by Siobhán Hearne, TALLINN

In the early 1900s, Tallinn had a reputation amongst medical experts as a city with a venereal disease problem. Second only to the capital of St Petersburg in incidence of syphilis and gonorrhoea, Tallinn outranked much larger cities in the Russian Empire in terms of infection, including Moscow, Warsaw and Riga.[1] In 1914, one physician claimed that one in ten Tallinn residents were infected with a venereal disease, and most apparently caught their infections following encounters with prostitutes in the city’s brothels.[2] Why were venereal diseases allegedly so widespread in Tallinn? In this piece, I trace explanations given by various contemporary observers and place Tallinn within the wider context of disease control across the Russian Empire.

In the final decades of the Russian Empire, prostitution and venereal diseases were interconnected in official and popular imagination. In 1843, the Ministry of Internal Affairs introduced the Empire-wide regulation of prostitution with the stated aim of preventing the circulation of venereal infection. This system of “supervision” (nadzor) was installed in cities and towns across the vast Russian Empire, from Liepāja to Vladivostok. Within the territory of present-day Estonia, dedicated medical-police committees were established to oversee the regulation of prostitution in Tallinn, Tartu, Narva, Rakvere, Võru, Pärnu, Viljandi and even Kuressaare.

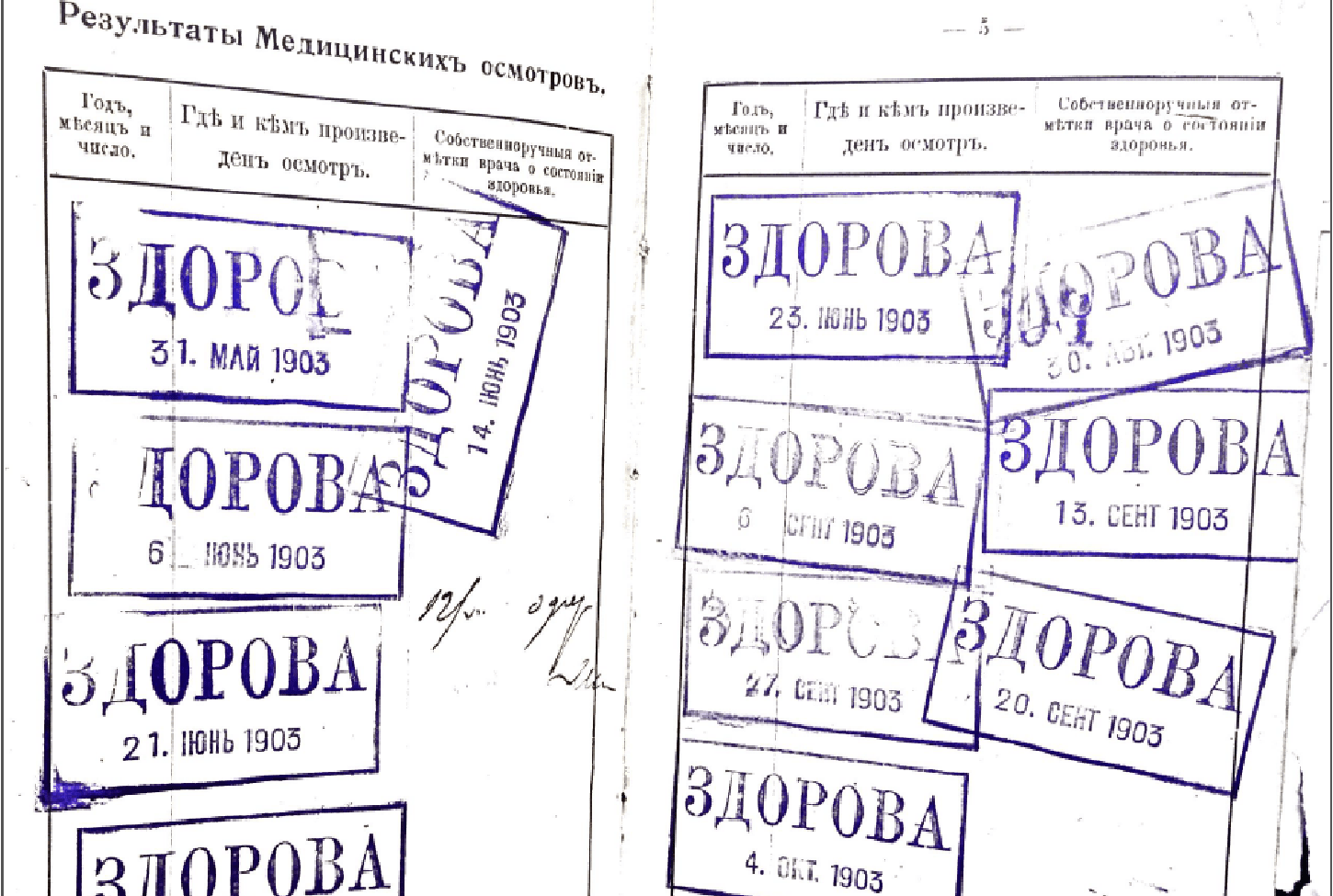

Under the regulation system, women who sold sex were required to register their details with their local police and swap their internal passports (documents required for travel and employment) for a new form of identification known as a medical ticket. Registered prostitutes were legally obliged to attend medical examinations twice a week, the results of which were recorded on their identification. If a woman was found to be infected with a venereal disease, she was supposed to go immediately to hospital for treatment.

The official aims of regulation were medical, but the additional rules that accompanied the medical ticket suggest that the tsarist authorities used regulation to limit the autonomy and visibility of women who sold sex. Registered prostitutes were forbidden from “obscenely” appearing in the windows of their apartments, disturbing and ‘enticing’ passers-by on the streets, walking together in public places, and even sitting in the stalls at the theatre.[3] They were also permitted to live only within specific city districts. Local police forces and the wider public were encouraged to root out women believed to be working illegally, known as “clandestine prostitutes” (tainye prostitutki). The authorities used regulation to police female behaviour, often conflating “promiscuity” with commercial sex and forcing women to register onto the police lists. As well as enforcing these rules, local police forces were required to issue licenses to brothel keepers and close down any rowdy or unsanitary brothels.

In 1909, Tallinn had a modest 7 state-licensed brothels and 181 registered prostitutes[4]. The city was hardly a centre of prostitution in the Empire, as it ranked 27th in terms of its population of registered prostitutes, which numbered just 2.7 per 1000 residents[5]. Five of Tallinn’s seven brothels were located on Martenskaia Street (now Mardi tänav), and these establishments bore the names Victoria, the Golden Star, Manchuria, Venice and the Manezh[6]. All but one of the original wooden brothel buildings were destroyed during the aerial bombardment of the city by the Soviet Air Force in 1944. The exception is number 3, which now ironically houses an AIDs information and support centre.[7]

The Russian imperial authorities endeavoured to monitor all women thought to be selling sex. This aim has left behind a rich historical record about the ethnicities, ages, and migration patterns of registered women, which makes them a unique group amongst the Russian Empire’s urban poor. We know that the vast majority of Tallinn’s registered women were classified as peasants and that over 95% had worked as domestic servants before they ended up on the police lists[8]. Most had worked as prostitutes for under five years, and had migrated to Tallinn from other towns or villages. The social composition of Tallinn’s registered women corresponded to the general picture across the Russian Empire. Registered prostitutes were predominantly lower-class migrants who sold sex for a short period during their twenties and thirties.

The ethnic composition of Tallinn’s police lists transformed as the city became better connected to other regions of the Empire. The Baltic Railway was established in the 1870s, connecting northern Baltic cities such as Tallinn and Tartu with the capital of St Petersburg[9]. The line was bought by the imperial Russian government in the 1880s and improvements were made to the route throughout the following two decades until it was finally absorbed into the North-Western Railway in 1906[10]. Before the amalgamation of the railways in 1901, the majority of registered prostitutes identified as Estonian (60%), followed by ethnic Russians (14%) and Latvians (13%)[11]. By 1906, just 38% of Tallinn’s registered prostitutes were Estonian, 27% were Latvian and 17% Russian[12]. Polish, German, Lithuanian, Finnish and Jewish women made up the remainder of the lists.

The history of prostitution and venereal diseases in pre-independence Estonia enhances wider social and urban histories of the region, as well as illuminating histories of migration and imperialism. Official explanations of Tallinn’s high rates of venereal infection were often suffused with the ethnic prejudices of the Russian imperial state. Representatives from Estliand province’s Medical Department used rates of infection as evidence for the apparent cultural and social inferiority of the non-Russian local population. The Department purported that due to the epidemic levels of syphilis across the province, the indigenous population was ‘on the way to degeneration’ and that there were hundreds of ‘epileptics and idiots suffering from various deformities’ across the region[13]. An Empire-wide survey of registered prostitutes claimed that registered women in Estliand province were almost twice as likely to have a venereal disease than their counterparts in other European Russian provinces.[14]

These explanations of why Tallinn and the surrounding Estliand province had such high levels of venereal infection cannot be taken at face value. There was no uniform method of collecting statistics on venereal diseases in the late Russian Empire, and data are often patchy at best. In the early 1900s, physicians did not have any reliable diagnostic procedures or cures at their disposal to accurately detect and treat venereal diseases. The Empire’s largest cities had the amplest treatment facilities, yet even in St Petersburg and Moscow, hospitals often did not have enough beds or medicine to adequately treat the urban population. Additionally, the budgets of municipal authorities did not stretch far enough to ensure the regular effective inspection and treatment of registered prostitutes. Examinations were often rushed due to staff shortages, and even talented physicians were unable to accurately detect venereal infections within the meagre few minutes they were allotted per woman.

As well as poor medical facilities, municipal authorities did not make the policing of prostitution a financial priority. The Russian Empire’s police force was chronically understaffed, numbering just 47,866 men for a population of 127 million at the turn of the twentieth century[15]. Policemen’s wages were pitiful, which encouraged many to take bribes from registered prostitutes and brothel madams hoping to bend the rules of regulation. Certain members of urban communities claimed that police corruption helped to facilitate the circulation of venereal infection.

In March 1907, one Tallinn resident wrote to the authorities to complain about this very problem. Earlier that year, Peter Grenbaum had denounced Akulina Vakher as a clandestine prostitute after she allegedly infected him with a venereal disease[16]. However, Grenbaum claimed Vakher was now paying regular bribes to the local police to avoid having to register as a prostitute and attend biweekly examinations. In another case, the Maritime Ministry Commander of Tallinn’s port wrote to the Estliand Governor to complain about the lack of police supervision over city taverns. According to the Commander, various low-ranking sailors caught venereal diseases after having sex with barmaids at Tallinn’s Lavla Inn, yet the police did nothing to rectify this ‘disgraceful situation’[17]. We cannot assess the validity of these statements due to fragmented source material, so it is difficult to uncover whether the accusations were based on genuine concerns or personal grudges. However, ample evidence from various towns across the Empire reveals that corruption was an integral part of the regulation system, and that many women paid the police to ensure as little interference into their lives as possible.

The geographical position of the Baltic provinces was also used as an explanation for high rates of venereal infection in Tallinn and the surrounding province. The Baltic region had good railway connections to central and eastern Russia, as well as Western Europe. By the early 1900s, the Baltic provinces were a key exit point for emigrants leaving the Russian Empire in search of a better life overseas. Estliand province’s coastline was also home to several major resorts, and as the area was well connected to the capital by rail and steamship, tourists flocked there during the summer months. While temporarily away from home or in transit, people allegedly behaved differently, engaging in promiscuous and commercial sex, and facilitating the spread of venereal infection.

Reportedly high rates of infection in Tallinn could have actually been a result of the poorer available medical facilities and limited police presence outside major urban centres, or the region’s reputation as a magnet for tourists and holidaymakers. Despite this, some contemporary educated observers ignored these factors and used such figures to reinforce stereotypes about the supposed cultural backwardness and ‘deviance’ of the empire’s non-Russian, non-Orthodox populations.

[1]Rasprostranenie i Bor’ba s Polovymi Bolezniami, Glavnym Obrazom v Revele’, Russkii Zhurnal Kozhnikh i Venericheskikh Boleznei (RZhKVB) 9-10 (September 1913), pp. 273-274.

[2]I. I. Truzhemeskii, ‘Nekotorye Dannye o Rasprostranenii Venericheskikh Boleznei v Revele’, RZhKVB, 4 (April 1914), pp. 395-396.

[3]Tsentralnyi Gosudarstvennyi Istoricheskii Akhiv Sankt-Peterburga (TsGIASPb), f. 569, op. 18, d. 4, l. 33. In the capital, prostitutes were forbidden from living in various central locations, such as Nevskii, Liteinyi, Vladimirskii, Voznesenskii and Izmailovskii prospekti, and the entire first and second parts of the Admiralteiskii district. TsGIASPb, f. 593, op. 1, d. 601, l. 11.

[4]Glavnoe Upravlenie po Delam Mestnogo Khoziaistva, Vrachebnoi-Politseiskii Nadzor za Gorodskoi Prostitutsiei (St Petersburg, 1910), p. 26.

[5]Vrachebnoi-Politseiskii Nadzor, p. 61.

[6]EAA.31.2.6909, lk. 2.

[7]Jaan Tamm (ed). Entsüklopeedia Tallinn 1. A-M (Tallinn, 2004), pp. 195-196. With thanks to Teele Saar of the Estonian Maritime Museum for sharing her Tallinn expertise and providing me with the reference.

[8]EAA.31.2.4509

[9]Toivo U. Raun, Estonia and the Estonians, 2nd edn. (Stanford, 2001), p. 71.

[10]John Westwood, A History of the Russian Railways (London, 1964), p. 76.

[11]EAA, 31.2.3722.

[12]EAA, 31.2.4681.

[13]EAA, 30.6.3628 lk. 2-4.

[14]Vrachebno-Politseiskii Nadzor, pp. 10-11, 26-27.

[15]Neil Weissman, ‘Police in Tsarist Russia, 1900-1914’, Russian Review, 44, 1 (1985), p. 47.

[16]EAA, 330.1.1651, lk. 130.

[17]EAA, 31.2.3274, lk. 50.

Dr. Siobhán Hearne is a postdoctoral researcher currently based at the University of Latvia in Riga. She received her PhD from the University of Nottingham in 2017 for a thesis on the regulation of female prostitution in the Russian Empire, 1900-1917. She has published several articles on gender and sexuality in late imperial Russia and the early Soviet Union.

© Deep Baltic 2018. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.