“[C]rude, tropically hot, menacingly rapturous”— from a review by an émigré Lithuanian critic that anathematized émigrée poet Birutė Pūkelevičiūtė’s Metūgės, her debut book of poetry published in Canada in the early 1950s.

“A Literary Gem: now accessible to the English-speaking world”—from the newspaper Draugas News regarding my 2023-25 website [newshoots.pub] that presents some poems from the first complete English translation of Metūgės [“New Shoots”].

The last 70 years saw changes, including for women poets. The Lithuanian diaspora was affected by waves of feminism. Émigré literature became more freely available in the independent homeland.

The history of this book of 33 linked poems can be summed up briefly.

First Edition, 1952

Metūgės was initially published by a small press in Toronto in a small print run. Harsh comments by some influential émigré critics harmed the book’s reception and prompted the poet to turn to prose. Pūkelevičiūtė did win prizes for her novels and became a prominent figure in émigré Lithuanian cultural life, including for her theater work, children’s books, and opera libretto translations.

From that time, I could find only one translated Metūgės poem published: first in the émigré publications Vytis (a periodical) and The Green Oak (a book of selected Lithuanian poetry) and then in the anthology of elegies on children The Cry of Rachel (also containing poems by major international poets). Much later, the same poem (beginning with a mother compared to a bird cherry tree) appeared in a markedly different translation in the anthology of literature Lithuania: In Her Own Words.

Second Edition, 1997

Some years after Lithuania regained its independence, a large press in Vilnius printed a larger run of Metūgės. This edition included a poignant, revelatory introduction by the poet herself, which I have translated below.

A Look at Metūgės—44 Years Later

Metūgės was my firstborn book, yet she had to endure a stepdaughter’s lot: For many years, she (like Cinderella) shelled peas by the hearth. And even now—though a second edition’s carriage has come jingling to her door—it’s doubtful she’ll dance in a shining castle with the princes of Lithuanian poetry. Not the time for dancing. Not the time for glass slippers.

In the diaspora, the climate for the appearance of Metūgės was painfully unfavorable. Today, in retrospect, the scathing criticisms of this book’s morals and eroticism seem worth merely a smile. Perhaps in those days the glaciers of artificial morality had slid in, making human emotions incomprehensible to the prophets. On the other hand, only now reading memoirs have I begun to realize what a closed community the young Lithuanian poets were. They had their own “codes,” and almost all of them wrote in the same spiritual tone, though choosing different forms. So to the meteors streaking in this orbit, I was an utterly alien pebble: fallen from another world. Probably also because I came from the theater, I was not a “woman of letters” among a circle of peers but a “harlequin.”

It’s possible that Metūgės was a bit anticipatory with its female stance: From afar, the drums and whistles of the approaching feminism were still inaudible. But I, though not a “feminist,” was nonetheless a “femina.”

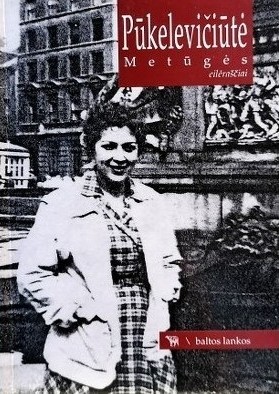

My photographs were requested for this edition—from those times. While sifting through faces and images of the past, I reflected that the axis of Metūgės revolves around the loneliness of a young woman—in a foreign country, in a foreign city, Montreal—in the aftermath of a terrible war. How dreary Sundays were in the half-dead city, when trams sounded from afar, when I watered sad flower plants grown on the windowsill! Like a huge cloud, sorrow and longing would then sweep in for what was lost—twelve strong brothers who would block the wind with their shoulders. And more: an aching craving to create God in your own image, who would sit with you on the threshold in the evenings.

So is poetry a record of ravings? A proclamation of illusions? After all, in reality I was never a she-wolf, nor a lynx, nor the green snake. Far from it: I was a very ordinary girl. Perhaps the unreality of poetry lies in the human soul—it’s the unease of small truths and a lethargic state of rebellion. It’s a caressing of dreams; it’s a yearning for what is not. Or, according to ancient wisdom, poetry is what could be. Magic.

I have always valued the image more than the concept. In Metūgės, I sought the economical word and especially the concise sentence. For example, I was very happy to comment on death briefly and simply: “My death is beautiful.” I had inscribed a motto for the book, but it crumbled away by mistake at the printer’s. It was Walt Whitman’s sentence: “[And] If the body were not the soul, what is the soul?” That is how I thought then (I think similarly now) about the unity of body and soul.

I should add that the extremely harsh reception of Metūgės prompted me to change genres quickly and make friends with prose. My second book was [the novel] Aštuoni lapai [eight leaves]. To mark its publication, Metūgės artist Juozas Akstinas created an oil rendition of his illustration for the “Coming of Spring” section (a girl’s head) and presented the painting to me. That was a touching memento of my debut book.

But she herself, the small green Metūgės book (as I mentioned)—remained by the hearth to shell peas.

Birutė Pūkelevičiūtė

1996 07 12

Subsequent to the second edition, more poems from Metūgės were translated (into English and Spanish) and published, and significant literary criticism appeared that praised the work. Another spurt of articles in the Lithuanian press was prompted by Pūkelevičiūtė’s birth centennial in 2023. But there was still no complete translation of her debut book of linked poems.

New Translation and Website

While searching for an absorbing project in 2020 at the start of Covid Time, I received a first edition of Metūgės from a friend. I found many of the images startlingly original, the free verse unusually musical, and the 33 poems interestingly linked. But most significant, and surprising, was that the poems were on bold topics by an émigrée Lithuanian woman poet writing and publishing in the early 1950s, presenting vignettes in the life of a strong, passionate woman. I started translating the work.

Only later did I learn about the harsh reception of Metūgės. That was less of a surprise. My thoughts ranged from how long the Mexican Sor Juana’s poetry remained untranslated and unknown to the plaintive 1968 lines of U.S. poet Muriel Rukeyser: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.”

Translation has allowed me to engage with these challenging poems on a deep level and to appreciate their beauty and complexity. As insightful articles have pointed out, Metūgės shows intriguing influences, for example, the sensuality of the Song of Songs. I even see humor and satirical touches reminiscent of Carmina Burana (which Pūkelevičiūtė translated). But always that originality of images, that atypical musicality, that focus on a woman’s view.

Wanting to commemorate the poet’s birth centennial in 2023, that November I launched a website for Metūgės; it includes some of my translations as well as much other material relevant to this book of poetry and to the poet.

A few of my translated poems are presented below. I hope this work will generate international interest in Metūgės as a milestone in women’s literature (it precedes by a year the first poetry books of Ingeborg Bachmann and Joyce Mansour) and in Birutė Pūkelevičiūtė (1923-2007) as a gifted, innovative, and prescient poet.

From “Coming of Spring” (Section 1)

Green windmills spun by whistling wind —

Green windmills sunk knee-deep in soft, warm grass.

The sun sphere flames on a gold-haired giant’s palms,

heated lakes overflow their shores, and uncut meadows

sough like seas — with milk, and honey.

Bright May now celebrates his wedding, and

drunken bees at evenings don’t find their hives . . .

Let’s both go to the woods.

It’s quiet here:

Black spruce branches sway to the ground. No warbling

by birds napping after noon — only in a thicket the great

heart of the forests pounding loudly.

Hear it?

Her beats are heavy and uneasy.

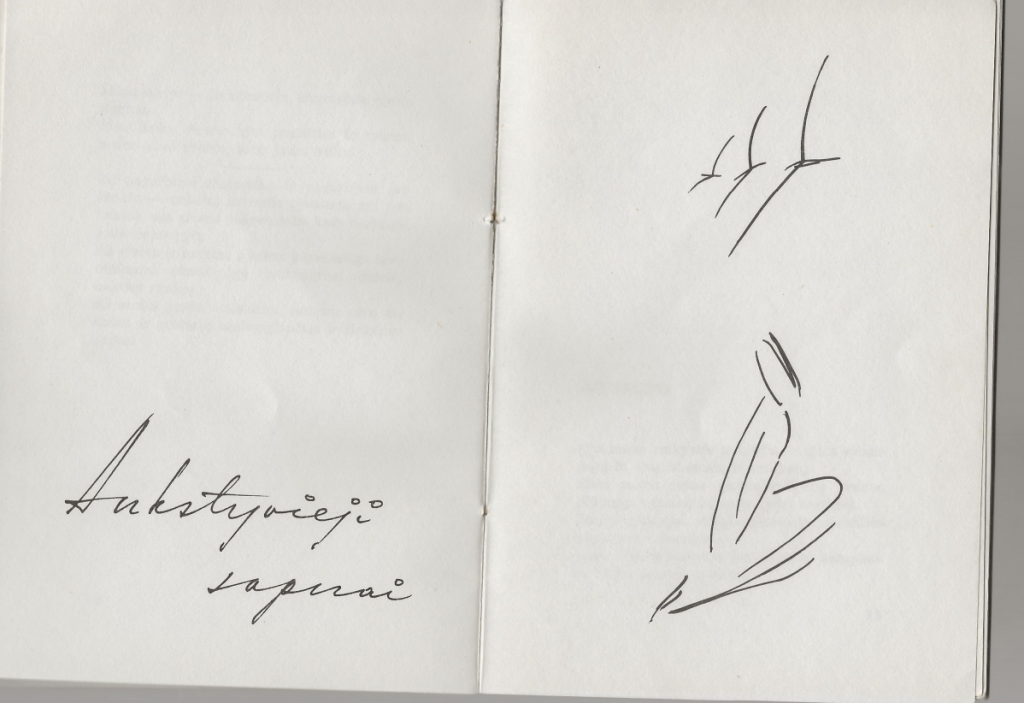

From “Early Dreams” (Section 2)

My mother, slender like the bird cherry tree.

Burdened by me, she ripens misfortune.

Wide bowls filled with pine grove flowers. Yellow

shutters half shut:

She waits for the holy day.

I arrive during the Elevation, when all roads are

empty, when the organ is muted.

At night my cradle fills with piercing August

stars and my mother begins crying bitterly.

For the first time.

Because I split off, like a chunk of cliff, and will roll

down. Without her.

And really:

She can’t hold onto my hands.

Autumn orchards burn with red glows. Wild drakes

fly south. Their wings glitter with brass.

So then I say goodbye.

The path in the rushes narrows. Sedges sharpened

like knives.

Toothless tree hollows gape and all my joints

tremble.

But I don’t turn back.

From “To Girls” (Section 4)

I want to eat.

With teeth I want to rend bleeding muscles of

robust animals, crush the hard kernels of nuts.

I bring hooped baskets of helpless fruits.

With nails I dig into their feverish cheeks and

tear them open.

Tart sweetness drips down my palms.

Give me the black pike, the painful sourness of

forest berries and pungency of junipers.

I want to suckle earth’s roots — take in all

her secrets and bitter juices.

I want to drink —

Suck all springs dry up to their source. Drink

from thin glass goblets and clay pitchers.

From pitchers — foamy milk.

Milk: the first and only wine.

Aušra Kubilius, a retired professor of English who lives in the United States, translates Lithuanian poetry and prose.

© Deep Baltic 2025. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.