Narva is a particularly interesting place to discuss minorities and identy, being more overwhelmingly minority-majority than any large city in the Baltics. Right on the country’s border, divided from Russia only by the Narva River, it is more than 90% Russian-speaking, a place where it is relatively unusual to hear the Estonian language in the street, and where Estonian citizenship is held by less than half of the population – with large numbers either being Russian citizens, or “non-citizens”, having not obtained citizenship of Estonia or any other state after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The lively discussion was moderated by Deep Baltic editor Will Mawhood, and on the panel were Kristina Kallas, director of Tartu University Narva College; Jiri Tintera, architect of the city of Valga in south Estonia; Francisco Martinez, an anthropologist who has previously researched Narva; Madli Maruste, lecturer in architecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts; and Ivan Sergejev, Narva city architect – all living and working in Estonia, and either representatives of minority groups themselves or particularly knowledgeable about the subject.

WM: Estonia is an ethnic democracy – I believe it would be correct to describe it as such. Do you think there’s any possibility of it becoming a civic democracy – which is the difference with America, as you’ve said. For example, there’s no official language in America; there is this idea that wherever you come from you can become American.

KK: Not yet, anyway [an official language in the US]

WM: Not yet, true – this is possibly in the near future, I don’t know. But is there any possibility of this for Estonia? Or is it just that the history is too different? You’re shaking your head, Jiri.

JT: No, because there is only one reason why Estonia is still here – it is a nation-built state, because you can behave like this if you are a really big country on your own somewhere. But if you are still obliged to define your identity next to big countries – like Russia – you have only one thing on top of which you can do it – so I’m very sceptical about this.

WM: So there’s no other basis for the country to exist, other than the fact that the majority of people here are Estonian?

KK: But there are no civic democracies in Europe. Can you name a country in Europe that is a civic democracy?

WM: Switzerland?

KK: No, it’s not. It has a very clear identity of forming out of four. Switzerland is very protective of itself against foreigners – it’s not like the United States, which is a country of immigrants, or Australia, which is made up of immigrants. Every country in Europe is a nation-state – a clean and pure nation-state. Even France, which pretends to be a civic nation state, is very ethnic, in this sense – it’s not French ethnicity; it’s the language, it’s certain values that they promote, and you have to adjust to those values if you want to be French. It’s not that everyone can be French – no, you can be French if you do this, this, this and this. Or you can be British if you do this, this, this and this. Britain is even going back in a way, introducing language tests for foreigners, which never used to be the case – now, if you want to get long-term residency in Britain, you have to pass an English-language test, you have to do British history. You have to prove that you kind of are integrating, that you’re British enough.

FM: We’re kind of talking about two parallel phenomena. The first one is that Estonian society has difficulties in accepting difference. That is because Estonian identity is understood as if it was in danger. We are in danger because of Russia; we are in danger because we have been invaded by Germans, by Swedes, by Danes… So Estonian society accepts differences with difficulty. And the second point is the way that ethnicity and nationalism, which are zombie ideas that belong to the past, but are still circulating, are being re-activated nowadays as a reaction to globalisation, as an answer to global uncertainties. And I say this because of right-wing populism, the failure of the European project as a trans-national project… and there is a step back now. So these are two parallel phenomena that in Estonia and the Baltics complement each other – the way the society closes itself against a bigger country or a bigger neighbour and the way globalisation is affecting our societies.

IS: I think it’s really perverse though how we’re entering into this era of e-residency. The real reason is that I think Estonia wants to choose its citizens, and that’s essentially what’s going on with the e-residency programme. Because there was this slogan “ten million in ten years” or whatever – we’ll become a ten-million nation in a certain amount of time; that’s what this e-residency thing is all about. But they’re virtual residents. I find it really kind of mind-blowing; it’s crazy: you will argue that you are a ten-million nation, although 8.5 million of you are not even there. How does this layer on top of everything we’ve been talking about? It’s the same way that Estonia has been choosing the immigrants it receives. It’s the same thing – choosiness of whom to take in, and based on what kind of criteria. I don’t know about this whole national or civic state, because with e-residency, I can see – I don’t know the proper philosophical term for this, but it’s not civic and it’s not national, it’s something else.

WM: I think it’s worth pointing out that these people [Estonian e-residents] are not becoming citizens – they are obtaining residency for business purposes; I don’t think they’re necessarily expected to identify with Estonia in any sense.

IS: A lot of people are Estonian residents only, but they still make the weather in a lot of ways, so I’m wondering when that border is going to be crossed.

KK: I agree with you, in the sense that citizenship as a part of identity or belonging is devaluing itself, because it’s becoming just like a passport, with a certain number of rights.

WM: In Estonia or everywhere?

KK: No, everywhere. With globalisation, people are much more transnational. So people can have several citizenships and several passports; and it’s becoming more and more common, especially in Europe, to allow dual citizenship or multiple citizenships. So a passport is just a document that lists your rights in certain territories – so I have certain rights here, and then I have certain rights here. If I don’t have citizenship here, I have residency and that gives me certain rights – I have access to business; I have access to finances, to social rights, to education. It used to be the case that only citizens had all their own rights – all of this, educational, social rights, civic rights, political rights; this was all just backed into citizenship. Today, citizenship is left with only one right that nobody else has, which is the political right to vote. Every other right is already divided into all different categories – permanent residents, temporary residents. Human rights for everyone; it’s not only for your own citizens. It used to be only for your own citizens, human rights were part of citizenship – not everybody had universal human rights. And now it’s just spread around, and it creates difficulties for the nation state to define who your people are.

FM: Passports still matter – we can say that to the Syrian refugees crossing the border into Greece, or we can say it to Francisco Martinez, who has no access to hospitals in Estonia, despite having been here for more than five years. So passports still matter.

KK: But if you’re an Estonian citizen and you don’t pay taxes, you don’t have access to hospitals either. It doesn’t matter – it’s not the citizenship; it’s your residential, tax-paying rights.

FM: But you can make business with e-residency.

KK: But as an EU resident you have access to healthcare, because you pay taxes. So the passport doesn’t give you rights.

FM: It’s not as simple as that – because it depends on the country. Your original country, in my case Spain, is supposed to pay for your hospitals, but I have been for so long living abroad…

KK: No, it’s not, it’s not. Your social security is based on your tax. The country where you pay taxes – that’s where your social security is. And it’s not the passport – if I’m an Estonian citizen and I don’t work or I just came as a tourist, I don’t have free access to healthcare. I pay, because I haven’t paid taxes in Estonia.

FM: If you are resident in Estonia and you work as a freelancer you don’t have access to hospitals.

WM: I feel we’re getting into quite a technical discussion here, which I would like to return to maybe a bit later…

IS: But it’s fascinating, don’t you find, because those small things really put you in your place. Tiny things: where you can get coverage or you can’t get coverage; where you get certain rights or don’t get certain rights.

JT: I must disagree with you, because I was living for one year in France, in Paris, and there I had a really strong sense of new incomers being refused, because there are so many new incomers that they don’t want more, so I didn’t feel good, even though I spoke French and the culture was very close to me, but there was really this feeling that “OK, you are other”.

And I came here, and I haven’t had any problems up to now. And that’s another topic that I wanted to mention – we talk about minorities in Estonia – and about those minority who came here as the majority. I have friends who were born in Russia – they came ten years ago; they came because they wanted to come, so they went through this process which every incomer has to go through. At the beginning you must explain why you are here, and then your family – then once you are accepted, your family are accepted and you reach the point where you decide whether this is a good place for you or not. And you leave or you stay – if you stay, then you accept your new identity. You can be Russian, you can be Czech, you can be Finnish. But those who people who came here during the Soviet Union, they came as the majority, so they didn’t go through this process, and this is the difference – so we can’t really compare this to immigration.

WM: Well, I’d like to pick up on this and go back to the discussion we were having earlier – this question of a civic state vs. ethnic state. Because although, as Kristina pointed out, we don’t really have civic states in Europe, it is true that Estonia and Latvia are the two countries in the EU with by far the highest proportion of minorities – you have about 30% I think in Estonia, and in Latvia it’s around 35%. This is far higher than other member states. Is it possible for Estonia to be a successful ethnic state without making the minorities Estonians? Is it possible to integrate these people, and will the state be a failure if this doesn’t happen?

MM: Now we get to this question of who is Estonian; how do you measure this? Basically it comes down to the bloodline, doesn’t it? Who can claim that they are Estonian? Do you have to have three, four generations pure Estonians in your ancestry? Because there aren’t any Estonians like that; we are all mixed – these “ethnic Estonians”. We are all mixed, but this is not discussed, because the country has really been built up as a nation state, not as a civic state, so it gets into these really big questions, like who can claim they are Estonian.

WM: But as Kristina points out, there aren’t really any properly civic states in Europe, so for Estonia to become a civic state would require for it to do something entirely new in the context it’s operating in.

KK: No, I think what it requires is to redefine what it is to be an Estonian. You don’t have to change the nation-state concept, the understanding that we are a nation state – because most European states are nation states. You just have to redefine what it means to be Estonian. Does it have to mean that three generations back, everyone is Estonian in your family? Or does it mean that Jiri can call himself an Estonian and that’s fine, or this Maksim who was in Pskov who said he is an Estonian? Yes, good.

And in terms of statistics, 30% and 70% – these are just the statistics, and they actually doesn’t reflect reality; it doesn’t reflect reality, because it just draws a border. Someone just decided – “OK, this is where we draw the line. This is a majority; this is the minority” But that’s not really how people identify themselves in reality. Because this is based on national census statistics, and in the national census you are given the question “what’s your ethnicity”, and there are multiple choices and you can choose only one. OK, take the Estonian government ministers: two of them would probably tick “Russian” – Jevgeni Ossinovski [Minister of Health and Labour] and Mihhail Korb [Minister of Public Administration] – and that means “minority, excluded; we are an ethnic state”. But that’s not true; the reality is much more complex – I guess both of them would say that they are Estonians, or Russian-speaking Estonians, or Russian-background Estonians. And you don’t have those options in the population census. I have been arguing with the EU statistical board about this a lot, because as a researcher, it frustrates me, because I don’t get data that actually represents reality as such.

MM: The data is really wrong, I also got this when I was doing my PhD, because there is not an option to put these kind of hybrid identities. Because most of these people who we regard as the Russian minority, they are also really mixed – they have all kinds of roots in all kinds of former Soviet societies, or even Estonian roots. But you can’t put this option in the census: that I am kind of mixed identity, hybrid identity

WM: So you think generally if someone is half-Russian and half-Estonian, has one parent from each ethnic group, they would generally choose Russian, because they would identify with the minority?

KK: No, I chose Estonian, but I was very upset that I couldn’t choose anything else. So my mother is Russian and my father is Estonian; I grew up bilingual, but the Estonian state tells me that I have only one box which I can choose. This is the box where I have to jump – and I don’t like this box, but they don’t give me any other box. The research from Soviet times shows that in the Estonian case, when it was an Estonian-Russian mixed family, usually it was Estonianised – the children became Estonianised. In Ukraine, it was the opposite – in Ukraine, the children became heavily Russified if it was a Ukrainian-Russian mixed family. In Moldova, they became Russified as well. But in Estonia, there were kids who identified themselves as Russians, but more often as Estonians

FM: I believe it’s not possible to make Estonian society more inclusive in the current terms. And I believe this because those who are in power at the moment – that generation, so to say – justify themselves in a revanchist paradigm against the Soviet Union. So until a generational change happens in Estonia, and they seize the power with a more neutral approach towards the past, a more inclusive society cannot happen. An example is that in 26 years of restored independence, only four ministers have been either Russian-speakers or of Russian origin.

JT: But it’s changing fast.

FM: There is a new generation, the so-called “children of freedom”, who have a more neutral attitude towards the past. Once they seize power and they don’t legimitise it by a revanchist attitude towards power, but by knowledge, the paradigm will shift. The problem, as I see it, is not only that it is delusional, this approach towards how cohesive or monolithic Estonian society is; the problem is that it has direct effects, like unemployment, like disinvestment, like HIV, like social problems in certain areas of Estonia because of this revanchist paradigm, which at the same time produces effects of marginalisation – the fact that there abandoned apartments, the fact that there are empty houses. It reproduces this feeling of disintegration, it reproduces this brokenness, it makes some areas more marginal, and that is not being resolved, in my opinion.

[Ten-minute break]

WM: So I wanted to pick up on Francisco’s comments about the various social problems that are experienced by the minorities in Estonia, and I think this would also be true in Latvia. But one thing I wanted to ask is that I’ve read a lot of different texts and analyses and articles about the Russian-speaking minority in Estonia, and they usually conclude that “there must be more integration”, but they’re almost invariably very vague about this actually entails – how should this people be integrated? And do they necessarily want to be integrated?

IS: I think you’re asking the question the wrong way, because if you’re saying “does someone want to be…” – that’s assimilated, is the word you should be using. “Integrated” is when both parties merge.

WM: But the question I’m asking is: how should this be done? It’s generally presented that the government should do this or the Estonian state. How would this be done?

FM: I have an example – this morning when I was coming here by train, I had the chance to talk to an architect who was sitting in front of me. And at the beginning he said “Narva is a place full of potential” and then he add “I have been working with Narva for ten years, and there have been some great projects, but none of them work, because of being alien” – because of local people feeling that they have been transplanted, or sent from Tallinn or elsewhere to Narva. And I told him that perhaps one of the reasons is that there is not simply potential in Narva, but there is reality. There are people there, there are circumstances, there are interests, there are desires, there are needs. And then he said “actually, that’s the key”, that’s the key – and that’s what Ivan is doing now, and Ivan is working well to, connecting the architectural union agenda with the actual needs of people by involving this very local people – and speaking the local codes, not simply by language but also by non-verbal communication. So I wonder, what would be your take on this, Ivan?

IS: I mean I have no idea; I just do whatever I like to do, and if it turns out well I’m happy. I think there is a lot of implicit messaging coming along with my presence here that I’m not aware of or don’t want to be aware of – I just do my job, and I try to do it well. That’s all I care about.

WM: Jiri, you’re Czech, do you feel the need to integrate into Estonian society?

JT: I’ll answer this one later. I have one thing that I really must talk about. You spoke about empty buildings and disinvestment or underinvestment, and you connected this to the problem of minorities or different identities, but my research shows that it has nothing to do with this. Because you have towns or small villages with exactly the same problem of shrinking populations everywhere in the south-east of Estonia, and they are mostly [ethnic] Estonian. So you can’t easily put these things together. What is really happening in Estonia, and in my view this is the main problem, is that Estonia is concentrating itself to one point – Estonia is changing into a one-city country. And, from my point of view, this is nothing to do with different minorities: Tallinn is almost half-Russian, so you can’t connect those two things.

FM: That’s partly true, but you are missing and ignoring and important point, which is the negative associations of Narva. And I’ll give you a small example: the energy plant in Narva is allowed to pollute because of being in an area populated by Russians. No other place in Estonia would be allowed to be as polluted as Ida-Virumaa [the county which Narva is in, which is around 80% Russian-speaking].

WM: So you’re saying that the power plant here is unusually polluting?

FM: I’m saying that the level of pollution in Ida-Virumaa is much higher than the rest of Estonia – that’s a fact. And that this is partly due to negative assumptions related to ethnicity and so-called minorities.

KK: I think you’re going a bit too far here – because the fact about Eesti Energia is that this is producing electricity for the whole of Estonia. So of course if it was in Võrumaa [in south-east Estonia] and they were polluting as much there, I don’t think that would be any different. Because the power is in Tallinn – why would they care in Tallinn if you were polluting in Võrumaa so long as they have their electricity?.

FM: Well, it happens that the main prison is in Ida-Virumaa; the most polluting industries are in Ida-Virumaa; unemployment is in Ida-Virumaa; HIV is in Ida-Virumaa…

KK: No, the main prison is in Tartu.

JT: Valga is dealing with the same negative identity as Narva. If you say the name of Valga, the connection in the mind of the average Estonian is that this is a place where nothing is happening, buildings are collapsing, and there is nobody going there. I don’t see the connection with these minorities here.

KK: But I want to add to Francisco’s comment – I very much agree with you that Estonians want to see potential in Narva, but they don’t want to see the reality of Narva. This I completely agree with. Because the reality, they don’t like it, so that is why they are trying to draw the curtains on it and pretend that it doesn’t exist. They want to paint a different picture of Narva, which is fine, in a way – I don’t have such a big problem with this, except that although they paint a picture of Narva different from what it is today, they don’t do much in order to get there – to that picture. It’s all talk, and not much action, in that sense. The political elite is also talking about Narva in terms of potential, not in terms of reality, but I don’t see any action, in that sense – to bring out this potential and do something.

WM: Because one point you’ve made before, Kristina, I’ve read you commenting on this, is that often if a process of integration does take place in Narva, if a Russian-speaker learns Estonian to a very high level, they generally leave, and move to Tallinn or somewhere else. So is integration necessarily a solution to the problems of cities like Narva – or Valga?

IS: It’s kind of like this anecdote when an HR person comes to the boss and says “if we pay for all of these people’s courses in higher education, then they’re going to leave – what are we going to do?” And the boss says “if we don’t pay for these courses, then they’re going to stay – then what?”. It’s the same thing here. So does integration help or not? It kind of works both ways. You can be very direct with them – you know, you teach them Estonian, they leave.

I’m here; I know Estonian. I left, and I came back. So in that case, we can’t make these 100% assumptions of “OK, this is bad – let’s stop”. And with all due respect, I think stopping integration would be just plain stupid.

KK: But what is expected of integration – I think this is not clear. Because like every kind of a problem between two people who don’t agree with each other, and there is an argument, there is a fight. You go to a psychologist and what the psychologist does is sits you down and says ”you accept ten things about the other person; you accept ten things about the other person. You might not like them, but you have to accept them”. And then you go on, and I think this has happened in society as well. So, in the Estonian case, Estonians set their terms – let’s call it this – set their terms to Russians. You have to learn the language. This was one thing, but the other thing which is even more important than the language, I think, for Estonians is: you have to accept the fact that Estonian state is here to stay. This is something that if you don’t accept this, there is no talk of integration with you whatsoever.

So what are the terms that Russians are expecting from Estonians? Because integration is both ways, so there is something that Estonians also need to do. And I think what Russians are expecting and Estonians have not done that well so far is accepting that we are here to stay, first of all. We’re not going anywhere or assimilating or disappearing. Don’t close the blinds, we’re still here. Even if you close the blinds, we’re still here – you can hear us! We’re here to stay and we have to participate. You have to accept the fact that Estonia is a multi-cultural, multi-religious, multi-lingual society. And this is a paradigmatic change in the heads of Estonians which is very slow to come – because they don’t have to do it, because they are in power. Because if you’re a minority, integration is never equal. There is always someone who is in a less powerful position who has to do more, and someone in a more powerful position who does not have to do nearly as much. But my argument right now is that Russians have done a good job – a lot of marathon-running in the last 25 years, in learning Estonian, accepting that the Estonian state is here to stay; trying to adjust their identity from being the majority to the minority; trying to fit, accommodate somehow. And I argue that the ball is in the Estonian court, for the Estonians to say, “OK, we have to make a step now as well”.

WM We’ll go to you in a moment, Ivan, but I wanted to ask you, Madli, a lot of your research has been connected with what you’ve called “the children of freedom”. Do you see that this is something that is happening with the younger generation of both ethnic Russians and ethnic Estonians in Estonia, that they are accepting these things that Kristina has outlined?

MM: What I actually wanted to say is that this discussion is using a lot this kind of official discourse – we are talking about “the Russians”. But they are not some kind of monolithic group – and also there is not a monolithic group of Estonians. And what we are not discussing here are these kind of socio-economic differences, which really play a big part. It’s really connected with this example of e-residency as well, because it can be applied for only by those who can afford it, who are in a higher economic position. And even in the Estonian group, people who are in a lower socio-economic position, they can’t have health insurance, even if they are Estonians, in Estonia. So there are so many layers.

WM: So you would say the ethnicity is almost irrelevant, or the language spoken, in this case?

MM: It’s not irrelevant, but there are so many other aspects in play which are really connected to economic and social power. That really put people in these different kind of positions of power; in a way, you can buy yourself citizenship.

WM: But do you feel that younger Estonian-speakers – if we say, rather than Estonians, do have this sense that Kristina outlined, that the Russians are here to stay and that this is OK?

MM: Again, I can’t speak of one monolithic younger generation, because there are so many differences – again, regional differences. I did interviews with young people in Tallinn, in Tartu, in Narva. And even they said that they have very strong kind of city identities. They identify more as a Tallinners or a person from Lasnamäe, or a person from Narva. And they even have different kind of identities between themselves. So the young people from Narva were saying to me that “when we go to Tallinn, we feel that we speak kind of different dialect or different language or different slang, and we don’t even understand each other, and we are kind of different”. So there is not this kind of monolithic group. Also among these young people, they have very different education levels and they come from very different socio-economic backgrounds. So there is not such a group that represents either Estonian or Russian young people. And I feel that this discourse is really missing from our public discussion, because we’re always talking about the Russians, the Estonians – Russian youth, Estonian youth, but there are not such categories really.

FM: There is an exhibition on at the moment in Tallinn called “Children of the New East”, curated by Siim Preiman, a friend of mine. And one of the points made by Siim is that those who were born after ’89 grew up with different cultural references, and as a complement of everything that Kristina mentioned is that also history is more than a rhetorical background because of the way that history was rewritten after the year ’91. Especially for the inhabitants of Narva, who moved to Narva in the ‘50s and the ‘60s and the ‘70s, and they didn’t feel they were doing something wrong; they felt they were moving to a different city in a part of the same country. So the way that the Soviet past, the Soviet world has been reduced to an experience which is abject and wasteful, it doesn’t help to integrate those people who were born in the Soviet Union and have, in the case of Narva, a grey passport [given to Estonian “non-citizens”].

One again, a generational change is very important here because of a lack of negative associations towards the past, and these people grew up with different cultural references, different scales, but also with a more local identity – like being part of Lasnamäe, being part of Mustamäe [another Soviet-era district of Tallinn], being part of Narva, being part of Tartu at a local-scale which is not contradictory to being Estonian or Russian or European or global.

WM: Well, this question of local identities is something that I think is really interesting, and that I wish we had more time to discuss, but I don’t think we are going to be able to today. Ivan, you had something you wanted to say, and then I think we’ll go to questions from the audience.

IS: I’m a little late with what I wanted to say, but at the beginning we were talking about this post-imperialistic state that Russians are in, and I think this Estonians are in a post-victimised state. So one culture is trying to say “we’re so great”, but actually we’re not, and the other still can’t get out of the state where they were the victims. I think a lot of Estonians still hasn’t realised that they’re here to stay, or that the country of Estonia is here to stay, because sometimes you still get this feeling that Estonians are still concerned for their freedom, although it’s been a bunch of time. And I understand why because historically it has happened a bunch of times in the past. But I think those two things are in touch with each other – that’s why we have most of the conflict we have. I think if we were just one big culture and then there was another kind of little chunk of another big culture, the situation would have been very different.

Audience Member: I have a question about the language. We didn’t touch too much on language. We talked about citizenship, and then you talked about socio-economic issues, but I think it’s a lot about the language. Because the language decides what kind of global media you are [in] and then comes all the values and things. Both sides using the same language or being in the same language area or field – that’s much important than everything else you have spoken about.

IS: Actually, I do agree with this. It’s like this joke – if you go to France, everything you say, just start with “bonjour”, and then continue in English. It’s kind of the same thing: if you speak the language, you show so much respect for the culture that your citizenship, any sort of religious affiliations, whatever – it doesn’t matter anymore, because you’ve made the effort to speak my language. It saves a lot of trouble, it gets a lot of doors open. And I completely agree with you here, I think language is paramount, especially when you’re speaking about Estonia, which is one million speaking the language.

KK: It’s also changing, as I’ve observed among the young generation. Because in the 1990s, what happened with the linguistic space in Estonia was that the Russian language was completely forced underground, out of the public space – everything in Russian was deleted overnight bascially. So Russian language in the public space – no, no, no, everything was replaced with Estonian. And so the Estonian public space was very Estonianised, and this caused a little bit of exclusion to the Russian minority, because suddenly their language was not acceptable. It was not OK even to speak loudly Russian, because that was not acceptable. But it’s slowly changing, as I see now, especially in Narva here.

The interesting thing is that in Narva College, where we have Estonians, Russians and foreigners all working together, we don’t always share three languages – not everyone is tri-lingual. There is always a combination of two, and then you always need to combine the meetings in terms of what two combinations do we operate in this meetng – either it’s English-Russian or Russian-Estonian or English-Estonian. Quite often it happens, as I observed in Ukraine, that you have this functional bilinguality where you use both languages at the same time in a meeting. I thought with Estonian and Russian that this could never happen because these two languages are kept in two boxes, and I come to Narva and here it is. A person speaks in Estonian during the meeting and the other person replies in Russian, and then the other person speaks in Russian and they reply in Estonian. And it goes on like this in Narva College meetings, and everyone understands perfectly. This kind of linguistic repertoire – it has become more acceptable to express yourself also in Russian. It used to be the case that everyone was kind of afraid even to say “let’s use Russian a little bit”, because everyone was jumping on you. And it’s changing now; it’s getting easier.

You can see this also in – it’s a small step, a tiny step, but still it’s significant – that more rights for the Russian language are being given back in certain areas. So, wow, you can read medical information for your pills now in Russian. You’re laughing, but I think ten years ago, this debate in parliament would have ended with everyone shouting at each other. Or you can apply for legal aid – free legal aid from the state – in Russian now. Of course there were parliamentarians when this debate was going on who were making speeches about how the Russian language is sneaking back because we are allowing them now to fill out their applications in Russian. There is this fear, this psychological trauma, related to the Russian language.

FM: It is partly justified, because of history.

KK: Yes, I’m not saying they’re wrong, but people have psychological traumas related to the Russian language.

FM: It’s a key issue because of access to the Russian media, and the contradictory – not simply different, but contradictory – versions about, for example, what’s going on in Ukraine and so. But I am very optimistic because of what Kristina mentioned, and also because of the young people in my classes, and what I have seen with my friends. Today I was talking to Andra [Aaloe – from U], and she said that she regrets not having learnt Russian. The same with my wife: she regrets not having learnt Russian in the ’90s because of this revanchist atmosphere. So I am very optimistic about these changes.

KK: Estonians have started accepting people if they don’t speak Estonian and they’re Russian. If you accept the fact that the Estonian state is here to stay – that’s fine, you are allowed not to speak Estonian, as long as your political statement regarding the Estonian state is correct. That’s what I’m saying about Russia Today or Russian news: the problem is not that they watch it, the problem is the what kind of message about Estonia is sent through it. Russia is questioning the right for neighbouring countries to exist – Ukraine, Estonia. There is this constant underlining of “OK, we’re not sure that these countries should exist, because they are not democratic, because they are fascist…” – painting the picture of the country not being really a country. And this is what Estonians can’t accept – not the fact of it being in Russian, or that it’s a Russian TV programme, but the message that comes through from there.

IS: This is actually fascinating. There are two things I want to say. First, there was this recent YouTube phenomenon – I don’t know if you guys saw it: there was this Russian kid, here in Narva, who did this rap song and blew up the media, regardless of the language, because everyone was like “holy shit – he actually likes it here”.

WM: This was half in Estonian and half in Russian, right?

IS: The refrain was in Estonian, and a few phrases, but really it was in Russian.

KK: The message was that “I am a Russian and I love it here”.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ppy2RJb53EA&w=560&h=315]

IS: And so everyone loved the song. But the second thing about language which I find really ironic, is that there is a lot of interest on both sides in knowing each other, but because they don’t speak the respective languages, they don’t communicate. So for example, in Narva, all the newspapers are constantly wondering what the Estonians are writing or thinking about them. While in the Estonian language – like Sirp [Estonian cultural publication] had a special number dedicated to Narva – Narva had no clue. There were like three people in Narva that I know who knew that this issue was even there – a whole issue of Sirp on Narva, just on Narva. Basically the people who were interviewed for it, they knew; nobody else knew. It was in Estonian, so nobody here read it, so nobody knew that there was an interest by the media to know more about Narva. More recently, there was an entire series of articles in Eesti Päevaleht [Estonian daily newspaper] about Narva – again, pretty positive. Or maybe not positive, but asking the right questions at least – not just like “Narva is so bad, what shall we do with this fallen creature?” It was more like: there are problems, there are good things, so what’s going on here? And again most of the population had no clue.

So again, I find it ironic, in a very evil way, that there is actually a lot of interest from Estonia. Or like these guys from Channel 2 today who came here for the Estonian Academy of Arts open house. They were saying “every time we have a programme about Narva, the viewership goes up”. So there is an interest in what’s going on here, and there is an interest here in what’s going on out there, but because the languages are different, it doesn’t mesh. So it’s weird, and I don’t know – if there was one thing I would wish for Narva, it would be for someone to translate stuff at both ends, and be like “yo, this is about you in this paper, and this says this – you’re cool. And vice versa”. I personally have been trying to do that a lot – anyone I’m friends with on Facebook know that all my posts are in three languages – all of them, regardless of what I’m posting. Exactly because the two sides have no idea what the other is talking about.

FM: I think that little by little that is changing – look at this Narva residency, look at this debate, look at Narva College. We are moving in the right direction.

IS: I know, it’s so inspiring – but I’m waiting until this hits the mainstream, the main discourse. That what I’m really looking forward to.

The first part of the discussion can be read on Deep Baltic at this link. It will also shortly be available in Estonian in Müürileht.

U19-Deep Baltic is available from selected outlets in Tallinn and Riga, and also accessible online

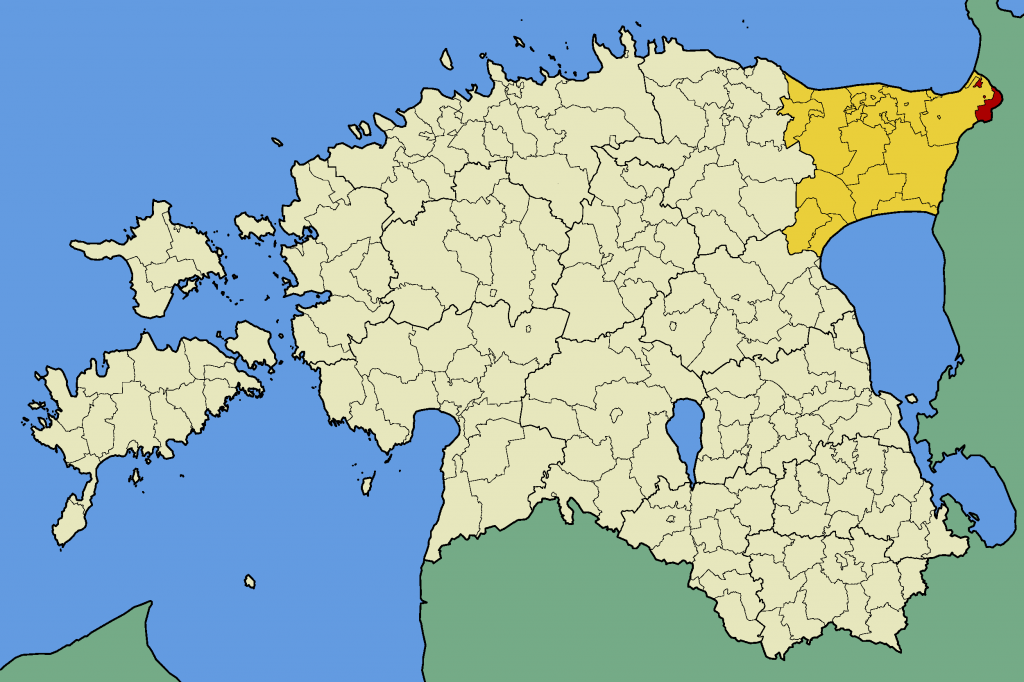

Header image – Narva (highlighted in red) and the country of Ida-Virumaa (highlighted in yellow) on a map of Estonia [Creative Commons]

© Deep Baltic 2017. All rights reserved.