Photographer Andrew Miksys has Lithuanian roots, but grew up in Seattle; he has lived in Lithuania since the ’90s. Since his move to Vilnius, Miksys has covered a number of subjects that might fall under the radar of a casual visitor to the region, including an acclaimed series on makeshift nightclubs in small Lithuanian towns. In parallel to this for over 25 years he has been taking pictures of the country’s small but resilient Roma community, eventually collated in a book named after the distinctively Roma concept of baxt. Baxt is a Romani word thought to have Persian origins, its possible meanings covering a range of nuances from luck to destiny to karma. In a new, updated edition of BAXT, Miksys remembers: “The project started in the winter of 1999 when I came across a Lithuanian Roma family in Vilnius. The people were friendly, I took a few photos, and went home excited to learn there were Roma Lithuanians. But when I started asking questions about Lithuanian Roma, I heard all the usual stereotypes about Roma people being thieves and liars.”

In recent decades, the Roma population in the country has numbered no more than a couple of thousand. Miksys’s photos take as their settings some of the small community’s main population centres across Lithuania, including the district of Kirtimai just outside the capital, originally a place where Roma caravans stopped when travelling through Vilnius; the southern town of Eišiškės; and the small settlement of Žagarė on the border with Latvia, where Miksys now lives. Miksys recounts in the book how his Roma neighbour in Žagarė presented him with a live turkey as a welcoming gift on a national festival, but also more traumatic events, including the gradual demolition of Kirtimai and eviction of its inhabitants from 2004 onwards, supported by local politicians. We share some photos from BAXT, as well as an excerpt from Laimonas Briedis’s foreword to the book, where he reflects on the interplay between Lithuania’s perceptions of the Roma and outside perceptions of Lithuania.

(Taken from Light of Home: the Roma in Lithuania by Laimonas Briedis)

The Roma have always been a small but not invisible minority in Lithuania, with pictures of their camp sites populating archives as well as the popular imagination, even though most Roma were settled and living in cities and small towns alongside other peoples of the country. The war and its immediate aftermath, however, was a fateful exposure for the Roma: by some accounts, about half of the Roma population perished in the Nazi-conducted genocide, known as porajmos in the Romani language, meaning devouring. Subsequently, the Soviet regime offered them little freedom or space to lead a full fledged life, and in independent Lithuania, Roma by and large have been regarded as incomers, being pushed away from civil society by prejudice and administrative inequity. To that end, the official (historical) memory of Roma in Lithuania is slight, mostly augmented to fit secretarial resolutions of the European bureaucracy.

Across Europe, the Roma are the most numerous (indigenous) minority, which corroborates the local character of the group. Conversely, widely accepted (mis)representations of Roma have shaped the way the community is pictured and seen in Lithuania. While Mérimée’s Lokis* made no inroads into the consciousness of Lithuania, his early novella Carmen turned a concept of Roma into an enduring stereotype. Mérimée published Carmen in 1845, but set the story in Andalusia of 1830, in the era before the advent of photography and in a place of blinding sun. The namesake heroine of the story is a Roma femme fatale, propelled into fandom by the 1875 opera of the same title by composer Georges Bizet. In contrast to Lokis, which Mérimée wrote as a no-risk escape into an unfamiliar Sanskrit-laced milieu, Carmen is authored with the confidence of an expert about all things gitanos, as Roma are known in Spain and France. There is no narrative connection – real or fictional – between Carmen and Lokis, other than being birthed by the same creative mind. Yet as I see it, the two stories found within the same oeuvre but separated by the age of photography (Lokis is set circa 1867) capture the relationship between two characters – Lithuanian and Roma – as being kept apart by misconstructions and concocted appearances. At best, Roma in the Lithuanian imagination are exotic wanderers, as Lithuania is relegated to the meandering margins of Europe. The error is to assume that there is no juncture between the two.1

Both Lithuania and Roma entered the European purview during the Middle Ages. By chance, Roma are first mentioned reaching the shores of Europe (specifically, the Greek island of Crete, the mythological birthplace of Europe) in 1323, the same year Vilnius is known to be founded as the capital city of Lithuania. And while (contemporary) Lithuania has never been strongly associated with Roma, within the expansive past of the country, Roma have been noted since the fifteenth century. Pointedly, BAXT frames the casual convergence of Vilnius and Roma in the light of erasure. Many photographs in this album are from the locality of Vilnius known colloquially as Taboras (in Lithuanian), a term that in the region of Lithuania has been exclusively used to denote a Roma domicile. In the past, taboras meant a caravan and/or a camp formed by horse-drawn wagons, as in a Roma family and community on the move. In contemporary Vilnius though, Taboras came to designate a permanent settlement – an actual location near the airport but on the wrong side of the tracks – set up in the postwar years by the Soviet administration on the semi-industrial periphery of the city. The residents of the settlement, mostly but not exclusively Roma, called it Parubanka, following the area’s pre war Polish name of Porubanek; while on the map, it appeared to be a part of Kirtimai, a Lithuanian translation of the Polish place name. In both languages, the place name means glade or forest clearing, highlighting the local work of the axe.2

The word taboras is different, its origins going to the biblical narrative of the Holy Land, while at the same time pointing to the heavens. Mount Tabor in Galilee is the assumed site of transfiguration, known as metamorphosis in Greek, where Jesus appeared to his three disciples in the radiance of glory. Referred to as Tabor Light, the event (a miracle by all accounts) pairs with Resurrection in eschatology. The uncreated nature of the light goes against the physics of photography, while in some corners of Christian Orthodoxy, it is also taken to be a forewarning of the fires of hell. The transplantation of Tabor to Vilnius is a circuitous affair that goes well beyond the scope of this collection. But among many hard-to-pin down facts and transactions, it involves a belief in the end of times, irresolvable theological disputations, crusades against the heretics in the kingdom of Bohemia, a town built on a hill in 1420 named Tábor (in the Czech language), the deployment of a wagon-fortress, roving armies in the territory of seventeenth and eighteenth century Poland-Lithuania, camp followers, a series of rulings against wandering in the Russian empire, Roma perseverance during the Nazi occupation, and finally, a decree by the communist government of the Soviet Union to settle the Roma for good, which eventually led to a settlement on the margins of Vilnius. Most Roma who populated Parubanka came from somewhere else, reflecting the immigration patterns of the city in that period, in which a vast majority of inhabitants were newcomers. It is unclear when and how the name Taboras came to be applied to this Roma settlement, but the place name has been in use unofficially for decades.

Perhaps deceptively, I see Taboras in juxtaposition to Kalvarijos (Calvary), a parkland vicinity on the other side of Vilnius reimagined in the seventeenth century as a local memento of Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem. Kalvarijos is a choreagraphed site of peregrination dreamt up in the style of baroque, whereas Taboras is an unscripted dwelling place built up in rustic fashion. Dynamited by the communist regime as an unwelcome love-token to the Holy Land, the Vilnius Calvary was resurrected soon after the Soviet times. Taboras, however, no longer exists. It was completely erased some years ago as being tumbledown and vice-ridden, but also hazardous to the future-oriented image of Vilnius. Its Roma residents were displaced around Lithuania. In many instances, the images in the album are tributes to the eyes and faces of the Roma who live no more in Taboras. In this light, BAXT is a portrait of a lost home. Hence I view the photographs of Taboras in the spirit of James Baldwin’s quotation: “You don’t have a home until you leave it, when you have left, you never can go back.” Yet being at home, in Svetlana Boym’s definition of the sentiment, is “to be comfortably unaware of things, to know that things are in their places and so are you. It is a state of mind that doesn’t depend on an actual place.” Bobrowski’s* lyrical rendering of the Roma home as “sails in the stiff forest of masts” illuminates these photographs’ narrative thread of a sense of the Roma home as family heritage. The vision of an empty room in one of the photographs (not in Taboras but in the small town of Žagarė) sums it all up: a portrait of a dead woman, decorated with a stripe of black draped across the frame, hanging on the wall in a peopled world, here mute as the grave. This keepsake is a secret, about a fate, told in the spirit of baxt.

1. The word gitanos has become ingrained in Lithuanian consciousness as a quest for novelty. Gitana (in a feminine form) is not an unusual first name in Lithuania; and while the masculine form – Gitanas – sounds off-the-wall; it has been made unremarkable by being the given name of the current president of Lithuania. By habit and tradition, Lithuanians still use “čigonai” for Roma, a word of unknown, but, possibly, Persian or Greek, origin. However, it is out of the question for a Lithuanian to have an official first name Čigone or Čigonas.

2. In this, but in name only, it resonates with the clerical (Catholic) evolution of Vilnius as the original site of a destroyed (pagan Lithuanian) sacred grove.

* A short work of fiction by the French author Prosper Merimée. According to Briedis, “Titled Lokis (meaning bear in Lithuanian), the novella has it all – a gloomy (wooded) location, rape by a wild beast, a deranged wedding, savage passion, kidnapping, transmogrification, slaying, and, to frame the story, a link to India.”

* Briedis earlier quotes the German poet Johannes Bobrowski’s memory of seeing a Roma encampment in Lithuania: “tents, frayed with the echo / of dead voices, torn mouths of bells, / tents with laced flaps, freezing / with age against the sky”

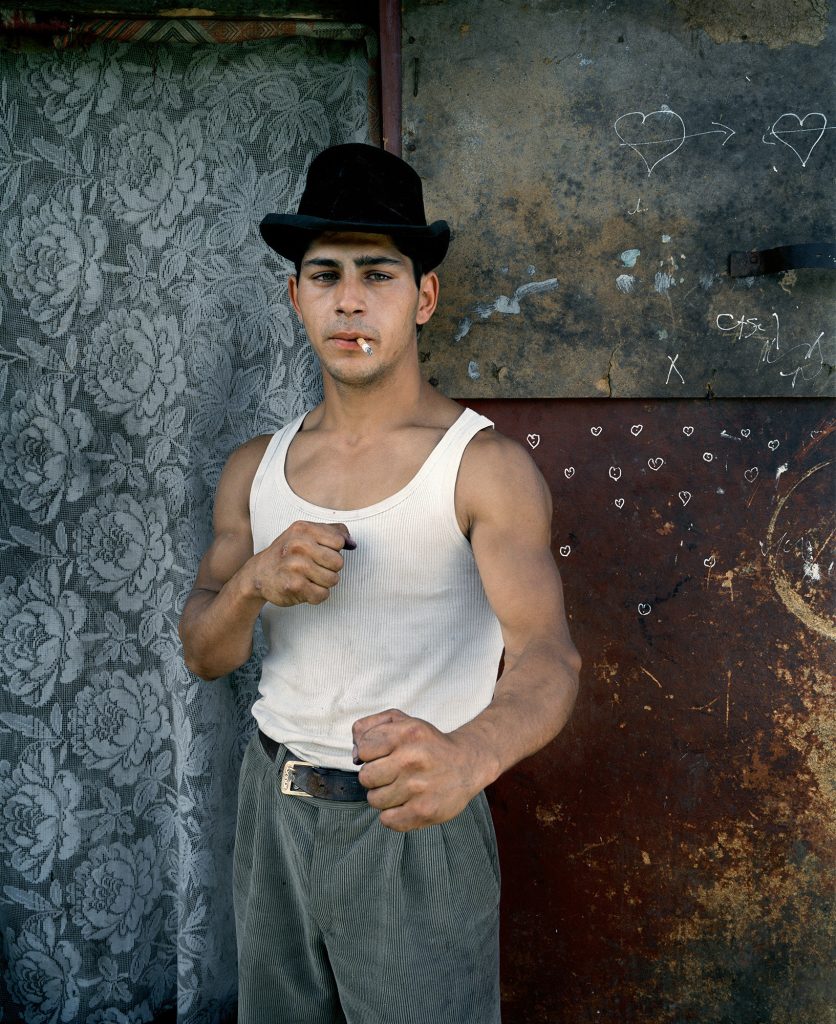

Header image – Sandus, Žagarė (2019)

BAXT will be launched at MO Museum in Vilnius on 27th March. You can find out more about Andrew Miksys’s work on his website.

© Deep Baltic 2025. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.