by Laima Vincė, HÜTTENFELD

Today I drove out to the Lithuanian Gymnasium in Hüttenfeld, a small village in the Lampertheim region. I visited with Marytė Šmitienė, who taught at the Gymnasium for 44 years, and who together with her husband, Andrius Šmitas, formed the vision and the program for the Lithuanian Gymnasium for decades.

I immediately felt familiar with Marytė again, as though all those years had not been there in between the time when I was a shy sixteen-year-old student from America, and she was my teacher, a young woman from Maryland, who came to teach for a year, fell in love, married, and together with her husband, full of idealism, worked towards a positive vision for the school’s future. Back then all the teachers were idealists. I didn’t know this at the time, but Marytė told me that for many years their full-time monthly pay was 600 Deutschmarks (300 euros) and that was all they had to live on. It was all the school could afford to pay.

I am not particularly nostalgic or sentimental. I am not usually one to go backwards in time and reminisce. However, as we walked through the village to the gymnasium, and then visited the castle, Schloss Renhoff (known to us as Romuva after the Lithuanian pagan concept of paradise), memories came flooding back to me.

I remembered how my friend from Canada, also named Marytė, and I were given a job cleaning house for an older German man in the village. We were paid five Deutschmarks each twice a week to iron his underwear (which I found bizarre, actually), fold his laundry, cook his meals, and wash the floors. For me, five Deutschmarks was a lot of money back then and worth the work. But what I really earned were Herr Thomas’s stories. He had been one of the sixteen-year-olds taken into Hitler’s army at the end of the war, when the war machine was desperate for cannon fodder. He was a soldier on the winter march into Russia.

“Es war so kalt, so kalt,” (“It was so cold, so cold”) Herr Thomas would narrate, showing us his right arm, thin and twisted from frostbite.

He explained that they did not have the proper clothing to endure the cold. All his life he has struggled with injuries from frost bite.

He also had stomach cancer. Every day a crate of beer was delivered to his home. Herr Thomas explained that the government delivered the beer because he had to drink it to cure his stomach cancer. Thinking back as an adult, I can only wonder if this was actually true…

One day Herr Thomas pulled out Tarot cards and read mine and Marytė’s futures. He laid out the cards for Marytė, studied them, and with great enthusiasm told her two things: “You will be a doctor and a millionaire.”

Privately, I doubted either would come true. However, oddly enough, today Marytė is both a Doctor of Psychology and a millionaire from successful real estate deals. Who would have thought?

Then he read my cards. He grew disconcerted.

“You will have a tragic life,” he said. “I feel very sad for you.”

He knotted his brow, laid out the cards again, and came to the same conclusion.

“What?” I thought, “how could that be? Nonsense. Marytė will be a doctor and a millionaire, and I will have only sadness?”

“Your sadness will come from two men, both of whom you will meet in the next few years. Both will love you, but you may only choose one. You will need to choose between them. Do not make the wrong choice. The consequences will be dire.”

“How will I know which one is the right one?” I asked.

“The right one, may call you a Blöde Kuh, but don’t pay any heed, you will know he is the right one.”

To this day, this advice remains a mystery to me… Stupid cow? Why would I ever want to marry someone who called me a stupid cow?

I never had a chance to seek clarification. The next week when I went to Herr Thomas’s house to clean, a woman called out to me from a window above the street, “Der Mann is tot! Tot!”

The man is dead. Herr Thomas is dead.

Just like that. This elderly teenage soldier was gone.

In 1982 there were many armless or legless older men who spent their idle hours convening on the streets in our village, sharing war stories.

They were all gone now.

The farm across the street from the school was gone. We would cover our ears on the days they slaughtered the pigs. Their screams sounded like human screams. The betrayal of trust between pig and farmer in that final moment before death came was simply too much to bear.

Marytė and I walked into the castle parlor. It had been damaged when the castle caught on fire in 1984. I gazed down at the parquet and remembered how on Saturday nights we would hang up a disco ball from the ornate plaster ceiling, turn on strobe lights, and dance, all of us teenagers twisting and swaying lost in our own private worlds, as seventies and eighties music played in the background.

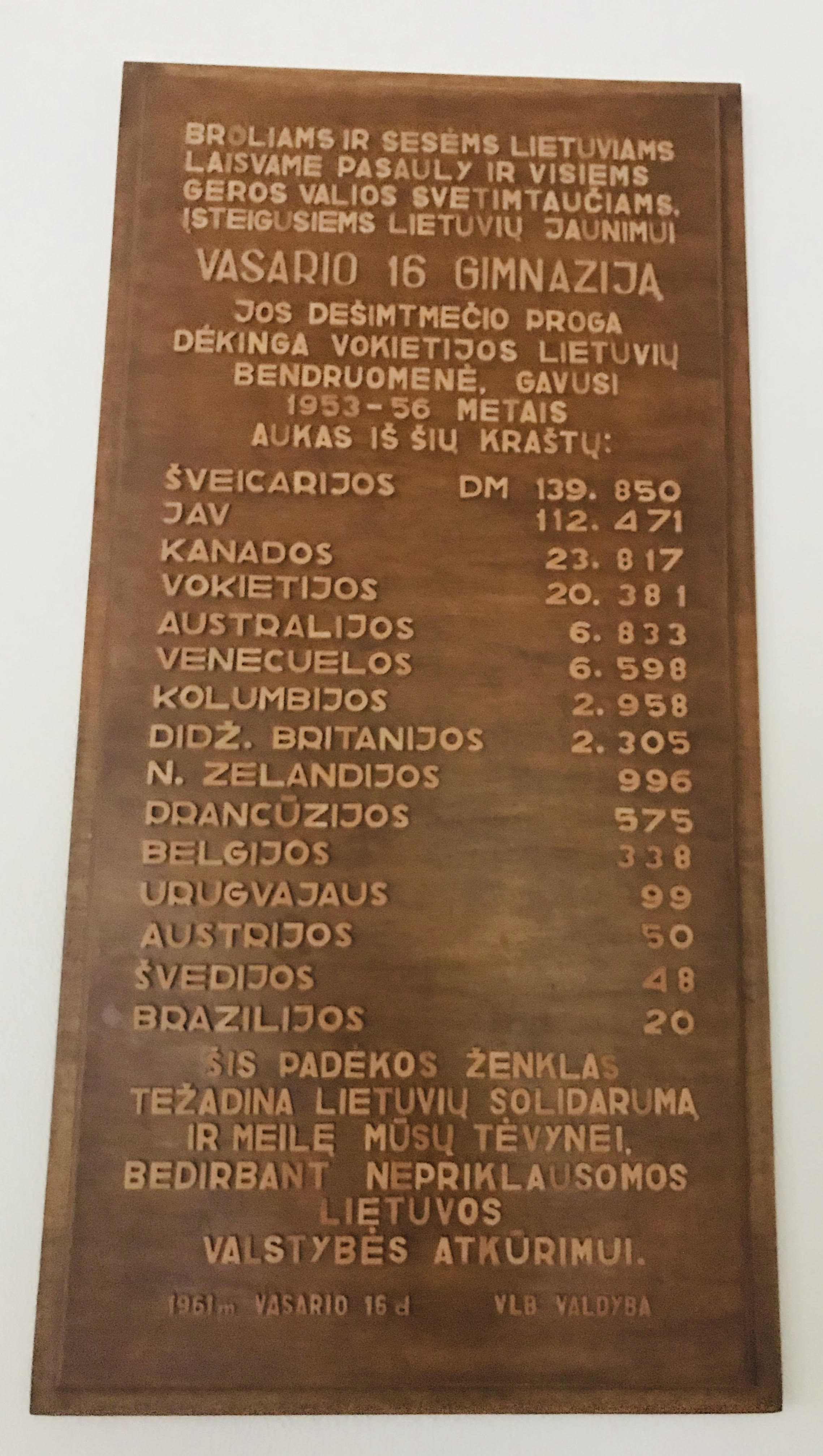

The plaque of the school’s benefactors still hung in its place of honor on the wall. The exact amount of dollars each diaspora community contributed was clearly counted and on display. Brazil, with all its economic instability back then, could only offer 20 Deutschmarks, but even that was duly noted and appreciated. I loved having Lithuanian diaspora classmates from Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia. They were the children of displaced persons, like I was, but their parents’ ships had taken them to South America, not North America.

My chain-smoking tow-blonde Colombian friend Diana told me a story in her lovely Spanish-accented Lithuanian about how her DP mother, then a young girl, boarded a boat to South America, while her family boarded a boat to North America. She thought: “North America, South America, how far apart could they be?” She arrived on a tropical beach wearing a fur coat. She traded her fur coat for a bunch of bananas, ate the bananas, and then set out on the streets of Bogota, looking for work. A Lithuanian priest who had emigrated to South America in Czarist times took her in to work as a maid. That was how her family got their start in Colombia.

Marytė explained that because South American currencies were weak, the school would take them, even though they could only pay a small portion of their tuition.

“Andrius would say that we will just cover the rest,” she explained.

When the first director from Lithuania came to replace Andrius, she stopped accepting the students from South America because they could not pay their tuition.

That was when the old spirit of the school began to change.

Back then we diaspora Lithuanians were a community. We helped each other. We relied on each other. We donated, we gave, we supported. During school vacations those of us from overseas who could not afford to fly home would always find some place to go. Andrius would look through his kartoteka, his card file of emigre Lithuanians in Europe, and pick out a few names. Then he would make a call. That was how I ended up in Munich, in the heart of the Lithuanian underground at Radio Free Europe, over Christmas 1982.

The gymnasium was a center for the Cold War Lithuanian underground but was also infiltrated with teachers and students reporting back to their handlers in Soviet Lithuania. Everyone knew who was on which side. But we all politely got along, nonetheless.

Then there were the dissidents who resided at the school because they simply had nowhere else to go. There was Ponas Lukošius, a tall, elderly journalist with snow white hair, who had trained as a lawyer in prewar independent Lithuania, and who was involved in the anti-Soviet resistance. He ran a sort of information news center out of the Gymnasium. Marytė and I would go see him to borrow newspapers and he would give us chocolate candies with polar bears on the foil wrapping. I was thin and always hungry then, so I was grateful for the calories.

Once Andrius fooled the entire school into believing that the elderly Ponas Lukošius was taking a bride. An older woman came to our school from Berlin—was she a writer? I don’t remember. Andrius put out a rumor that she was coming to marry our dear Ponas Lukošius. We formed a welcoming committee. They arrived together in the director’s car from the train station. We began planning their wedding ceremony in the school park, peppered them with questions about how they met, their relationship, and so on. We were all exasperated when we learned later it had been one big joke on us—a joke that lasted the entire day and into the evening.

Then there were the times we played jokes on our school director, only they did not always turn out so well. Like the time we decided to hold a protest and sing protest songs (why I don’t remember) and camp out in the hallway instead of going to class. On that very day, by coincidence, the state school inspector paid an unexpected visit. After the inspector left, Andrius came out into the hallway, where we were all sprawled on the floor, someone strumming a guitar.

He said to us in a calm voice: “You have lost the privilege to address me as Andrius. From now on, I am Herr Schmidt.” Then he turned around and returned to his office.

Nothing more needed to be said.

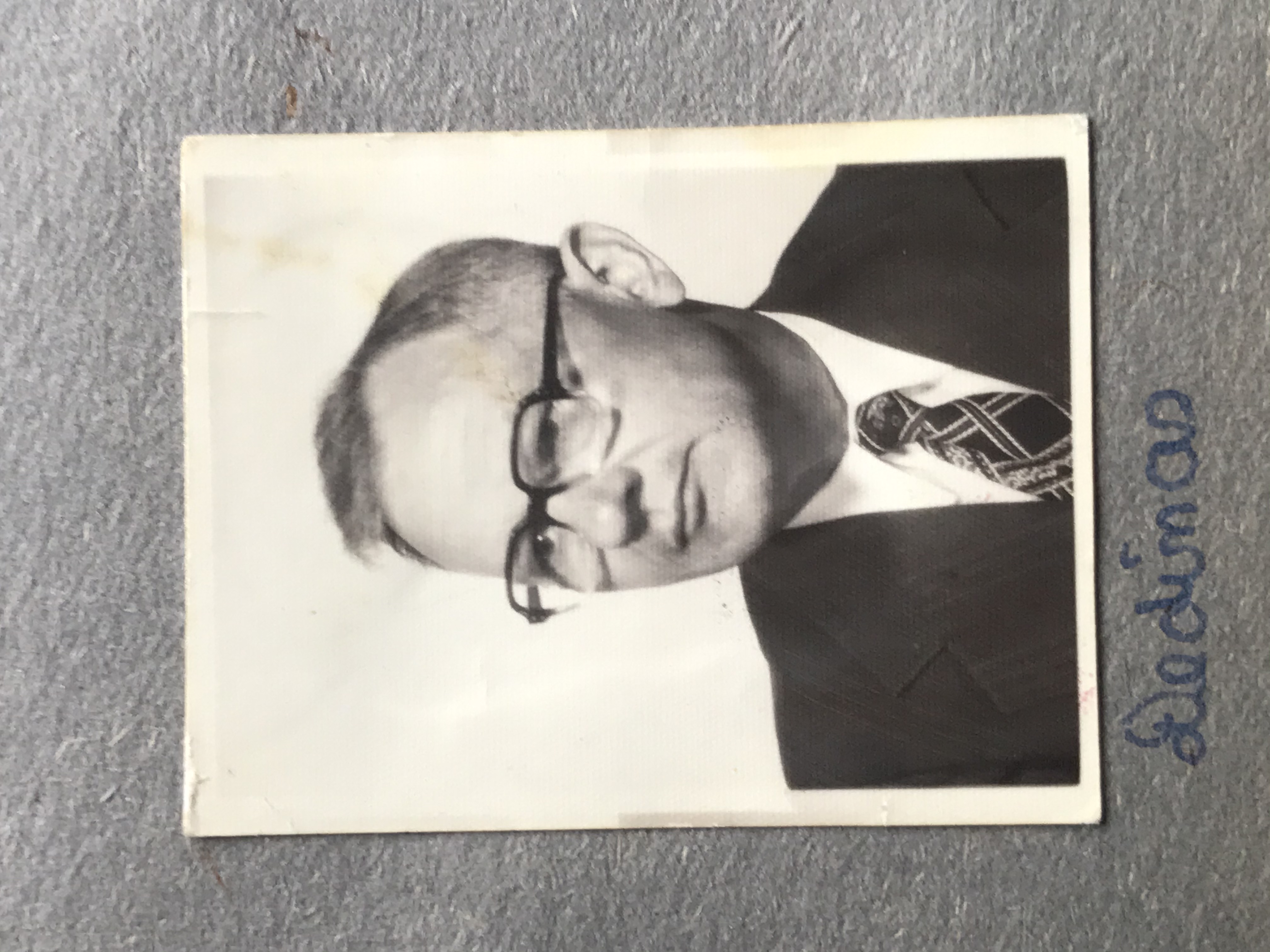

The education I received in my two years at the gymnasium could not be compared with the thorough private school educations students receive today. It was more a school that taught life lessons. One teacher who shaped my character was Father Dėdinas, a priest who survived World War II as a war refugee, operated a ham radio out of his bedroom, loved the opera and sometimes brought us along with him to Mannheim Opera. He was a strict and exacting teacher. If you were drowsy in his class, he’d make you go outside and run around the building three times as the rest of the class watched through the window. He taught three subjects: Religion, Politics, and Lithuanian. His lessons on politics still influence me today. He taught he us to recognize the difference between “Innen und Außenpolitik”—domestic and global politics. In his class, we watched films showing food waste in Europe as people went hungry. In Religion class he taught us about the seven dimensions and where the human mind ceases to comprehend rational thought and enters the realm of the spiritual. Every day at noon he would stop whatever he was doing, stand completely still, and pray for world peace.

One day we came to class and Father Dėdinas told us to sit down and write our parents a letter wishing them a good death. Immediately, the German students were in an uproar. Only a few decades had passed since World War II and in Germany then it was a matter of national priority to teach young people to think for themselves and to argue their opinion. And so, we did, we argued all time with our teachers and with each other.

Father Dėdinas listened patiently until we exhausted all our arguments. Then he explained that in the Catholic tradition wishing another a good death was the kindest and most merciful blessing.

Then we understood.

Perhaps we did not have science labs then, or a proper gym, or even art classes, or music—other than someone cranking out polkas on an accordion. The Lithuanian Gymnasium is a proper school now, fully renovated, with many course offerings. Yet I would not trade those days back then for anything. For me, those years were an eccentric school of life. Oh, but somehow along the way I did learn Lithuanian and German, history, literature, and fell in love with the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke and Vincas Mykolaitis Putinas.

Lithuanian brothers and sisters in the free world, and all others, who in the spirit of goodwill have helped to found February 16th Gymnasium to educate the Lithuanian youth, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of our school, the Lithuanian-German Community would like to thank you for your donations, received from the following countries during the years 1953-1956:

Switzerland – 139,850 Deutschmarks

The United States of America – 112,471

Canada – 23,817

Australia – 6,833

Venezuela – 6,598

Colombia – 2,958

Great Britain – 2,305

New Zealand – 996

France – 575

Belgium – 338

Uruguay – 99

Austria – 50

Sweden – 48

Brazil – 20

May this token of our gratitude inspire solidarity in all Lithuanians and love for our homeland as we work towards the reinstatement of Lithuania’s independence.

February 16, 1961 The Lithuanian-German Community

Header image – class photo from the Lithuanian Gymnasium, 1983 (Laima Vincė second from left). All images credit – Laima Vincė

This is an edited extract from a longer essay which will soon be published on The Vilnius Review

Laima Vincė is a Lithuanian-American writer, poet, literary translator, artist, and educator. She is the recipient of two Fulbright grants in Creative Writing, a National Endowment for the Arts grant in Literature, a PEN Translation Fund grant, and other awards. She earned an MFA in Writing from Columbia University and a second MFA in Nonfiction from the University of New Hampshire. She is the author of a novel, This Is Not My Sky, which was translated into Lithuanian as Tai ne mano dangus (Alma Littera), and five works of literary nonfiction, including Journey into the Backwaters of the Heart, translated in Lithuanian as Mūsų nepalaužė (Alma Littera). To learn more about Laima Vincė’s work please see her website at: www.laimavince.com