by Joel Burke

Today, Estonia is well known globally for its leadership in tech and e-government. The country is home to one of the highest rates of startup formation per capita in the world, with Estonian entrepreneurs helping to build well-known companies like Skype, Wise, Bolt, and Starship Technologies. In policy and civic tech circles, Estonia is hailed as a leader in digitalizing government services, enabling solutions like fast and free online tax filing and i-voting via the web. The country is perennially at the top of lists related to the ease of doing business and taxation policy and is always among the leading nations, usually peers in the Nordics, when it comes to low levels of corruption and high levels of internet freedom. Its education system is well regarded and the 2022 PISA educational survey which was published in December 2023 put Estonia at the top of the charts in Europe and eighth worldwide.

That in 2025 Estonia would be a global leader across multiple domains is not happenstance, but due to long-term investment and the creation of a policy environment that enabled and rewarded experimentation, education, and entrepreneurship. Numerous reforms, from the economic shock therapy initiated by former Prime Minister Laar which eliminated subsidies and forced the creation of a functional market-based economy to investments in foundational e-services like digital identity and the X-Road, have been responsible for modern Estonia’s success (along with a bit of good timing and luck). However, underrated in everyday discussions about the country’s success is the impact of multi-decade investments in education reform and experimentation.

As far back as 1995, a few short years after the country regained its independence, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, then serving as ambassador to the United States but later to become president, floated the idea of a campaign to connect all schools in Estonia to the web, along with a tech literacy program. This was immediately after seeing the release of Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina’s Mosaic browser, the first truly user-friendly tool enabling the average person to access the internet. Ilves had instantly grasped the scale of opportunity for Estonia in the nascent internet economy and saw it as a place where Estonia was on a level playing field relative to America, Germany, or even Finland, and where it could potentially leapfrog larger but slower-moving nations. Ilves’ idea would become known as the Tiigrihüpe (Tiger Leap) program and was introduced by the president of Estonia in 1996, with funds allocated for the program soon after. By 1999 the program had accomplished its primary objective: connecting all schools to the web. While the connections weren’t always the fastest, it gave every Estonian student the possibility of exploring the world through the internet and understanding the potential of the web.

The impact of the program on Estonian society was profound, even if it took years to pay off. According to tech Estonian entrepreneur Ott Kaukver in an interview with Stanford Libraries, the “Internet broke down the boundaries, the borders of countries. Now you could do a global thing while sitting in Estonia.” Providing that access eliminated the relative isolation felt by many Estonians. And the technical education component did wonders for the domestic tech industry. Today, it is difficult to find a founder of one of Estonia’s many tech companies who didn’t get at least some exposure to the web and technical skills through the Tiger Leap program.

Also impactful was the effect that the program had on the education system itself. As part of the program huge numbers of teachers were trained in technical skills, helping expose older people who had never used a computer, let alone the internet, to the web. This has been critical as the government has worked tirelessly to digitalize government services, with the education system being no exception. Starting in 2002, the eKool program was launched as a central online hub to connect teachers and families with realtime attendance tracking, grade management, and more. Unfortunately for Estonian students, “the dog ate my homework” excuse doesn’t fly in a country where everything is accessible online. The eKool program, along with other tools like Stuudium – which allows for the creation and sharing of lesson plans, document management, and more – have helped to create a more efficient education system in the country, one that is more adaptable to changing curricula and circumstances, whether the advent of AI or a pandemic.

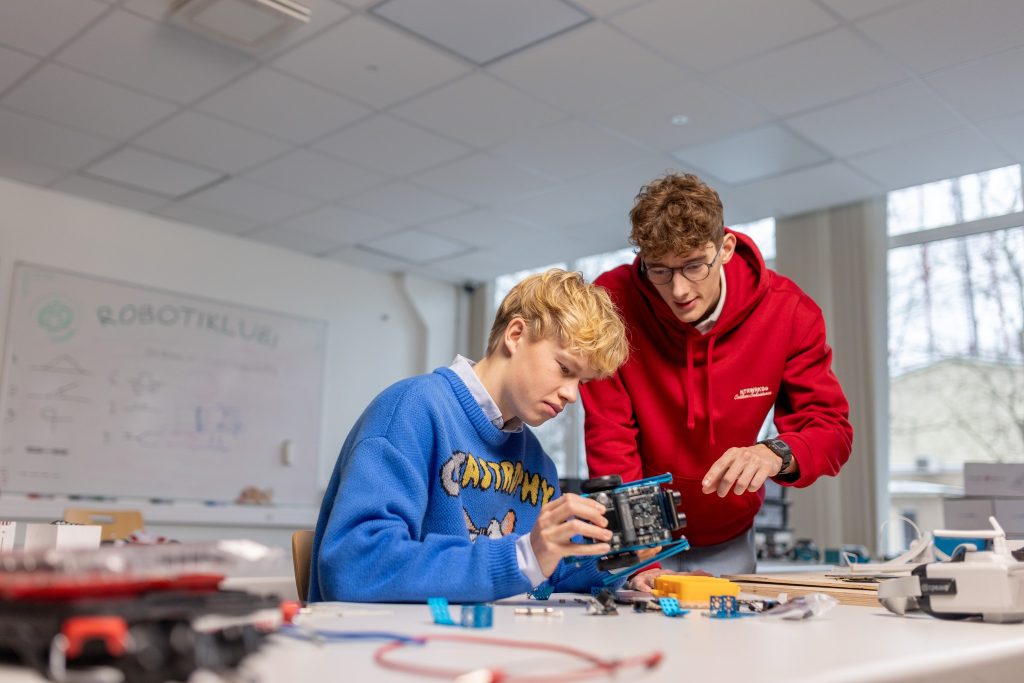

However, one might imagine that the impact of a program started in the ‘90s would be waning as the rest of the world caught up and also began closing the digital divide in schools and teaching technical skills. But importantly, Estonia has continued to innovate when it comes to its curriculum, as the success of the Tiger Leap campaign demonstrated the potential of societal-level educational reform. In 2012 the country launched the ProgeTiger program, which educated youth from their earliest days in school in programming, robotics, and other STEM topics, in an effort to expose them to opportunities in technical fields. And unfortunately, being in a dangerous neighborhood with a history of occupation by their revanchist neighbor to the east, Estonia has also had to train the populace with further “dual-use” skills – those with both commercial and defense applications – to prepare in case of an invasion. As of mid-2025, schools across Estonia will teach high school students how to operate drones – a subject added to the national defense curriculum in high schools, which was made compulsory in 2023.

With generative artificial intelligence being all the rage, the country has naturally begun investing significantly more time and resources into ensuring that the population has the skills necessary to navigate workplaces replete with AI tools, in an effort to create a future-ready workforce. To do so, in early 2025 the Estonian government partnered with OpenAI to bring a specialized version of ChatGPT to high school students and teachers, with plans to expand to vocational schools. The program, dubbed AI Leap 2025, is still nascent but expectations are sky high that Estonian students will not just be digital but AI natives by the time they leave school. Undoubtedly, they will be more prepared than most students in the West whose education systems are loath to adapt to or adopt any new technology, despite the fact that it is almost guaranteed that a significant portion of students are already leveraging AI tools in some way.

Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father of modern Singapore, once likened skilled professionals to “megabytes in Singapore’s computer.” As a small country, Estonia has long looked for any way to multiply the number of megabytes in their own computer, and upskilling the population with the expertise necessary to navigate the technologies of the future has been a surefire way to do so. For countries that wish to emulate Estonia’s success, creating educational institutions that are innovative and adaptable to new technologies and ways of working (and learning) might be one of the highest leverage opportunities for long term investment.

All images credit – estonia.ee

Joel Burke is the author of Rebooting a Nation: The Incredible Rise of Estonia, E-Government, and the Startup Revolution and a research fellow at fp21, a think tank focused on transforming the process and institutions of U.S. foreign policy using evidence. Previously, Joel was an AI fellow in the office of Senator Mike Rounds and served as Head of Business Development for the Republic of Estonia’s e-Residency program.

© Deep Baltic 2025. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.