa in the 20th century is a prime example of this. But the last 300 years of European history have been about forming national identities and increasingly associating those identities with the state. This is especially true of nation states born from the remains of the German, Austrian, Russian and Ottoman empires.

The European Union is a political unit which has the potential to represent a kind of regional identity, but in spite of the EU identity entering the legal framework of many governments, it hasn’t entered the cultural vocabulary. I have never heard anyone describe themselves as European. Even local identities are more likely to come up in conversation.

Because of this, regional identities within Europe are more to do with political strategy and salesmanship rather than anything emotional, let alone violent. There are no “regionalist” neo-fascist groups as there are nationalist neo-fascist groups and one must be thankful for this. Understanding the importance of using language (in this case English, the world’s most international language) to change misconceptions of a nation becomes more clear when one listens to debates within Britain about EU membership.

Of course there are many intelligent eurosceptic views throughout Europe and, of course, this includes Britain, but here it is important to focus on the more demagogic strand of eurosceptic. Politicians like Nigel Farage, the leader of the UK Independence Party, like to talk about the European freedom of movement as the “immigration problem”. Already we see how Farage is using language to his advantage. Freedom of movement is, by definition, not immigration; it is migration, yes, but so, too, is a German moving freely from Berlin to Munich. When pressed to clarify what politicians perceive to be an “immigration problem”, figures like Farage or Theresa May (the UK home secretary who is less internationally famous and rhetorically brilliant than Farage but vastly more powerful) talk about “Eastern European immigration”. They never define what “Eastern European” means, but there is an unspoken sentiment amongst certain people that gives it a very clean meaning.

“Eastern European” does not, for example, mean Greece, although it’s one of the easternmost countries in the EU. It doesn’t mean Finland either, even though Finland has one of the EU’s largest “Eastern” frontiers. What it means are the A8 states, the states which entered the EU in 2004. These states include the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Malta. With the exception of the British Commonwealth member Malta, these states were all members of the Warsaw Pact (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were occupied by the Soviet Union at the time). In spite of some politicians in Britain and other non-Warsaw Pact states claiming solidarity with these states in the decades after the Second World War, since the 1990s these states are increasingly looked upon as socially, culturally and economically backward by certain groups. This generalisation is then extrapolated to the individuals born in these states. The tabloid papers are full of negative generations about the people they refer to as “Eastern Europeans”. While the geographical position of Eastern is not derogatory by itself nor is referring to someone coming from one of the world’s seven continents derogatory, the power of language has turned two seemingly innocuous words into a powerful statement of prejudice.

How does this affect Estonia? Well, first of all, as the country with the second smallest population of all the A8 states, Estonian migrants could hardly “flood” or “swamp” any nation. So how then to re-brand Estonia? There’s the idea of a Baltic states’ identity, but this comes with its own negative connotations and historical inaccuracies. The Estonian culture and language is not related to that of the other Baltic states. Furthermore, the term, “Baltic states”, only entered the wider English political vocabulary when all three states were occupied by the Soviet Union at the same time; hence there are more negative than positive associations with the term Baltic states. Then there’s the geographical problem that Russia, Poland and Germany have large Baltic coasts and these states have never been termed “Baltic states”.

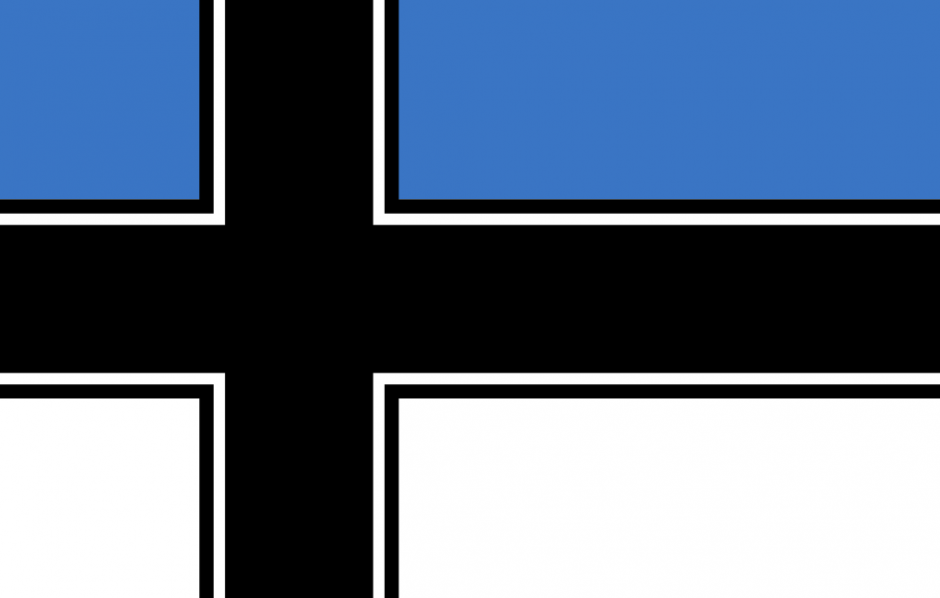

In terms of both historical accuracy and political strategy, more and more Estonians are turning to the concept of a Nordic political identity. The Nordic countries have traditionally comprised of the Scandinavian language states along with Finland. Because Estonians are ethnically a Fennic people and speak a Fennic language, many are drawing closer to the idea of presenting a regional Nordic identity to the wider world.

In terms of intellectual realities, these wider questions of a regional identity are quite silly. What’s the point of creating labels for this or that group of people when in the age of Wikipedia, anyone with a smartphone can read the basics of Estonian history in 15 minutes. But shaking the toxic “Eastern European” label could only be politically beneficial to Estonia and because no other Nordic states were in the Warsaw Pact, the Nordic brand name sells better than most others.

Exploring this topic reminds one that categories used to divide people do little to push the world further from an age of suspicion and closer to an age of cooperation. But since such labels exist for the sake of convenience, better to have a label that attracts positive attention than one which has unfortunate negative connotations.

Adam Garrie teaches modern history at King’s College London and is currently engaged in PhD level research in 20th century political history. He is a classically trained musician and enjoys writing about all styles of music, world politics and just about anything to do with Estonia.

Header image – proposed Nordic cross flag for Estonia [Image: Andres Simonson/Estonian World]

This article originally appeared on Estonian World

Check back in a couple of days for an alternate view on the subject

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.