Jonas Mekas is a legend. Even those who do not know about him, but are aware of the New York scene in the ’60s and ’70s or know about Lithuania have heard the name of Jonas Mekas. Yet his artistic oeuvre is elusive, and it is a rare person who can name a work by Mekas. His film-making is experimental, short in length, poetic, personal, and quite the opposite of the narrative movies which are most often associated with the idea of cinema. Jonas Mekas was a famously sharp-eyed – and also sharp-tongued – film critic and, permeating all, a poet.

Mekas the film-maker

Jonas Mekas’s cinematic work is a jumble of film, with emphasis on the visual poetry of the captured moment as much as the sound. His camera participates, questions, intertwines, untangles, cuts, explores, turns on itself, dances and most importantly archives; it sketches out the face of an entire generation, as varied as Andy Warhol, who became the central figure of the New York pop-art movement; the first lady, Jackie Kennedy; the pioneering performance artist Yoko Ono; the filmmaker Carl Theodor Dreyer, of whom Jonas Mekas made a film portrait in 1965; and the surrealist painter and filmmaker Salvador Dalí, who came from Spain especially because he felt “something seemed to be happening in New York,” and Dalí wanted to be part of it. Together in 1963-64 they made a series of happenings, which Mekas made into a short film called Salvador Dalí at Work. Mekas also made a silent film with Andy Warhol called Empire.

Revisiting rolls of footage, Mekas later made films about many of the people and places that had been a part of his earlier life. This Side of Paradise, which is about the summers that Mekas spent with the Kennedy family, was completed in 1999.

However, Mekas had been highly regarded as a filmmaker as early as 1964, when Jonas Mekas and Adolfas Mekas received the Grand Prix for best documentary of the Venice Film Festival for The Brig, a filmed stage play that has been called ‘a modern inferno’, written by Kenneth H. Brown as a production for the avant-garde Living Theater in NYC.

Mekas the film critic

Beginning in 1958, Mekas published a regular film diary in The Village Voice, and was able to earn money with his intellectual work – although not with his camera, but with words. In 1972, Jonas Mekas selected the most important of his writings and published them in a book called Movie Journal: The Rise of a New American Cinema, 1959-1971; it contains about a third of his Village Voice articles, and was reissued by Columbia University Press in 2016. “The book is a rich trove of cinematic wisdom, an artistic time capsule of New York at a moment of crucial energy, and a reflection of controversies and struggles regarding independent film-making that endure to this day,” Richard Brody wrote in his 21st April, 2016 review in The New Yorker.

In 1954, to express his eager mind, Jonas Mekas had co-founded a publication called Film Culture, but his most extensive work belongs to The Village Voice, where Mekas worked until 1977. More than 60 interviews, along with still shots from his films, have been re-published by Spector Books under the title Conversations with Filmmakers. The publication includes interviews with Jerome Hill, Vittorio De Seta, Gregory Markopoulos, Storm De Hirsch, George and Mike Kuchar, Mike Getz, Andy Warhol, Nico Papatakis, Taylor Mead, Claes Oldenburg, Shirley Clarke, Albert and David Maysles, Tony Conrad, Peter Kubelka, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Ken Jacobs, Susan Sontag, John Cassavetes, Michael Snow, Kenneth Anger, Anna Karina, Hollis Frampton, Yvonne Rainer and Carolee Schneemann, and many other avant-garde artists and filmmakers. “Each interview is a record of the artistic vision of the late 20th century and also a wonderful scrapbook and visual document of artists,” notes its editor Anne König.

In order to gain access to independent movies Mekas had co-founded the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, which began regular screenings at the Film-Makers Cinematheque. In 1969, Mekas contributed to setting up The Anthology Film Archives, which remains the largest and most important archive of experimental cinema. Filmmakers Jim Jarmusch and Martin Scorsese are among those who have cited Jonas Mekas as a key influence.

Mekas’s poetry and music

Mekas’s name also rings in the ears when we hear of musicians and bands such as The Velvet Underground and Nico, Patti Smith, Lou Reed, Sonic Youth, and Beatles singer and songwriter John Lennon during his New York years…. In May 1969 John Lennon and Yoko Ono held their famous Bed-In for Peace event and it was Jonas Mekas who filmed it. Mekas made the very first recording of the Velvet Underground, which was nothing more spectacular at that time than a recording of a blasting fun Uptown party. Today, however, this video, along with many of the other videos, has become legendary. It is a recording of a spirit of time.

Mekas is often referred to as the godfather of American avant-garde and independent cinema, one who dared to use the language of cinema to turn the ordinary into visual poetry. He lived in a whirl of experimental musicians and poets such as John Cage and Allen Ginsberg, and the mastermind of the highly influential international cooperative Fluxus (established 1960), George Maciunas, with whom Mekas shares Lithuanian origins.

However, as a sharp and often condemning critic, Mekas wrote in English, criticising commercial cinema, condemning censorship and the poverty of avant-garde artists. Through his enthusiastic criticism Mekas sought to bring a personal dimension into how the work of liberated artists and filmmakers is regarded. However, Jonas Mekas was first and foremost a poet and in his lifetime, he published numerous volumes of poetry. Mekas’s poetic expression is also the underlying soundtrack of his films. Much of his written poetry was in Lithuanian. It is when Mekas makes his art, not writes about cinema, that a softer language emerges, and it is often Lithuanian. Mekas remained fluent in Lithuanian all his life, and often expressed himself on stage by singing traditional Lithuanian folk songs.

Mekas and Lithuania

Mekas always emphasised his Lithuanian origins and was keen to tell his story of war, displacement and immigrant life at the bustling heart of the American avant-garde. A sickly child in the Lithuanian countryside, Jonas had spent a lot of time reading. His writing career commenced during his teenage years in Lithuania, when he wrote essays and poetry, publishing them in an underground journal. It was also in Lithuania that Mekas began taking photographs, but his camera was confiscated by soldiers during the war before he saw the results.

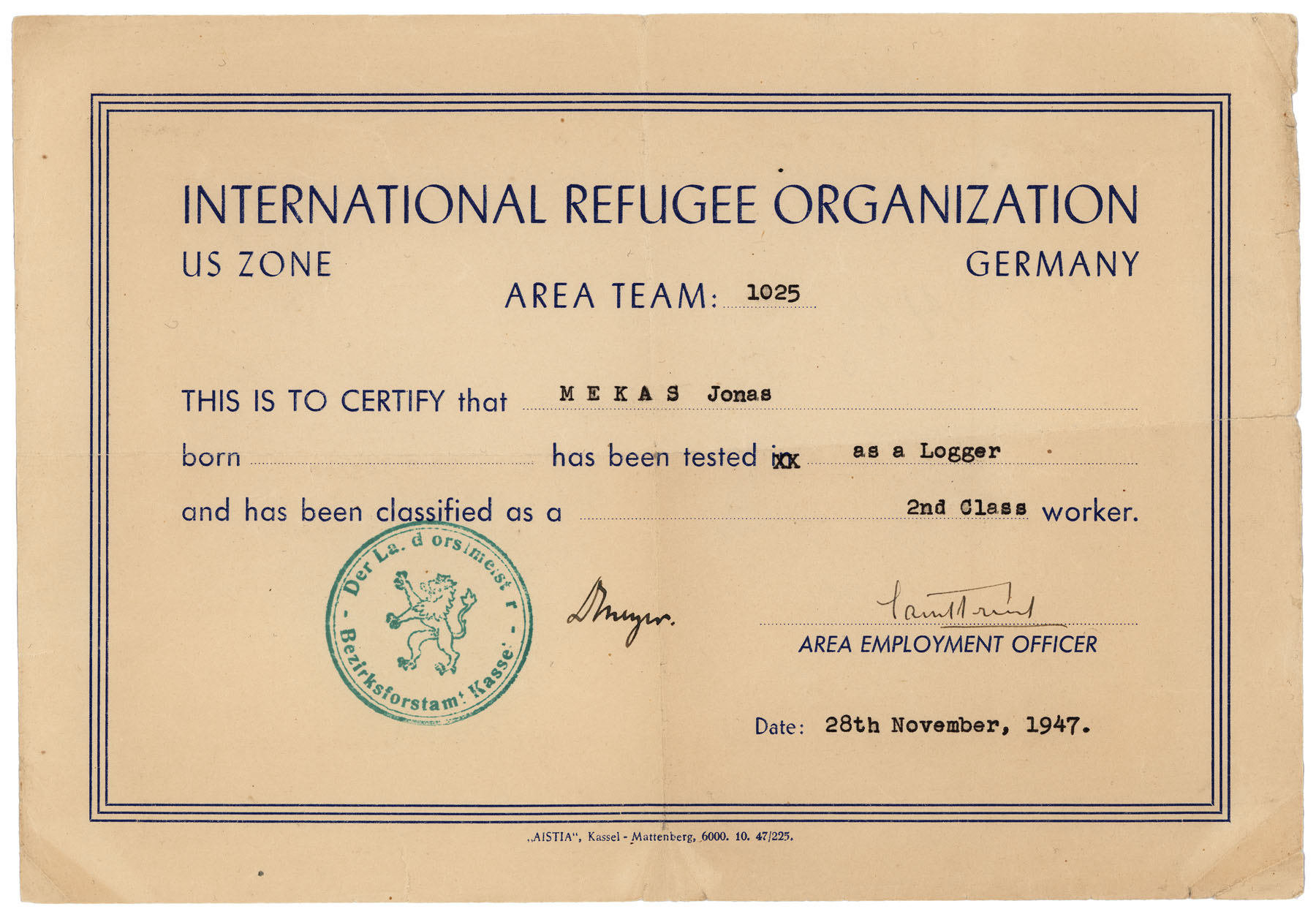

In the late 1940s he fled Lithuania together with his brother Adolfas, and both were arrested and sent to a Nazi labor camp. Later the brothers spent aimless years in hiding and in displaced persons camps, where Mekas spent his days idly watching commercial movies, all the while keenly absorbing the life around them.

Along with his portrayal of the avant-garde, Lithuania and his years of displacement became the central themes of Mekas’s work and he returned to them repeatedly. Living in between English and Lithuanian, the cinema became his universal language of expression. Jonas Mekas is best known for his personal cinematic diary, the most famous films being Walden (Diaries, Notes, Sketches) (1969), Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1971), and As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (2000); the first two of them are largely about Lithuania.

In 2016 Jonas Mekas, represented by the James Fuentes Gallery in New York, had a solo show at the most famous commercial art fair in the world, ArtBasel.

In contrast to the sleek booths that surrounded him, Mekas’s show at Fuentes presented a series of photographs from a D.P. Camp, Kassel/Mattenberg, where Jonas and his brother had spent four years. Mekas’s film Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1971) was part of the prestigious film programme.

Jonas Mekas photographed in 1945: “With my new friends just after arriving in Wiesbaden D.P. Camp” [Image used with permission of James Fuentes, New York]

I had corresponded with Jonas Mekas irregularly by email since 2013, and we arranged to finally meet during the fair at the Fuentes booth.

In Memoriam Jonas Mekas

Jonas Mekas died at the age of 96 in the evening of January 23, 2019. His Facebook page announced: “Jonas passed away quietly and peacefully early this morning. He was at home with his family. He will be greatly missed but his light shines on.” And indeed, Mekas light shines on and his presence can most definitely be traced to avant-garde, video art and independent film artists around the world.

In 2013, on the occasion of his 90th birthday, Jonas Mekas had a slew of shows and interviews around the world, celebrating his place in art and film history, including a survey at the Serpentine Galleries, side by side his major retrospective at the BSI in London, Pompidou Centre in Paris, Tokyo etc. Some months prior to the opening, the U.K. daily The Observer published a Jonas Mekas exhibition preview, which cited the maverick film-maker Harmony Korine famously summing up the singular spirit of Mekas: “Jonas is a true hero of the underground and a radical of the first degree – a shape-shifter and time-fucker… he sees things that others can’t… his cinema is a cinema of memory and soul and air and fire. There is no one else like him. His films will live forever.”

Jonas Mekas has certainly claimed his place in the history of cinema. However, his work seems to transcend genres, and in its entirety Jonas Mekas’s oeuvre can be viewed as an extensive study in shaping, revisiting and poeticising memory, both individual and collective. His great friend the fashion designer Agnès B, has memorably described him as “an artist, a scribe and a keeper of memories”.

In essence, Jonas Mekas was a part of all of the personalities and artists he worked alongside – he carried them in his work as much as they carried him in their art. Jonas Mekas participated in his own time and in his own documenting of it. As for the generations that came afterwards, what he has left for us in this age of technology and abundance of home-made videos, is the reminder of the beauty of life on a human scale.

Zané Elksnite Grants-Wolff is an art advisor and curator. She is of a younger generation than Mekas, but quite similarly her family left their home in Latvia during the Cold War; they watched the fall of the Berlin Wall from a displaced persons camp in Austria. In United States, she was one of the first to receive a degree in Baltic Area Studies from the University of Washington in Seattle, the only university in the U.S. where the languages and culture of all three Baltic countries are taught. In addition to majoring in English with emphasis on writing, she enthusiastically studied cinema and art history, becoming friends with many local artists and writers of her generation. Zané returned to Latvia on a Fulbright scholarship and later moved to Lithuania, where she lived for more than ten years prior to moving to Switzerland. Since 2013 she has been personally in touch with Jonas Mekas, exchanging letters and discussing work projects. They met during Art Basel in 2016.

© Deep Baltic 2019. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.