by Pauls Bankovskis

“And the waters decreased continually until the tenth month: in the tenth month, on the first day of the month, were the tops of the mountains seen.” – The First Book of Moses

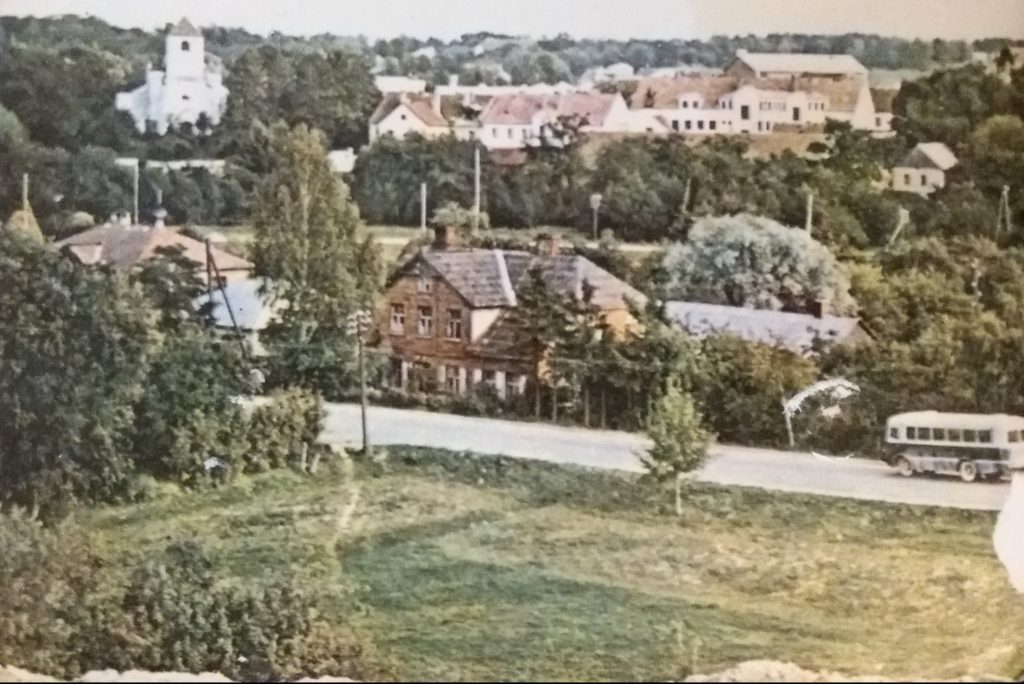

I discovered masturbation at almost the same time that I discovered the map of Latvia. My father had found the map in the attic of the old office of the Lauktehnika kolkhoz in Sigulda, where – probably because it no longer corresponded to Soviet reality – it had been hidden at the very dawn of the founding of the kolkhoz. In my imagination, Pytalovo had already become a place that was in some way special, because it was to there that an incredibly short train crawled once a day along the nearby railway line, always pulled by a black steam engine. And yet on the map that was hung above my bed, this town was labelled as Abrene1, and even to me it was clear that some dangerous contradiction was hiding there. And then, of course, the many narrow-gauge railway lines in different parts of Latvia – these were marked on the map, but in reality they no longer existed. The rails for the Līgatne paper factory’s little steam train had been torn up too.

Formally, I was born in Cēsis (to which we will return a little later), but I have always considered myself to come from Līgatne – and it was probably under the influence of that childhood memory that I later became a big fan of narrow-gauge railways. The map had been issued in the 1930s by Pēteris Mantnieks map publishers; they had created it on a rough linen base, with separate square printed sheets carefully glued together. Here and there, at the places where it had been glued, the paper had come loose, and at some of the edges and corners of the sheets it had become ragged, uncovering the fabric underneath and adding to the map new shapes, non-existent on the topography of Latvia, which I had once tried to colour in with felt-tipped pens.

The top and bottom edges of the map were set in heavy, black-painted wooden laths, which over time from their own weight and the weight of the map had become bent inwards. Although some half a century had passed since the map’s printing, its colours were still brilliant – much brighter than those maps, always in dull, pale colours, which the former Mantnieks map publishers, then called simply “Printing Works No. 5”, printed during the Soviet years. My father had worked at that printing works at some point before I was born, and that was the only reason I knew about its existence – as, just like anything with the slightest military significance, the site was considered secret.

The valleys and ravines on my map were a lush shade of green, and the deeper they were, the darker and more intense the greenness. For their part, the hills and hillocks, tracing the bends of the isopleths, only little by little rose from light yellow up towards orange-ochre peaks. To an observer who didn’t know the geography of Latvia well, who had not bothered to take a look at the key to colour and heights included in the map’s legend, the sharp contrasts might have created the misleading impression that this was not just “little Switzerland”2, but that all around mighty Gaiziņkalns stretched a land of real mountains and of gorges worn by rapid rivers. It could even be that these thickened colours indirectly reflected the efforts, so popular under the Ulmanis regime3, to view Latvia in absolutely all domains as, if not other countries’ superior, then at least of equal worth.

This kind of map was really a completely innocent undertaking compared to the portraits of old Latvian kings, artists’ fantasies, that were hung on the walls of the presidential palace in an attempt to justify the illegal seizure of power. But, of course, at that time I still hadn’t heard of those kings, although both Ulmanis and the Ulmanis times were mentioned in the adults’ conversations at almost every get-together. From these conversations I perceived that some things were better at that time than they were now, but that for some reason it was better not to talk about this outside the house. To put it in a few words, at that time I already had an inkling that the world was filled with incomprehensible contradictions and dark secrets.

The light in my room had already been turned off, but sleep still would not come, and I gazed slantwise across the room to right where the map was hung on the wall; in the half-light it looked black and white. In the next room, my parents were watching television. It was on one of those evenings that I found out for the first time about the phenomenon which is now of course known as global warming.

In the television broadcast, it was reported that above the poles, holes in the ozone layer were forming, and that more and more of the sun’s rays were getting in through these holes in the atmosphere. These rays were melting the blanket of snow that covered the Earth’s poles, and so the water in the seas and oceans was rapidly rising. By the time all the icecaps had melted, the water level everywhere in the world would have risen by approximately 80 metres.

I had got to know this map of mine rather well, and I myself was able to grasp that we would escape by a mere hair’s breadth. We had moved from Līgatne to Sigulda when I was four, and on the map you could clearly see that Sigulda, at the edge of the Gauja valley, was just a little higher than 80 metres above the current sea level. Of course, after the melting of the icecaps, the valley would – as my parents would put it – be full to the lip, and the Vējupīte stream would be just as full, bursting its banks so that it would be almost lapping against our own house, and flooding the meadows on the other side.

And you could totally forget about Riga – it would be turned into a little Atlantis. Below the waters also would disappear entirely the lowlands of Zemgale, and many other places.

But although I should have felt safe (for the moment at least), I couldn’t manage to get to sleep with all these thoughts in my head, and I probably would not have managed to do so the following evening either, or the one after that – and it may even have gone on like that until the icecaps had completely melted. But it was around this time that I discovered “self-pacification” – as it then used to be referred to in articles. And it has to be said, this term was rather apt, because at that time this newly acquired hobby had little to do with sexual fantasies; it was more the second part of the word that was essential – namely, recovering lost peace, and the sleep that soon followed.

Something else made me a little uneasy, because I had either read somewhere or heard at school that onanism – a term that already sounded suspiciously like a dangerous illness – could seriously imperil both the flesh and the spirit, and so we should shun and abstain from it with all our strength.

As the icecaps melted, below the waters would also descend the little settlement built for the paper factory workers in Lower Līgatne where the first years of my life had been passed – though, as I’ve already mentioned, I was born in Cēsis4, and Cēsis is in a place of still more peace and safety. Almost every visitor to the town is informed that the stone doorway of Cēsis church is exactly a hundred metres above sea level, or the very same height as the golden cockerel atop St. Peter’s Church in Riga (meaning that in the great flood at least the cockerel would remain above the water level, although I don’t think this would be a great consolation to the majority of Rigans).

But there was no maternity department at the little hospital in Līgatne, and so one March morning, realising that she was about to give birth, my mother put on a coat, probably tied a scarf around her (at that time women of reproductive age of European origin also tended to wear headscarves), and got into the little UAZ-made ambulance bus that had arrived from Cēsis.

About what had to be done at that moment and how, she definitely already had knowledge: my brother and two sisters were born before me – the oldest of them twenty years earlier.

As it was a Saturday, my father would most likely have been at home, but he still didn’t go along with her – that simply would not have been accepted. Or maybe he wasn’t at home at all, but together with his partner Augusts from the painters’ brigade had gone to do some work illegally renovating the kolkhoz dairy.

The territory of Latvia has more than once been overtaken by ice cover. During the Ice Age, while the climate was cooling, the icecaps expanded, but as it became warmer, they retreated back northwards, and in this way it happened four times. All this movement, fermentation, freezing and thawing had already started to reshape the surface of the land under the dormant ice, but the biggest changes of all were brought by the great melting of ice that took place at the close of the Ice Age. So much water suddenly welled up that there was nowhere for it to go, and the waters flowed and flooded over everything, gnawing and tearing new cracks and passages in the ice. But in those places where the ice had already melted, the waters pulled stones, sand, earth and clay along with them with enormous force, and these left behind deep ravines. One of those ravines was the Gauja Valley.

The little UAZ bus crawled, puffing, along the zig-zag road which flowed alongside the narrow-gauge railway tracks, up from the valley threatened with inundation, turned towards Cēsis, and before a full hour had passed, my mum had been allotted a place on a five-person ward at the old hospital on Komjaunatnes iela5. Her waters had broken, and I was born at midday that very day, a few moments after twelve. I was weighed and measured, a slip of oilcloth with a number on it was tied around my leg on a little string, and then I was put together with the other babies in the babies’ ward. The newborns were allowed to be with their mothers only at feeding times.

After a few days, we drove back down to Līgatne, and they started to bring me up according to all the latest directions from Benjamin Spock. No one was yet bothering themselves over holes in the ozone layer, and the ice caps for the time being had still not melted, but one day, awakening in my cot, I suddenly had the feeling that I had been abandoned, left all by myself, and that over me, along a narrow and dark ravine, something unstoppable, huge, black and heavy was rolling. For the first time, I felt a growing unease, but until my first map and the great discoveries it brought with it, I would have to remain patient.

1. Abrene [before 1938 officially known as Jaunlatgale] is a town that was part of the Republic of Latvia during the interwar period. In 1945, following the occupation of Latvia by the Soviet Union, Abrene and its surrounding district was transferred from the Latvian SSR to the Russian SSR and the town was renamed Pytalovo. Following the break-up of the Soviet Union, it remained part of Russia.

2. Sigulda and Līgatne are both in the picturesque and moderately hilly Gauja region of northern Latvia, which is popular with tourists, and has been promoted as “Little Switzerland” or “the Livonian Switzerland” for more than a century. Latvia is on the whole a very flat country, with its highest peak, Gaiziņkalns, only slightly over 1,000 feet.

3. Kārlis Ulmanis seized power in a bloodless coup in 1934, and, suspending parliament, instituted an authoritarian government, which lasted until the occupation of Latvia by the Soviet Union in 1940.

4. Cēsis is a larger town in the Gauja valley, around twelve miles from Līgatne.

5. Komjaunatnes iela translates as “Young Communist League Street”.

This piece originally appeared in the “book-magazine” Plūdi (“Flood”) published by Satori. Translated from Latvian by Will Mawhood.

Pauls Bankovskis’ novel 18 was published in English earlier this year, and is available from Vagabond Voices publishers.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.