by Geoff Chester, LIEPĀJA

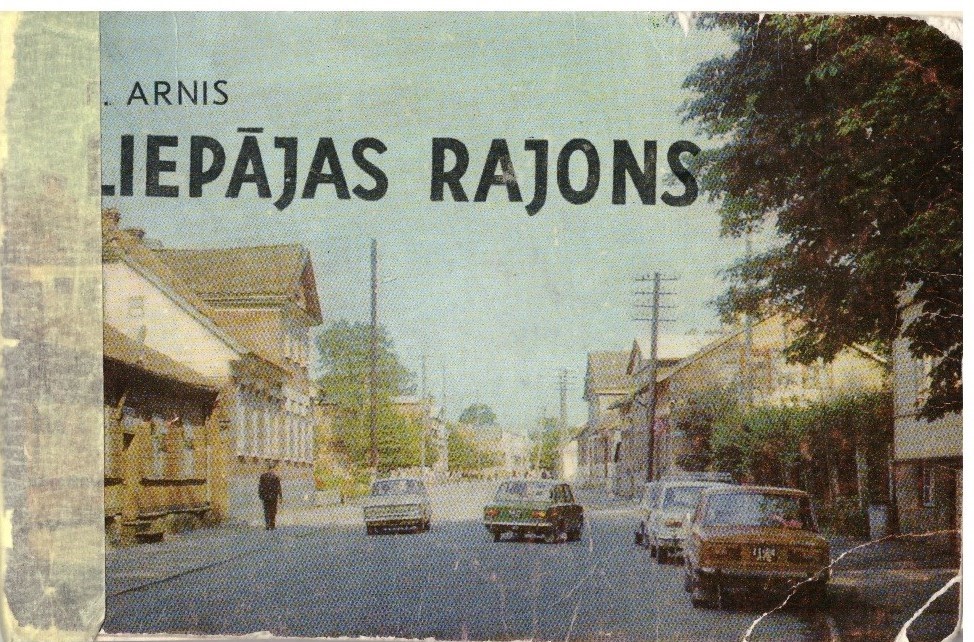

While scanning an antique bookshop in Riga one day I found a curious booklet, a tourism guide to ‘Liepājas rajons’ (sadly, for our international readers, available only in Latvian), an administrative division of Latvia which existed from 1962-2009 and is now divided among several smaller municipalities. What really caught my attention about it was how ‘untouristy’ the front cover was: a few old (though presumably when the book was published, brand spanking new) cars on a street of wooden houses. The location of this touristic site was indecipherable, and the street was decidedly run-of-the-mill.

This was a hint, the first of many, that this was a special tourism guide: one nominally designed for tourists, but seemingly only sharing information and lessons regarding the role of the Communist Party and their antecedents in the inglorious past, wonderful present and limitless future of this corner of the USSR.

One day, I took an exploratory drive with a local friend based on a route this guide recommended: GROBIŅA – PRIEKULE (35 km) – BUNKA (12km) – DURBE (12km)

This route isn’t altogether unfamiliar to me: Grobiņa is where my family’s summer house is, a sleepy town with grand Viking roots; Priekule is the nearest town to my old ancestral farm, a settlement often mentioned in family stories of war and separation; meanwhile, Durbe, Latvia’s smallest town, is one of many stops on the drive to Riga from Liepāja and a place I have visited several times for music festivals and saunas. Only “BUNKA” remained a mystery to me, although the name approximately resembles a mixture of bank and jar (banka and burka in the Latvian language) or quite simply an urban way of spelling Bunker, which is not, perhaps, the best association to have with a place.

Thankfully, I had a wonderful guidebook to hand to fill in the gaps, and a friend to show me the places the guidebook missed. The road from Grobiņa to Priekule is relatively sight-free, but despite this, my new favourite book still had some intriguing wartime stories to share that had taken place on this stretch of road:

On the 23rd June 1941, those conducting the defence of Liepāja received word that towards Priekule those opposed to Soviet power had become very active. In order to quell the disturbance, two cars left the defence of Liepāja and split up at Kaņķu hill. Those who continued straight on never returned. Driving to their destination they didn’t have any idea that Priekule had already been taken by a division of the fascist invader’s army and they were already heading towards Grobiņa.

That very same day, the Hitlerites in Priekule stopped a passenger train going from Liepāja to Rīga. A heavy assault unit took seats in the carriages. The fascists informed the driver that the route ahead was closed, therefore the train was sent back. They were only 14km from Liepāja when the head of Gavieze Station noticed the trick of the enemy and told the defenders of the city. They soon sent a train in the opposite direction. Travelling at full speed it crashed into the Hitlerite armed train.

Due to the tourist guide recommending a direct drive to Priekule, they missed out a detour through Virga and Paplaka. Curiously they didn’t mention the claim to fame of Virga, a small village where the Swedish army, led by King Carl XII, wintered during the Great Northern War in 1701. The monument to a boot he lost while fighting in the Crossing of the River Daugava in Riga proudly stands in the heart of the village.

The drive to Priekule is calm and tranquil. The pancake-flat landscape of the Baltic coast slowly transforms into the rolling Kurzeme countryside and the Rietumkursas augstienes (West Curonian uplands). The road is flanked on either side by green fields, intermittently interrupted by birch forest. The area is very sparsely inhabited, a continuing consequence of being part of one of the most hotly contested battlelines in World War II – the Courland Pocket. By the end of 1944, the west of Latvia was the only part of the Baltic countries under direct Nazi rule, the last refuge of Army Group North, the German forces originally tasked with occupying Leningrad. Over a series of five battles, the areas on the frontline between German and Soviet forces were completely destroyed. Priekule, caught between a hammer and an anvil, came out of the war completely destroyed. Of 450 homes in the town, only 40 survived the carnage.

Because of the colossal losses that took place in Priekule, the pre-war core of the city now consists of four buildings. One building, the church, stood ruined in the centre until the 1990s, while the old manor complex, consisting of the other three buildings (the Swedish gates; the manor’s watch tower; and the manor building, now converted into the local school) are the most significant remaining remnants of historic Priekule. The rest of the town is filled with typical Soviet block houses, as well as one strikingly modern sports hall built with EU funds. In the tour guide the following is mentioned:

The half-ruined Priekule Church tower stands in the eastern half of the city. In 1670, Priekule local, blacksmith Zviedris Johansons made the first trial flight in Latvian history from this very tower with self-made wings. At that time the black coats [derogatory term for the clergy] declared this to be unforgiveable sacrilege. Zviedris Johansons was presented to the locals as the very incarnation of Satan and was burnt at the stake in Grobiņa. However, the memories of the people have long held the story of the hero who wanted even at that time to begin to fulfill the eternal dreams of humanity.

Nowadays, the innovative blacksmith of Priekule is immortalised in the coat of arms of the Priekule district. The half-ruined church tower was reconstructed in 1998 along with the rest of the church. A cafe called Ikars in the sports centre pays tribute to him as a Latvianised Icarus.

While wandering down Aizputes iela from the Lutheran church to the old manor gatehouse, it’s only natural that you’ll want to know more about the revolutionary activity which took place in Priekule prior to World War II. Thankfully, my guidebook delivers:

In January 1906 revolutionaries from Priekule, Asīte, Gramzda, Purmsāti, Kalēti, Virga, Gavieze, Bunka and Rucava were sent to Priekule manor. They were locked up in the cellars of the manor, interrogated, tortured and many were shot on the edge of the park in front of the manor. “The Memorial Book of those who died in Revolutionary Struggles” mentions the names of 25 who died in Priekule. Beyond the stream on the edge of the park, a memorial plaque has been placed in their names.

The revolution was crushed. However the struggle continued. And Priekule was one of those places that saw much bloodshed.

At the end of 1918, when the town was still controlled by German occupiers, Priekule was the first place in the environs of Liepāja where a mass gathering of communists took place.

On the 27th April 1932 a spontaneous conflict broke out at Priekule market between the employees and the guards. Priekule’s workers, supported by groups of the unemployed from Liepāja, drove away and partially disarmed the guards and the police. Only at nightfall, when guards from neighbouring districts and police from Liepāja arrived, did the arrests begin. 36 active rebels were locked up.

On the 22nd December 1934, an event took place at Priekule School. The boys of the illegal Komsomol (Communist Youth League) organisation, led by Eduards Ģibietis, distributed communist slogans. Members of the underground were locked up and punished by the court.

Also during the years of the Great Patriotic War (World War II) a group of underground antifascists were active.

Beyond the Swedish gates, you’ll find Uzvaras iela (Victory Street) which leads to the most significant historical site in Priekule.

The town hosts the largest Soviet military cemetery in the Baltic countries, the Priekule Brother’s Cemetery. Over 23,000 Red Army Soldiers are buried here, a very concrete reminder of the huge bloodshed which took place 62 years ago over this small town. The memorial has recently been renovated with help from the Russian Federation. Based on the photograph from the guidebook, the ‘Memorial Ensemble’ has been upgraded a great deal since its original construction. The original statue at its heart still remains the same, a rather severe-looking mother holding a sombre-looking baby above her head. To her right, plaques are engraved in Cyrillic with the names of thousands of young men, those who died fighting in the autumn of 1944 and winter of 1945.

Having paid our respects, we head back through Priekule towards the mystery town on the list: Bunka. On the way, I absorb fascinating facts about the local farm system:

In 1977 the Sovhoz [Soviet Farm] was again the first in the region to build a new type of grain storage system according to the Latvian Agricultural Academy’s Associate Professor E Berziņš’ project…

Regarding Soviet agriculture, Priekule has one of the largest cow herds in the region. In 1976 the average yield from cattle reached 3,710kg…

Tractor factories (for example, Gomel) send various agricultural equipment to the Priekule Sovhoz for practical tests before mass-production can begin…

Upon reaching Bunka, it becomes clear that the village met a similar fate to Priekule during World War II. Flipping through the guide, we realise that the main reason Bunka made the cut was its Kolkhoz centre:

On the left-hand side of the road there is the Kolkhoz [collective farm] club. It was the first new modern building for cultural work and needs. At first there were also meetings for the best workers of the region, cultural workers and others. Now that the Kolkhoz has become one of the largest in the region, the club only has enough space for the collective alone.

Nowadays the cultural centre no longer seems to serve a collective farm. When we enter, a group of young women are working on handicrafts in the main hall. One of them comes to us and explains: ‘The library isn’t open today, it’ll be open tomorrow from 10 a.m.’ Sadly, tomorrow seems to be the only working day of the week.

At the historic heart of the village, a corner of Bunka Church stands sentinel, crowned by a storks’ nest. Next door, something found in almost every country town: a Top! supermarket. The church ruins also get a mention in the guide:

A little further along are the ruins of what used to be a church. In May 1945 the German fascist army division laid their arms down here on capitulation day. It is hoped to make a unique Victory day memorial here.

I found a little memorial nearby with more or less the same information as the guide book provided. It seems the plan came to fruition.

While wandering down Dzirnavu iela to the old mill, I come across an unfamiliar group of enemies for the first time in my guidebook. Banditi:

When all the divisions of the fascist army had disarmed and the front no longer existed, combat still continued. Bandits tried to intimidate the local inhabitants, hindering the strengthening of Soviet power. A memorial plaque refers to this time, when the then regional party work organiser Elza Tauriņa and the LCP (Latvian Communist Party) Liepāja district committee instructor Rudolfs Zemnieks died at the hands of the bandits.

The plaque seemed to have gone missing. Very confusingly, the guide never gives any addresses for the sights mentioned. Nowadays the bandits referred to by this guidebook would be referred to as ‘Forest Brothers’, partisans who waged a guerilla war against the Soviet Union in the immediate aftermath of World War Two.

In our plaque-hunting endeavours, we managed to find the old mill, the economic engine of Bunka since its founding which manages to combine old world charm with Soviet functionality.

On the road from Bunka to Durbe, the final stretch of the trip takes you through another sleepy village called Tadaiķi. Sadly, the guidebook does not provide much information about this settlement other than:

A few kilometres later,on the right hand side of the road, there is an alley which leads to Tadaiķi school. At the end of the last century, a writer and member of the new current, Jukums Paļevičs gained his first education there, and at the beginning of the XX century the doctor of medical science Professor Kristaps Rudzītis, who organised the Riga Medical Institute laboratory for tissue, physiology and pathology problems also studied there.

For those interested in the recent past, Tadaiķi now has much more to offer than just old school buildings. A former farmer from the Suvorovs collective farm opened a museum to collective farming nearby, where, in a twist of fate, the former glories of the Soviet agricultural system outlined in my guidebook are on display to this day.

As we reached Durbe, my road trip came to an end, as did my continuous exposure to this masterpiece of travel writing. I found the booklet and its contents fascinating and alarming in equal measure. On the one hand it presented a lost world, one where making money or promoting businesses was clearly not the aim of tourism boards, where the most important information you needed for your journey was about the productivity of the countryside and the numbers of revolutionaries locked up in long-past riots, where the world was in black and white. At the same time, I found the all-pervasive bias throughout the book really distracting. As a tourist, I like to draw my own conclusions based on what I can see, feel and encounter. The book seemed a little claustrophobic, with its one-track presentation of the way things were, and maybe just a little too eager to tell me how amazing everything was in this part of the world at that time. The inhabitants of towns and villages like Virga, Priekule and Bunka have different priorities and worries these days. The world back then was not any simpler than it is today.

Geoff Chester is a history buff and a proud resident of Liepāja. He is also founder of Novus Novuss, and owner of the first Open Office/Novuss game hall in Liepāja, Graudu iela 34

Images – Geoff Chester, unless otherwise indicated

© Deep Baltic 2017. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.