by Vincent Hunt

Twenty years passed. Latvians held senior jobs in the Soviet regime in economic planning, the military, in the arts and in the security police. Their homeland was free and their cultural organisations were flourishing in the Soviet Union. But Stalin was suspicious. Latvians were “Old Bolsheviks” – they had been loyal supporters of Lenin and took orders from Trotsky while in uniform. As he embarked on a ruthless purge of his rivals and enemies from the Politburo and public life, he declared Latvians bourgeois, counter-revolutionary and nationalistic, and ordered them to be liquidated in a ‘national operation’ in which an estimated 70,000 people were killed or exiled. Other nationalities – Ukrainians, Germans, Finns, Armenians, Chinese, Koreans and especially Poles – were also targets of Stalin’s Great Terror.

The order for the ‘Latvian Operation’ was issued on November 30th, 1937:

Coded Telegram Nr. 49990 on conducting operation for repressing Latvians.

ConfidentialTo all People’s Commissariats

Chiefs of UNKVD (Ukrainian branch of NVKD secret police)

Chiefs of DTO GUB (Special authority for state security)In Moscow and other areas large Latvian spying-diversion and counterrevolutionary organisations are working undercover, created by the Latvian intelligence service and in contact with other spying agencies. These contrarevolutionary formations have joined a pro-Trotskyist and military-Trotskyist conspiracy in nationalistic Latvian centres and branches. To liquidate the work of the Latvian intelligence agency and to crush Latvian anti-Soviet actions in the USSR I give the following orders:

- On 3 December 1937 swiftly in all republics and regions conduct arrests of all Latvians suspected of spying, diversions and anti-Soviet actions.

- Arrest all Latvians who are:

a) in operative surveillance or in development

b) political emigrants from Latvia who entered USSR after 1920

c) defectors from Latvia

d) chiefs, members and workers of Prometejs (Prometheus) society and Latvian clubs

e) chiefs and members of the Latvian Rifleman society and members in OSOAVIAHIM (Society for defence, chemical and aviation production)

f) former chiefs and members of formerly working stock society ‘Produkt’ and ‘Lessoprodukt’.

g) Citizens of Latvia, excluding the workers in diplomatic staff

h) Latvian tourists in USSRSigned by Yezhov, chief of Soviet Secret police

Then known as the NKVD, the Cheka showed no mercy in the purges of 1937–38 to those Latvians who had been significant personalities not only in the Bolshevik movement but also in its own development. From 5 January until 20 July alone, there were fifteen mass executions in which 3,680 Latvians were shot. One file, the Yurasov card index, lists the names of more than 1,000 Latvian victims, shot between 1937 and 1938. They include rank and file workers, collective farmers, engineers and teachers as well as professors, journalists, writers and diplomats, officers and secret police. More than a third are veteran Bolsheviks from the 1905 revolution, former political prisoners, exiles or former underground fighters. All were accused of spying for bourgeois Latvia and shot – some with a bullet to the back of the head, others by firing squad.

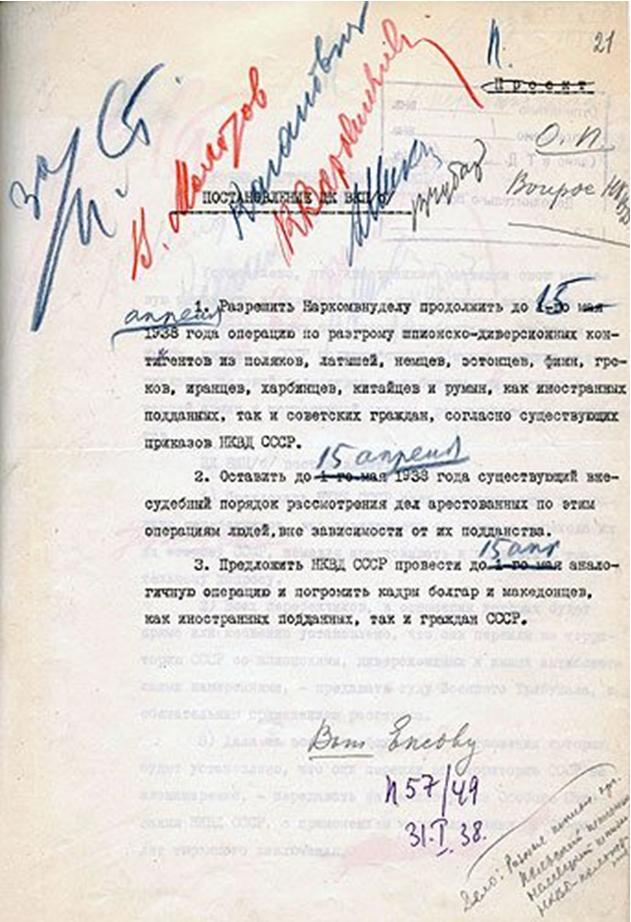

Almost all Latvians serving in the Communist Party and state and security sector were rounded up and arrested, including senior party figures like Jānis Rudzutaks, Red Army commander Jukums Vācietis, Air Force boss Jēkabs Alksnis, Corps Commander (Komkor) Roberts Eidemanis, Roberts Eihe who shaped the creation of gulag system in Siberia and the former intelligence officer and Kolyma gulag commander Eduards Bērziņš [of Lockhart Plot fame]. There were so many people to be purged that on 31 January 1938 the Politburo extended the operation in this resolution:

To permit the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs to continue until 15 April 1938 the operation of annihilating espionage and sabotage contingents among Poles, Latvians, Germans, Estonians, Finns, Greeks, Iranians, Kharbintsy [people living in Harbin who had returned to the USSR after the Soviet government had sold the Chinese Eastern Railway to Japan] Chinese and Romanians, including foreign nationals as well as Soviet citizens.

Among the senior and significant Latvians executed were:

Mārtiņš Lācis: One of the founding fathers of the Cheka, Lācis was arrested in November 1937, accused of membership of a Latvian counter-revolutionary, nationalist organisation and shot in Moscow on March 20, 1938.

Jēkabs Peters: the veteran Cheka man was chief of the Eastern Department of the GPU when he was arrested in April 1938 during the Great Purge. He was executed at the Kommunarka Shooting Range in Moscow on April 25.

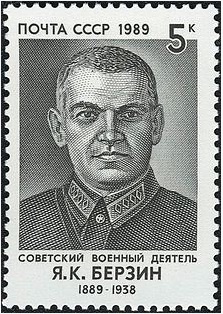

Jānis Bērziņš: A product of the revolutionary times, Bērziņš (Nov 1889–July 1938) led a guerrilla unit in the 1905 Revolution in Latvia, was wounded, captured and sentenced to death, but because of his age he was deported to Siberia. He escaped, joined the Russian Army and deserted in 1916. Joining the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution, he reached the rank of General and Chief of the Latvian Red Army. He was one of the principal organisers of Lenin’s Red Terror, persuading deserters to return by shooting hostages and viciously putting down peasant rebellions, and was a key figure in the crushing of the rebellion by Kronstadt sailors in 1921. He served as Head of the Military Intelligence (the GRU) from 1920 to 1935 and was sent to Spain as a military adviser in the Spanish Civil War. He was recalled during the Purges, arrested and shot on 29 July 1938 in the cellar of the Hotel Metropole.*

Jānis Rudzutaks was born near Saldus in Courland, the son of farm workers. In 1903 he got a job in a factory in Rīga, and joined the Latvian Social Democrats in 1905. He was arrested for his political views in 1907 and sentenced to ten years’ hard labour, finishing his sentence in Moscow just after the February 1917 Revolution. He became an important Communist Party administrator and close friend of Lenin’s. Appointed deputy chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars in 1926 he held the position until 1937, when he was accused of Trotskyism and spying for Nazi Germany and arrested. He was found guilty and shot on 29 June 1938, aged 50.

Jēkabs Alksnis: born in January 1897 the son of a labourer in Livonia, Alksnis became a member of the Communist Party in 1916. He graduated in 1917 from the Odessa Officer School and went to the Western Front where he was active in revolutionary work among the soldiers during the October Revolution. He joined the Red Army in 1919, becoming a military commissar in the Orel district. After two years at the Mikhail Frunze military academy he became deputy chief of the Soviet Air Force and, from January 1937, deputy people’s commissar of defence for aviation. He died on 29 July 1938.

Ivars Smilga had initially been a friend of Stalin’s but he became a convinced anti-Stalinist in 1927. He led opposition rallies and was deported to Siberia despite large crowds protesting at the station as he was bundled aboard a train into exile. After Leningrad party boss Sergey Kirov was assassinated in December 1934 Smilga was arrested and sentenced to 10 years in prison. In January 1937, he was brought to Moscow from prison on the eve of the Second Moscow Trial. Despite being severely tortured, he refused to testify against others or plead guilty and was shot on 10 January.

Vilis Knoriņš: born August 1890 in Līgatne, Cēsis. Became involved in the revolutionary movement in 1905 and joined the Communist Party in 1910, contributing to newspapers in St Petersburg, Rīga and Liepāja. After the February Revolution in 1917 he organised Bolshevik groups among soldiers on the Western Front and among workers in Minsk, and during the October Revolution was a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee in the Western Region. He became agitprop director first in Moscow then to the Central Committee, and was a member of the Pravda editorial board from 1932–34, Bolshevik 1934–37 and director of the Institute of the Red Professoriat, which dealt with party history. He was shot on 29 July 1938.

Roberts Eihe: born July 1890 in Dobele and a Communist Party member from 1905. The son of a farmhand, he became a metalworker and joined the Social Democrats in Latvia in Jelgava. He left for London in 1908 and returned in 1911, becoming a member of the Central Committee of the SDLT. He was exiled to Siberia but escaped and joined the Rīga soviet. He became Commissar for Food in Soviet Latvia in 1919 and when that fell he joined the Soviet administration working in Siberia. In October 1937 he became People’s Commissar of Agriculture. He died on 2 Feb 1940.

Roberts Eidemanis: From Lejasciems in Gulbene, he joined the Bolsheviks in March 1917 after the February Revolution and took part in the Red seizure of power in Siberia. He led his troops against the Czechoslovak Legion in Omsk and all three White generals, Krasnov, Denikin and Wrangel, then in Ukraine against Nestor Makhno’s Anarchist Black Army. After the Civil War he was a commander at the Frunze War Academy and chairman of the Latvian Writers’ Central Office, as well as a member of the Prometheus Society. He confessed under torture to being a part of the ‘Latvian underground military-fascist conspiracy’ and was tried in secret alongside Marshal Tukhachevsky and the generals Iona Yakir, Ieronim Uborevich, Vitaliy Primakov and others, and was executed in June 1937.

Kārlis Baumanis was the son of a farmer in the Vidzeme region near Limbaži. He joined the Latvian Social Democrat party in 1907 following the 1905 revolution and was jailed for membership of an illegal organisation. On his release he went to study in Kiev and after the Civil War was an influential figure in the Communist Party Central Committee, becoming First Secretary in 1928 and then standing as a Politburo candidate. However, he was blamed for the failures of collectivisation, discharged from the Moscow committee and sent to run the Central Asian bureau. In April 1937 he was suddenly dismissed from his position and in October arrested and imprisoned at the NKVD Lefertovo jail. He was shot after two days of ‘merciless interrogation’.

In Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn gives a frightening insight into what Cheka interrogation during the purges might mean. Prisoners were suspended from ceilings by the tips of their moustaches, packed into cork-lined cells with the heating turned up full until blood oozed through their pores, stretched out in a cell with guards on each limb as a Cheka officer pressed harder and harder on their testicles with his boot – or beaten to a pulp with nightsticks and blackjacks until internal organs ruptured. That was if the tried and tested method hadn’t worked, he writes: the revolver on the desk.

The frightening revolver lies there and is sometimes aimed at you … as the interrogator … shouts: “Come on – talk! You know what this is about!”

Stalin’s extermination of political opponents, former comrades and even friends relied on having blindly obedient, brutal or unbelievably cruel subordinates. One such man was Leonid Zakovsky, a Latvian from Liepāja who was head of the Cheka in Leningrad. Here, up to 47,000 Latvians, Poles, Finns and Estonians were shot on the orders of Cheka boss Nikolai ‘Yasha’ Yezhov in the purges of 1937 and 1938, with Zakovsky doing much of the dirty work.

Born Henriks Štubis in 1898 into a family of lumberjacks in Aizpute in Courland and schooled briefly in Liepāja, Zakovsky became a Bolshevik in 1913 and was recruited by Dzerzhinsky to be a founder member of the Cheka.

As Robert Conquest notes, Zakovsky famously said that he could:

make Karl Marx confess to being an agent of Bismarck: qualities demonstrated in the torturing and framing of his old comrades, in a manner which illuminates much sentimental nonsense about the brotherhood of the revolutionaries, the pure-heartedness of the Old Bolsheviks.

He ran a special Cheka department in Moscow between 1918 and 1920 and was a Cheka spy during the Civil War, then ran the Cheka’s successor, the GPU, in Ukraine from 1923 to 1925. He became head of the State Political Directorate, the OGPU, in Siberia, taking charge of Stalin’s security during his mission as General Secretary there in 1928. After two years as security chief in Belarus between 1932 and 1934, he became head of the NKVD in Leningrad, ten days after the murder of Sergei Kirov on 1 December 1934.

He ran the repressions that followed Kirov’s death, distinguishing himself by his cruelty, using the whip freely. During the Yezhov purges he beat evidence out of his former associates.

Cheka agent Alexander Radzivilovsky took part in these operations.

I asked Yezhov how to carry out in practice his directive on exposing the anti-Soviet Latvian underground. His reply was that there was no need to feel embarrassed by the absence of concrete material, but I should mark out several Latvians who were party members and beat the necessary statements out of them.

‘Don’t beat about the bush with this lot, their cases will be decided in batches. You need to show that Latvians, Poles in the party are spies and saboteurs etc.’ (Yezhov’s deputy) Frinovsky recommended that I should, in cases where I failed to get confessions from detainees, sentence them to shooting just on the basis of indirect witness evidence or simply unchecked informants’ materials.

Stalin’s Great Terror was a carefully organised 18-month campaign of repression that began in July 1937, targeting enemies of the regime and political opponents [Order 00447 led to the arrest of 31,339 kulaks, White Army officers, priests, Socialist Revolutionaries] and then nationalist minorities such as Latvians, Greeks, Romanians, Finns and Estonians. The terror in Leningrad, dubbed the Yezhovschina after the NKVD chief, involved ‘cleaning up’ anti-Soviet elements already in detention. The victims were buried secretly at night in the Levashovo cemetery in Leningrad. It is now a focal point for remembrance of Stalin’s victims.

Zakovsky gave the order to shoot 1,111 prisoners in one of the first gulag camps, on the Solovky islands in the White Sea. They were executed at Sandarmorkh on 16 October 1937. He was rewarded well for his loyalty, decorated with the Order of the Red Banner and the Order of the Red Star in 1936 and the Order of Lenin in 1937. He was elected a member of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR in December 1937. On 19 January 1938 he left Leningrad for Moscow where he became deputy to Yezhov, the People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs, and head of the NKVD for the Moscow region until March 28, 1938. When Stalin removed the previous Cheka boss Genrikh Yagoda, he ordered Yezhov to purge the intelligence services. Of Yagoda’s 110 most senior men, ninety were arrested by Yezhov. Most were shot. Yezhov arrested 2,273 Chekhists and, on his own count, dismissed 11,000.

Yezhov’s deputy, Mikhail Frinovsky, was another ruthless and cunning veteran Chekhist. He oversaw the interrogation of Yagoda and the murder of the head of the foreign intelligence and spy network, Abram Slutsky. Slutsky was asked to report back to Moscow in February 1938 on the achievements of his team. Frinovsky called in two other NKVD agents, Zakovsky and Mikhail Alekhin, head of operations and a specialist in poisons. There are two versions of what happened next. In one, over a cup of tea, Zakovsky offered a box of chocolates. Slutsky bit deep into his – only to be dead within moments. The chocolates were filled with potassium cyanide. With Slutsky slumped dead in an armchair, Frinovsky told his fellow NKVD officers that a doctor had diagnosed a heart attack, but the more experienced among them recognised the tell-tale blue spots of cyanide poisoning. In the alternative version, Zakovsky jumped Slutsky from behind and placed a chloroform-soaked cloth over his face, while Alekhin injected poison into his arm. Either way, Slutsky ended up dead.

In August 1938 Stalin announced that Frinovsky would be replaced as deputy NKVD boss by Lavrentiy Beria. Fearful that Zakovsky would give evidence to Beria against him, Frinovsky moved quickly before his replacement took over. On 29 August 1938 Zakovsky was arrested, accused of being an agent of the Polish and German counter-espionage and shot.

Beria took over in September and succeeded Yezhov in November. In February 1939 Alekhin was shot. Beria submitted a list to Stalin of 346 people recommended for execution. Yezhov, Frinovsky, his wife Nina and son Oleg were on it. Yezhov was shot minutes after his appeal against his death sentence was refused. He had to be dragged weeping and screaming to the wall where he was shot. Frinovsky was executed on 8 February 1940.

* Alongside him was one of the leaders of the October Revolution, Joseph Unshlikht, a Polish nobleman and Social Democrat Party leader, considered one of the first founders of the Cheka, which he joined after the Bolshevik seizure of power. He formed a Revolutionary War Council in 1919 to organise a workers’ uprising in Poland which failed with Soviet defeat in the subsequent Polish-Soviet war (1919–1920) ended by the Peace of Rīga in 1921. A supporter of the Red Terror, he was deputy chairman of the Cheka from 1921–1923, dealing with the Tambov revolt and the insurrection in Ukraine. He was a Central Committee member for many years and deputised for Bērziņš while he was in Spain.

Taken from Up Against the Wall: The KGB and Latvia, published by Helion

Vincent Hunt is a former BBC reporter and documentary maker turned historical journalist, whose books showcase the voices of people who were there to tell the story of dramatic and often-overlooked episodes of history, beginning with the scorched earth destruction of northern Norway in 1944 (Fire and Ice – the Nazis’ Scorched Earth Campaign in Norway, The History Press, 2014) leading into a focus on Latvia’s tortuous and turbulent 20th Century. This began with a journey across Kurzeme in western Latvia, charting the six battles of the Courland Pocket in Blood in the Forest – the end of the Second World War in the Courland Pocket (Helion, 2017); analysing Latvia’s twisted relationship with the NKVD/KGB in the first book to examine this connection and its brutality (Up Against the Wall – the KGB and Latvia (Helion, 2019)) and leading to his most recent book following the Latvian Legion’s 15th Division across Pomerania (The Road of Slaughter, Helion, 2023). He continues charting the fate of this unit in Escape from Berlin – the Incredible Journey of the Janums Battle Group April 1945 (Helion, 2025) and Sent to Die in Berlin – the Latvian 15th SS Reconnaissance Battalion, 20 April-8 May 1945 (Helion, 2025: Helion & Company | Military History Books).

© Deep Baltic 2024. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.