by Paulius Tautvydas Laurinaitis

Much can be learned about a period in history by its views of the future. Whether plagued by pessimism or infused with an all-encompassing optimism, forecasts of the future reflect present-day concerns. Press reports published at the time provide one of the more interesting sources of insight into the prevailing popular mood. Inter-war Kaunas, where newspapers, magazines and radio programmes were the main means of disseminating information, was no exception in this regard.

In many ways, 1933 was a memorable year for architecture: the newly installed, Nazi-led government in Germany closed the Bauhaus school and the fourth International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM, by its French acronym) heralded not only a coming watershed in global urbanism, but also the demise of optimistic constructivist ideals in the Soviet empire. On the other side of the Atlantic, movie screens showed King Kong climbing the world’s tallest skyscraper, a structure that had come to symbolise emergence from the Great Depression. What kind of future was being predicted for Lithuania’s provisional capital in those turbulent years?

A publication released by the Department of Municipalities presented a vision of Kaunas in 2018, exactly one hundred years after the declaration of Lithuania’s independence, that imagined a city which had continue to develop in keeping with key modernist concepts of technology and hygiene. In this futuristic vision, cars on streets were replaced by automated capsules transporting passengers from point to point. Consumers would never have to leave home, selecting their purchases from catalogues instead, with every purchase registered automatically by dictating a product code into one’s telephone. The work day would shrink to a quarter of its current length, leaving time for citizens to enjoy life in a true garden city, where everyone had their own piece of land, complete with gardens and swimming pools, covered in winter by a glass dome. The all-important recreational dimension in the Kaunas of the future would thrive on the banks of the river Nemunas, refurbished in modern style. Palm trees and tropical flowers would grow along riverbanks lined with marble bricks reflecting the colour of the sky, turning the Nemunas into a ribbon of blue water flowing over a riverbed of golden sand, carrying along crowds of people in small boats.1

An equally impressive vision, inspired by the praise showered on a modernising Kaunas by the mayor of Tallinn, appeared in the local press in 1934. The Kaunas of 1984, though no longer the capital of Lithuania, would become an important industrial centre, where workers lived in convenient suburbs and the once chaotically built-up sections of the city had evolved into lush neighbourhoods of multi-storey buildings. Laisvės Alėja was no longer just the main avenue in Kaunas, but the principal boulevard of the entire country, with the highest ‘skyscraper’ in 1934, the Pienocentras building, now dwarfed by an entire city centre full of multi-storey structures. Unarmed public safety officers would be assisted by anthropomorphic robots regulating traffic at each intersection, while tourists arriving by airplane ‘from as far away as the Philippines and the Hawaiian Islands’ would be greeted by a two hundred-metre-tall tower built in memory of the trans-Atlantic pilots Darius and Girėnas: ‘In the evening, when dusk falls over Kaunas, their colossal bronze heads are illuminated with powerful spotlights. From here, one can see all of Kaunas.’2

In truth, not every vision of the future Kaunas was optimistic: dystopian narratives were often used to criticise the shortcomings of the day. The country’s official government newspaper, Lietuvos aidas, published an anti-utopian story about a busload of tourists visiting Kaunas toward the end of the third millennium. The visitors reach one of the more popular observation points in the city, only to see a rather bleak image of the provisional capital: church steeples, the main accents on the city’s horizon, were crumbling and overgrown with moss, surrounded by bush-covered ruins. Interestingly, this depiction included recently completed government structures, such as the Hall of Justice and the Bank of Lithuania, among the disintegrating buildings.3 The hypothetical historians of the future depicted in the portrayal mention 1932 as the year of the city’s downfall – the same year that the article was published. A foreign army entering the city in 1942 (a rather prophetic prediction) finds it completely deserted. But the imagined scientists of the future are completely unable to answer one basic question: what compelled everyone to emigrate from the city? The author of the article provides his own sarcastic answer: annoying charitable lottery ticket sellers and donation collectors in the city streets had forced everyone in Kaunas to flee to more peaceful countries.

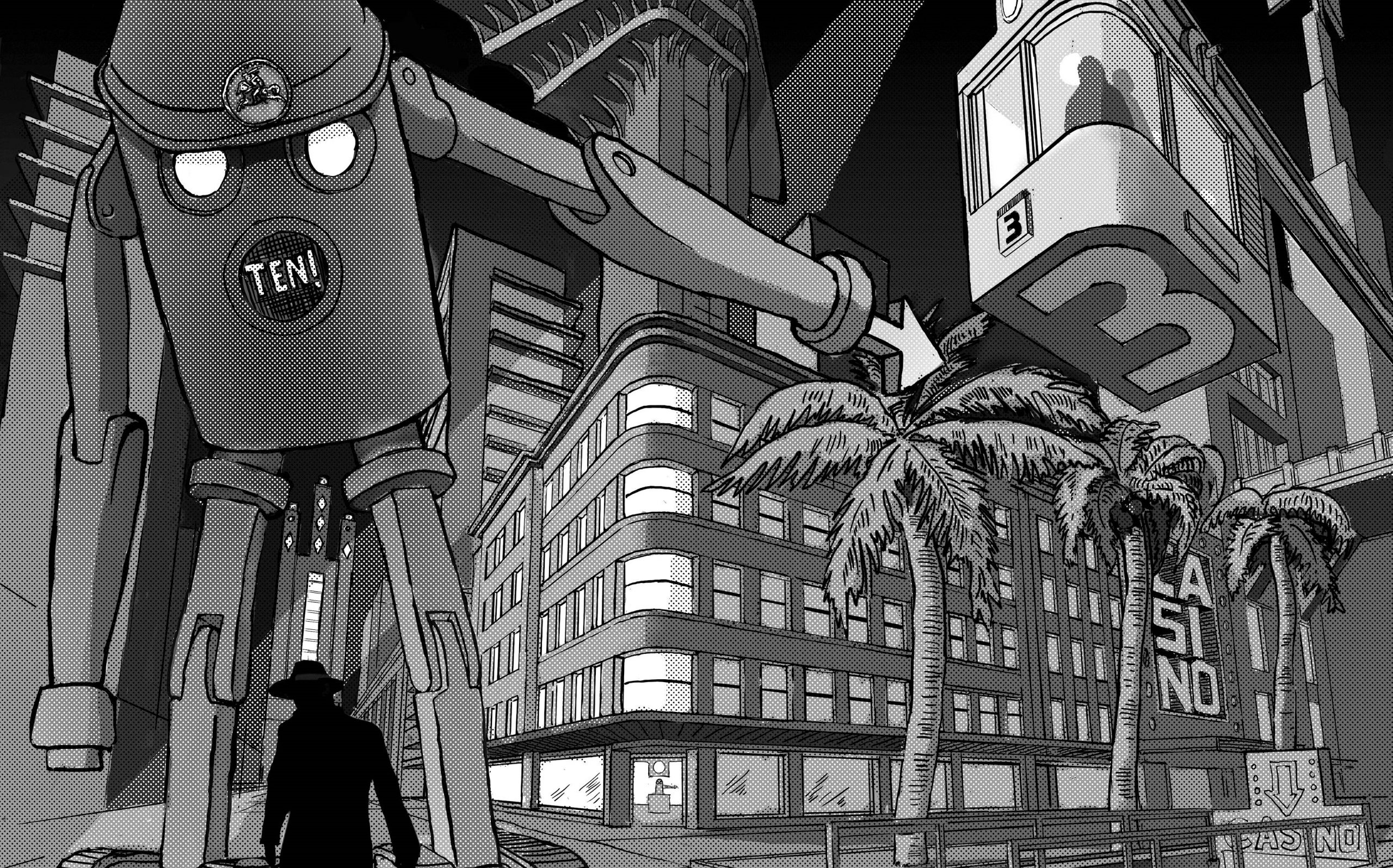

An equally bleak vision of a technologically advanced but dystopian city appeared in the same newspaper in 1934. In the pacifist and alcohol-free world of the year 2000, where gambling had been outlawed, Kaunas remained the only enclave with legalised gambling, which eventually led to its demise. Some sixty thousand gambling-obsessed people live in a decaying city, doing the same thing every day: ‘Even though transportation is so inexpensive and convenient nowadays, with radio cars and airplanes, no one uses them. They save every cent they have for the clubs. And those who’ve lost everything sit at home in front of the television mirror and watch what’s happening in the clubs.’4

The vibrant 1930s era of jazz, technology and aerodynamics was symbolised by skyscrapers built with modern materials such as glass, steel and concrete. In 1931, for example, one of Lithuania’s largest dailies, Lietuvos žinios, portrayed the Empire State Building in New York as an example of how homes of the future will rise ever higher, and as proof that buildings of the future, like automobiles, trains and airplanes, will be made solely of metal. ‘No one even thinks of making ship hulls out of brick,’ journalists of the day wrote, making their argument for metal-based architecture.5 They also envisioned that, given the demand for a regular and uniform supply of light, such metal buildings, like all factories in the future, would be completely devoid of windows. Moreover, all offices and services that residents might require would be housed in one skyscraper, complete with a solarium, shops, restaurants and a theatre. Although idealised depictions of skyscrapers predominated in the inter-war Lithuanian press, the Kaunas City Council banned the unauthorised construction of buildings higher than six floors in the late 1930s, reserving this privilege for only the most important landmark buildings of the future.

The skyscraper concept was also once considered as a means for the now predominantly Lithuanian Kaunas to address the problem of its Tsarist-era architectural legacy. In one vision for the future, the much-criticised Russian Garrison Orthodox Church (popularly known as the Soboras) at one end of Laisvės Alėja was to be replaced by an eleven-storey national ‘landmark’ to house ‘the rarest of academic books and works by famous Lithuanian authors […] as well as all of the Lithuanian nation’s cultural treasures,’ and would include ‘Lithuania’s largest library, reading rooms, and radio and television equipment.’6

Émigrés returning for a brief stay in Lithuania also generously shared their own future visions of the inter-war capital city. Noticing the increasing number of modern urban features in Kaunas, one Lithuanian-American wrote a letter to Lietuvos aidas, sketching out a future Kaunas full of classical architectural forms: ‘Laisvės Alėja […] will be lined with monuments or other simple ornamental objects. Entrances to the central pathway along Laisvės Alėja will be covered with attractive and wonderful gates or arches dreamed up by architects,’ and, according to the letter’s author, the gardens around the War Museum and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier will be covered by a ‘magnificent, grand arch’, protecting the national pantheon, then still under development, from the rain and transforming it into a true ‘Altar of the Nation’.7

These playful, optimistic and sometimes ironic visions of Kaunas’ future reflected the prevailing concerns of the era: not only urban planning obstacles, but also social ills or such symbolically significant current events as the death of two trans-Atlantic pilots. Fantasies about the city’s skyward expansion were expressions of the desire to transform a city centre still dominated by one and two-storey buildings into something resembling a large European city. The vision of Kaunas in 2018 included a museum exhibiting ‘the remnants of demolished shacks’ – a direct reflection of the nationwide Lithuanian campaign of the 1930s to rid the country of shoddy construction. Similarly, the optimistic view of a city focused on hygiene and technology was a direct expression of the modernist era: urban planning discussions regularly included consideration of the ‘garden-city’ concept, still very popular at the time. In some instances, ideas about a utopian garden city of the future found their way into administrative and institutional debates, not just into slightly whimsical press articles: a surviving account published in a newspaper in 1938 outlined one resident’s proposal to plant gardens on every rooftop along Laisvės Alėja.8 Sometimes, the problems of the day were reflected in more amusing ways: a photomontage published as a joke on April Fool’s Day in 1931 showed an image of a cable car, a clearly utopian idea for Kaunas of that time, to highlight both the opening of the first (and much more modest) funicular railway in Kaunas and the increasingly acute problem of transportation links between the city’s upper and lower districts.9

1. Ignas Rašimas, Šimtametis Kauno jubiliejus [Kaunas’ Centenary Celebration], Savivaldybė, 1933, nr. 11, p. 7–17.

2. Edmundas Dantas, Kaunas po 50 metų [Kaunas in 50 Years], Diena, 1934 08 23.

3. Pivoša, Taip Žuvo Kaunas [This Is How Kaunas Died], Lietuvos aidas, 1932 06 18.

4. Eikis Nartakas, Lietuvos aidas, Kaunas 2000 metais [Kaunas in the Year 2000], 1934 02 21.

5. Ateities trobesiai [Homes of the Future], Lietuvos žinios, 1931 02 26.

6. Ignas Rašimas, Šimtametis Kauno jubiliejus [Kaunas’ Centenary Celebration], Savivaldybė, 1933, nr. 11, p. 7–17.

7. Kazys S. Karpius, Kaip amerikietis lietuvis vaizduojasi Kauną ateityje [How a Lithuanian-American Imagines the Kaunas of the Future], Lietuvos aidas, 1935 09 18.

8. Siūlo Laisvės al. stogus apželdinti sodais [A Proposal to Plant Gardens on the Roofs Along Laisvės Alėja], Laikas, 1938 08 08.

9. Karikatūra [Caricature], Dienos naujienos, 1931 04 01.

This article originally appeared in the book Architecture of Optimism: the Kaunas Phenomenon 1919-1940. Republished with permission.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.