by Will Mawhood, RIGA

Riga is the largest capital city in the European Union not to have an underground rapid transit system. Doesn’t sound like much of a hook, does it?

Europe’s busiest and most extensive metro – that would definitely be worth a read. That’s Moscow, incidentally – the core of its network constructed under Stalin’s reign and made up of famously opulent and formally adventurous stations. There would be plenty of stories to tell about the oldest metro system in Europe (and indeed the world) – that’s the London Underground, operational since 1863. Even the tale of the smallest metro system to be found on the continent might make for a diverting, if insubstantial piece – and that, by the way, is in Lausanne in Switzerland, a city which has just a little under 150,000 residents but which still qualifies for a largely underground system with 29 stations.

Riga isn’t even the European capital that has been waiting the longest time for a metro system – that’s metro-less Belgrade, where a rapid transit system was first mooted in the 1930s; construction was delayed first by the destruction to the city caused by World War II, and then by a series of other mishaps and disputes over finances, not to mention the wars and severe political instability that Yugoslavia experienced in the ‘90s. Despite a succession of declarations of intent (most recently, that ground would be broken by the end of 2018 – which didn’t happen1), almost nothing concrete has been achieved beyond two underground stations linked to the main railway network. So long and so apparently interminable has the wait been that locals apparently make jokes about “waiting for metro”, a wry allusion to Waiting for Godot.

Compared to all of this, an exploration of what is in essence just a notable absence might seem a little lacking in drama and colour. But the story of why Latvia’s capital doesn’t have a metro is very definitely interesting – I promise. Because the city was down for a metro – a three-line network, in fact, a formally and conceptually adventurous system that would have been the most expensive ever built in the Soviet Union, and which would have extended to every corner of the city and then snaked out beyond. First envisioned in the early ‘70s, it had a lengthy gestation period with many setbacks and delays, but when it finally seemed ready to go in the late ‘80s, everything fell apart as it came up against suddenly emboldened movements for autonomy and environmental protection. After a ferocious campaign of opposition from local residents and pressure groups conducted under the slogan “Metro Nav Draugs” (“The Metro Is Not a Friend”), the idea was quietly dropped.

So why was Riga awarded a metro system, and why did it so vehemently reject it?

Well, it’s a knotty one, and almost every one of the issues that have troubled and torn this country in recent decades are snagged upon it. But to tell this story properly we need to jump back to the Riga of the 1960s, where the scheme to build a metro system has its roots. And the capital of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic was in all kinds of ways a very different place to the city of today – in fact, there can be few cities in Europe that have changed quite so much in the last half-century.

For one thing, it was a city growing at breakneck pace: in 1965, Riga’s population was around 650,000 – more than double what it had been immediately before World War II, when it was the capital of the independent Republic of Latvia. Forcibly annexed by the Soviets in 1940 after rigged elections conducted under military supervision, the country had subsequently seen a three-year occupation by Nazi Germany, before the return of the Soviets in 1944. During the years that followed, the Soviet authorities consolidated their power by gradually eliminating a substantial partisan movement active in the forests, while the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic saw intense industrialisation and collectivisation of agriculture.

The population growth was largely driven by these new factories – although in some cases, instead of starting from scratch the Soviets simply expanded industries that had existed before the war. This was the case with VEF in Riga, founded in 1919, the first year of the independent state, which became the flagship company of the Latvian SSR and one of the largest electronic concerns in the Soviet Union.

Every other telephone produced in the USSR was made at VEF. It was also the reason why most Soviet radios had Latvian names – including the very first Soviet-made transistor radio, the popular Spīdola model, bought from Uzhhorod to Sakhalin, whose production continued until 1991. The factory even developed the first Soviet bobsleigh in the early ‘80s, after Leonid Brezhnev expressed displeasure at the USSR being outpaced at the 1980 Winter Olympics by East Germany. (Latvian bobsleighers thereafter won a number of Olympic medals for the Soviet Union, and Latvia continues to be a world force in bobsleigh and skeleton racing). VEF exemplified the perception of Latvia held in other Soviet republics: dynamic, creative, advanced.

Riga was also, by Soviet standards, extremely prosperous – along with its Baltic neighbours Lithuania and (especially) Estonia, Latvia had the highest standard of living and the highest wages in the Soviet Union. The combination of high demand and high rewards drew workers from across the Soviet Union.

But Riga’s appeal was about more than just money – the city was also a window onto a past that most of the Soviet Union had never had, and which could, in the right light, be mistaken for the kind of places that most would never be able to visit. A West-facing port founded by German crusaders, and which had spent almost a century under the rule of the Swedish Empire, Riga was visually European in a way that few other places in the country were, and was consequently a draw for tourists from the east. The narrow, rambling streets of the Old Town and the imposing boulevards beyond often stood in for Paris and other Western European cities in Soviet films – indeed, the Soviet take on Sherlock Holmes, played by Vasily Livanov, made his home at Jauniela in Riga Old Town.

But industrialisation and migration brought complex consequences in their train – not only did Riga’s population almost double, but the city’s ethnic make-up also flipped: Latvian-speakers had been 63% of the population before the war, but by the end of the ‘50s they were in a minority, outnumbered by Russophones (a topic we will come back to). Its ballooning population meant that Riga was affected especially badly by the acute post-war housing crisis. The solution decreed by Stalin’s successor, Nikita Krushchev, was large-scale construction of cheap blocks of flats – the long, low-rise, slotted-together rectangles, grey and featureless, that became known as khrushchyovkas and continue to exemplify Communist housing in the Western imagination.

The first sizeable concentrations of khrushchyovkas in Riga were put up in the late ‘50s in the districts of Āgenskalns and Iļģuciems – both in Pārdaugava, as the parts of Riga on the far side of the River Daugava are collectively known. Pārdaugava would become host to further sprawling developments in the following decades further out, in Imanta, Ziepniekkalns and Zolitūde. This significantly increased the number of people living on the other side of the river, historically a fairly low-density and exclusive part of the city, where Riga’s moneyed classes had once fled to escape the soot and chaos of the city centre.

But most jobs remained concentrated on the right bank of the Daugava, in the city centre and the cluster of factories just beyond – the VEF factory among them. Today within Riga’s city limits there are four road bridges over the River Daugava, but in the ‘60s there was only one, which was increasingly placed under strain – all the more so at peak times when people were coming to and from work. And once road traffic had reached the right bank, it was hemmed in – by the narrow, winding streets of the Old Town on one side, and a cluster of looping railway tracks on the other. The result, unsurprisingly, was gridlock. And with Riga’s rapidly increasing population, it could only be assumed that the number of people and vehicles flowing over the bridge at rush hour would also rapidly increase.

Aware of how overstretched and outdated Riga’s infrastructure had become, throughout the 1960s the authorities made various attempts to find a catch-all solution to the city’s transport woes. One idea was a high-speed tramline – which would have been the first in the Soviet Union and among the first in the world – that would dip below the ground for a brief stretch in the city’s densely populated heart; another was extending and branching out Riga’s commuter railway network beyond the small number of stations already existing close to the city centre. But neither was felt to adequately resolve the problems that had developed – either services would be too infrequent, or the impact on the principal commuter flows would be too limited.

There seemed to only be one other alternative standing between Riga and gridlock – a metro system. And in 1976, orders were given for technical and economic planning to begin for the construction of an underground rapid-transit system in Riga.

And metros, for the Soviet Union, were not simply another form of transport. Metros were something that, by common consent, it did very well. The country prided itself on the bold and ambitious systems it constructed, and Soviet experts travelled the world to work and advise on other countries’ underground systems.

Even after several decades during which the attitude taken towards Soviet architecture has very often been one of contempt, its towers and residential housing derided as production-line and depressing, its war memorials and public monuments superhuman and bombastic, and its public spaces deliberately intimidating, vast gulfs, its metro systems have escaped unscathed. Awestruck coverage still regularly appears in travel and cultural sections about the palatial stations of the Moscow metro – a project that could certainly be described as bombastic and intimidating in scale, not to mention having been initiated under a tyrant and completed at the cost of considerable human suffering.

To try to work out just what it was that the Soviets got right about metro systems, I spoke to Owen Hatherley, author of Landscapes of Communism, an overview of the architecture of the Soviet Union and postwar Eastern Bloc. The book includes a whole chapter dedicated to the metro systems, which Hatherley describes as “the one area where I genuinely do believe that the practice of the Soviet Union was vastly superior to that of the West”. I asked him why he thought they had escaped the condemnation heaped on so many of the regime’s other architectural endeavours.

“One of the things with all of those metro systems is that they’re the least claustrophobic underground spaces on earth – and that I think is really, really crucial. Although you’re underground, you’re in something that’s spacious and light and ethereal – rather than feeling that you’re in a tunnel under some mud, which is what you are… The dimensions of a street when they’re blown out into massive Stalinist proportions become very dominating and intimidating, because people relate quite intimately to their urban space, and being placed basically in an architectural model is a little bit unnerving and uncanny. But the same approach in a metro is actually quite reassuring and relaxing.”

What’s more, he points out that it’s a mode of construction for which the Soviet economy was actually rather better adapted than its Western competitors: “this was a totally controlled environment, right down to the air that was pumped into it. Whereas the street above – even though you didn’t have to deal with private interests – you had to deal with the existing city, particularly after 19562 you had to deal with public opinion; there were various ways that you couldn’t completely do what you wanted. Whereas you could treat a metro like a command economy – all metros are built like a command economy – that’s how you build metros. Pretty much the only exceptions are the British ones of the very early 20th century, but that aside metros are state planning. And for a regime that was committed to central planning and the command economy on that scale, it was an obvious match, in the way that the ideology and the engineering capability and the general approach all met.”

He went on to say “and also, the thing that comes with it being a controlled environment is that it was treated as a propaganda environment… it was treated as a place that was supposed to work almost as an educative thing – you know, they would tell stories and it would work as a showcase environment. I think that’s really important. Obviously the Soviet regime was full of showcases – exhibitions of economic achievement, Stalinist grand buildings, and so forth, but this one was just much more effective, for one reason or another”.

Metro systems were seen as an asset, that was for sure – and great Soviet cities had to have one. It was a legal requirement that any city of over a million people had to have a metro system underway. Some smaller cities went to extraordinary lengths to ensure they got the nod – Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, then also a Soviet republic, began a push for a metro of its own in the late 1960s, when it had a population of only around three-quarters of the necessary figures. It’s alleged that in an attempt to win over an apparently sceptical bureaucracy, the Armenian Communist Party organised nightmarish traffic jams to greet the visiting officials from Moscow, hoping to create the impression of a city utterly paralysed as a result of its inadequate public transport. Karen Demirchyan, then the leader of the Armenian Communist Party, used further imagination in his public appeal, claiming that due to the growth and development of the republic, the famously large Armenian diaspora (still larger than the total population living in Armenia) would soon be tempted home, meaning that the population of Yerevan would more than double by the millennium.

Riga was in a similar position to Yerevan. For, despite its rapid growth, the city had not topped a million, and could not be expected to do so for at least a decade (in fact, it never would – the city’s population peaked at over 900,000 in 1989, just before Latvia restored the independence that had been forcibly taken from it). Certainly, there were many Soviet cities larger.

It’s notable, though, that Riga did not have to go to any such lengths in trying to convince Moscow of its case. And this likely has something to do with the certain symbolic importance Riga had – what it represented was more significant than mere size. It was, within the somewhat warped conditions of the Soviet Union, a boom town. More than that; as Ija Niedole – who went on to serve as the lead engineer on the project from Pilsētprojekts, the republic’s construction institute – noted when interviewed in 2015, “the attitude towards Latvia within the Soviet Union was good (Riga was even considered to be a model)”.3

If the metro was a showcase for all that the Soviet system could achieve, Riga itself was something similar: a city both dynamic and historic, a city that might be able to absolve the Soviet Union of the charges levelled against it. Riga would jump the queue.

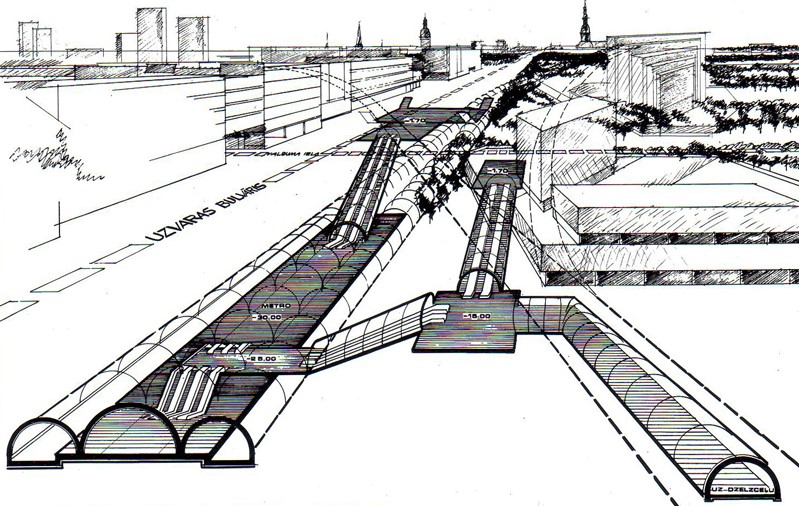

The project was assigned to the Moscow-based institute Megiprotrans, and, in 1977, the first set of preliminary plans for the Riga metro were unveiled. Megiprotrans had drawn up an extensive two-line route, laying an X underneath the city, west to east, north to south. It was projected to be an extremely busy system, with up to 40 trains an hour at peak time, and the expectation was that work would be complete on the first line by 1990.

But the following year came and went, as did several more years after that, and still no ground was dug. A new decade began and still construction had not begun.

But at this point at least, it wasn’t public opposition that was keeping work from beginning – instead, the opposition came from beneath, from the decidedly challenging conditions that prevailed under the city.

In his chapter on the metro systems of the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe, Hatherley quotes Lazar Kaganovich, the famously brutal Old Bolshevik who had been put in charge of the construction of the Moscow metro, complaining that “old-regime geology” was hindering progress. According to Kaganovich, “geology proved to be a pre-revolutionary part of the old regime, incompatible with the Bolsheviks, working against us”. If this was the case, then the soil underneath Riga was very pre-revolutionary indeed.

Pēteris Šķiņķis, associate professor at the University of Latvia’s Faculty of Geography and Geology, provided a useful summary of these geological challenges in a recent Latvian-language article on the metro project – “we are in a river delta, which was created millions of years ago. There is no homogenous rock structure – it is completely flaky, made up of dolomite and sandstone. For that reason, at set depths technical fasteners would be needed… it’s not like in Helsinki, where you can drill tunnels in the rock. We have more complicated conditions.”4

The problem Šķiņķis is referring to can best be appreciated from a plane – or from Google Maps. The River Daugava, starting to fan out as it approaches the sea, less than ten kilometres distant, picks a number of small islands out of the city. To its north and east, Riga is banked by a series of interconnected, sprawling lakes, which themselves feed into the Daugava. You can’t leave the city without passing over or directly alongside large bodies of water. (There was once in fact even more water – at the time of its first settlement, it was a peninsula, caught between the Daugava and the Rīdzene, which it remained until the latter river was directed underground in the 19th century).

The resultingly high and unpredictable level of groundwater would have posed technical challenges, and meant a potential risk of stations and lines flooding. Even though there were no plans for lines to run through the medieval heart of the city, there was a danger that sudden fluctuations to the water table could cause the wooden foundations of the houses of Old Riga to start to rot at a greatly accelerated pace, risking the collapse of the buildings above.5

The technical and economic plans for the system were completed in 1980, two years behind schedule – but soon afterwards responsibility for the project was transferred from Megiprotrans to the Lenmetroproekt Institute. Riga’s challenging geological conditions had not a little to do with this decision: the institute was based in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), a city famously built on a marsh but where since 1955 an extensive, and very deep metro system has been in operation.

The trail goes dark at this point – for some time afterwards it’s hard to find a great deal of evidence about the project or how it was progressing. Until 1983, that is, when an article appeared in the Latvian popular science journal Zinātne un Tehnika (“Science and Technology”). Written by the Russia-born engineer Lilija Tracevska, who was involved in the metro project, it gives a glimpse at how the project was conceptualised at this particular stage in its development.

Apparently intended to introduce the project to a general, if informed audience, much of the text is taken up with technical explanations of how the city’s troublesome geology would be overcome, but towards the end we get an insight both into how the project was justified by the authorities, and into the experience of the average commuter in this alternate future. Reading this bit induces the odd, somehow weightless feeling I always get from seeing someone confidently envision their future in my past.

Tracevska points out that, while the population of the city was only around 850,000 at the time of writing, in the summer months it often exceeded a million; thanks to its lengthy, if cool seacoast, Latvia was a popular destination for holiday-makers, with the most popular resort of all – Jūrmala – just half an hour from Riga by train. She extrapolates that by 2000, the permanent population of Riga would exceed a million. At some point during the ‘80s, the two lines originally planned were topped up to three, and Tracevska describes in detail the central eight stations of the first line – which would have been the first section to open. This stretch would have run from Zasulauks station on the left side of the Daugava to a station serving and named after the VEF factory, passing through the city centre along the way.

Each of these first eight stations was to have a theme. Several are vague and innocuous: Zasulauks, which would have been the interchange for overground trains to Jūrmala, is defined as “seaside, health and relaxation”; Raiņa, named for Latvia’s national poet, Rainis (a passionate believer in both socialism and Latvian independence), represents artistic and spiritual work. But a number certainly would not have made the cut a decade later: Oškalni, named after a Latvian communist, represents “the Great Patriotic War”; Kirova station, named after an associate of Stalin with no discernible link to Latvia, was to commemorate “the establishment of Soviet power in Latvia”; and Centrālā, which would have been connected to the city’s railway terminal, was to represent “the friendship of the peoples of the Soviet Union”.

In closing, Tracevska mentions that a competition was to be held in which designs for the interior of the metro stations would be selected; architects from Pilsētprojekts would participate together with colleagues from Minsk and Moscow.

The competition went ahead as planned, and it is the winning images that continue to define the metro project, more than thirty years on. They are almost invariably the featured images for the articles (almost all Latvian-language) that delve into this particular cul-de-sac of the country’s past – immediate clickbait. And there’s a reason for that: they are both stunning and eerie, somehow looking as though they’ve been beamed both from a lost future and from a lost past.

The work of a number of different architects, they nonetheless function as a coherent, complementary set, with consistent attributes. Bold, streamlined, and almost entirely unadorned, most look like they could be entrances to the lair of the villain in some ‘60s sci-fi film. Only Centrālā Stacija features local signifiers – in addition to the blocky pillars and slightly unsettling symmetry that characterises the others, artistic depictions of the grand turn-of-the-century architecture of the boulevards beyond appear, though pushed up to the curved ceiling above passengers’ heads. Raiņa station appears to feature an auseklis – the jagged depiction of the morning star that is one of the many angular “strength signs” (spēka zīmes) that are said to have their roots in Latvia’s pagan history – but, that aside, the city that would have been above them, and the republic they exist in the midst of is almost totally disregarded. We’re in a subterranean world of improbable, bowed surfaces, smooth planes, right-angles and mathematical equations – like going to work through a diagram. The rather unreal vibe is intensified by the fact that the design for Kirova features a few transparent, ghostlike people, gazing upwards or hurrying off for unknown purposes.

At this point, at least, the metro project appeared to have direction and impetus – quite unlike the country that was paying for it, mired by this point in economic and political stagnation under Leonid Brezhnev. Riga’s metro would be a thrilling, propulsive statement; it would also look like the past’s vision of the future.

1. https://theculturetrip.com/europe/serbia/articles/belgrades-metro-and-80-years-of-failure/

2. In 1956 at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Nikolai Khrushchev gave his “secret speech”, condemning the repressions of his predecessor Stalin, and initiating the so-called “Khrushchev Thaw”, during which the regime liberalised to a degree, and some limits on freedom of speech were removed.

3. Taken from an unpublished interview conducted by Mārtiņš Eņģelis

4. From “Metro nerisinātu Rīgai aktuālākās transporta problēmas”: https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/zinu-analize/metro-nerisinatu-rigai-aktualakas-transporta-problemas.a266095/.

5. The risk of the foundations of houses rotting is mentioned in the Latvijas Radio 1 programme “Zināmais Nezināmajā” by geologist Sigita Dišlere: http://lr1.lsm.lv/lv/raksts/zinamais-nezinamaja/rigas-geologija-kapec-neuzcela-metro.a50069/

Will Mawhood is the editor of Deep Baltic

The story of the metro is continued in two further instalments: “Struggle”, which tells the story of the protests against the metro system in the late 1980s and the subsequent restoration of Latvia’s independence, and “Traces”, which considers the unexpected ways that the metro story resurfaces in the contemporary city of Riga.

Header image – Gunārs Melbergs, 1981

© Deep Baltic 2019. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.