Last year, British photographer Richard Schofield set up the International Centre for Litvak Photography in Kaunas, Lithuania’s second-largest city, as a way of preserving remnants of the city’s often-ignored Litvak (Lithuanian Jewish) history. Schofield’s interest in the subject developed after a chance discovery of a set of over a hundred photos, most of which were of the same Kaunas Jewish family. Later this year, the story of the family will be set to music in The Kaunas Requiem, a piece by the Ukrainian composer Anton Degtiarov inspired by their story. Deep Baltic caught up with Schofield to find out more about the project and the history of Judaism in Lithuania.

Why Kaunas, rather than the more obvious Vilnius – which was, after all, once known as “the Jerusalem of the North”?

Why not Kaunas? I didn’t originally move to Kaunas for ‘Jewish’ things, incidentally. To answer the question in more general terms there are several answers, the most interesting for me being that just because something is more well known than something else it doesn’t make it any more fascinating or relevant. Another answer would be that Kaunas during its famous ‘Golden Age’ between the wars was very much a Litvak city. When Lithuania became independent at the end of the First World War and Poland occupied the Vilnius region and Kaunas consequently became the temporary capital, there were almost no ‘ethnic’ Lithuanian architects, property developers or the like. During the 1920s especially, Kaunas was transformed from a small Russian military outpost with dirt roads into a modern city, with more than a little help from the city’s Jewish community. And then the Litvak population (of over 30,000, at least a quarter of the population) vanished almost overnight, leaving the city unfinished. Kaunas is frozen in time in many ways because of this.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BS5s9mdMjHc&w=420&h=315]

Kaunas in 1928

There are plenty of other reasons too, such as the Ryanair hub at the airport, the cost of living and the fact that the future is less well mapped out than it is in Vilnius. Then of course there’s all the weird stuff, like the thing you’ll get told sooner or later if you spend enough time in Kaunas that in 1976 they built a new television mast on top of the hill in Žaliakalnis that accidentally picked up television signals from Poland, whose slightly more liberal regime allowed such things as Fellini films to be shown on television. An entire generation in Kaunas grew up on Fellini whereas all they had in Vilnius were Soviet films.

You say on the website you “unearthed” these photos. Could you elaborate on this a little bit? Where was it?

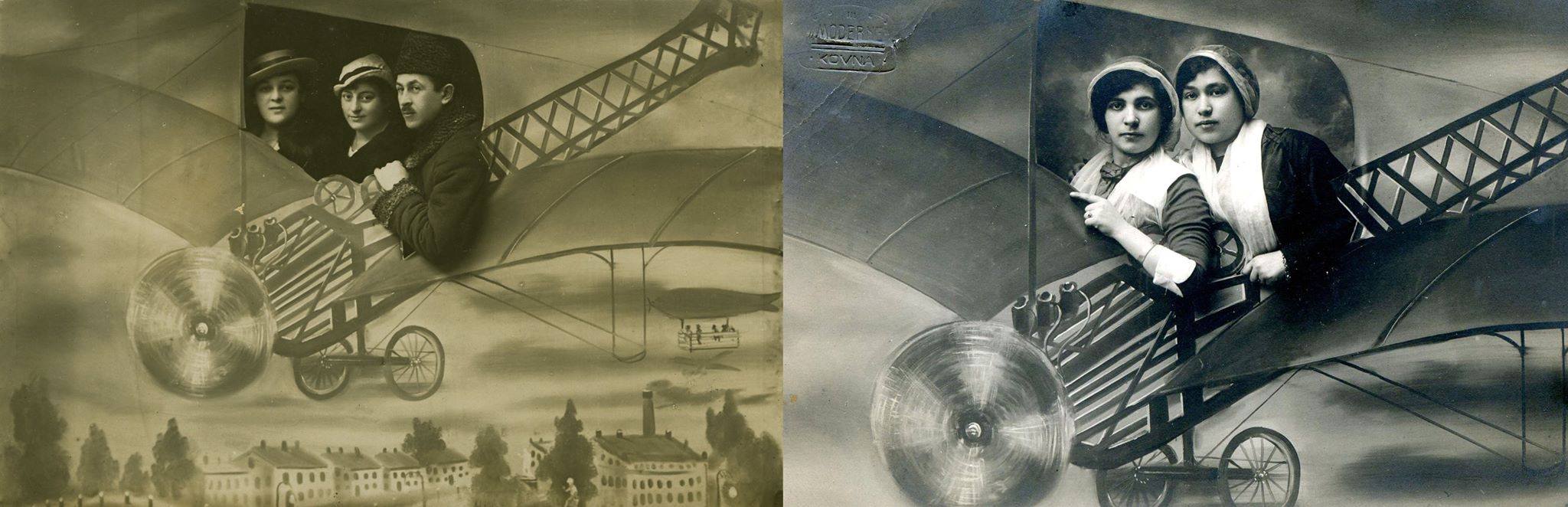

I was doing some research in Sugihara House [set up in honour of the Japanese diplomat who saved thousands of Lithuanian Jews by issuing them with visas before the Nazi invasion] in Kaunas in 2013, and leaning against one of the walls in their small library were half a dozen or so large picture frames with old black and white photographs in them. I was intrigued and asked what they were. It turned out they once belong to an unidentified Litvak family from Kaunas who managed to smuggle them out of the Kaunas Ghetto before it was liquidated during the summer of 1944. I immediately saw their historical importance and was horrified to discover they were in the possession of a local politician who not only failed to understand the importance of the photographs but who also hadn’t scanned them. I felt they were really in danger of being lost or stolen or burned to ashes and spent a year and a half trying to get them digitised. This finally happened with the help of a couple of locals and the United States Holocaust Museum.

What brought you to Lithuania in the first place?

This can be traced back to a drunken conversation about Fidel Castro in a cocktail bar in Bucharest in October 1999 with the then editor of Bucharest In Your Pocket. I was spending a lot of time in Havana and my temporary drinking partner suggested I write Havana In Your Pocket. I didn’t write that, but I did write a short guide to the underground world of Havana I knew and moved around in and sent it to Bucharest for fun more than anything else. The guide did the rounds and soon people at In Your Pocket started writing to me offering me jobs. I accepted an offer at Vilnius In Your Pocket because I knew nothing about the place, and the rest as they say is history.

Do you think modern Lithuania deals with its Jewish history in a satisfactory way? How could it improve if not?

I can’t think of a single country anywhere in the world that does a particular good job at dealing with its history. Most nations have embarrassing historical moments they’d rather forget, and Lithuania is no exception. When something particularly outrageous occurs I get active, but I prefer to do things independently and show through example. This is why I founded the International Centre for Litvak Photography. One thing that is annoying me at the moment is a street in Kaunas named after Kazys Škirpa, a personal friend of Adolf Hitler and one of the leading architects of the Holocaust in Lithuania. I’m in the early stages of a campaign to get the street renamed, and am taking it all very slowly. Like most of the bad things happening in Lithuania at the moment, the root of street name problem isn’t evil as many people like to think. It’s stupidity.

You mention on the Facebook page that the monument to the Kaunas ghetto is a “single [and] embarrassingly small monument”? Do you think this is a deliberate snub by the city government?

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think that monument was the work of the Jewish community. The local Jewish community (or rather communities) are also aware of the dreadful condition of the Old Jewish Cemetery in the city and do nothing about it (things are set to change with this incidentally, thanks to an initiative begun by a Lithuanian Jew living in Belgium and implemented by the municipality). They were also aware of the photographs I unearthed and did nothing about trying to preserve them. Yet another reason why I started the NGO.

It’s interesting to see on the Facebook page how people are cooperating to identifying family members and places, and parsing handwritten text. Would you say there is a lot of local interest in Lithuania? Why do you think this is if so?

Most of the help I’ve received with that has come from Litvaks living abroad, ones that were born in Lithuania during the Soviet occupation and who left as soon as they could. This is one of my ‘things’ at the moment, i.e. the untold story of the final chapter in the centuries-long historical Litvak narrative. It’s common knowledge that around 95 percent of Lithuania’s more than 200,000 Jewish men, women and children died in the Holocaust, a horrendous statistic that overshadows the five percent who survived. One of the projects the NGO is working on at the moment is an archive of Litvak family photography from the post-Holocaust Soviet period. There’s no official record, so these documents are pretty much the only evidence there is that Litvaks lived in Lithuania in relatively large numbers after 1944 compared to the country’s tiny population today.

How much have you found out about that first family whose photographs you discovered?

Not much to be honest. A few names from the hand-written messages on the photographs, but of course these messages reveal little of any scientific use as they were sent to people they already knew. First names mostly. The biggest thing we’ve uncovered so far is the fact that the family were musical. There are references throughout the collection, plus there were other documents as well as the photographs that were smuggled out of the Kaunas Ghetto, some of them of a musical nature. This is really why I commissioned The Kaunas Requiem. Did you know there was a Kaunas Ghetto Orchestra and that a Litvak incarcerated in the ghetto built a camera and took photographs of some of the performances? It’s a tantalising thought that the family attended these concerts.

What would you say particularly distinguishes Litvaks and Litvak culture from other forms of Judaism that existed in Eastern Europe?

Not all Litvaks were religious. In fact, Judaism is pretty much the only thing that the Jews of the world have in common. They speak different languages, eat different food, wear different clothes etc. It’s really only inside Judaism that they all ‘meet’ as it were.

A direct quote from Vilnius In Your Pocket, written by me a few years ago…

‘Lithuanian Jews can be traced back some seven centuries. The classic Lithuanian Jew (Litvak) is known in folklore for a love of education, no-nonsense straight-talk and a sharp wit. Jews were settled from an early date in Vilna, as the capital was and still is known in Jewish culture (more precisely in Yiddish as Vilne).’

Like the definition of a Jew in general, the definition of a Litvak is different depending on who you ask. In general, when a Litvak speaks of Lithuania they’re referring to a large territory of land that roughly corresponds with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Thus are Marc Chagall (born in today’s Belarus) and Mark Rothko (born in today’s Latvia) considered by many to be Litvaks. Some Jews also insist that the region’s Hasidic Jews are not Litvaks.

The only concrete thing that you could argue bound the Litvaks together was Yiddish, although this changed with the advent of Zionism, when those who became Zionists began speaking Hebrew.

A small number of Jews did remain in Lithuania after World War II and the Holocaust. What would you say characterised the Jewish experience during the Soviet occupation?

Most survivors remained, and of course many of these went on to have families. This is actually my specialist subject, one that’s almost completely been forgotten. The first and most important thing to remember is that there was no universal treatment of the Soviet Jews. It was much harder to be Jewish in Soviet Russia for example than in was in Soviet-occupied Lithuania, where, after the 1956 Thaw, the Soviet authorities actually allowed Jewish cultural institutions to exist, one in Vilnius and the other in Kaunas. I’ve done quite a lot of research into Litvak life and culture in Kaunas during the Soviet period, and have discovered some amazing things. Ultimately though, freedom to be anything other than a good Soviet citizen was always at best frowned upon by the Soviets, and so the overriding narrative is one of a mass attempt to escape. The Holocaust massively reduced the Litvak population, and this figure of 95 percent, for no fault of its own, completely overshadows the five percent who survived. Had the Soviets not reoccupied Lithuania in 1944, it’s extremely likely that the Litvaks would have carried on as before and rebuilt what was left of their communities. Unfortunately this never happened. The Litvaks slowly left Soviet-occupied Lithuania, and, during the late 1980s, when it was easy to leave, most did so. The Kaunas-born Israeli historian Dov Levin, who survived the Kaunas Ghetto, explained it very clearly when he wrote something along the lines of ‘the Nazis took the bodies and the Soviets took the souls’.

Could you expand upon your comment that “it’s not evil but stupidity” that’s behind the problem of naming streets after anti-Semitic figures?

Difficult! It has to be stupidity because most of the people who defend these things aren’t bad people. A friend was at an event recently where there was a heated discussion around these issues and someone suggested that many Lithuanians find it difficult to differentiate between the legal and moral aspect of things. This may well be the answer. From my own perspective, I see that many Lithuanians fail to grasp the fact that an individual can be both a victim and a perpetrator. Thus, many of these names are justified because the people involved fought the Soviets and are therefore heroes. The fact that some also participated in the Holocaust is conveniently overlooked, or, worse, folded into the absurd notion of the Jew-Bolshevik. Interestingly, this year also marks the 75th anniversary of the first Soviet deportations from the Baltic States. In the case of Lithuania, it’s now universally believed among experts of all persuasions that at least 20 percent of Lithuanians deported in June 1941 were Litvak. This is the highest percentage per capita of all ‘ethnic’ deportation figures. So maybe I could add the word ‘ignorance’ to stupidity. People in my experience are not aware of the facts. This is not exclusively a Lithuanian problem incidentally. Look at what’s happening in the UK at the moment. And then there’s the Trump supporters in the United States.

Is this project much of a break from your previous photographic works?

It’s certainly different! I do also curate work, although I haven’t done a lot, just a couple of exhibitions in the UK. The word break is an interesting one. Is it a break, or is it a logical progression? It’s probably a diversification. As much as I love curating, I also like taking photographs and working on my own projects. I am also doing this by the way. It’s just not as newsworthy at the moment.

What would say is the biggest challenge you have faced so far in the project?

The only real challenge we’re facing is a financial one. We need to raise quite a lot of money to do the exhibition/installation in September and to date have failed to do so. We’re confident that we can reach the target, but we are depressed at the apathy that’s been shown towards the crowdfunding campaign. I’ve no idea why this is, although I do get the impression that when someone clicks ‘Like’ on a Facebook page they feel they made some kind of contribution. People are very strange sometimes.

What are your ambitions for the future?

In the short- to medium-term, the NGO is currently trying to buy at abandoned synagogue in Kaunas and turn it into a combined gallery, museum, community space, archive and educational centre. This is going to be fairly all-consuming. Other than that I want to go back to my own work. Just me and a camera and some interesting ideas.

The two curatorial exhibitions I did in the UK were about family photography inside the USSR. One of the things our NGO is now doing is creating a digital archive of Litvak family photography from the post-Holocaust Soviet period. There is no other record of this, so it’s quite an important project.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vp8bubipw2E&w=560&h=315]

Later this year, the story of the lost family will be set to music in The Kaunas Requiem, a piece by the Ukrainian composer Anton Degtiarov inspired by their story. Schofield told us a bit more about the background and significance of the piece.

An as yet unidentified Litvak family from Kaunas were imprisoned in the Kaunas Ghetto. In their possession were family photographs and other documents which they managed to smuggle out and into the possession of a Lithuanian family shortly before the Kaunas Ghetto was liquidised in the summer of 1944. We have no idea what happened to the family, although the fact that the archive is still in the possession of the Lithuanian family strongly suggests the Litvak family never survived. Writing on some of the photographs suggests that there were strong musical connections within the family. A woman called Anna, who we think was the mother (or possibly grandmother) of the family, was a singer, although we can’t deduce whether she was a professional or an amateur. She also might have been a teacher. Other documents smuggled out include a programme of classical music performed in Vilnius in February 1940. One of the names of the performers (a female singer) is similar to other names that appear on the photographs. You have to ask yourself why a family would smuggle this programme out. It must have been important.

There’s also the story of the Kaunas Ghetto Orchestra, which incidentally was photographed by a Kaunas Ghetto prisoner called George Kadish. This is an amazing story in itself, but for the purposes of The Kaunas Requiem it’s tantalising to assume the family attended these concerts. Unfortunately, George Kadish seems to have only photographed the orchestra and not the audience, so we’ll never have the chance to see whether members of the family were at any of the concerts. All of this information made it obvious to me that a fitting way to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the establishment of the Kaunas Ghetto in 2016 would be to commission a piece of music inspired by the photographs. The music incidentally is made up of three layers, a composition by our Ukrainian composer [Anton Degtiarov] and two more layers made from field recordings we made in a market, a brewery and of a Singer sewing machine dating from 1877. These recordings represent traditional Jewish trades and will be treated and looped and otherwise manipulated and mixed into the composition. A short segment of the composition, which if played in its entirety lasts for 75 years, will be ‘performed’ (by a computer) over a seven-day period in September along with the photographs and other documents relating to the project. In keeping with Jewish law, no industrial sounds will be played on the Saturday section of the performance. Likewise, the market recordings will be switched off on the Monday, the traditional day when markets are closed in Lithuania. The other element involves a database of names of Holocaust victims from Kaunas, that we’re feeding into a computer and converting into sounds.

Thus the music will also involve a Reading of the Names event, something that’s becoming more popular every year and an innovative way of doing it in keeping with how our NGO likes to work. As well as producing something unique and different, we’re also using the project as a way of trying to identify the family. We’ve already received some interesting emails from the United States on the subject, of which you can read more about on our Facebook page. We’re extremely aware of the fact that Kaunas’ pre-war Litvak population featured individuals who were years ahead of their time, relatively speaking. Some of them studying in Paris, some of them playing in jazz bands, etc. We think it’s interesting to imagine, had the Holocaust and Soviet occupation not taken place, what kind of art the descendants of these people would be making today. We’re also very aware of the fact that most education relating to Litvak history and culture taking place in Lithuania today is old-fashioned and of no interest to today’s young generation of Lithuanians. Take a look at the Facebook pages of the various Jewish institutions in Lithuania, in particular the photographs taken at their public events. The people who attend these events are mostly elderly. Who will attend them in 20 years’ time? Unless people start giving young people what they want rather than what older people think they should receive the memory of Lithuania’s Jewish past will be lost.

As this article goes to press, we have received notice from Richard Schofield that the family in the photographs has probably been identified. Check the International Centre for Litvak Photography’s website and Facebook page for further updates.

All photos credit – the International Centre for Litvak Photography unless otherwise indicated

© Deep Baltic 2016. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.