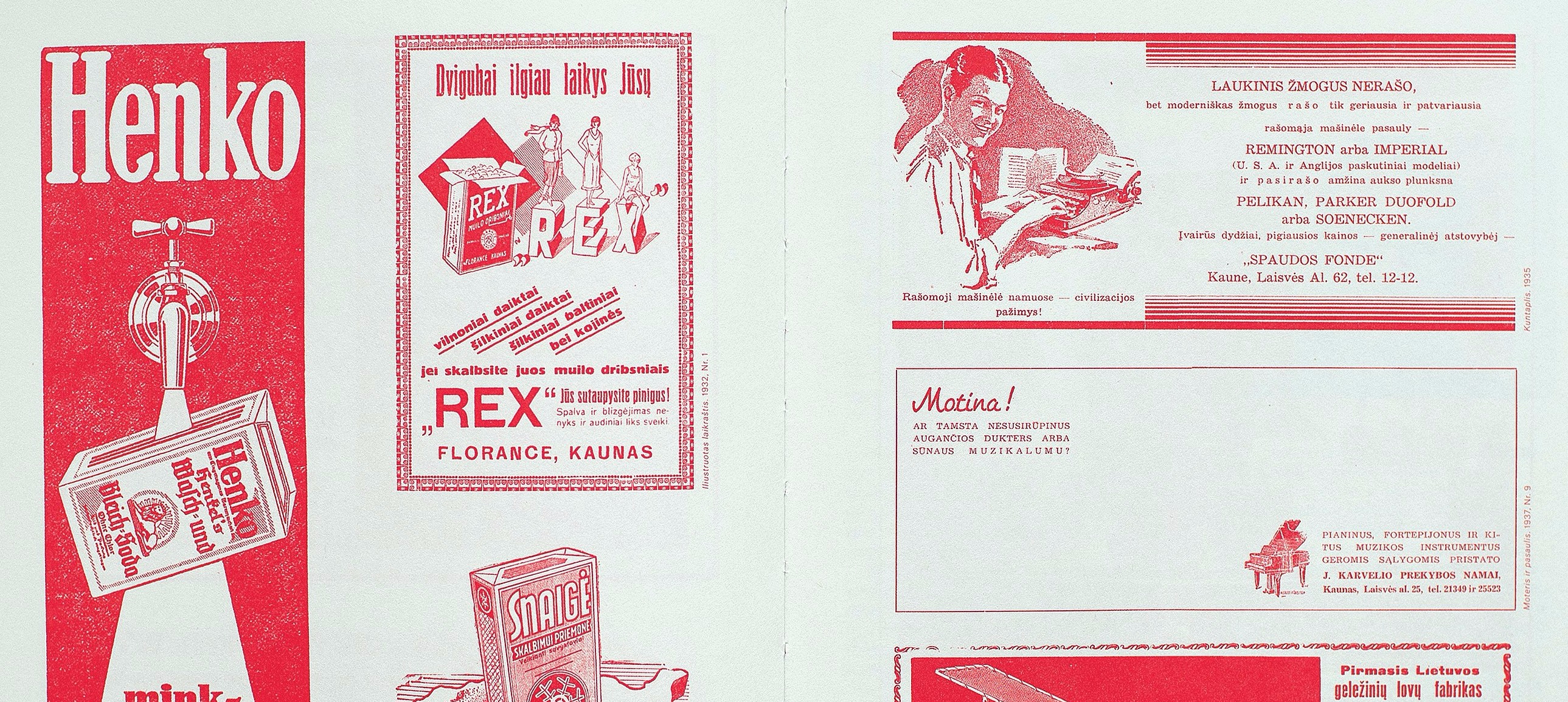

The book Interwar Lithuanian Advertising [Tarpukario Lietuvos Reklama], compiled and published by Ramūnas Minkevičius and designed by Laura Klimaitė and Miglė Rudaitytė, collects many of the most striking, colourful or simply strange examples of adverts produced in the Republic of Lithuania in the interwar period. The country had declared independence from the Russian Empire in 1918, and these years were a time when the concept of advertising was being born in Lithuania. The book was enthusiastically received in Lithuania when issued in 2015; it was also the winner of the Book Art Contest of the Lithuanian Ministry Culture and was awarded the title of Most Beautiful Lithuanian Book at the Baltic Book Art Festival in Tallinn in 2016.

An introductory essay by Lithuanian advertising expert Tomas Ramanauskas puts the images in broader context.

I am not a historian and therefore do not know where the advertisements of the interwar period stood in terms of the general cultural and social context of the time. However, looking over the ads today, it’s clear that the modesty and relative sophistication which characterise communication today were nowhere near as important – with the exception of butchers in the former case, and electric equipment salesmen in the latter. Advertisements of the period promised the entire world – and even that was not always enough. Its subjects were simply unrivalled, and capable of changing lives and destinies – in other words, they were downright shameless. Or, more appropriately, playfully shameless.

It’s no wonder that advertising from the American ideology-obsessed interwar period made no attempt to hide its admiration for everything originating from across the Atlantic. “In terms of advertising perfection, America has beaten all the records imaginable,” wrote the press, taking every opportunity to dish out praise. To be fair though, the Swedes also received their share of applause: “in Sweden, distinguishing between advertising and necessity is quite a difficult task”. Phrases were being written at the time that still resonate with our very Lithuanian insecurities – we are not capable of doing this.

Overall, the advertising industry did not lack self-awareness, and this was reflected in the press – perhaps even more so than today. There was also more criticism. Let’s look at the advertisements displayed in film theatres. Posters and newspaper ads tended to announce every film, regardless of quality, as a “true masterpiece”, “an unparalleled artistic triumph”, “a miracle of light”, etc.”, which was an astute observation about the industry at the time. The world of advertising was on a rampage.

Tobacco products, not yet as lambasted for the problems of humanity, resultant health issues, the yellowing of teeth and sallow skin, crooned like an angel playing on a harp: “a cigarette guides the smoker to smoky paradise”, “Pasagos cigarettes bring happiness”, “those who want to reap the pleasures of smoking must begin today”. Even though alcohol ads were not as bold, with the NTAKD (Narkotikų, tabako ir alkoholio kontrolės departamentas – Narcotics, Tobacco and Alcohol Control Department) not yet having been established, there was no one to notice the occasional slip-up: “An advertisement of the Pergalė liquor depicts children reaching for a bottle, accompanied by a clear conclusion: “that’s what everyone is demanding!”.

The desire of Antanas Smetona [Lithuania’s authoritarian leader from 1926 to 1940] to keep Lithuania in his grip was shared by the creators of ads (although it’s difficult to say if the years line up perfectly), who liked to supplement them with an injunction, sometimes even a severe one. The word “only” was often seen in advertisements: people were told to wear only one specific type of shoe, use only one kind of deodorant and buy only a certain brand of cigarettes. This is quite uncomfortable as they sound like commands. The concept of a “hard sell”, originating in the field of sales, gained a severe expression here, resembling the harshness of the army. “Buy immediately” cried out one product; “you lack”, commanded another. Sometimes even the loyalty and focus of the reader were cast into doubt, even though, at the time, newspapers held people’s attention much more reliably than basketball championships involving the Lithuanian national team do today.

An advert for the state-run lottery says “in the past, treasure was brought to farmsteads like these by a kite – now it’s done can by everyone”

Another frequent occurrence is the use of the word “everyone”: “everyone advertises”, “everyone wears”, “everyone eats”, with a trademark attached at the end. This simple tactic leaves no room for doubt – if everyone is interested in a certain product, it must be the best one. Even then, the desire of marketers to preclude the audience from thinking too much was quite evident. What worries me is that many providers still treat advertising in the same way, minus the mischievous, old-timey way of speaking – it is often blunt, abrasive and lacking inspiration. Knowing how many tools of manipulation the world of advertising has acquired over the years, this is really quite sad.

The imperious tone went on to acquire a plethora of different shades. Doubts over how dedicated the reader was often led to quips like “don’t read any further before finishing this ad”. Farmers were addressed with even less respect: “hey, farmer, what you’re doing is wrong”, proclaimed a caption for a saltpetre ad. When all other means of influence failed, texts would sometimes devolve into infantile foot-stomping: “stop!”, chastising the reader as if she were a little girl.

Today we like to talk about the respect paid to consumers by brands, about getting off one’s high horse, and about what’s real and natural, whereas advertisements of the interwar period did not take consumers to be very intelligent, instead choosing to imply what they should be thinking. “I don’t want that!” an angry character shouts at his wife, because only Maisto canned food is appropriate to snack on. Even wearers of tights spoke constatively: “I tried many different brands, but now I only go for Cotton”. “In a hurry for a tasty meal”, a restaurant channels its patrons’ desires.

When arguments were in short supply and simple commands seemed inappropriate, one of the most popular methods of the time was making impossible promises. Advertisements offered people models of behaviour and a solution to all their problems: protect your health, don’t ride low-quality bicycles, accomplish a day’s worth of labour in just two hours with a new harvester, memorise the mantras “sugar gives you energy” and “coffee protects the heart”, and never forget the source of your youth and purity (a facial cream). Some of the conclusions, presented in all seriousness, verge on the comical and absurd: “why choose soap from Kipras Petrauskas?”, an ad would ask unprompted, and immediately reply, “because it is, and always was, simply the best”. Who could possibly doubt that?

While there was never any lack of nonsense, more worrisome trends would also appear, such as sexism (it’s unlikely that anyone would have noticed that in Lithuania at the time), manifesting itself in the form of an inscription by a sleeping woman: “she often dreams of a Lietūkio sewing machine“. If that’s not offensive enough, then how about a man, holding a woman by her fringe with both hands and inspecting her against the light like a new trophy dinner plate – a new toothpaste appealing to the conscience of consumers. Next, a cheerful black person, depicted on the package of black shoe polish by Pasaka. It all happened well before Rosa Parks sat down on the wrong side of the bus, making racial awareness nearly impossible.

Lastly, at the bottom of the list in terms of quality, we find second-grade-level poems and puns. A headless man demonstrates ways of “losing one’s head”; an image of the palm of a hand is inscribed with the text, “as clear as if written on a palm”; and a shoe is lifted to reveal the sole containing the warning, “don’t step on happiness”.

The interwar period was the dawn of Lithuanian capitalism, as understood at the time, which could explain why steps taken in the field of marketing were so childish. That’s also the source of commercial titles, many of which were blunt, yet earnest: Milk Centre, Letter Publishing, Motosport, Food. It seems, however, that as the market became increasingly more saturated, advertisers gained a new degree of ingenuity. Cigarettes were sold under names like Kanklės, Gypsy, Prophet, Riddle; beauty creams acquired the title Metamorphosa; and candies were marketed under the name Radio. Consumers also were given the opportunity to enjoy a wide variety of foreign brands, such as Ford cars and Nokia galoshes.

Spending time looking at the press and advertising of the interwar period can be quite contagious. This might also be the reason why our agency recently came to help Volfas Engelman, a beer made in Kaunas, find a unique style which utilises the sentence structure of the interwar period. Only with a tad more modesty.

The shameless ads of the period now amuse us with their texts, old-fashioned linguistic conventions and hilarious choice of words. However, even with their limited means of conveying their ideas, the advertisers of old were still ahead of us in terms of visual style, visual clarity, and memorability. A closer look also reveals their superior and insightful expressions. “Knocked out! My Buddy tobacco serves a death blow to all other brands”, proclaimed one such ad. This type of fun, unsophisticated, well-meaning, yet insolent communication could “knock out” our stagnant views about what is good and bad.

Advertisers of the interwar period could really teach us some naiveté and forthrightness – they were eager to sell, and not shy to be blunt about it. Some did it with grace, while others weren’t as smooth. In any case, this is part of our history – and what a colourful history it is, despite being in black and white.

To find out more about the book, you can go to its official website (in Lithuanian). Interwar Lithuanian Advertising also has a Facebook page.

All images credit – Tarpukurio Lietuvos Reklama

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.

© Deep Baltic 2017. All rights reserved.