by Laurynas Katkus, VILNIUS

I

what I remember: green lamps, green torchere shades by the bed spreading a soft light, falling on pale wood furniture; that’s why I remember—pale, smooth, imported, never seen in the apartments, hospitals, or vacation cottages I had slept in previous to this day, this trip; to lie in a strange in-between space and think about the polished elevator that raised us from the hall covered in soft carpets to our room, or about the train, whose attendants were young and whose windows weren’t covered in a layer of dirt; they were even decorated with colorful little curtains, particularly in the dining car, where my father, not traveling this route for the first time, took me, and with an experienced traveler’s certainty ordered me an omelet on a metal plate or something like—still in Lithuanian, although the Lithuanian language was already mixing with harder, more commanding tones, weakening and retreating, until it would finally dissolve in the early morning air of the giant Minsk station, remaining only in a few lockers—our heads, shoving our way through the crowd—but that would be later, now it was evening, the lights were already being turned off, the green lamps were off, the compartment lamps were off, only the ceiling lamps shone wanly; you pull the adijalas1—the blanket—with the folded sheet up to your chin, but sleep won’t come anyway, excitement seizes you, hearing steps in the hallway, the elevator rattling (its shaft is right next to the room), the wheels rocking on the rails—

and how could it be otherwise; this isn’t just any old train—it’s the most important, its name no less than “Lietuva,” traveling to the country’s capital; it is, after all, our representative, obliged to show the wide world who we are (postoyannoyu predatel’stvo—in a constant state of repressentation, as Father says), which gathers in all of our province’s clients with business at the central institutions, with petitions for “our folks,” and the higher dignitaries shoving through the crowd next to the city’s gates with Suvalkian ham and bottles of brandy;

lamps, green lamps, why do I remember that in particular, why just the small details, exhibited like prehistoric amulets in memory’s display case, why haven’t the streets, the paintings, the cafeterias, the sky survived? I only remember some kind of lower level coatroom where I waited for Father with my brother, and the elegant elderly coatroom clerk asked what we’d seen in Moscow so far and advised visiting the Lenin Mausoleum—it’s worth it, it is (we never saw it, although we tried—the line was too long), and then Mother’s face on the other side of the glass, Mother, whom we’d never before been separated from for such a long time, with four striped plastic sacks stuffed with objects for our comfort and joy, Mother, dragging bags of rock from fairytale land to this vale of tears, oh, the proficiency of Soviet logistics, the heights it had reached, so Mother’s in Sheremetyevo Airport, but that’s all

[space]

through the bedroom window, between the bushes, I see the point of a budenovka hat2, then a plastic sword—it’s Pashka, the neighbor’s kid from the third floor cavorting through the bushes wearing a funny hat with a red star, excited, of course—reincarnated into an Uncatchable, shouting “vperёd, krasnaya gvardiya—forward, Red Guards!,” he’s Budyonny and Chapayev at the same time, until his father or mother call him home with this half-scream, half-grunt that a passerby, upon hearing it, thinks someone’s met their demise; his parents are deaf, though they’re Russians otherwise, deaf Russians—it happens too—and Pashka plays without friends now, even though earlier, when we still sat in the sand box, up to about five, when language wasn’t important yet, I would play with him, exchange toy cars, we’ve shove each other around

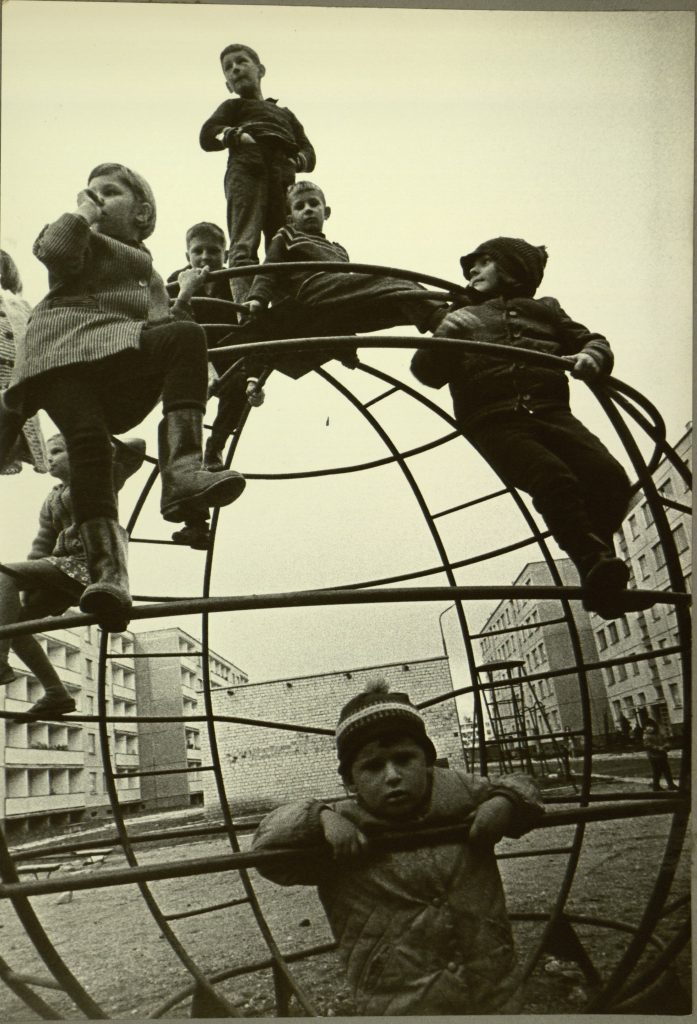

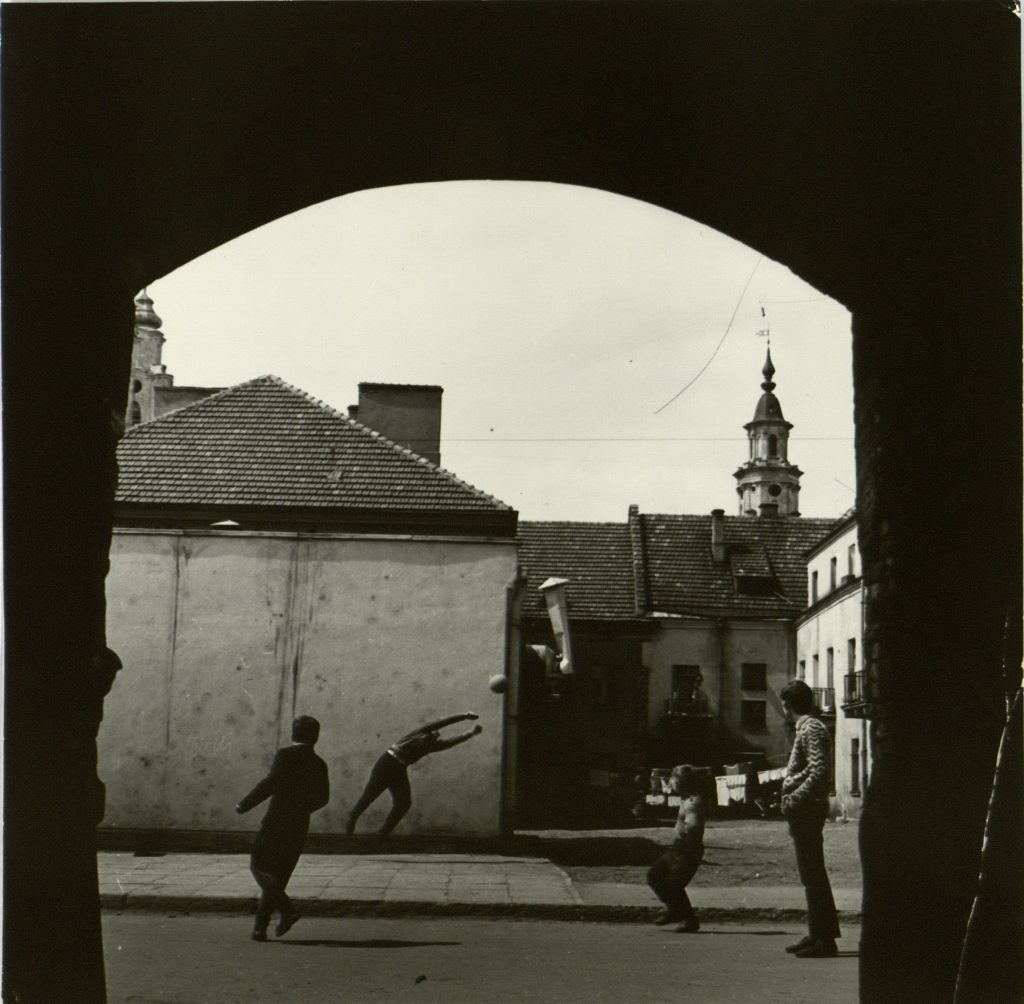

but now Pashka is as alone as a revolution in the desert, he’ll have to wait until another little Russian grows up, what’s his name, from the first pod”yezd—entrance, since the Russian Civil War was foreign to us, although of course we’ve seen the movies; we play the classics Cops and Robbers, and Little Arrows, and Ali Baba, but not a civil war, not that

maybe not yet? because when we took up “historical” games, they were rather peculiar, in the eighth decade in a Vilnius courtyard we played Teutonic Knights who fought not with the Lithuanians or Prussians, like you might think, but with the Russians; it’s not surprising—the machine for destroying the last remains of bourgeois nationalist prejudices was working non-stop; after all, I would buy colorful little books about the Soviet partisans’ heroic deeds and curly-haired Lenin, who never lied to his parents—I’d buy them at the Šatrijos bookstore myself, without any coercion, after all, I’d go to movies about the war, I’d read Ostrovsky and Gaidar, and I used to swallow it all, everything was chotka—cool—and next to that I had learned, practically by rote, Daugirdaitė-Sruogienė’s textbook on Lithuania’s history, and I colored the farthest extent of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s domains in pencil on a map of the USSR, in spots unintentionally capturing even more, including Moscow—

oh, these Teutonic knights and these Russians, they’re worth remembering; our apartment building was mostly Lithuanian, and the leader of the kids was this Raima, but Russians dominated the neighboring courtyard—or maybe it seemed that way to us because it wasn’t ours? One way or another, its verkh—leader—was a non-Lithuania by the name of Baryga; at the time his name seemed strange and powerful, so I was surprised when I recently found out that it means, roughly, petty thief, so one way or another, no one in the yard called him Šaša or Mitia, just Baryga, that’s all; his appearance didn’t leave his name behind—Baryga was a stocky teenager with long arms, a short neck and a small round head, the kind you couldn’t expect anything good from, but in his case the exterior was deceptive: however strange it may seem, Baryga and Raima were friends, and it wasn’t just that they didn’t fight among themselves, not just that they wouldn’t touch members of the opposite commandos, but that they thought up all sorts of amusements together; at one time, to keep up relations they stretched a “presidential telephone line” made of wire and tin cans between their two facing windows, which raised a considerable stir in the courtyard since the sound supposedly traveled it so well it was possible to speak in a whisper,

and those medieval battles thought up as amusement; Baryga probably thought up the idea since he’d seen “Alexander Nevsky” but not the movie “Herkus Mantas” about the Lithuanians fighting the Germans, while Raima diplomatically agreed, agreed to be the Russians’ enemy, so we, the Lithuanian courtyard, became the Teutonic Knights, we represented the West, still some sort of acknowledgement; we began readying ourselves, looking around for wooden swords, rummaging through storage sheds on the short winter afternoons, searching for strong plywood suitable for shields, we fastened handles and drew crosses, my cousin probably helped me since I wouldn’t have managed to draw such a straight, superb black cross on a light background by myself; Raima looked around for a leader’s insignia, a giant shield with three crowns above a cross, once, going to the window, he showed it to us—it was stunning; the days shortened, the tension grew, rumors made the rounds, until at last the news flew around the courtyard: tomorrow evening! tomorrow we’ll go to battle in a remote courtyard; during the night it snowed cheerily, the time went by terribly slow, but there, finally, one after the other, heavily-armed knights of the Order began stumbling out of the five-story stairway, the Grand Master Raima came out, too, made a short military survey; there were a few missing, parents who had heard something decided not to let them out, but the majority were fully prepared for war, we marched forward to the site of the battle, we moved slowly, our stiff legs stuck in the dirty snow, in the strangely deep drifts; in the dark, the space of the courtyard spread and got bigger, the walk to the corner courtyard took half an age and beyond it we saw dark shadows slowly creeping from the other side—

it was them! The enemy’s army! We stopped opposite one another, our leader went forward, Baryga did the same, a discussion ensued about how we would fight, Baryga’s shield was huge, too, from head to toe (and what was drawn on it? Surely not a star, nor a hammer and sickle; maybe a sun?); the suggestion to fight all against all was rejected because of the bardakas—the chaos—and the possibility of injury, with a bit more discussion it was decided the leaders would fight, standing in for their armies, so it would be a duel, and Raima with Baryga took up their battle poses, started waving their weapons, Baryga swung a wooden bludgeon above his head, crossed with the Teutonic sword, smashed into each other’s shields, which cracked but held, the warriors changed positions, the old ones left gaping in the snow—

here the enthusiasm began to wane, as it became clear a win wasn’t very probable, to be reached only by beating the opponent to a pulp, and somehow that wasn’t very attractive, and in general, the heat of battle was shoved aside by thoughts of peace, for example, about a nightcap of hot milk in the kitchen, about a soft bed, and the duelists’ movements started slowing, wandering, until in the end both of them, breathing hard, lowered their weapons, stood there glancing at one another, and then Raima raised his hands with the shield and the longsword to the sky, like Vytautas in Matejko’s Battle of Grunwald, and announced the battle had ended evenly tied, and ordered his army to disperse

afterwards for a few months anyone wandering into the courtyard had to imagine some religious sect had moved in there, since plywood rectangles with black crosses lay about everywhere, out of boredom broken up some afternoon, in the end the bending and stomping did in my small shield with my cousin’s gouache work

[space]

the Russians had the upper hand not just in our battles, but in another important sphere as well—vocabulary; first of all came the swear words: mat appeared on my lips before I knew what it meant, I didn’t need to wait for trade school or the army; (on the other hand, in our circle it never did become an everyday thing, something restrained us—fear of adults? shame?; only a few cursed freely, for example, Mukas from building 144, nicknamed that way because of his short, nearly Lilliputian height, who perhaps was the only one in the yard who didn’t have basketkės—sneakers—and played football in torn sandals; superbly, by the way—Mukas, who spent as much time in the juvenile home for hooliganism and theft as he did at home); however, the Russian language was an inexhaustible source of sayings, without which you wouldn’t be accepted in the yard; somehow, quite naturally, without doing anything or skirmishing with anyone, someone who spoke properly would be viewed as a slabakas—a weakling, and who wanted to be that; the law typical of every language of the young was at work—it must be your own code which, when used, spins an aura of otherness and exoticism, allows separating your friends from the weirdos (nows this youthful snobbery is supplied everywhere by MTV English)

all the more since innocent Lithuanian cuss words, those “go to the devil,” or “toad,” those slow-footed provincial comparisons, were distant from the city’s reality, literary exclamations couldn’t compete with the laconic, naked, brutal Russian word, and I wasn’t the only one who thought so (once, maybe at six, I even consulted with my mother about what to replace davay—c’mon—with; there were no suitable alternatives)—all of my fellows spoke a mix of both languages, putting Lithuanian inflections on Russian words, translating phrases word for word, but what do you want, the Russian language was everywhere, in the movies and on television, in the offices, streets and school, and whoever lived in the city grew up in nearly bilingual surroundings, learning them in small groups from first grade on—as the Party had ordered at the first Tashkent conference in 1975—and from the pleasant teacher Anisimova, who ordered us to write up an entire row of spiders—the letter ж,—and scattered your attention with garish makeup and shaved eyebrows in a wide face

[space]

but all the same there was something wrong with them, those Budenovkas, those white schoolgirl’s aprons, the steel teeth of reserve officers; they were different and felt this themselves, and middle-aged women, officers’ wives, raised hell in the food stores when they couldn’t get Kostroma cheese or Moscow dumplings or other food products with Russian names manufactured in the Lithuanian SSR; they’d shriek in a threatening siren voice, developed that way through long years of battles for existence, compelling the dumbfounded to stop dead in their tracks—Ya veteran otechestvennoy voiny, kak vy smeyete! “I’m a veteran of the Patriotic War, how dare you!” or Ya pozhilaya zhenshchina, kak vy… Govorite na chelovecheskom yazyke! “I’m an old woman, how dare you… Speak in a human language!”—this expressive outpouring of theirs came from a feeling of uncertainty, of estrangement;

this was felt particularly strongly at the beginning of adolescence, national boundaries became obvious, practically impassable—I vaguely remember once as a teenager I went to the field beyond the nine-story apartment building to play football with the Russian kids, and we fought furiously, but peacefully, though later, discussing the results next to the newly-built nine-story building, standing around on the concrete plaza with rails for rolling out the garbage containers, Arvydukas, if I remember right, said the Russians are katsap3; and you’d hear more and more stories about attempts to take money or something else, about fights, and when you had to go past those katsap’s school, through their yards where, cracking semechki—sunflower seeds—on the benches, several pairs of well-peeled eyes stared at you (no one I knew, since Baryga had disappeared somewhere), a harrowing tension would form—mostly because they, probably giving way to us in terms of numbers, were unusually good at organizing, at assembling into a shayka—a gang—and from morning until night, everywhere, wherever you went, whatever you did, you never saw them alone, it seemed they ate and slept together too

men’s gangs, this form of society, extending at least to the mir, the world of a Russian village or maybe to the Iron Age, came to mind again a few years ago in a German city, waiting for a bus; suddenly, out of nowhere, the empty station was occupied by a company of young Russians who were jumping out of their skins, screaming, cursing, and telling stories without lowering their voices, convinced that no one understood them: how terribly drunk they’d gotten before going into the army and vomited all over in the commissariat, how in Paris one paid for a peep-show box and three of them got in there, and so forth, and so on, and giggled laughed hee-hawed, constantly looking around to see if someone noticed how kruto, how cool, they were, looking me over particularly carefully; I guarantee if they had known I understood Russian they would have spoken to me, the gang’s representative would have come closer and, pretending to be friendly, asked what I was doing, where I was going, and all the rest of them would have stood around casually, like there was nothing going on, while they were actually listening carefully to my answers and deciding if was worth jumping me; the Russians have developed gang behavior and rituals to perfection; other nationalities aren’t exactly doves of peace, but can’t equal them in this respect

in adolescence, which corresponded to perestroika and the Sąjūdis movement4, national and all the other tensions suppressed by the government rose to the surface at the time perestroika was still only happening on the television screen—that is, in Moscow—the conflicts between the pankai and montanos,5 the Lithuanian and Russian youth, that proliferated in 1980s Vilnius was a sign that the social mash had begun to sour there, too; and when we, beginners, the still uninitiated pankai, discussed the latest fight in Kalnai park or next to the Bizonai valley, the rumors frequently reported the victory was not on our side; the reason for the loss was held to be due to an unexpected attack, numerical advantage, or the pankai’s poor weapons (really, what could the pankai’s piano strings do against the montanos chains? however, the pankai couldn’t adapt the latter for reasons of style); in a word, the mood wasn’t the greatest, help was expected only from the new neighborhoods, the Karoliniškės or Lazdynai

buddies, who, according to legend, were particularly fierce and powerful, I remember that even our hard-boiled shop instructor Mazolis, who would guard the front door at school during the disco dances and do the “face exam,” once, going out for a smoke in the yard after dark, got clobbered by a company of montanos prowling about like cats around bacon, then the militsiya6 came to the school, a rare occasion

II

[Когда лжешь] легкость в мыслях необыкновенная

Гоголь, Ревизор

KHLESTAKOV [confabulating] I am extraordinarily light of thought.

Gogol, The Inspector-General

The end of the 1980s; evening. When he comes, the television is turned on in our house. Evening is a time of nerves, a space of nerves—the cage of the screen, the watching eyes: my eyes, the family’s eyes, Lithuanians’ (three million, as it’s sung in the song) eyes.

At first, as it should be, the tension is within the limits of the norm—they’re showing our news program Panorama; they have all kinds of reports about what’s going on in the Republic, different lexicons mix in it, next to “perestroika” and “sovereignty” there’s also “extremists” and “nationalism,” our stagnatories aren’t sitting on their hands, but to tell the truth, they’re not causing much tension, they’re retreating on all fronts, they’re locals and will be overcome sooner or later; after Panorama there’s a break—cartoons for the kids, then you can visit the refrigerator, the toilet, and the sink. At exactly nine, a shrill trumpet sounds, and we know we need to rush back because this evening’s main feature has begun. The red walls of the Kremlin and towers with stars alternate in the announcer’s studio, in the ether, informatsionnaya programma „Vremya“—the news program “Time,”—segodnya v vypuske—in today’s news…It lasts about a half hour, first the report on the work of the General Secretary and the Central Committee; from this coded text, from particular places, word order, and what’s mentioned or not mentioned, you can guess which way the wind is blowing at the Kremlin today; then a variety of other news, among them, and lately more and more often, from the Pribaltika, the Baltics. Here the tension reaches its peak: what will they show? Will they again scold the irresponsible nationalistic elements raising their voices in our Republic and explain how closely our people’s economies are related? Will they talk to our stagnatories? Or maybe, impossible, they’ll mention Sąjūdis? No, it’s the same thing again. The reporters talk to the eighty-year-old folk writer B., who, in severe language, condemns the irresponsible nationalistic elements encouraged by imperialistic secret services; or, let’s say, they announce the people’s obvious support for an initiative by the Great Fatherland’s war veterans (the screen shows a crowd next to the Lenin monument, children and young people, a serious, intense woman’s face, filmed a few years before). Frustration seeps into the arms and legs, and the room charges with negative energy. Come on, that’s not true, the people held a rally today because of something completely different and in a different place! How can they do that! In this moment, together with three million others, you curse the announcers, reporters, and the entire Central Television.

Lozh, pizdёzh i provokatsiya—lies, nonsense, and provocation, Father would repeat after a report like that, and actually, that was the first time I experienced what propaganda is, how cleverly anything, the most obvious thing, can be silenced, changed, distorted, turned upside down. You need facts, they appear easily, like out of a wizard’s hat, one, two, and shazam! Unnecessary details vanish without resistance… and this all goes on, not once, but day after day, hammering into the heads of the wide Fatherland’s viewers what unrepentant fascist animals lurk in the Pribaltika, how they disturb the peaceful Soviet life. Fantastic, in all senses of the word, productions—you could say masterpieces— of this type appeared after the storming of the Lithuanian parliament building on January 13, 1991. I have Alexander Nevzorov’s film Nashi7 in mind.

Without a doubt there were other conscientious programs and journalists on Moscow television—including the announcer who refused to read the regular disinformation after January 13 and was fired from her job because of it. But they always seemed uncertain somehow, as if they didn’t believe themselves they would become a majority and the norm, just wanting, using the opportunity to say everything they had on their minds, everything, and afterwards, according to God’s will.

Two decades have passed since then8, but has anything much changed? Hardly. And the Pribaltikai are still around: they always appear on the scene whenever the great “phantom pains” of contemporary Russia take a turn for the worse—pains from the loss of the soyuz nerushimyy—the unbreakable union—at times as those who not only destroyed it back then but who still today impair all attempts to recreate it, at times as those who, in twenty worthless years of independence, understood their mistake and will be the first to join the revived empire as happily as they did in 1940.

When the Russian war with Georgia began, I decided to read what the Russian news media had to say about it—and was shocked by the miraculous multiplication of falsehoods. It didn’t matter which internet site, newspaper, or television program—they all explained things more or less the same way: Fascist Ukrainians and Pribaltika volunteers, who would later organize pogroms for Russians in their own countries, were fighting on the Georgian side, while an assassination attempt had been prepared for Medvedev and who was leading all of this? The CIA, of course. The evidence was as clean as that in the short Soviet film from back in the day about the trial of the Lackeys of Reaction, the Baptists—here, look, wherrre their book’s printed?—New York!

I know that axiom of political science: first, that the constant noise of propaganda is an essential activity of an autocratic government’s survival; second, when the news media outlets serving the government do not have public checks and balances, they start believing what they say and, encouraging and goading themselves, start manufacturing rubbish of ever more grotesqueness.9 And third, this mean, lying discourse is a product of the government, which cannot on any account be identified with an ordinary Russian.

I know why this is repeated so often in the Western space. After all, no one wants to believe that this nation is doomed to a hideous system; we want to hold on to the hope—for ourselves and for the Russians themselves—that a democratic change is still possible. This is, of course, naive. It cannot be doubted that the Russians are not imperialists or propagandists by nature. However, homo democraticus naturalis doesn’t exist in Russia, either. Life there was always permeated with official propaganda that affected all of its citizens, be it via differing means and dimensions.

For example, let us take Venedikt Erofeev’s book Moscow-Petushki or Yuz Aleshkovsky’s Kangaroo—their marvelous comedy and mad flights of parody comes from entirely unfunny things: a thinking person’s efforts to show the emptiness of the official discourse and to free themselves of it, if only briefly. You can’t help admiring the protagonists’ determination to avoid compromises with the government, even if the result is an existence completely beyond the boundaries of society. In any event, more often one becomes so accustomed to the polluted atmosphere that it starts to be considered the norm. Even knowing he’s deceived in the public sphere, the Russian begins to believe it can’t be different anywhere else (knowing: when you can’t check for yourself or learn of other opinions, when you are not just directly, but also via hints, fed a synchronized “truth,” knowing shortly becomes something between feeling and suspicion). And he transfers this disbelief to other countries, to the entire world. Even my friend M., a writer from one of Russia’s largest cities, a sharp-minded intellectual who’s seen the world, liked to repeat the proposition (is it Foucault’s?) that the differences in opinion between East and West is programmed, and therefore illusory.

Of course, a naive belief in everything said in public isn’t a particularly good characteristic (although to me, for some reason, more sympathetic than a suspicious attitude); however, the Russians’ problem is that as many times as they’ve been deceived and made fools of, they can’t bring themselves to believe in absolutely anything. It seems to me that this is the source of the conspiracy theories that have thrived in Russia’s post-Soviet consciousness. It cannot be that significant events occur of themselves, that the reasons are those they appear to be at the first glance, while the results affect only the immediate surroundings; it cannot be that this news means only what it means; no, in reality (and how satisfying and grand to declare “in reality”) all of it profits someone else, who will make nice money out of it, increase their honor and power; all of it was created and planned by some influential secret group of people, possibly some other country’s government or their authorized organization (the CIA!). One way or another, a powerful and malicious intelligence is hiding behind every world trend.

Of course, this mindset was formed by longstanding factors—the insularity characteristic of the country, the unprecedented strengthening of the foreign secret service during Stalin’s rule and the general paranoia about foreigners (The Master and Margarita’s Berlioz and Homeless simultaneously think inostranets—foreigner—when they spot Woland on the park boulevard; there’s fascination in that word, and envy too, but most of all—suspicion and fear). But the laughter dies in my throat when I read an article in a regional Russian newspaper, nearly the lead story, proving that bird flu, at that time spreading through the world, was created by Chinese geneticists to destroy the Slavic race. The explanation of how they select victims was no less convincing: apparently, Slavic genes differ from other nations’ in that it’s the most resistant to alcohol—in other words, the Russians can drink more vodka. So there you have it: that hideous virus was designed to work only on those possessing this genetic structure.

[space]

Probably the most enigmatic saying in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment (a novel full of enigmatic sayings and thoughts) is spoken by that embodiment of the Russian folk character’s openness and kind-heartedness, Razumikhin: “we shall lie our way to the truth at last.” So maybe everything’s more complex, maybe it’s a specific program or philosophy? The belief that day won’t break without the blackest gloom? An Adamite’s plan of action: reach truth and purity through the darkest entry: nonsense, deception, lies?

III

Here I must say: on the other hand. On the other hand: what truth is it, hiding behind the other side’s Soviet propaganda and silly inventions? That Russia is an unlawful, violent, backwards country? Yesss… But what can you do with a truth like that? How do you live with it? Make fun of it, mock it all? Several excellent novels and several thousand jokes could come of this, but you can’t live your life only laughing; cheerfulness quickly gets bitter and turns into something even worse. Emigrate? Many do it, but not everyone will. (And when you emigrate, how will you deal with the fact that you’re that nation’s representative?) Try to change something? That’s no bed of roses, and in the contemporary system it leads straight to a great deal of trouble and government institutions.

Naturally, the reaction of a certain class is shame—shame of Russian history and customs, Russian barbarity and its abuse of other nations, Russianness itself. Probably all of its neighbors know this type: a mild and diffident Russian tormented by the conscience of a hangover, who attempts to reduce his countrymen’s guilt by friendly behavior and attention. At one multiethnic party I met an appealing young Russian woman who had recently visited Lithuania. She shortly announced her regret over the Lithuanian churches closed and demolished by the Russians in the nineteenth century (I replied that perhaps it wasn’t worth feeling sorry over this). Shame has become one of their most important and ruling emotions.

A more colorful variant of this type is the man who attempts to pretend he’s the representative of another nationality. I remember a friend of my father’s from Moscow, A., with a low level job in the foreign affairs ministry, who visited us just before Lithuania declared independence. It turned out that he, as befits a diplomat, was a huge fan of tennis, and we agreed to play a set at the Vingis Park tennis courts. Early Saturday morning they were closed, and we, without giving it much thought, climbed over the fence. “Let’s speak in English,” said A., “if someone comes and starts yelling at us, tell them I’m from England and have to play tennis every morning,” and went off to the baseline with an energetic step. At that moment he very much resembled a Russian actor playing a Westerner in one of the of classic detective thrillers or innumerable screen adaptions revealing the evils of capitalism.

Others don’t stop there; they seek an absolute transformation, change their language, name, and try to complete blend into their chosen nationality, usually one of the Western ones. The Lithuanian (and probably all Eastern Europeans) look at this life choice like they’re looking into a mirror, since their nationality doesn’t lack for cases of this sort, admitting the Russian’s great talent at reinvention and considering whether it isn’t another side of that same reticence and fear of foreigners. Actually, in A.’s case it was merely a moment’s fancy, as he really didn’t intend to turn into an Englishman. When the Soviet Union fell, he, a liberal and a Yeltsin supporter, was delegated to the Russian ambassador to an African country. However, in the early nineties, when Yeltsin ordered the army to attack the rebellious parliament, A., overcome with despair over this turn of events, killed himself. I cannot say that at the time, with everything turning upside down, I would have thought about A.’s behavior long. The sad news was, you could say, an epilogue to the prolonged cohabitation with this nation. But now, when I think of it, I am horrified—is it worth killing yourself over political ideals, however beautiful and important? And especially for someone like Boris Armenjevic, a calm, elegant Moscow bon vivant, a diplomat who wasn’t directly responsible for all of it? Who, in Soviet times, had to keep silent and justify much worse things? Whom the new era promised an excellent career perspective?

I assume that the particularly passionate Russian sense of justice was at work. It’s possible to patiently bear the greatest oppression and injustice for a long time, but if the talk progresses to the principle of justice, the system, and the like, then it must be spotless. It seems that this need for absolute purity affected the Russian attitude towards the history of the twentieth century as well. Yes, perhaps in the Soviet Union we were unjust, thinks the Russian: the killings, the Gulag, the KGB and the rest of it: but have our enemies, the West and America, always been completely just? Of course not, and it’s not difficult to find examples. You see, he says, and to this day the objections to the Soviet (or the contemporary) system’s faults are backed up by a crushing counterargument: you look at yourselves. And no one pays any further attention to the impropriety of comparing details rather than the whole, which, however you look at it, differs greatly. The black work of that same CIA or the fact of social inequality becomes an amulet to the Russian, offering at least a modicum of justice, at least somewhat justifying his existence, and he does not let go of it.

During the twenty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, in various locations, most often in Western Europe, meeting mostly with young Russians, I have had a number of opportunities to observe how this work of justifying his country occurs. At first an inverted pride dominated. When the “easterners” began talking about their country, to gab about post-communist absurdities, the Russians in the company hurriedly swallowed their mouthful and silenced the others: Come on now, there’s more anarchy on our roads than on yours! Our mafia is much worse! The prices are even higher! And behind this hovered the conclusion: Here, look at me; I live in this environment, and everything’s all right, I handle all of it and my knees aren’t knocking. And I don’t just live—I manage to be happy, to socialize and amuse myself in a way you’ll never manage to. Well, if you respect me, I could show you how. The proof of your respect—a toast to my health. Well, is it better? You’re one of us now? A friend? Then let’s get a move on! Nu, davaj, come on, let’s go, let’s move!

This argument of the feast at the time of the plague faded quickly, at least among intellectuals. It was too obvious a glorification of one’s infirmity; besides, even the sturdiest genes can only hold out so long against this style of amusement, after which the fairytale ends and an endless hangover sets in.

This is why the projection of Russia’s political role has returned in the last decades. Nothing very new has been discovered—this is either a nationalistic or a left-leaning perspective (obviously, the return of these old ideologies after the 1989 revolution, after the worldwide triumph of postmodernism, when it appears that the past has been disassembled and reconsidered down to the bone, strikes one in a peculiar way). A great deal has already been written about the ideologeme of “Holy Russia,” which experienced great sufferings while safeguarding some kind of grand truth for the world, but was not understood or appreciated by it; I recently had the opportunity to meet up with a left perspective in person, when breakfast with my friend M. in a Charlottenburg kitchen would carry on until midday and sometimes later.

On one thing we entirely agreed: the dominance of the idolatry of wealth, predatory ethics, the concentration of government in the hands of a few oligarchs, the falsehoods and corruption drove us crazy. However, when M. began to declare that capitalism, and capitalism alone, was to blame for all of this, I kept quiet. According to M., capitalism is indeed a demonic phenomenon, responsible for everything—corruption and social isolation, police brutality and poor service in government offices. However, the worst thing was is that it’s impossible to get your hands on this insidious capitalism. It’s a government structure? Yes, but not only that. An economic system? Yes, but not only. A social theory? Yes, but not only. The power of corporations and their propaganda? Yes, but not only. You could bring about a revolution, plant the government leaders and the oligarchs in prison, institute a regime of communal business, silence the neoliberal theorists and make the correct social teaching compulsory—and it wouldn’t be enough to finish off capitalism. It would go underground, masquerade as “a welfare state,” retreat to other countries and continents, and finally, into people’s unconscious, where, when opportunity presents, it would proliferate again. M. believes that the culture of resistance, of whom he considers himself a part, isn’t entirely pure either, as there are faulty offshoots within it as well, and cited one of the new Left authors.

In any event, M. had a concrete enemy. This confrontation offered him, an otherwise phlegmatic person, unbelievable energy, which he used for interpreting even everyday affairs—for example, the plodding speed of transferring money through a German bank—as an aspect of capitalism’s inhumanity (M.’s passionate arguments sometimes began to resemble Hugo Chávez’s proclamation that there would be life on Mars, but capitalism destroyed it). Undoubtedly, that this enemy is the same all over the world encouraged this bitterness, and M. was obviously pleased that he had a bond connecting him to other nationalities and with the West. In addition, he—and in his mind, I as well—were more fortunate than our colleagues from other countries, as we had had the opportunity to experience a true alternative to capitalism, the Soviet Union of the late twentieth century. M. considered his time period, distinguished from the Stalinist system by a complex cordon of arguments, as the most substantial realization of a socialist system.

The progress of science and industry that sent man into space, universal employment, free health care, a police force that, in contrast to today’s, did not terrorize the ordinary citizen but kept order, the intellectuals’ connection with the people—these were the arguments M. repeated, and at that point I could no longer restrain myself. My counterargument, that this was attained at the cost of a lack of freedom, would merely raise an ironic smile; to him, the word “freedom” was associated with the chaos of the Yeltsin period and neoliberal ideology. (“That Nemtsov,10 tell me, what does he want?” S., a fellow Russian asked M. “I don’t know,” M. answered, “freedom, apparently.”) According to him, the system was convenient for dissidents, too; after all, opposition sooner or later affected fame and a career in the West. Amazed that it was necessary to discuss things it seemed had long since been laid to rest, I would try to argue that universal employment was another name for mismanagement and laziness, and industrial progress went on only in the military sphere and produced nothing for ordinary citizens. That the contemporary materialism and corruption came from the Brezhnev period, when there was no less of it, just that it was hidden. That it was strange to speak of solidarity in a society where one half the population constantly spied on and reported on the other. That Putin—whom M. considered the embodiment of neoliberalism—by profession and in his thought is a typical product of the late Soviet era, and so forth. However, he would let these arguments pass by, and then I got tired of arguing…

The October revolution was defeated, M. spoke in a mild manner while sipping beer, it swallowed its children, but it remains a historical avant-garde reference point, humanity will continue to align themselves with it and sooner or later will achieve its aims (after all, the bourgeois system didn’t come into its own all at once, it needed more than one revolution). I looked at his brown eyes and thought of what place M., who I would wager is neither an imperialist nor a chauvinist and feels a sincere sympathy for the Baltic states, would assign to the Lithuanians? Will the Balts survive in his scheme of world progress or, if they resist, be destroyed, or, neither plentiful nor distinct, simply disappear in the great historical battle of change?

IV

Ty znal li dikiy kray, pod znoynymi luchami,

Gde roshchi i luga poblekshiye tsvetut?

Gde khitrost’ i bespechnost’ zlobe dan’ nesut?

Gde serdtse zhiteley volnuyemo strastyami? –

I gde yavlyayutsya poroy

Umy i khladnyye i tverdyye kak kamen’?

Have you known a wild land under a withering sun,

Where the bloom of the groves and meadows are faded?

Where cunning and carelessness pay tribute to malice?

Where the hearts of the inhabitants are driven by passion?

And where from time to time

Their minds are as cold and hard as stone?

Mikhail Lermontov, „Zhaloby turka“ “The Lament of the Turk”

Those Lithuanians born in the seventh and eighth decades are the closest to the Russians. We encountered their language and customs, arts and history from childhood onwards. We very well knew the places where valuable resources had been found in Siberia, Peter the Great’s reforms, and the turning points in A Hero of Our Time (not to mention the Soviet hagiography). At that point, other cultures, including that of interwar Lithuania, were much too distant and no more realistic than a fairytale. Since we had never laid eyes on an Englishman or a German, the English and German we learned in school were as abstract as mathematical formulas.

Although the world we grew up in was called the Soviet Union, it spoke Russian, and primarily Russians created and organized it. It was not a matter to rejoice over—it was full of military drills and hypocrisy, horribly monotonous, forcing a longing for something different. On the other hand, this has existed from time immemorial, from the mythical beginnings of civilization, something like the pyramid of Cheops, and it looks like it will exist for many millenniums to come.

Fortunately, it was just at that time that it became clear the builders of the pyramid had stolen the cement, and the Soviet Union began disintegrating so quickly no one could believe it. The whoosh! of its fall echoing throughout Eurasia left a schizophrenic mechanism in our souls worthy of a sequel to The Night Porter—a close and thorough knowledge of Russia, and at the same time, an understanding of the brutality, injustice, and broken lives its government had brought to Lithuania.

Regardless, it was easy to dislike that country. Not just because of the camps and prisons where our grandfathers and uncles sat (earlier many kept quiet about them, but now they spoke openly). After all, essentially everything Russian was associated with the Empire—if not the Soviet one, then that of the czars. The empire was the first debit against the account; even those in Russia who disagreed with it were a response to it, in other words, dependent on it. Even the literature that was so vibrant and memorable—wasn’t it the fruit of a certain mentality that was, in the public sphere, accompanied by a terrible negligence, if not violence? And—it’s distressing to even ask—didn’t those masterful word forms feed the same source as the lying fairytales of propaganda?

Unlike others, Germany specifically, who have worn their power in our latitudes, Russia has never sincerely renounced its imperial attitudes. Even today, driven by that same purpose, it muddies the political and economic waters of Lithuania. Ultimately, for the antipathy to remain alive, all that’s needed is contemporary Russian pop, that musical-television derivative, offering a daily sacrifice to money, sex, and pother. A monster with truly imperial intentions savoring its cynicism—actually, even more cynical than its American counterpart (which it copies in absolutely the majority of genres, styles, and reception) because it so badly wants to overtake and outpace it. Pop music pouring from Russian money’s media that our government does not control, justifying its lack of action with freedom of speech and choice; it’s what people are interested in. Pop, whose heroes are a stocky man with a bull’s neck and super-sexual dolls. You’ll run into them in the streets of our cities, too, next to an expensive restaurant, climbing out of the newest model Mercedes.

However, as often happens, from truthful premises we have drawn mistaken conclusions. The rejection of the Soviet heritage and Russia occurred via a mechanical transfer of accents. Giant names, signs, uniforms, etc., were blown away by the winds of change, which were undoubtedly necessary, but often limited, in the naive belief that a “Lithuanian” name would magically changes people’s habits and institutional traditions. All the more so since the mysticism of names and national slogans was actively fostered by the “silent resistance,” those who had all their lives been zealous props of the system (like, for example, our former school director, who, in 1987, wanting to prove to his students that the true celebration of the Lithuanian government was, if I remember, November 15, the day the Lithuanian-Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic was declared in 1918, invited none other than the historian Mykolas Burokevičius11 to help out, and a few years later was a leading participant in the anniversary celebrations of independence on February 16).12 However, what is most depressing is that the new social or political organizations’ modes of action are rather often reminiscent of something: the tendency to see things in black or white, the intolerance of criticism, the explaining of every failure as a plot (Russian, of course), the pyramidal style of rule… It was particularly disheartening to observe displays of this thinking among the most ardent enemies of the regime, in gatherings of dissidents or political prisoners.

Among intellectuals, the corresponding tendency could be called reverse communism. Its principle is quite simple: if the Russian communists assert one thing, then, without exception, the assertion’s opposite is correct. If Soviet ideology believed in, or even paid lip service to, social equality, then the truth is a market “as free as underwear elastic.” If Soviet culture was progressive, or at least paid lip service to it, then we’ll be so conservative that even ultra-monarchism with the Fraternity of Saint Pius won’t seem sufficient. If a Lithuanian grammatical construction corresponds to a Russian one, then it follows it’s a grammatical error—and so forth, and so on.

Perhaps falling ill with these post-colonial poxes was inevitable. Today, however, those who have never healed are down with a particularly serious cases. Snobbishness and counterfeit Westernism, expressed in American buzzwords, British suits, and “forgetting” the Russian language when running into Russians or other former citizens of the Soviet Union. Self-censorship of their own and others’ lives, eliminating the first twenty (thirty, forty) years, up until the point of studying at the Sorbonne, becoming a Euro-politician or an ace businessman. Under all of this lies an ancient means of making life easier without thinking—all of the blame for the evils of the past and today’s problems are piled on the neighbor. Roughly like this: if it weren’t for those Russkies, Lithuania would now be a hybrid between Canada and Finland; if not for those Russians, there wouldn’t be collaborators settled in the highest posts, corrupt clans, the news media’s insanity, and xenophobia—there wouldn’t be any evils at all. It’s particularly vile that politicians and officials of “the Komsomol generation” have taken up anti-Russian rhetoric, thereby assuring their place in government, but doing absolutely nothing to make the country the slightest bit less dependent on Russia in two essential spheres: material and spiritual energy. Even historical figures suffer from this kind of attitude: one radical acquaintance once declared he couldn’t forgive the Lithuania’s medieval rulers for failing to conquer the Grand Duchy of Moscow when they had a chance, and more than one! “Hold on,” my girlfriend retorted, “you mean you think it’d be better if the trigger to the nuclear arsenal would be in Vilnius now instead of Moscow, and the entire post-communist space would be listening to Radio Litovskoje instead of Russkoje?”13

[space]

However, the night follows every day. And when Lithuanians tire of accumulating wealth, of democratic procedures, of practicing self-control, they can’t find a better refreshment than their Eastern neighbor. Especially since it’s a return to the past, when we were all at least twenty years younger, remembering old times whose horrors time has covered with the patina of nostalgia, remembering adventures and intense experiences we can brag about to the young—and that’s why ordinary people pound in that same pop music, which is understood so much better than the Anglo-Saxon (in terms of language, and realia) and is so colorful, temperamental, and excessive. And the cynicism—it doesn’t vex at all, since the audience is on a similar, or in any event comparable level. Intellectuals longingly gaze at the misty expanses where bearded Orthodox saints and literary heroes shine with infinite love, pain, and forgiveness. There, neither a calculating mind nor philistine bourgeois boredom dominate; instead, it’s broad gestures and spontaneous action. Unequivocal toil for the noblest aims is suddenly replaced by a bender bad enough to lead to wrist-slicing; generosity and philanthropy by crime. And then a powerful desire arises to shake off all the tension and routine with a single gesture, and vanish in those expanses… The intellectual knows he’s playing with fire, but—from a fairly safe distance, which gives this game even more of the pleasure of transgression.

And the Lithuanian, sitting in the kitchen of an apartment in the capital of a European Union and NATO country, purchased with a mortgage in euros, just now returned from a vacation in Turkey or hightailed home from the summer cottage in a new Peugeot, is flooded by a boundless kindness, and he says: Oh, so many bad things are constantly going on in the world, isn’t it all relative; after all, time goes by, and why hold on to the past, better to up and forget it, after all, those Russians are so sincere and witty, are they to blame for what happened before they’d even been born—and on the other hand, are we all spotless, do we always act justly, after all, how did that song from the time of Sąjūdis go: “We’re beggars ourselves, we’re hangmen ourselves”? And whatever it was that happened to my countrymen, my grandparents and uncles, I’ll up and forgive them. I’ll look so nice when I say, like the Russian cartoon character Leopoldas the cat, “You know what, let’s be friends.”

Let’s leave him sitting, swooning from his own magnanimity. You can forgive a hundred times, but if there’s no reaction from the other side, when there’s no regret, no determination to improve—and unfortunately, the fact is that contemporary Russia wants to “be friends” only on its own terms, without rejecting an iota of its historical mythology, traditions of collective behavior or psychological structures—then it’s obvious nothing will come of it.

[space]

This is why there probably is no alternative for a thinking person except to wait. To wait for Russian society, a change in the Russian consciousness, the third Russian republic, as one Russian writer called it. To wait doesn’t mean to turn away or ignore them, but rather to not let them out of sight, to take an interest in them, as well as talk to and interact with them. Not to be silent about one’s own outlook on Russia’s present, to talk about how difficult it is to free ourselves of the Soviet heritage—but we’re freeing ourselves anyway; reminding them of those parts of the past that were hidden from them, or those they don’t want to remember themselves. To not surrender to either the masochistic charm of “the good old days, when we were together,” nor the grim pride of “you’re barbarians, we’re the West.”

Despite all the balance sheets of the past, despite our differences, which grow more obvious with time, something remains. Not just admiration for works of literature, film, and music, but for the broad gesture, the deeper attitude and the humanity, more distinct than that of a Lithuanian who spends his life worrying only over the decoration of his garden fence in order to keep the evil forces from the wide world from getting in. An admiration of some Russians’ ability to ignore their circumstances, to stand up to their surroundings, to hold on to their beliefs (after all, not everyone has the fortune to be born in a democratic country), and to stubbornly strive for the top of their calling.

And I believe that one day—probably only when the Russian summer during which I appeared in this world is close to an end—I will once again be able to go to the window looking out on Dzerzhinsky’s yard, Moscow Street, or a cemetery in an African country and shout: “Hey, katsapy, do you hear? Pashka, Baryga, Mitia, Boris, I’m talking to you! Davay, let’s get together!” “Okay, davay,” they’ll shout back, “let’s meet!” “And wherrre?” “Behind the nine-story maybe, or at your place, in the kitchen! And not now, but sometime around nine! Or else, you know, in that in-between heaven of Bulgakov’s!” “And what will we do?” “Well, we could play football or ice hockey, we could be cops and robbers, or, you know, the battle of the knights—let there be battles of the knights, at least we’ll behave knightly for once—and then we can sit on the bench and rest, and later get something to eat—Kostromos cheese, you know, or Moscow dumplings, if they are any—and talk, and tell stories about the government and about what a hole this place is, and tell jokes, one after another, grains on a long chain of wit, and then tease one another, laugh at each other, let off steam, and then maybe sing a bit, too—something, not bumčikas,14 but some really old folk songs, like the ones A. sang in a rich bass when he was here visiting at Easter, and then—

space

“So, that’s it? Or maybe you wanna come at me, bro? Never mind, at seven then—you hear, katsap?

This essay was originally written in 2011. Translated by Elizabeth Novickas

1. An example of the Lithuanian Soviet-era slang used throughout this essay. Most are of Russian origin.

2. A military hat worn during the Russian Civil War.

3. A slang word for Russians from Ukrainian originally meaning “billy goat.”

4. National movement in Lithuania in the late 1980s, which led Lithuania to independence.

5. After “Montana” jeans, a West German brand of the era known in the East for its quality, and particularly fashionable among Russian youth, even after it had gone out of fashion among the Lithuanians.

6. A military force performing the function of civilian police in the USSR.

7. A documentary film about the events of January 11, 1991, when the Soviet military attempted to crush the declared independence of Lithuania. Nevzorov later founded a movement by the same name.

8. This essay was written in 2011

9. Author’s note: A rumor spread after the terrorist attack at the Beslan school in 2004—supposedly, hired Blacks took part in it. This is how the scene was set: a hung-over sergeant saw the faces of some dead assailants covered in soot, and suddenly put it all together: oh, it’s all clear, this is an international plot if they’ve even recruiting Blacks!

10. Boris Yefimovich Nemtsov, a politician opposed to Putin who was assassinated in February 2015 on a bridge near the Red Square.

11. The leader of the Moscow-backed communist party formed after the Communist Party of Lithuania voted to separate from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in December of 1989.

12. Incidentally, where are the literary works portraying these impressive about-turns? Only Ričardas Gavelis and Juozas Erlickas’s satires come to mind.

13. Radio Russkoje was a Russian pop station widely broadcast in Lithuania.

Laurynas Katkus (b.1972) is a Lithuanian writer, essayist and translator. He studied Lithuanian philology and comparative literature in Vilnius, Norwich and Leipzig. He was awarded various grants and fellowships, among others, of the Iowa University International Writing Program and Stockton College. He has five translated books in English and German, most recently a novel, Schwankende Schatten, (Klak Verlag, Berlin, 2022). For more, see www.laurynaskatkus.lt

© Deep Baltic 2022. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.