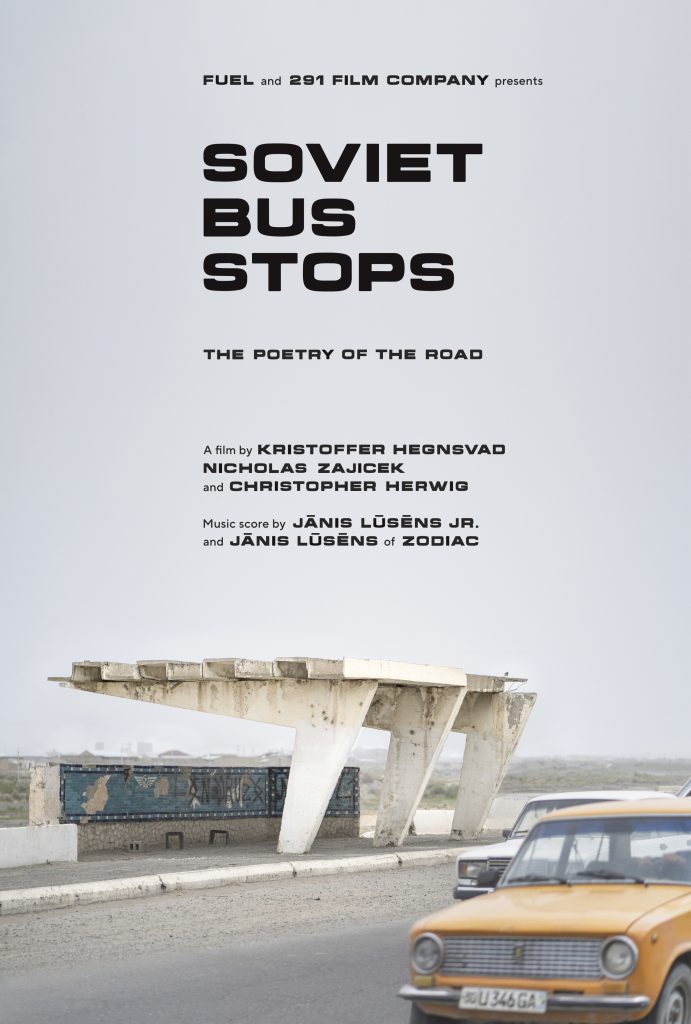

A new documentary, Soviet Bus Stops, reveals the story of the unexpectedly artistic or elaborate transport stations found across the former USSR, an outlet for creativity in a closely controlled system. The film is the brainchild of Canadian photographer Christopher Herwig, who has spent more than a decade fascinated by the phenomenon, criss-crossing the 15 former Soviet republics in search of weird and wonderful bus stops. The soundtrack of the film has a Baltic flavour: the Latvian group Zodiac (known as Zodiaks in Latvia), formed in 1980, who created futuristic sounds reminiscent at points of Kraftwerk and, while being little-known in the West, achieved wide popularity across the Soviet Union, selling 20 million copies of their first album. In this article, Herwig tells us a little about the project, and we include an interview with the driving force behind Zodiac, the well-known Latvian composer Jānis Lūsēns.

Architecture, like anything else during the Soviet period, was under strict centralised supervision. While art and grand monuments were expected to advance the state narrative of communism as paradise on earth, sometimes the benign bus stops were overlooked. As a result, hundreds of architecturally distinctive bus stops are now scattered across the former Soviet republics. Built by individuals who decided to follow their own artistic urges, they found a way of expressing local and artistic ideas, in this small form. Their bus stops were built as quiet acts of creativity against overwhelming state control.

In 2002, Canadian photographer Christopher Herwig came across his first of these distinctive pieces of architecture, and has since pioneered a bus-stop-hunting trend from Kiev to Vladivostok. The bus stops he has chronicled represent an astonishing variety of original styles and types, from the strictest Brutalism to exuberant whimsy. Herwig’s resulting photography books have become international bestsellers and are critically praised as gems on architecture and Cold War history.

Shot over a period of seven years, the documentary Soviet Bus Stops follows Herwig on several bus stop hunts, listening in as he seeks answers as to how these unique creations came to exist. Puzzled by their origins, and without historical records, Herwig tracks down several of the creators and finds inspiration and a strengthened belief that the special bus stops need to be remembered.

Today, tainted by the memory of the era in which they were created, many bus stops have been torn down or are disregarded as strange and embarrassing. Few people see them as the phenomenon Herwig does. He considers them to be one of the largest and most diverse architectural collections in existence. Their rejection of established forms is key to this appreciation. Herwig’s twenty-year-long efforts in photographing hundreds of bus stops is an attempt to memorialise them before they are all demolished.

Soviet Bus Stops accompanies Herwig on his unforgettable road trip, as he meets some humble and charming bus stop creators from Ukraine, Estonia, Georgia, Belarus and Lithuania. The remaining bus stops represent the stories of people who created small acts of poetry against all odds.

About the soundtrack to the film, by Latvian band Zodiac, Herwig says: “Five years ago I came across Zodiac’s first album in a record store in Moscow and was blown away by it. It was reminiscent of the ’80s and yet like something I’d never heard before. I was never sure if and how we would be able to get the music for the film but from the moment I heard it I wanted to make it happen. Eventually I managed to track down Jānis Lūsēns and, through his son Jānis Lūsēns Jr. and music agents at www.micrec.lv, I was able to start a conversation about getting them involved in the project. For me, the music was so important for a number of reasons that related also to the bus stops. The bus stops are fun, creative and whimsical and I wanted music that would reflect this mood and carefree attitude. Although the bus stops were made during the Soviet era, many reflect individual creativity more than a state standardised design or political agenda and I wanted that spirit to come through. Finally, people too often lump the whole period and region together as being Russian and forget that nearly half of the people living in the Soviet Union were not Russian. The bus stops often celebrate local traditions and cultures and I wanted to bring attention to this amazing Latvian band I came across.”

How did the band come together, and is it true you all were studying music together?

It happened in 1979, all the band members were students at the Latvian State Music Conservatory, each in their own departments – trumpet, contrabass, trombone; however, these specialisms were not used in the band’s work. The band was basically formed by two people: myself as the composer and arranger, searching for new sounds, and the other person was drummer Andris Reinis. In the studio we recorded all the basis and the other band members joined only for specific songs. I have to add that Zodiac was never a touring band.

What were the biggest challenges when recording the first albums?

The biggest challenge for us as students was working in a professional recording studio, which was back then one of the best recording studios in the Soviet Union. It was in Riga, a branch of Studio Melodiya. Its manager Aleksandrs Grīva was in fact the producer of Zodiac in the contemporary understanding of the word. He was also the sound director, determining what sounds to use, how to create the form, and how the drummer should play. So part of the band’s success is also his work as a producer, additionally guiding the visual design and art for both albums.

Can you tell us more about the synthesiser Felix, which year was this?

As we were living in a closed-off country, the former Soviet Union, no foreign consumer electronics were available legally to us. Foreign synthesisers were imported here by Soviet diplomats who sold them here for extremely high prices, which of course for us was not an option. However here in Latvia we had two guys who were fond of everything electronics and who wanted to create something beautiful from available electronics parts from the Soviet army. One of these people was Feliks Staņevičs, who currently works in music electronics, microphones etc., and he created the first MUG prototype in really unimaginable circumstances. If in the United States this was done by numerous researchers and scientists with a lot of resources available, then here it was done by one person with a relatively good outcome. We got from Feliks one such synthesiser and tried to use it in the movie as the score base, and my son Jānis – when turning it on – said that “yes, every sound fits”. That is the peculiarity here, yes – basically these sounds cannot be repeated. This instrument is unique.

What exactly did you want to achieve with the music you were composing at that time?

We were not thinking about achievements back then. Of course it was our affection for disco music, electronic music, space, Kraftwerk, Jean-Michel Jarre which for me was very close to my heart and we – to the best of our abilities – tried to realize something like this here in Latvia. We were not thinking about any kind of fantastic success. Of course, thanks to the very Western album artwork and the producer work of Aleksandrs Grīva more than 20 million copies of the first album were sold.

Do you know how popular the first albums were among the people? Do you know any direct feedback from the listeners at that time?

The phenomenon of this was the fact that the people were tired of the content of the Soviet popular music, from the likes of Kobzon and Magamajev on state television. Ours was a very Western approach and I think that the fact that the music was instrumental, spacious, we had no limits or censorship when it comes to text, in addition to the really high quality artwork of the album – all of this gave the feeling that finally in the Soviet music shops there was a Western album available. And basically with the first album we broke the old Soviet music traditions and after that a lot of bands sprung up, looking for their musical style.

Do you remember your first TV appearance – on Mysterious Galaxy – which can still be seen on YouTube? When was this and what were your feelings back then?

That appearance was something resembling a disco, there were filming crews there for some Latvian television show, I think Rainbow (“Varavīksne”)… or maybe even for Soviet state television. We didn’t have any kind of feelings, as we just had to stand there and repeat a pre-recorded song a few dozen times. As we were also more of a recording studio band, I cannot really call this experience a public appearance. It was more a filming process.

For today’s youth who do not know what the life in the Soviet Union was like – how was it to create art back then? Did you have to consider consequences often?

Yes, we need to understand that the Soviet Union was a closed-off territory with KGB agents and people who could snitch you out from every gathering. However, I must say that those who did not openly express any anti-Soviet slogans or did not openly go against the regime – they were relatively left alone and just observed. Technical capabilities were limited and of course lyrics were subject to censorship. As we had no lyrics, this really did not affect us. However, as I said, Aleksandrs Grīva could arrange it for us on a very high level that our work was not subject to censorship at all.

The sound of your band back then was extremely specific. Where did this sound come from?

The sound came from my friend, composer Mārtiņš Brauns, who unfortunately passed away, and his dream about an Arp Omni synthesiser that he kindly lent me for the recording of the album. We also used the synthesiser Arp Odyssey, as well as the synthesisers of Feliks Staņevičs and Vilnis Kazaks. The capabilities were limited and the recording itself also happened on an eight-track band where we mixed two tracks together to get the next six free. It was chemistry work, cutting the bands and gluing them back together. From today’s standpoint the process was really very amusing.

When did you understand that you have fans and followers and that you have made it as a musician?

Yes, very interesting. I knew back then that the album was very popular but I really did not meet crowds of fans as we were not touring, we played no shows. We were a recording project. However, a few years ago, after requests from a producer group in Moscow to relaunch the band in a way that it could play on the stage, then of course after the concerts there were meetings with a lot of fans who still possessed the first album and wanted to have the album signed even 40 years after its release.

What did you as a band do after the fall of the Soviet Union?

The fall of the Soviet Union was really very longed for and awaited and this came to pass. As I am an academic musician, a composer, a lot of opportunities opened up for me in the genre of theatre music, rock operas, academic operas – I have composed two very successful kids’ operas that have been played numerous times – and also now I am continuing to work with meditative and improvisational music at my music house Ozolu School.

All images credit: Christopher Herwig/Soviet Bus Stops

You can pre-order the soundtrack album for Soviet Bus Stops from fuel@fuel-design.com

© Deep Baltic 2022. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.