Deep Baltic presents an exclusive extract from Latvia-based writer Mike Collier‘s latest book, Up the Baltick. Presented as a remarkable literary find, the novel dramatises an expedition through this part of the world by the celebrated 18th-century writer and thinker Samuel Johnson, the author of the first dictionary of the English language, and his amanuensis and biographer, the Scottish writer James Boswell. During the journey, recorded by Boswell, the two travel through modern-day Latvia and Estonia, then part of the Russian Empire, stopping off not only in Riga and Tallinn, but also in Liepāja, Jelgava, Tartu and Mustvee (or Libau, Mitau, Dorpat and Tschorna, as they would have known them), amongst other locations. As Collier explains in the following passage from the book’s introduction, there is evidence from letters that Johnson and Boswell were genuinely considering a trip “up the Baltick”, following the successful journey they made through the Scottish islands in the autumn of 1773, written up in the travel narrative A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland.

The two men had even discussed the possibility of a second journey while still engaged on the first, a fact recorded by Boswell himself:

“It appears that Johnson, now in his sixty-eighth year, was seriously inclined to realize the project of our going up the Baltick, which I had started when we were in the Isle of Sky.”

In a letter to Johnson dated September 9, 1777 he writes:

“Let us by all means have another expedition. I shrink a little from our scheme of going up the Baltick.”

The title of the present work is taken from these instances.

In The Life Of Samuel Johnson, written years later, Boswell quotes a letter of September 13, 1777 from Johnson to Mrs Thrale which says:

“Boswell… shrinks from the Baltick expedition, which, I think, is the best scheme in our power… it is a pity he has not a better bottom.”

Boswell then goes to great lengths to explain in a footnote the reasons why this expedition never took place, saying:

“I am sorry now that I did not insist upon our executing that scheme. Besides the other objects of curiosity and observation, to have seen my illustrious friend received, as he probably would have been, by a prince so eminently distinguished for his variety of talents and acquisitions as the late King of Sweden; and by the Empress of Russia, whose extraordinary abilities, information and magnanimity, astonish the world, would have afforded a noble subject for contemplation and record. This reflection may possibly be thought too visionary by the more sedate and cold-blooded part of my readers; yet I own, I frequently indulge it with an earnest, unavailing regret.”

Here, Boswell is remarkably apologetic. It is not entirely implausible that the trip “up the Baltick” had in fact happened and that one or both men wanted to keep it quiet.

Here, we present an extract from a chapter entitled “Marienburg – City of Enlightenment”, where Boswell and Johnson visit the small town of Marienburg (now Alūksne in northern Latvia), and come across a Baltic German baron with wild plans for its improvement.

Marienburg is a vast city equal in size with London, planned with perfect regularity both architecturally and in its social organization. Here all is tranquillity and contentment. All have their place and are satisfied with it. Learning is held in high regard and literacy is universal. Poverty is reserved solely for those unwilling to participate in the general progress and only the indolent are allowed to starve. Even the insane are shown consideration, being provided with a model institution presided over by a dynasty of physicians no less conscientious than the Monros of the Bethlem Hospital,[1] who I take pride in reminding the reader who has accompanied me upon my journey thus far, are another example of an eminent Scottish clan, in his case the Monros of Fyrish, dedicating themselves to the betterment of humanity.

Such at least is the vision of Marienburg’s owner, Baron Otto Hermann von Vietinghoff-Scheel, who shall hereafter be referred to by the name of Baron Vietinghoff (with two ‘ff’s). We had made the acquaintance of this fascinating individual in Riga, during the episode of the theatrical visit previously related. We were lucky enough to take up this nobleman’s invitation to join him at home in Marienburg, where he was preparing his summer residence and the many great projects which he has planned for this unlikely corner of Livonia. His time is usually divided between Riga and Petersburg, where he has palaces and holds several important offices.

At present Marienburg is unimpressive enough despite a certain rudimentary attractiveness provided by nature. There is a large lake with some small islands and some little hills which afford a pleasant view without too much effort in the ascent. The town itself barely merits description as such, being really a large village indistinguishable in character from most others in Livonia.

But all of that is certain to change, at least if the Baron Vietinghoff has any say in the matter. It is unfortunate that places do not attach themselves to the names of the Livonian nobility in the same manner as in Scotland. If ever a nobleman had earned the right to have his name identified with the name of a place dear to him, it is this Vietinghoff who would certainly not disgrace the title of Graf Marienburg.

The Vietinghoffs first came to Livonia with the crusaders and were masters of a castle that now stands ruined upon one of the islands in the lake. They ruled wisely for many centuries but, as occurs at some times in even the greatest families, luck temporarily deserted them for a few generations when they found themselves at odds with the pleasure of the sovereign.

They were forced into exile from Marienburg but never forgot it and by a process of careful re-accumulation of prestige and wealth, in the middle of this century the Baron was able once again to buy back his ancestral seat, restore his rule over his traditional lands and again set to work improving them for the benefit of all.

The last years he has spent as patron to a talented young architect named Haberland,[2] whom he has commissioned to draw up plans for a handsome city that will one day stand upon this spot, a city worthy of modern and scientific Europe with broad streets, elegant churches and parks provided for the entertainment of the populace from the highest to the lowest, each class to have a park assigned to them so that they might recreate without fear of censure or embarrassment.

The park for the nobility and gentry is already being laid out and, after receiving a letter which General Browne had asked us to convey to his friend,[3] Baron Vietinghoff immediately proposed a tour of the park.

“Messieurs, I could not have asked for more welcome visitors than an Englishman and a Scotsman (I was flattered and impressed that he immediately recognized the important difference between the two). I have always wanted a park such as your famous ‘Capability’ Brown might be able to provide. I recently had the good fortune to visit England and saw some of that ingenious man’s work in the flesh, so to speak. I have tried to bring a piece of Brown’s England back with me to Marienburg here, in the park I have laid out in accordance with Brown’s principles. I would be eternally in your debt if you would give me a true and honest opinion of its defects and any merits it might possess.”

Dr Johnson bowed graciously and said that, though no gardener himself, he had seen Brown’s work at several houses in the country and would do his best to provide the requested comparison.

“Sir, I met Brown a couple of times,” said Johnson. “The first was at the house of General Clive, recently returned from his duties in India. Clive proudly showed him the house, drawing his attention all the time to his trophies and coming close to boastfulness. As you know, Brown is like myself of humble origins and therefore less susceptible to being impressed than another nobleman might have been. Pointing at a great moghul chest in his bedroom, Clive said: ‘When I was in India, that chest was full of golden coins.’ Brown replied: ‘Sir, it is remarkable you can bear to have it so near your bed.’”

Johnson continued: “The next time I saw Brown he told me how he enjoyed my Dictionary and said our work was very similar. I asked him how so and he replied: ‘Now there (pointing his finger at the distance), I make a comma and there (pointing to another spot) where more of a turn would be proper, I make a colon: at another spot – where an interruption is desirable to break the view – a parenthesis. Now a full stop. And then I begin another definition.’”[4]

Now turning to me the Baron Vietinghoff said: “I have no less regard for the clans and castles of Scotland, which offer a romance that is so attractive to us in these wild, windswept lands here. You should be doing me a great honour, Laird Boswell, if you would survey the ruins of my castle and give me your advice on how it might be presented as a scene in the sublime mood.”

I told him that as my father was still alive I should not be called ‘Laird’, though I appreciated his effort to ennoble me so early. Dr Johnson found this amusing, I suppose because he noted a certain pride in my demeanour, which I do not deny.

After establishing us in fine rooms in the best house in the town, next to his own, Baron Vietinghoff gave us some hours to refresh ourselves before admitting us to dinner.

Over the finest meal we had enjoyed since Riga, taken in a room clothed in wooden panelling that would have done credit to any St James’ club, he outlined his intentions for Marienburg. How Augustan it must be to establish not only a house according to one’s own plan but an entire town and region!

The Baron’s plan is well-thought-out and seems eminently achievable. In addition to the his sentimental and familial attachment to Marienburg, he has realised that it stands at a remarkably fortuitous location. The routes from Riga to Pskov and to Petersburg pass close by, and Marienburg is a little over around halfway from Riga to Dorpat. The forests nearby are well stocked with mature trees and the sandy soil makes the levelling or raising of ground and the construction of roads simple. With a little maintenance and provision of services for travellers and merchants, there is no reason Marienburg should not become an important town – or city – for the conducting of trade and exchange.

In addition, the natural surroundings are exceedingly beautiful, the water clean and healthy and the forests devoid of dangerous creatures. During his years summering in Marienburg, the Baron has noted a substantial improvement in the health of himself and his family and consequently has hopes that Marienburg might also be suitable for development as that most fashionable of things, a spa. In short, a Bath combined with a Bristol, here in the heart of wild Livonia! This might well sound outrageous to the reader but when one has seen the natural advantages of the place and the wise determination in Baron Vietinghoff’s blue eyes, it no longer seems fantastical. After all, what was Bath one hundred years ago but a village for drovers and sheep-shearers? Now it is the most fashionable residence in England.

Naturally, the construction of a city requires large amounts of stone. In order to obtain this, the Baron has already instituted a school for stone-cutters where many peasants are being instructed in this art and will be able to support their families with the new skills taught them for many years to come as the city grows about them.

The Baron has also a distillery producing votkey and other spirits, a tannery, a manufactory of linen from flax that is said to be the best in Livonia and a pottery that produces very good roof-tiles. This last is particularly important for what good are the walls of a fine building with no roof to protect them from the Baltick snows?

“Our city will not be one of paper and plaster, Messieurs, but one of real stone built to stand the climate,” the Baron said in what I took to be a reference to a certain other grand city built in an inauspicious location that I shall leave it to the reader to deduce. This reasoning tallied strikingly with my own musing, as previously noted.

He has also set up a mill for the sawing and preservation of timber and sundry other industries that should contribute to this town’s economic prosperity even if the grand plan of construction is delayed, as is sometimes the case with truly ambitious undertakings. Such initiative is surely to be highly praised, doing far more for the poor than charity, which has a tendency to destroy self-reliance while encouraging indolence.

After dinner we were taken to meet the family of this amiable man, whose personal life is so in keeping with his principles of warm humanity. The Baroness Anna Ulrika is an exceedingly elegant woman, yet vivacious and natural. She is the grand-daughter of the famous General von Münnich who led our own General Browne when he was a young man fighting the Turks, and who was also a rival of the Biron about whom we heard so much at Mitau.[5]

Indeed it is instructive to compare Marienburg and Mitau in the mirror provided by these families of equivalent rank; one characterised by true yet humble nobility; the other by excess in all things, from the opulent luxury to the deprivations of Siberian exile. The Vietinghoffs returned to their native city by application and decades of hard work; the Birons by a caprice of the ruler very like the one that sent them into banishment. Kurland is crammed full of palaces built quickly with no other purpose than to look splendid, and which are already rotting where they stand; Marienburg has no palace, but careful plans for an entire city that makes sense and will last many years. Meanwhile the Baron lives in a sensible town house.

[1] The Scottish Monro family held sway over the Bethlem Hospital in London – the world’s first dedicated mental institution – for 125 years from 1728. At the time of the Baltic journey, the chief physician of the hospital which gave the world the origin of the word ‘Bedlam’ was John Monro. He held the position from 1752 to 1783.

[2] Christoph Haberland (1750-1803) was an architect who was born and died in Riga. He was a pioneer of classicism in the region.

[3] As well as being friends, Vietinghoff was in effect second-in-command to Browne in Livonia. Their dynasties were eventually united when Browne’s son married Vietinghoff’s daughter.

[4] This anecdote is similar to one told by the writer Hannah More about a meeting with the famous landscape gardener Capability Brown in 1780 at Hampton Court. More and Johnson were acquainted with each other.

[5] Once allies, Count Burkhard Christoph von Münnich (1683-1767) and Ernst Biron became adversaries. Ironically, both were sentenced to death, had their sentences commuted to exile in Siberia and were eventually allowed to return home after more than 20 years. Münnich was responsible for considerable modernisation of the Russian army, including the founding of the famous Izmailovsky guards regiment. Baron Münchhausen was a fellow officer at the siege of Ozi, which is immortalised in one of his tall tales. Münnich is buried at Dorpat (Tartu).

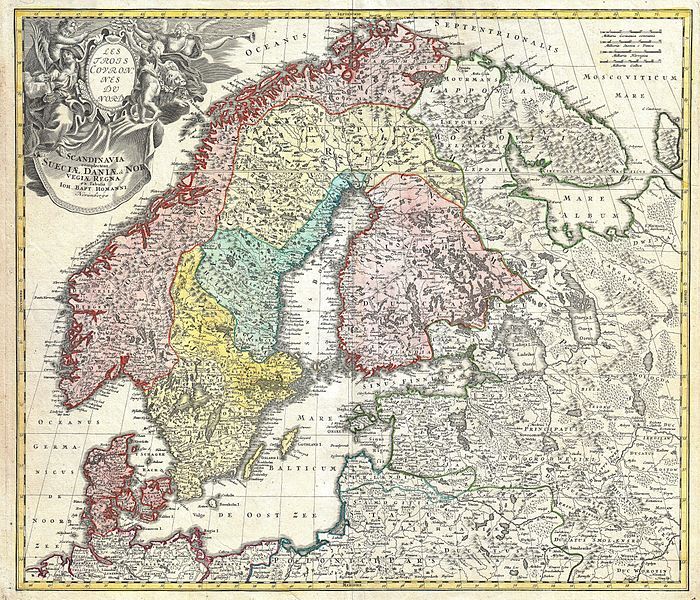

Header image – J.B. Homann’s c. 1730 map of Scandinavia [Public Domain]. All other images credit Mike Collier unless otherwise specified.

You can purchase Up the Baltick here. For more information about Mike Collier’s work see this Deep Baltic interview with him from last year, as well as this extract from his previous collection of short stories, Baltic Byline.

© Deep Baltic 2017. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.