Estonian is among the smallest state languages in Europe, with just over a million native speakers. But historically, there have been at least two distinct strains spoken in Estonia – literature published in Tartu from the 17th to 19th century was written in a language differing significantly from that spoken in Tallinn. North Estonian came to dominate in the 19th century and became the basis for modern standard Estonian, while South Estonian declined, not being taught or promoted by the state.

South Estonian has historically been divided into the Tartu, Mulgi and Võro dialects – of these, the only one to retain a significant number of native speakers (tens of thousands) is Võro, spoken principally in Võru and Põlva counties in south-eastern Estonia. Võro activists argue that it differs so much from standard Estonian that it should be considered a separate language, but this is not reflected in law, which states that Estonian (based on the northern variety) is the only official language. But Võro continues to be a living language: the Võro-language Song and Dance festival, Uma Pido, first took place in 2008, and has now been held five times, and literature is regularly published in the language.

Kadri Koreinik, an academic at the University of Tartu specialising, among other subjects, in the Võro language, and Sulev Iva, a Võro activist and teacher of the language, spoke to Deep Baltic’s Will Mawhood about the history of the language and culture, its differences from Estonian and the present situation and prospects of the language.

I understand that historically Võro has often been thought of as a dialect, but now it’s generally considered to be a separate language. It’s famously hard to define where a dialect ends and a language begins, but what are the reasons it’s argued to be distinct from Estonian?

Kadri Koreinik: Despite contact- and standardisation-induced changes (NB around a century of Standard Estonian schooling), Võro maintains many of its typically South Estonian features and differs from (standard) Estonian in several aspects: different phonemes such as the glottal stop, affricates, some diphthongs, vowel harmony preserved [unlike in Estonian, which does not have vowel harmony], some inflectional differences, numerous lexical differences, negation. Calculations based on pronunciation, morphology and basic vocabulary demonstrate that only about a fifth of Võro overlaps with Estonian. But this comparison contrasts spoken Võro recorded in the mid-20th century with standard Estonian and ignore recent variation (and heavy borrowing from Estonian on one hand, and the enrichment of standard Estonian with vernacular words, on the other) in Võro.

Sulev Iva: Võro definitely differs linguistically enough from Estonian to be an independent language and this fact is recognised by most leading researchers of Finnic languages. I have considered and called my mother tongue Võro a language all my life, and the Võro Institute and other Võro organisations have also from the very beginning very deliberately spoken about the Võro language and requested recognition from the Estonian government of Võro as an independent regional language. This unfortunately has not yet happened, despite a couple of official attempts at getting legal recognition for Võro.

According to census information from 1998, there were 70,000 native speakers of Võro – but historically it has been much more prevalent in south Estonia. What are the main reasons that the number of speakers has dropped over time?

KK: Please do note that only 40% of the total of approximately 75,000 (according to the 2011 census) reside in the Võro-speaking area. After the 19th-century modernisation and nation-building (the “one nation, one language” ideology and policy), dialects were seen as rich resources for Estonian but not as languages for their own sake. (The process of folklorisation, which makes native dialect speakers consider their language and culture from a different perspective: turning everyday practice, including maintenance and change into folklore, to be collected and investigated, stored and preserved as unchangeable). Soviet-era language planning in Estonia further marginalised variation and dialects – due to linguistic purism, i.e. limiting or getting rid of alien features in a language by language policy (ideologies) and planning (schooling, pre-correcting, etc.) measures. The decades where the shift from Estonian-Võro bilingualism (which was mentioned by Ferdinand Johann Wiedemann, one of the first Estonia-based linguists of German-Swedish origin, in the mid-19th century) to Estonian were most intense only took place from the 1960 to the 1980s, with urbanisation and the spread of mass media.

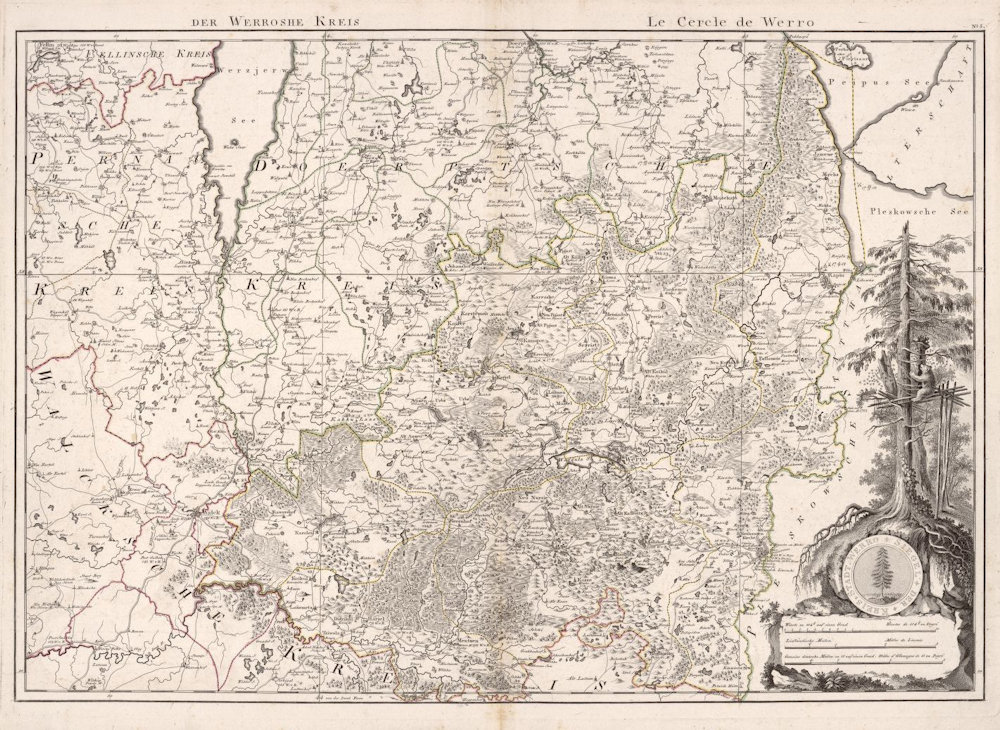

In 2017 Kara Brown used “benign neglect” to describe a stance towards Võro, being neither mandated nor banned in Estonian schools. But often neglect was far from being benign. Given that Võro was ridiculed, not all native speakers were happy users of their heritage language. I think there was time when Võro and other dialects were associated with rural backwardness. Moreover, Võro-speakers were often lumped together by outsiders with their Orthodox neighbours, the Setos, with whom Võro-speakers share their language. The Setos lived outside the Baltic provinces [i.e. of the Russian Empire – Setomaa was part of the Pskov Governorate] and the area where they lived was incorporated into the territory of Estonia with the Tartu Peace Treaty in 1920. After that and until recently (the late 1980s) the Setos were subjected to Estonianisation but also they were see as “the Other”. So you see why Võro-speakers did not and still do not want to be/speak like Setos.

What is your own personal engagement with Võro? In which contexts or places do you speak it, and where would you feel it was not appropriate?

KK: I rarely speak Võro as I do not feel confident (maybe because of hyper-correctness?). Besides, there were no active Võro-speakers in my immediate family, even among adults. After graduation from the Kreisschule in the late 1800s, my maternal great-grandfather became a municipality official. As he was born in Kanepi, which was the one of the centres of the national awakening, he later tried hard to educate (to upper-secondary and university level) all his nine children. I imagine being educated back then meant avoiding dialects and having “language errors” corrected. Another reason is out-migration. My granny left the Võro-speaking area in the late 1920s, and returned only in 1960 after having been imprisoned and deported to Siberia. Nevertheless, I am able to write in Võro and to speak it slowly. I think “receptive (Võro-Estonian) bilingualism” and “new speakerness” are the terms which describe me best.

SI: I am a lecturer and teacher of Võro, and also do linguistic research into Võro, so all this enables and even strongly requires active use of Võro. Actually, in my everyday working life I use Võro more than any other language. I also mostly use Võro with most of my colleagues and friends who speak to me Estonian. So I often speak or write in Võro and will receive answers in Estonian – I am used to doing that and I am mostly quite well understood by these people. They already know and expect me to speak Võro with them. The same kind of bilingual communication happens, for example, between me and Kadri. In everyday communication she uses Estonian, but she does sometimes speak and write in Võro – and her Võro is actually very good.

In the Võro area I deliberately speak only Võro with everyone, except with foreigners who don’t speak Estonian. Outside the Võro area I usually do not speak Võro with strangers who don’t speak Võro to me. However, I speak Võro with most of my Estonian-speaking friends, colleagues and acquaintances outside the Võro area as well. My public speeches are also most often in Võro, wherever in Estonia I am. I have spoken Võro also to the former presidents of Estonia and Finland: [Toomas Hendrik] Ilves and [Tarja] Halonen (quite a good speaker of Estonian). And of course I speak only Võro with my children, wife and relatives – and also with animals, trees and the whole of nature. By the way, speaking with animals and nature, and feeling a sense of unity with them is not weird in Estonia. It is a part of our people’s spirit and traditional culture.

But most Võros are not very confident in their language use, and mostly switch from Võro to Estonian with anyone who they do not expect to actively speak Võro.

What are some examples of words that are entirely different in Võro from the language spoken in other parts of Estonia?

KK: As many Võro words have been incorporated into standard Estonian, people with an interest in languages (literati, teachers) usually know those words. It depends on a person and his/her metalinguistic abilities, but average/common people do not know or use or immediately recall those words – e.g. kesv [“barley”, oder in Estonian], tsirk (“bird”, lind in Estonian), verrev (“red”, punane in Estonian).

Recently, I talked to my university flatmate who was really surprised to find out that “prunts” [a word meaning “skirt”, which shares a root with the Latvian word brunči, and is only in use in southern Estonia]. Despite being from the island of Saaremaa [the Saare dialect is categorised as one of the northern Estonian dialects, but is clearly distinct in intonation from standard Estonian], as a person who knows traditional crafts, she should have known the word. The Võro language area is a contact area where Finnic-speaking tribes met Baltic and Slavic-speaking tribes.

SI: I would add some more examples of totally different words: lämmi [“warm”, soe in Estonian], oigõ [“cool”, jahe in Estonian], pini [“dog”, koer in Estonian], härmävitäi [“spider”, ämblik in Estonian], tsõdsõ [“aunt”, tädi in Estonian], sõsar [“sister”, õde in Estonian], tśura [“boy”, poiss in Estonian], petäi [“pine (tree)”, mänd in Estonian], kõiv [“birch”, kask in Estonian], õkva [“now”, kohe in Estonian], puutri [“computer”, arvuti in Estonian], trükli [“printer” in both English and Estonian].

What kind of media is available in Võro, and is the amount increasing or decreasing?

KK: Some media content and platforms in the Võro language have been funded by the Ministry of Culture’s state programme “South Estonian Language and Culture 2000-2004” and its follow-ups. Uma Leht (‘Our Own Newspaper’), the first and only entirely Võro-language newspaper, has been operating since 2000. UL issues online and print editions every other week. Most copies (9,800 out of 10,300 issues) are distributed free by direct mail. Sixty-five percent of residents of Võru and Põlva counties aged 15+ read or scanned the printed edition of the newspaper and 8% read or scanned the online edition (the survey took place in November 2017-January 2018): this is around 26,500 people (according to Saar Poll, 2018). All seems well with Uma Leht, but in fact most readers are middle-aged or elderly people who are used to following traditional print media. Media behaviour is so fragmented these days: people follow The New York Times and Uma Leht at the same time. It all depends on the content, and local media competition in southeastern Estonia is rather intense.

Since 2005, fifteen Võro-language issues of Estonia’s oldest children’s monthly magazine, Täheke (‘Little Star’) have been published. It is distributed for free to all first-graders as well as to other elementary-level pupils who are studying the language.

In addition to print media, the Estonian Public Broadcasting Service has also transmitted a five-minute Võro-language radio news segment every week since 2005. Between 2005 and 2017, ERR [Eesti Rahvusringhääling

– Estonian Public Broadcasting] also broadcast a number of Võro-language documentary and drama series for television. Võro is also used to a certain extent on social media (on Facebook groups) and Võro-language content is uploaded to YouTube. Volunteers and activists have created a Võro-language Wikipedia version, which includes about 5,500 articles on various topics. This makes it one of the biggest Wikipedia versions among non-state Uralic languages [the only state Uralic languages are Estonian, Finnish and Hungarian].

SI: The main Facebook’s Võro-language group “Võro kiil” has rapidly grown from the beginning of this year and has now about 1700 members. The group gained its rapid popularity growth mostly due to humorous, political, etc. internet memes translated into Võro.

But what Võro badly needs is much more frequent and regular Võro-language media. A five-minute weekly radio news segment is of course too little for a language with about 75,000 speakers. I have said for decades that Võro badly needs daily radio and TV news. Even a five-minute daily news programme would be sufficient to start with. And the newspaper Uma Leht cannot serve as a real news-paper as long as it comes out only twice a month. It should have become at least a weekly newspaper long ago.

Estonian is already a very small language by European standards, with only slightly over a million native speakers. Fears have often been expressed in the past that it could eventually die out, due to influence and domination from larger languages. Does this context make people less receptive to arguments for the support and preservation of an even smaller language, do you think?

KK: There have been some people who have made a zero-sum argument with regard to the case of Võro, i.e. that if more funding, attention and time (e.g. Võro classes in schools) is put into the maintenance of Võro, the position of Estonian will worsen. I do not think this is a serious argument, but when people think rationally/instrumentally they definitely do not see any point in its maintenance as having command of Võro doesn’t increase linguistic reach in comparison with vehicular languages. However, if one wants to transmit relevant meanings to the next generation, Võro should be protected, promoted and taught.

SI: In a globalising and rapidly anglicising world, a very close smaller domestic language can actually serve as a solid support and reinforcement for the Estonian language. Many people understand this.

What are the attitudes held towards Võro speakers in other parts of Estonia? Are there stereotypes or preconceptions?

KK: There has been lot of marketing in recent years; heritage language and culture have become commodified. The language is the most distinctive feature of Võro-speakers or võrokesed (the diminutive form for Võro-resident), otherwise they identify as Estonians, some would call them slightly parochial Estonians who have borrowed from neighbours and share many traditions with Latvians, Russians and Setos, and recently a lot of energy has been invested in “inventing traditions” as I call it. So I believe the image of Võro-speakers has changed from uneducated rural hicks with “language errors” to something positive, authentic and real.

SI: Yes, now many people consider Võros to be the most Estonian of all Estonians. And Võro is often perceived to be an honourable, pure, and ancient language of Estonia – which actually greatly coincides with current knowledge of Finnic historical linguistics according to which, the predecessor of Võro, old South Estonian, is indeed the oldest independent Finnic language. I have heard the opinion that under the pressure of English, Võro will last longer than Estonian.

Estonia takes a fairly protectionist attitude towards the Estonian language, specifying in law when and how the language must be used within Estonia. Given that Võro does not currently hold any legal status and so is not recognised as different from standard Estonian, does this hinder attempts to provide services to Võro-speakers in their native language?

KK: Not really, the language-related laws do not contribute either positive or negative language rights. Some people believe that laws can reverse the language shift, but I do not. Laws together with norms are called institutions, but laws cannot diverge from norms which regard Võro as a home language, as a free-time and entertaining language, but not as a language of astrophysics or ICT (not that there have not been initiatives in this direction). Võro needs serious language innovation (new words for new phenomena) but the timing is bad for the spread of this kind of innovation: as I said before, media behaviour is fragmented, and society is fragmented.

SI: I really don’t believe that anybody has hope that laws would reverse the language shift. But we surely need laws that would clearly and firmly support using Võro, demanding Võro-language education and regular Võro-language media. That would help to reverse the language shift.

As I understand, the language spoken by the Seto people is very similar to Võro, but they do not associate themselves with other Võro-speakers due to religious and cultural differences. How do other forms of South Estonian, such as the Tartu and Mulgimaa dialects, fit into this? Are there significant differences between them?

KK: No, there are not. Language can be easily understood but the difference is in numbers: Võro has more speakers, more activism, more media and is used in writing more often. In common with Seto, it is more peripheral [than the other dialects], that’s why it has preserved its uniqueness. The Mulgi area was better off economically, and it suffered more from Soviet deportations, while the Tartu-based literary language was not used there for writing between the 16th and 19th centuries. Their linguistic and cultural contacts have been slightly different too: in the case of Mulgi with Latvia, and for Võro and Seto with both Russia and Latvia. This is observable in the origin of many personal and place names in southeastern Estonia. Tartu and the Võro area were under the Bishop [of Dorpat, now Tartu], Mulgimaa was ruled by the Livonian Order for a long period.

Later, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth included both former principalities and so did the Livonian governorate (the former Riga governorate minus Smolensk). (In fact, the administrative connections between Estonian and Latvian territories remained until the February Revolution in 1917). Why this early period is important for languages is because it had some impact on mobility and mobility is linked to innovation. The linguistic border between northern and southern Estonian dialects never coincided with administrative borders and it must have had some impact on contacts and variation.

Resulting from the Nordic (or Livonian) crusades, Estonian territories were divided by different rulers (Danes, the Order, the Polish king, the Russian Tsar). Those subsequent administrative borders/restrictions/routines and (institutionalised) serfdom limited free movement and contacts for centuries, and caused further divergence within South Estonian (and North Estonian) speaking areas, too. In the 19th century, at the latest, convergence (Estonian nation and standard building) started. That’s another reason why Estonian varies.

SI: Yes, Mulgi and Tartu have served as a buffer zone between Estonian and Võro. They have protected Võro and Seto from massive influence from Estonian. That is one of the main reasons why they are now themselves heavily influenced and destroyed by Estonian, and are in a much worse state than Võro and Seto.

I’m aware, Sulev, that you’re engaged in developing language technology for Võro. Is this primarily aimed at those wanting to learn the language, or does it have a different purpose? What kind of challenges have you encountered while doing this? And do you feel that technology is more of an opportunity or a threat for smaller languages?

SI: Language technology (LT) is something that every language needs today to survive and develop. The same is with Võro. As Võro is a small language even in comparison with Estonian or Latvian, we have very limited resources for Võro-language technology. That is why we indeed must concentrate in the first hand on the most practical language tools. The first and most important LT resouce and tool is the Võro-Estonian-Võro free online dictionary (synaq.org). In addition to that the Võro Institute together with the Institute of the Estonian Language has created Võro synthetic voices. Together with Tromsø University in Norway we have created a free online environment for learning Võro (Oahpa!/Opiq võro kiilt!). The environment is based on the Võro morphological transducer, a system that enables the automatic analysis and creation of correct grammatical forms in the Võro language. We are constantly improving and developing both the transducer and some practical tools based on it: for example, the Võro spellchecker for Libre Office and the aforementioned learning environment. All these LT tools have been created using such basic Võro digital language resources as language corpora and e-dictionaries.

At the same time we are trying to actively use and maximally integrate all the limited existing possibilities of the Võro LT. For example, Võro synthetic voices are in use both in the online dictionary (one can listen to thousands of example sentences from the dictionary read out loud by synthetic voices) and in the Oahpa learning environment. The voices are also available separately, so you can copy any Võro text (for example an article from a Võro newspaper or from Wikipedia) and listen to it instead of reading it.

In cooperation with the University of Tartu we have also taken the first steps towards the creation of a Võro-Estonian-Võro machine translation system based on the method of neural networks. So yes, as you see, all our LT work is directed towards creating practical and helpful tools for Võro speakers, writers and learners.

So I would say technology is an opportunity for smaller languages, but only as long as it is developed and used for the benefit of these smaller languages, not only for the big ones. Of course, this requires money. Happily we have received some moderate but quite stable and long-lasting support for developing Võro digital language resources and LT from the Estonian National Programme of LT.

What opportunities are there to learn or engage with Võro at the moment?

SI: There are quite a lot learning materials that are usable both by individual learners and language classes or courses. These include, for example, schoolbooks for children, such as ABC books, readers, books about local history, picture dictionaries, workbooks etc. Then the aforementioned dictionaries both in printed and free online mode and an online learning environment. Also, the Võro edition of Wikipedia is usable and has been used for language learning – both by reading and writing the articles. Unfortunately, the Estonian education system and language policy does not clearly, actively and sufficiently support learning Võro or its use as a language of instruction in schools and in preschool education. Despite this, around half of all Võro-area schools and kindergartens offer some classes in Võro. In schools it is usually only one lesson a week and not for all classes. In kindergartens it is only one day a week – the so-called “language nest day”, when the teachers speak only Võro with the children. Teaching Võro both in schools and kindergartens is supported by the Võro Institute. Whether or not Võro is taught in a particular school or kindergarten depends mainly on the will and enthusiasm of the leaders and staff.

There are also some regular courses in Võro both for beginners and for advanced students at the University of Tartu. Every one or two years a Võro course takes place at the University of Helsinki in Finland or at some other foreign university. Võro courses for adult learners organised by Võro Institute regularly take place in Võru and sometimes also in other places in the Võro area. I am a Võro lecturer and teacher myself at both the University of Tartu and the Võro Institute.

Do you feel optimistic about the future for the Võro language, or do you think it will continue to lose ground to standard Estonian?

KK: As me and Kara Brown wrote in the Regional Dossier: “with steps forward and steps back, the contours of the next decade of Võro-language learning are difficult to predict”. It means that there are many positive changes (popular interest, increased prestige, etc.) but also negative (it is not used with children). There are a couple of families – tens of them, in fact – who speak Võro to their children, but most people do not.

SI: The future of the language clearly depends on the language users. If they used the language in their everyday life with children, with their families and with other people, and if they actively demanded from the state, local community and school system more rights for Võro and more frequent and regular use of Võro in the education, media etc., then Võro would have quite good chances of surviving and of winning back the ground it has lost to Estonian. Unfortunately, most Võros are currently quite passive both in using their own language and in demanding more support to Võro. So, in order to save the language, we need quite radical changes in attitudes and behaviour among Võros. I think these changes are possible and they are already happening, but very slowly. We have to get these changes to happen much faster. In principle, revitalisation of a language is possible even after its death, as we have seen in the cases of Cornish and Hebrew. But with every lost decade the prospect of revitalisation becomes less hopeful and less natural, and much harder and more expensive. So we really should hurry to do much more to support our language.

You can find out more about Võro on the website of the Võro Institute

© Deep Baltic 2019. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.