It was as a student in the ’70s that I first discovered Sudermann’s Litauische Geschichten in a university book shop that was said to stock all the titles I needed to read for my course. The title intrigued me: these were “Lithuanian Stories,” written in German, but I had come across them in an era when only the Soviet Republic of Lithuania featured on maps. As the daughter of a Lithuanian refugee, I was well aware that few people in the UK had even heard of Lithuania. Why the bookshop had even ordered it in the first place was a mystery – in those days my very traditional course barely featured any works published outside West Germany and much of the literature studied was from previous centuries – but I bought it anyway and kept it. It is only now in retirement that I have finally managed to uncover the story of Sudermann’s Lithuanians.

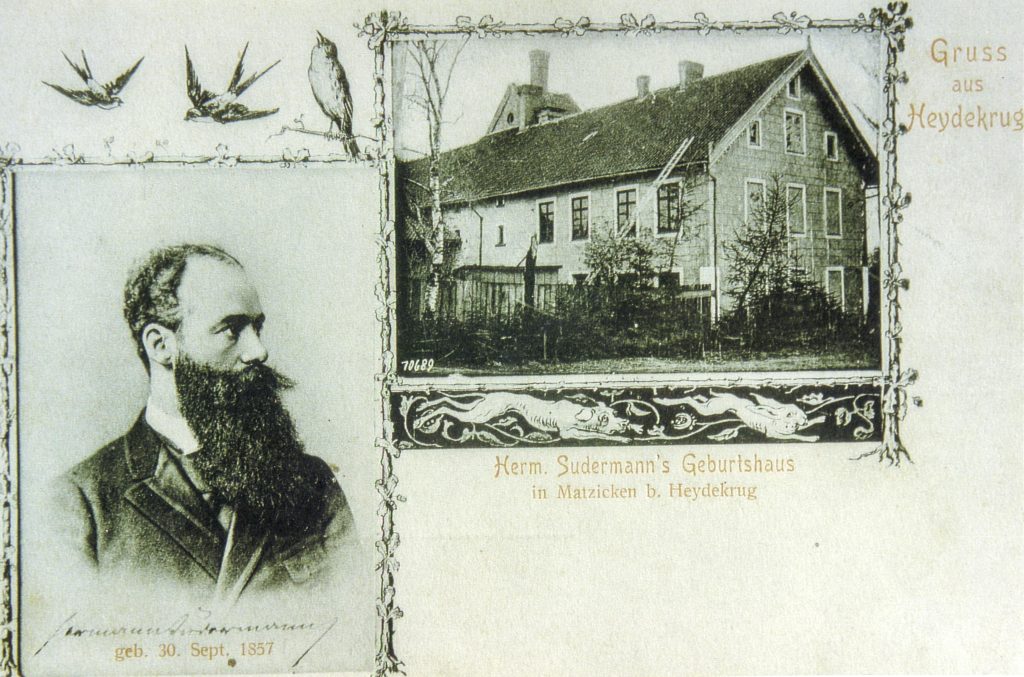

The author Hermann Sudermann was born in 1857 at Matzicken (now Macikai) a village to the east of Heydekrug (today Šilutė) in what was then the Province of Prussia and which today is part of the Klaipėda region in south-western Lithuania. At this time Lithuania as a country did not exist. The territory where Lithuanian speakers lived was divided between the great powers of Russia and Imperial Germany. Although there had always been a sizeable Lithuanian-speaking peasant class in that part of Prussia, Lithuanians were for the most part considered subordinate to the German-speaking gentry and town-dwellers. Sudermann’s own family belonged to the Mennonite community, who had emigrated to the region a century before in search of religious freedom and cheap farming land, so he had no great affinity with the Lithuanian-speakers of the area, nor did he belong to the Baltic German aristocracy who had lived in the area for centuries. He was educated in German at the Realgymnasium (high school) in Tilsit (today Sovetsk in the Kaliningrad oblast of Russia) and he studied later at the university in Königsberg (today Kaliningrad)

Sudermann spent much of his adult life in Berlin, where he worked as a journalist and playwright, although he did return to live in Königsberg for a short period in the 1890s. Whilst his plays are rarely performed today, he did enjoy considerable success at the time, travelling to Italy, Egypt, Greece and India, and they enabled him to buy a villa in the exclusive Blankensee area of Berlin, where he housed his collection of art works. Several stories and plays were adapted for the cinema in Germany and Hollywood during the interwar period, including the silent film The Undying Past starring Greta Garbo, which was based on his novel Es war. He died in 1928.

It was only in 1917, long after he had left his homeland, that Sudermann decided to write the Litauische Geschichten, and in doing so he chose a traditional literary form very familiar to the German-speaking readers of the nineteenth and early twentieth century – that of the Dorfnovelle (the village novella). Works of this genre were extremely popular at the time, reflecting the lives of the newly literate middle and working-class peasantry in disparate parts of the Prussian Empire and Hapsburg Austria-Hungary. Germany only became a centralised state under Bismarck in 1871 and even now the country is a federation of separate states. Many Germans today identify very strongly with their region, and this was even truer in Sudermann’s time. Whilst Berlin had become the capital of the newly formed Prussian state, for many writers of the time, provincialism was an accepted fact of life and, as we shall see later in one of the stories, Berlin was a dream destination for ordinary people in the countryside.

Initially the Dorfnovelle set out to observe and record the lives of country-folk, neither idealising nor patronising them. Realism was important and writers focussed on creating milieu. As the form developed in the nineteenth century writers started to use it as a vehicle to express their concern at the speed of urbanisation and the flight of country folk to the towns. Later still, in the years after World War I the movement grew into something far more sinister with its romanticised views on ethnicity and homeland culminating in the “Blut und Boden” literature of the Nazi era.

Brief references to Sudermann’s life in East Prussia can be found in some of his earlier works but it was only in 1917 at the age of 60 that he chose to write about the world that he had known as a child. Written during World War I, a time of seismic change in Europe, the tales are set in the 1870s, the time of his youth and display a yearning for a simple, rural life, unspoilt by mechanisation and urbanisation.

Before World War I the rights to self-rule of minorities, of nations without a country, had long been a problem for the great powers in Europe. National borders had been drawn with disregard for the linguistic and ethnic populations who lived there. The area around Heydekrug had belonged to the Kingdom of Prussia since the 18th century and the remainder of modern-day Lithuania was ruled by Imperial Russia. In the 19th century, these peoples, together with minorities all over Europe, were striving for recognition. In the Russian Empire the anti-Tsarist uprising in 1863 saw the introduction of repressive language policies. The publishing of books in the Lithuanian language was banned entirely in 1866 and Eastern Prussia then became the headquarters of the knygnešiai (the book smugglers), who clandestinely carried Lithuanian books over the border. Königsberg had long been a centre for publishers of Lithuanian literature and the university there had been a centre for the study of the language. German-Lithuanian dictionaries and grammar booklets were published during the nineteenth century and the university even taught Lithuanian to Lutheran pastors who were sent to the region.

In 1905, it was estimated that between 50% and 60% of the Heydekrug region were Lithuanian-speakers; however, in Sudermann’s circles German was dominant and reigned as the language of governance, of the commercial world and of national and international communication in the region.

In the tales Sudermann is writing as an observer of the Lithuanian community, rather than as a member. The collection comprises four tales, “Die Reise nach Tilsit,” “Miks Bumbullis,” “Jons und Erdme” and “Die Magd”.

“Die Reise nach Tilsit” (Journey to Tilsit) tells the story of an outing made by a married couple to the city of Tilsit, and features a long description of the boat journey inland made by a Lithuanian peasant couple from their fishing village on the shore of the Curonian Lagoon to the bustling German city. Ansas, the protagonist, has formulated a plan to kill his wife Indre on the journey, in order to marry their maid who has become his mistress. As the journey progresses so the tension rises, for Indre is aware of his plan, although quite how Ansas will execute it remains a mystery to her and to the reader.

The story is interesting in the way Sudermann illustrates the differences between the city-dwelling Germans and the Lithuanians who live in the countryside. Ansas and his wife are Lutherans and prosperous in their community but they lack the sophistication of their German neighbours and their journey to Tilsit is like one to a foreign land. They have never seen a train or the railway, and when they see the locomotive they dream of travelling as far as Berlin. They marvel at the shops in Tilsit and buy tourist souvenirs, sample German delicacies at the pastry shops and ride a carousel at a fairground. They attend a concert given by a German regiment, although Indre is concerned that this is intended for a German audience and not for a Lithuanian woman in her “margine” – the traditional Sunday best skirt she wore on her wedding day. The Germans at the concert comment on how much alcohol the Lithuanian couple consume – Ansas orders wine rather than beer so that he might be seen as an elegant gentleman and the Germans at the next table comment audibly about Indre’s “Lithuanian” appearance and her naive charm. Indre, especially realises that she is different: she might be Lutheran like the Germans and hopes that her youngest son might grow up be a pastor, but she still silently invokes the gods of ancient Lithuanian mythology. Laima is mentioned, as are Pukys and Atwars (Pūkis and Atvaras are both nature spirits.) It is interesting too to note too how Sudermann uses a germanised spelling of such words. There is no “w” in the Lithuanian language, yet the village where Indre and Ansas live is written as Wilwischken.

The story of “Miks Bumbullis” tells of the trial of a lawless poacher and smuggler operating in the borderlands between Prussia and Russia, who murdered a gamekeeper during the Joninės festival. As a result, the gamekeeper’s ward, a young child, is left homeless and alone. A false alibi leads to more complications and ultimately to Miks’ downfall. This is the tale of a wily peasant who exists in his own Baltic/Lithuanian milieu, yet is legally a citizen of a country where the hierarchy is rational, foreign and distinctly Germanic. Miks’ forays back and forth across the border show his disregard for his rulers – everyone in the region smuggles, the frontier is artificial and has been imposed upon them. His trial is in German and much is made of the need for translation and the peasants’ faltering attempts at German. However his guilt and his crime are real – the force of natural justice and the need for attrition are evident in the account of the German trial but are clearer and more visceral in the scenes where Miks is pursued by Giltinė, the goddess of death, by the visions which haunt him of the young girl in her coffin dressed as a bride, with her wreath of rue and the echoes of ghostly folk songs.

“Jons and Erdeme” tells another peasant story, that of a couple who work hard and even steal to rebuild their farmstead on a reclaimed marsh so that their two daughters can have a better life; however, as a result, their children grow selfish, lazy and unscrupulous, abandoning and even stealing from their own parents and leaving them to face old age alone.

The tale of “Die Magd” (The Maidservant) reflects the status of the Lithuanian peasantry in the nineteenth century. A young girl is seduced by the local German bailiff and frantically searches for a husband for her unborn child. After losing the man she would have chosen, she enters into an unhappy marriage. In desperation she attempts suicide, rowing into the “Kurisches Haff” (today the Curonian lagoon stretching down from Klaipėda to Nida and beyond) and is found still alive with the baby beside her by a kind family who take her in. The story ends happily when she marries the son of the family who has recently lost his own wife in childbirth.

The society and traditions of those German-speaking East Prussians featured in Sudermann’s work were soon to disappear forever. After World War I and the dissolution of Imperial Germany, the northern area of the region, the Memel, was initially governed by the League of Nations. But in 1923 it was annexed by a newly independent Lithuania, even though the population was overwhelmingly in favour of a union with Germany. Pro-German parties had an overall majority of over 80% in local elections at the time. The census of 1925 recorded that 43.5% of the population were German, 27.6% were Lithuanian and 25.2% considered themselves Klaipėda/Memelländisch. A policy of Lithuanisation followed in the inter-bellum period and considerable unrest ensued between the different ethnic and linguistic groups. This situation became even more fraught when Antanas Smetona came to power in 1926 and the area became a centre for those opposed to the president.

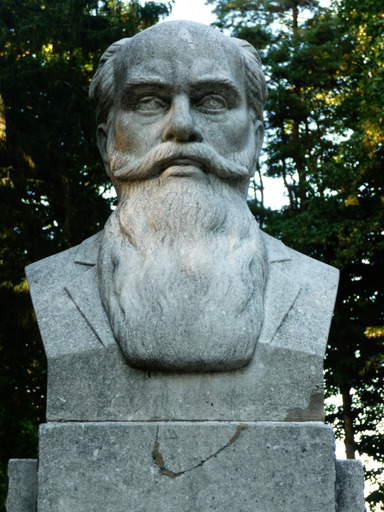

By 1938 the Lithuanian government had lost control of the situation in the territory and the Memelland was returned to Germany. Most Lithuanian-speakers then left the region. When the Soviets invaded at the end of World War II, the majority of German inhabitants had already fled westward. The Soviet government expelled over 3,500 German-speakers to East Germany in 1951 and others were repatriated to West Germany in 1958. Large parts of the once grand city of Königsberg (Kaliningrad) were destroyed during World War II and the area is now an isolated Russian enclave, only accessed by means of the infamous Suwałki gap. Today part of Sudermann’s former Landkreis of Heydekrug is now in the Russian oblast but the northern section is Lithuanian (Klaipėda). Today there are only a handful of German-speakers left in the area, although the area remains popular with German tourists. Place names have changed and there are few signs of the legacy left by Sudermann and his contemporaries, although there is a small museum in Macikai dedicated to Sudermann, and tourists can also visit the brewery which his family owned in the town.

The Hermann Sudermann Stiftung in Berlin continues to promote the study of Sudermann’s work today. His country house in Blankensee just outside Berlin is now in use as an educational centre and every other year the foundation awards the prestigious Hermann Sudermann Prize to a playwright writing in the German language.

The copy of the Litauische Geschichten which I bought all those years ago and which I still have today was a Harrap edition from 1971 (costing £2.75!) with notes and an introduction in English by Dr B. J. Kenworthy of Aberdeen University. Sadly, this edition is long out of print and there were never any lectures or seminars on Sudermann in my day, although Sudermann did warrant an entry in The Oxford Companion to German Literature compiled by one of my tutors, Dr Mary Garland. It would seem today, in the English-speaking world at least, that the study of Sudermann’s works is most definitely niche. Whilst the stories are widely available in German today – a quick glance at the listings in Amazon indicate a variety of hardback and Kindle editions of the stories – there are no recent editions in English and the last commercial translation seems to that of Lewis Galantière in 1930. The stories have also been translated into Lithuanian but are not currently in print, although used copies are available on internet sites.

Margaret Drummond grew up in the UK in a Dutch/Lithuanian family and studied French and German at university. For many years she taught languages in London secondary schools. Now retired, she volunteers as a translator for a charity.

© Deep Baltic 2022. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.