As detailed in Deep Baltic’s interview last week with the Lithuanian author Alvydas Šlepikas, in recent years the stories of the so-called “wolf children” have gained more attention, in Lithuania and elsewhere. The wolf children found their way to Lithuania in search of food or were left behind by their families following the arrival of the Red Army in 1945 in the region of East Prussia, a historically mostly German-populated region alongside the Baltic Sea (it is now the Kaliningrad oblast of the Russian Federation).

Having had to survive in the wild, many of the wolf children, who numbered several thousand, were adopted by Lithuanian families and given new names and identities. In Soviet-occupied Lithuania, discussing their past was considered unwise or actively dangerous, and only in recent years have journalists and artists begun to look into the subject, with Šlepikas’s novel In the Shadow of Wolves being an acclaimed example.

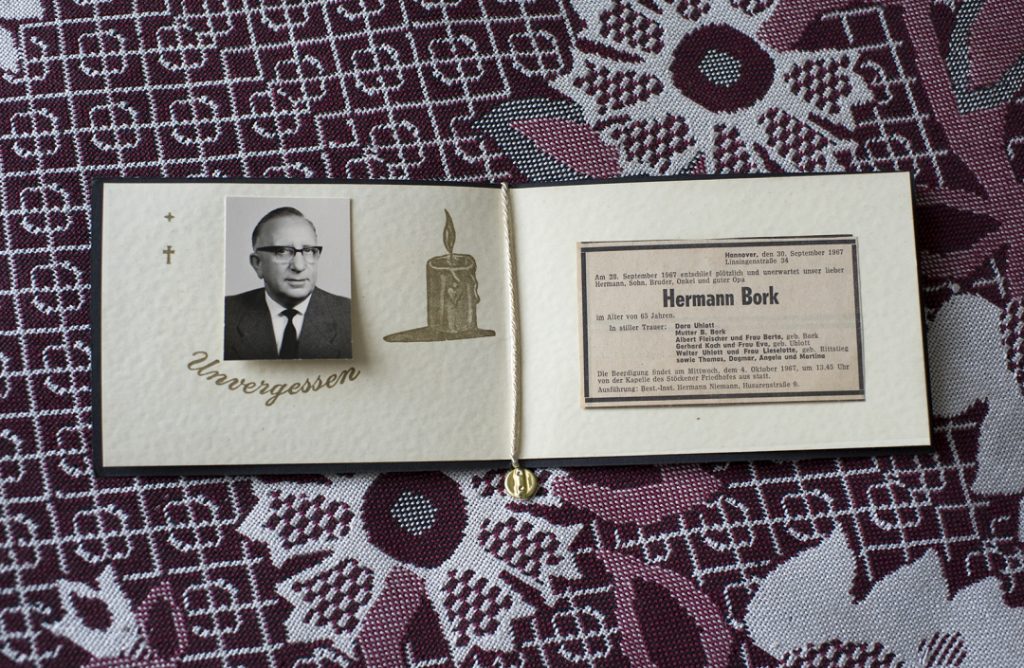

The Dutch photographer Claudia Heinermann’s book Wolfskinder A Post-War Story, originally published in 2015, has been among the most prominent examples of the growing interest in the topic. Her pictures give an insight into the experiences of people who survived war, incredible privations and sometimes hostile reactions from local people and authorities.

She tells Deep Baltic that her interest in the subject began in 2011, when she came across the book Wolfkind by Ingeborg Jacobs, which tells the story of one of the wolf children. She began researching the subject the same day, and says that she has been gripped by it since then. Arriving in Vilnius four months later, she decided to collaborate with journalist Sonya Winterberg in order to preserve the stories of as many of the wolf children as possible.

“Around 70 wolf children were left in Lithuania at that time, most of whom were well-advanced in years. Over the years, we visited 42 of them over the course of a number of trips, and many of them have become very dear to us”.

In Heinermann’s book, pictures of the surviving, now-elderly wolf children are interspersed with images of their homes, archive photos and images of the forests, rivers and fields of Lithuania.

“In the collective narrative and memory of the wolf children, nature plays a major role, and I wanted to bring the viewer into those landscapes.”

As she relates, Heinermann’s visits to Lithuania while researching the project were often emotional, due to the harrowing stories shared by the remaining wolf children. “Their stories are heartbreaking, and it was often really hard to imagine how they survived”. She remembers one trip in which all of the handful of people interviewed described watching their mothers die of starvation.

The following story is from Bernhard Keusling (Bernardas Kizlingas, as he was known in Lithuania), born in 1937 in Gerdauen, East Prussia (now Zheleznodorozhny, Kaliningrad oblast):

Mother started to work as a day laborer on the fields in exchange for food, but the hardship put a toll on her health. Soon she was too weak to work and fell ill. She had always given us all she had so that we didn’t have to suffer too much from starvation, but in the end she paid the price for it with her own life. She died in front of our eyes from starvation. I was at a total loss and had no idea what to do next. My little sister cried inconsolably and lay next to our dead mother for days – until she herself passed away…

There was nothing I could do, but cover them with a blanket and leave. I was eight years old and on my own now. I joined some other children on my quest for food and would eat anything to stay alive. One day we found a dead horse from which we cut chunks of meat. On occasions we would even live on fodder or leaves we picked off trees. I had heard about Lithuania every now and then and the abundance of food there. So I made my way there.”

Heinermann also highlights the parallels with more recent examples of forced migration. “It’s a historical topic but at the same time very universal. Unfortunately stories like theirs repeat themselves over and over again”.

“In 2017 there was a shocking appeal from various aid organisations, who said that 10,000 children who had reached Europe had disappeared without a trace in the middle of the refugee crisis – 10,000 children. Can you imagine the dangers these children are exposed to today?”

Heinermann’s previous projects include work on Rwanda and Bosnia, but her most recent undertakings demonstrate a continuing preoccupation with the Baltic countries. She tells us that since 2016 she has been working on a trilogy on the subject of the deportations from the Baltics during their occupation by the Soviet Union, of which the first part has already been published. “Eyewitnesses tell about the occupation of their homelands, the resistance movement, deportations to remote areas, imprisonment in gulag camps and what happened to them after their release. I have travelled to the places they speak about in Siberia and Kazakhstan”.

“Right now I am working on crowdfunding for the next part, which is based on the story of one Estonian eyewitness. That led me to a nuclear test site in Kazakhstan and the beginning of the Cold War”.

All images credit – Claudia Heinermann

You can find out more about Claudia Heinermann’s photographic work on her website

© Deep Baltic 2022. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.