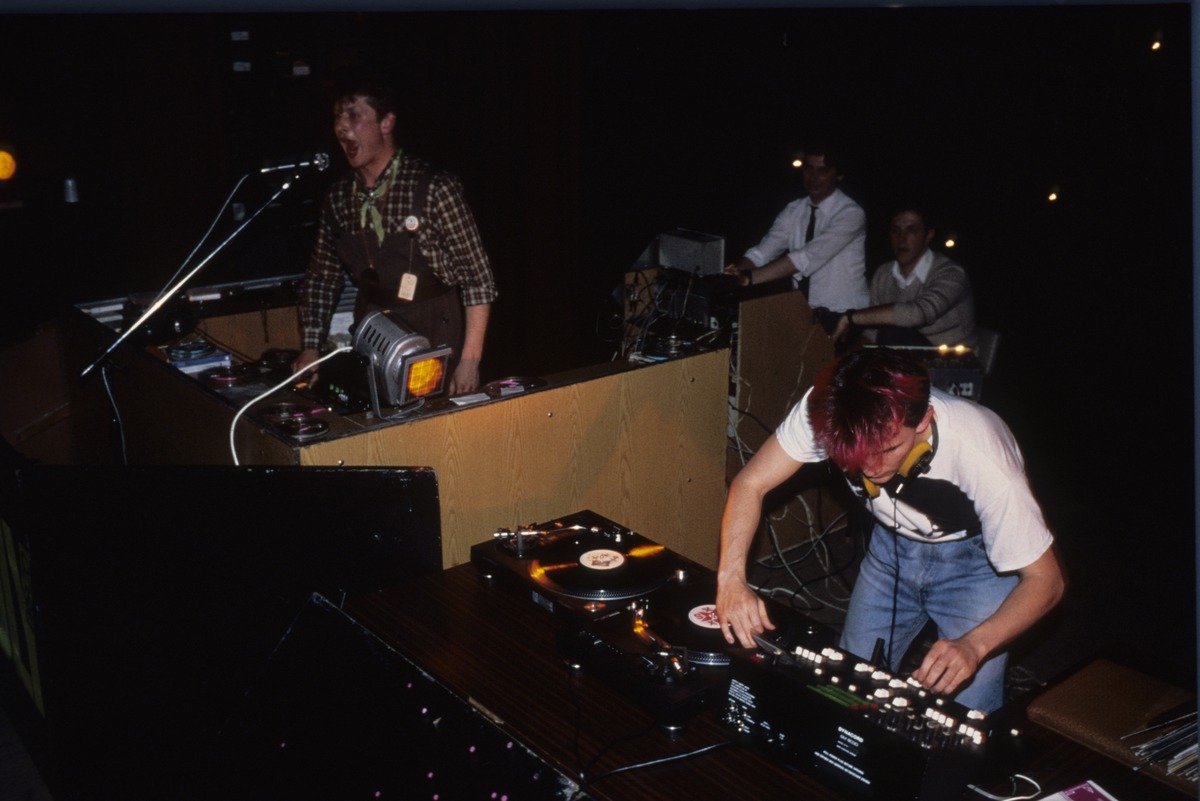

A new Latvian/Russian documentary film, Deju Laikmets (Era of Dance) tells the story of how the techno explosion of the ’80s was brought to the Soviet Union – via Riga, in a most unexpected way. It is above all the tale of one extraordinary, and often overlooked man: Indulis Bilzens, born in Riga in 1940 but raised in West Germany after his father was deported to Siberia and his mother fled the Soviet invasion. Having studied electronic composition in Düsseldorf, become involved in the British peace movement while studying at Cambridge University and worked for a number of German newspapers, Bilzens began to visit his homeland, still under Soviet occupation, in the late ’70s. A friendship with the German DJ Maximilian Lenz (who plays under the name WestBam, taken from a name Bilzens gave him – “Westphalia Bambaataa”) led to an interest in the new electronic music coming out of the US. Bilzens and Lenz made repeated visits to Riga in the late ’80s, introducing DJ culture to a curious, and increasingly enthusiastic Latvian audience, but being viewed with decided suspicion from official quarters – including the KGB.

As well as Lenz and Bilzens, now in his mid-’70s, Era of Dance features regular talking head contributions from US techno pioneers Derrick May, as well as Russia’s leading music critic Artemy Troitsky, resident in Riga for much of this period, and also focuses on local talents who were active during this period, most prominently Roberts Gobziņš (who took the name Eastbam).

Thanks to these personalities, Riga became one of the centres of techno music in the Eastern bloc, developing a distinctly individual take on the sound sweeping the world. It took several years before the sound truly caught on to the east of Latvia, meaning that for a few years, Riga was, as Troitsky puts it in the film, “the nest of DJing culture for the whole USSR”.

Deep Baltic’s Will Mawhood spoke to Viktors Buda, the director of the film, about this fascinating period in Riga’s history.

So when did techno reach the Baltic states, and how did it get there?

Techno first appeared in the Baltics in 1986. The Baltic countries have always been a bridge between the West and Eastern Europe – this was true even in the Soviet era. In the context of the history, all of us were more attracted not to the fact that it came first, but the personal story of the heroes themselves in this historical adventure… Our movie will show more details about this story.

What was the attitude of the Soviet authorities? This must have been very different from any youth movement they had to deal with previously.

If we talk about Latvia in the Soviet times, Riga was the closest you could get to the West. Different people regarded the new innovations in different ways. One part of society categorically refused to accept anything new. The other part was interested and involved in the new movement. Communicating with witnesses and participants in those events, it became clear that the Soviet authorities didn’t really understand what this movement of electronic music represented. I think the arrival of techno culture was justified more by the lack of information from the Soviet authorities than their precise position.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=neFFjQj-CGU&w=560&h=315]

Many people might be surprised to know that one of the key influences on dance music in Latvia came from a man already in his late 40s at the time when the scene started to develop, Indulis Bilzens. Could you tell me a bit about his story?

His life story is worthy of being filmed. Bilzens is one of the most important and, at the same time, underrated people of the last decades. He is a man of the era.

I would say he is one of the most notable cultural diplomats of the ’80s and ’90s. He has been connected with the sphere of electronic music since the end of the ’60s when there was no DJ culture. In fact, he became one of the first outsiders who entered into the electronic music environment. Here it’s worth mentioning Cologne in the ’60s and the University of Düsseldorf, which at that time was almost the only university where it was possible to study electronic music machines and their structure. Bilzens as a historian of culture was more interested in the principles on which to base this new innovation. The University of Düsseldorf from the end of the ’60s was a significant period because at this same university were studying a couple of guys who later became know to the world as Kraftwerk. They are not personally connected; however, they operate in parallel. Bilzens always knew how to influence to develop things and at the same time stay behind the stage curtain.

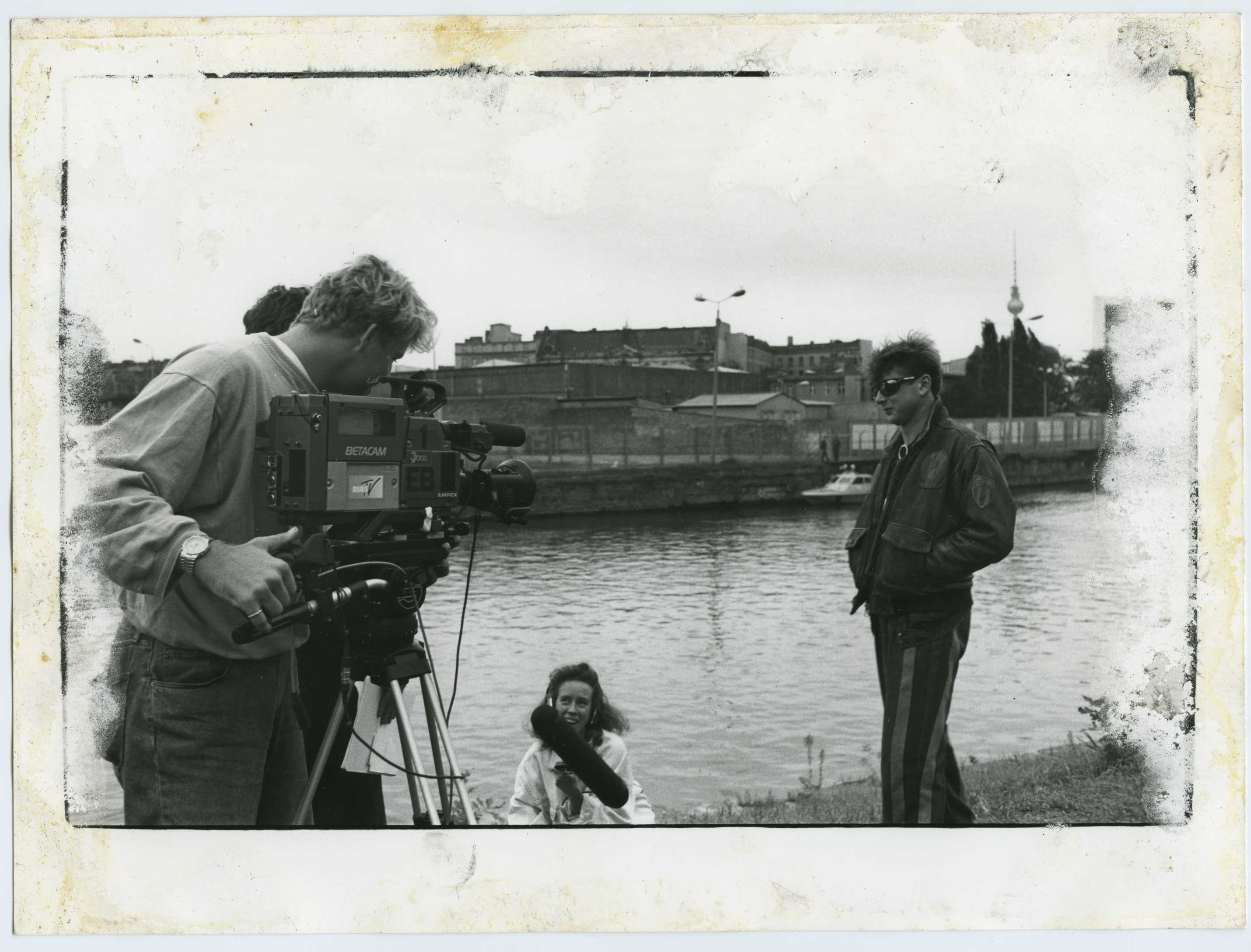

There’s a clear connection with Berlin in the film – and the time period covered obviously coincides with the fall of the Berlin Wall. Why was this city so important?

The second half of the ’80s changed everything. Berlin became the centre of Europe very quickly after the wall came down. What was happening in Berlin was considered influential and music has always reflected social phenomena that are present. But the story told in the film began much earlier and the early stages of any process always have a very special aspect.

The Latvian musician and artist Hardijs Lediņš, who we have featured previously on the site, was involved in the scene as well and features in the documentary – even though many think of him more as an art/avant-garde figure. What was his role?

He played an important role in the development of this electronic underground movement back then. I would say he was more avant-garde artist in the Soviet Latvian scene, more of an organiser – even though many think of him more as a godfather of DJ culture. For him, music was more a tool to realise his artistic ideas. We would now call his activities lo-fi or DIY. Hardijs was working in this style as early as the beginning of ’80s.

Is there a noticeable change in the scene between the mid ‘80s and the late ‘80s – when Latvia is increasingly operating like an independent state?

The second half of the ’80s was a rising time in many ways, not only because this new music culture came to Latvia, but also because it coincided with perestroika and the Latvian road to independence. In the first half of the ’90s, this cultural movement started to recede, driven by the acquisition of independence, the appearance of commercial radio stations and a massively increased inflow of foreign pop music, as well as other factors. That was until 1995 when it was reborn in a new form, which we called “rave” culture. Raves as we know them came to Latvia from Moscow in the mid-’90s as a new form of electronic music culture. This rave culture developed very quickly in Russia, but in Latvia during this period, following independence, all of society were more focused on building a new country (independent Latvia) and dance music scene remained stuck underground. This scene did not develop in Latvia until 1995, when rave culture came from Russia…

How far were people in Western Europe aware of what was going on in the Baltics? There is one clip in the film taken from a Dutch TV programme, about DJs in Latvia building their own synthesisers and equipment, and as you mentioned, there was clear awareness among many in Germany, but what about elsewhere?

Historically we built up a link with Germany. I don’t think that in other countries people were aware of what is going on here. Today, most people still do not know the history of this period, but they are interested in it. At the beginning of the production process, the film’s story only covered our post-Soviet space, but it was not enough to recreate a complete picture of the processes of the day. If we focused only on the local history of Riga or St. Petersburg, it would be interesting just for the heroes of the film and their friends. There would be no significant audience for a film of this kind today. It’s very difficult to realise a very local story in terms of production. On the shooting of this film we have had to spend a few years, as well as a lot of human and financial resources.

In the film Juan Atkins, one of the originators of Detroit techno, mentions that techno music was originally named “afro-futurism”, speaking to its roots in a mostly African-American scene based in cities like Chicago and Detroit. Is it surprising that a music from such a different geographical and cultural background caught on in the Soviet-occupied Baltic states?

It became a global phenomenon. Regarding the invasion of electronic music culture into the Eastern bloc, it was best said by Derrick May: when the Berlin Wall came down, it changed not only the scene, it changed the music. Because then came the eastern sort of energy, influence. It wasn’t creation, it was more like politics, anger, aggression and freedom at the same time. It opened up a revolutionary mentality for the whole generation.

The Russian rock writer Artemy Troitsky plays a key role in the film – how did he become interested in the scene, having previously mostly been associated with rock?

Artemy has had a very long relationship with Riga, and plays one of the key roles in the film. I felt some scepticism, especially from the Russian side, of him, but this can be explained by a lack of information – most people think of Troitsky as an expert on rock music. Most of [Russian] society does not know that Troitsky is also associated with the origins of electronic music in the Soviet Union..

In the mid-’80s, when Troitsky was banned in Moscow, he began his television career on Latvian TV and led the first Soviet programme dedicated to video clips – it was called “Video Rhythms”. Although Latvia was part of the USSR, aspects of social life were different. In Riga, Troitsky could afford to operate more freely than in Moscow where he was banned from magazines, newspapers and TV in the mid-’80s. He is currently in a similar situation in Russia [having been highly critical of Putin and the current Russian government]. He not only witnessed these historic events in Riga, but was later one of the active protagonists of techno culture in Russia. This is one of the features of Artemy. It seems to me he has always been in opposition to the ruling system.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wfOTQZ9WUP8&w=560&h=315]

Was there similar interest in dance music in the other Baltic states, or was it mostly concentrated in Riga?

Scenes formed of course also in the other Baltic countries, but it happened a bit later. Since the beginning of the last decade, the Lithuanian scene has been one step ahead of the other Baltic states, but speaking about beginnings Riga had luck with individual characters, and it was thanks to this that DJ culture began in Soviet Latvia

It seems that by the end of the film in the late ‘90s, the scene has become increasingly dangerous – not only in the Baltics, but possibly even more so in Russia. What was the cause of this?

We chose to build the story around the beginnings of the scene and the characters involved, rather than raves in the ’90s. Because we had on our hands a unique story and heroes behind. The ’90s scene in Russia is worthy of a separate film. In Russia, this action was of course much more intense than in the Baltic States. All these fast changes… If Russians go crazy, they go totally crazy.

The scene in the ’90s was a mirror of common social phenomena. Everyone remembers it differently. Some people almost didn’t feel the impact of organised crime; others were closely linked to it. It was such a time full of adrenaline and rapid changes.

If you have lived for 50 years in isolation and suddenly everything that was previously banned is authorised, most of society will be unable to cope. Something similar happened with the Soviet Union. Imagine that one day North Korea changes and the breath of a new world and electronic music culture is allowed to reach this land – sooner or later it will happen…

What memories do you personally have of the time?

I was only 11 or 12 years old when these historical changes happened. At the beginning of this music I did not quite understand this electronic sound, but I liked the energy that music had. Each of us remembers that period and how much it affected them from their own perspective. In those days music was definitely a new bearer of culture, but if at that time people were aware of culture through music, this is no longer the case. If it is then very little. Nowadays, music has become little more than substance. But this is my subjective opinion.

How did you become interested?

For me personally, the story began around 2002, when I was working in television and directing broadcasts about electronic music. I met a few heroes of the film and the first idea of the movie came up. I collected archive footage for twelve years but it was still just an idea until we came together with Ritvars (Ritvars Bluka – documentary cinematographer) and began to try to realise this project. As we both been a part of the electronic music scene in Latvia for years, the film for us became a chance to assemble the missing pieces of the puzzle. The whole four years of the filming process was very inspirational because I had the chance to meet and work with people I respect. Many of them were some kind of heroes for me in the 90s.

Riga is rich in culture and cultural celebrities, but as we all know Latvia is a small country and its population always feel proud about remarkable people from Latvia. And Riga-born Indulis Bilzens is considered a citizen of the world; by his contribution he made Riga great in people’s eyes.

What traces do you think exist of the scene in present-day Latvia? What are the main heroes of the film doing now?

Riga has always been open to everything contemporary. I think it’s just a wheel of progress.

For the young generation now it’s the time. The moment. The energy. Now is the future for them. Electronic music has always represented the future, and now we have entered the Gadget Age. The electronic world which was built in the ’70s and ’80s with innovative sound, installations, the first electronic art, etc., has expanded – maybe 50 times. But it has not caused some fundamental change in the quality.

It could be that this film will give the film’s heroes the possibility to meet again. Many of them have disappeared from the scene, but some are still active. This story, this film will give a chance to meet them again, and I think it’s wonderful!

Viktors Buda was the chief editor of the first Baltic dance music magazine, Flash. In the mid-2000s he was also well known as one of the leading promoters in Riga. Since 2009, he has been working with leading electronic music names in the dance music capital, Ibiza. His works have been published in major international dance music magazines such as DJ Mag, Dub Ibiza, Life Guide, Ibiza.ru, and others. Viktors is an editor and one of the founders of the new media platform, Ibiza Life, a magazine dedicated to Ibiza cultural life.

The Russian-language version of Era of Dance premieres in Moscow in March, and will be in cinemas across Russia from 23rd March. An English-language version is forthcoming, and international screenings will be announced. You can find out more information on the film’s website.

Header image – WestBam and Eastbam play in Riga, 1987

All images credit – Era of Dance (Deju Laikmets)

© Deep Baltic 2017. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.