by Steve R Dunn

The thriving modern republics of Estonia and Latvia emerged from the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and are still threatened by the revanchist policies of the USSR’s successor state. But the fact that they exist at all is in large part due to the [British] Royal Navy and particularly the role it played immediately after the First World War in helping fight off the expansionist ambitions of a post-Armistice Germany and the greed and aggression of the nascent Russian Bolshevik Empire.

In 1918, the Baltic was ablaze with a range of conflicting polities. All along the littoral, a plethora of factions staged a bloody and vicious conflict for control of the region. The Bolshevik Red Army and Navy fought to bring the region under Communist rule; German-Baltic Landwehr were intent on making a new German client state; White Russians were bent on reinstalling a tsarist monarchy (and taking back the Baltic states for their old rulers, the tsars). Then there were local freedom fighters, at war with all and often with each other; and even the regular German army, forced by the Allies under Article XII of the Armistice to remain in place as a reluctant barrier to Communist expansion.

Much against the wishes of the Admiralty, the Royal Navy was thrown into this maelstrom. Only small ships were deployed: light cruisers, destroyers, minesweepers, submarines, motor launches, eventually even an aircraft carrier. They were tasked with containing the Red Baltic Fleet battleships and cruisers based at Kronstadt, near St. Petersburg.

The navy had been given this difficult task because neither Britain nor France wished to commit troops to a new conflict. It was a cheaper and lower-political-risk decision to use ships, a plan supported to the hilt only by Secretary of War Winston Churchill. However, through the navy, Britain could provide sea-based artillery support, prevent a breakout or raids by the Bolshevik fleet and supply arms and ammunition to the armies of the Baltic states.

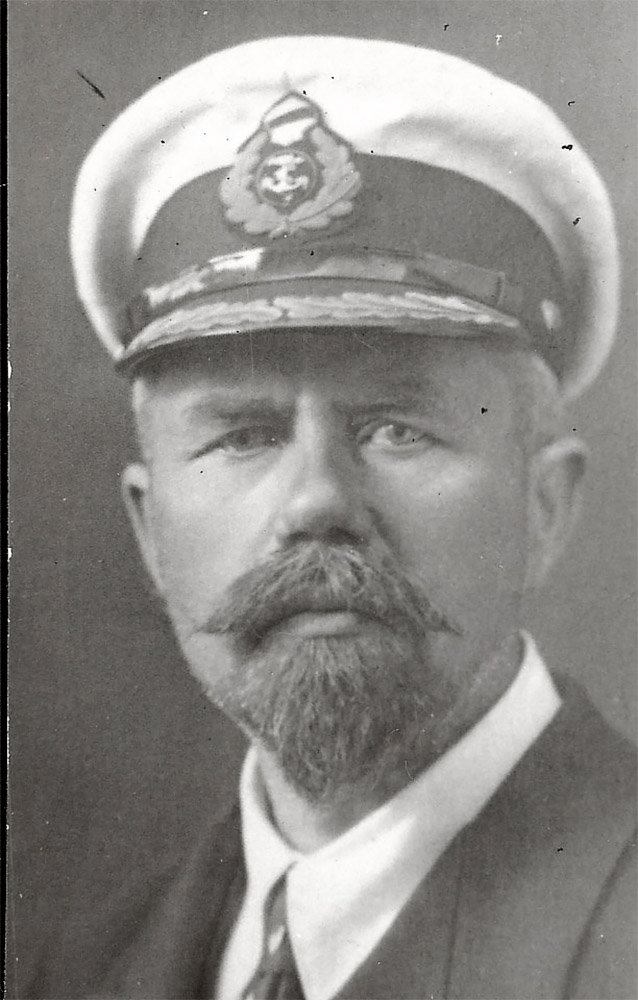

And so, on 26 November 1918, Rear Admiral Edwyn Sinclair Alexander-Sinclair CB, MVO, Twelfth Laird of Freswick and Dunbeath, and his second-in-command Captain Bertram Sackville Thesiger, set sail with a flotilla of light cruisers and destroyers for the Baltic Sea.

Thirty-five-year-old Johan Laidoner had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Estonian Armed Forces on 23 December. That was also the day Laidoner began the fightback. Escorted by HMS Calypso and the destroyer Wakeful, he landed 200 men at Kunda, in the Bolshevik rear area; they caused panic, destroyed supplies and severed communications before retreating, all the time covered by gunfire from the Royal Navy. By 1900, the ships were safely back in Reval (Tallinn) harbour, without any interference from the Red Navy.

This assault, and the previous destruction of a railway and bridge by light cruisers Cardiff and Caradoc, occurring as they did close to the Baltic Fleet’s base at Kronstadt, infuriated War Minister Trotsky. He ordered the immediate annihilation of the vessels at Reval, stating “they must be destroyed at all costs”.

The task of fulfilling Trotsky’s wish for the destruction of the British forces was allotted to Member of the Revolutionary War Soviet (the Revvoeyensovet) of the Red Navy at Kronstadt, Deputy Commander of the 7th Army and Commissar of the Baltic Fleet, twenty-six-year-old Fyodor Fyodorovich Raskolnikov, previously a midshipman (michman) in the Tsar’s navy.

His plan was for a task force comprising the battleship Andrei Pervozvanni, cruiser Oleg and destroyers Spartak, Avtroil and Azard to undertake the operation. The destroyers, under Raskolnikov’s direct control, would enter the Reval roads and bombard the port, bringing to action any ships therein. If superior forces were encountered, they were to retire on Oleg, with the battleship further back as heavy support. The action was slated for Christmas Day.

At the appointed hour, only Spartak and Andrei Pervozvanni left port, the others being either away or out on patrol. When they all finally rendezvoused, Azard was found to be out of fuel and Avtroil delayed by an engine breakdown. The operation was put back until the 26th.

Accordingly, at 0700 on St. Stephen’s Day, Raskolnikov, aboard Spartak, declared his intention to start the attack. But first he stopped to fire on Wulf (Aegna) and Nargen (Naissaar) Islands (both of which lie across the entrance to Reval harbour), ostensibly to see if they were occupied and armed. He then captured a small Finnish steamer which was sent to Kronstadt under a prize crew. These delays were to prove his undoing.

For at Reval, the local authorities had decided to hold a noontime banquet for the Royal Navy officers and crews to thank them for their support. Ladies were to be provided “for hire” as dancing partners. But the preparations for the festivities were interrupted by the sound of gunfire – the attack on the defensive islands – and then by the unpleasant noise of shells dropping in the harbour. Urgently, the “recall” signal was given; sirens blared continuously, and British sailors ran for the quayside and their ships. Thesiger had held his command at two hours’ notice for sailing and soon the first vessel left the harbour. It was the destroyer HMS Vendetta. Shortly afterwards Vortigern followed her and then Wakeful, which had lived up to its name. Calypso and Thesiger were immediately behind, and Caradoc weighed and went to full speed at 1205, by which time Vendetta had already opened fire.

When Raskolnikov saw the smoke of the three destroyers leaving port, he immediately turned Spartak away, heading for Kronstadt, perhaps intending to hide in the Finnish skerries or find protection under the guns of the Oleg.

HMS Wakeful opened fire on Spartak at around 1220 and Wulf Island was passed fifteen minutes later. There was chaos on board the Russian ship. Shells were falling around them, a blast damaged the charthouse and bridge, charts were lost, and the engines proved unreliable. Then with a sudden bang she ran aground on the Divel shoal and stranded. Raskolnikov despatched a final signal to his base; “all is lost. I am chased by English”. At 1245, Spartak ran up the white flag.

Thesiger put a boarding party on board. She was leaking badly, with her propellers and rudder torn off. The ship was filthy and the crew generally happy to be prisoners. Vendetta towed Spartak back to port. Once anchored, the Bolshevik vessel was still filling with water so the crew were instructed to raise steam for the pumps; they decided to hold a ship’s Soviet meeting to decide if they should. Armed Royal Marines convinced them of the necessity. As for the Soviet Navy’s commissar and mission commander, Raskolnikov was discovered hiding under twelve sacks of potatoes and taken prisoner. It was rumoured that he had on his person photographs of himself “torturing and murdering the old aristocracy”.

Around 1700 the British ships landed their “entertainment parties” and the banquet, delayed but nonetheless mightily enjoyed, took place.

Papers captured with Spartak revealed that Oleg was at Hogland (an island in the Gulf of Finland about 112 miles west of Petrograd) with instructions to bombard Reval. Although he had orders not to attack Russian vessels, Thesiger also found in the documents a message from Trotsky saying the British ships should be sunk. This seemed to Thesiger to be a casus belli and he gave orders for an immediate departure.

At 0050 on the 27th, Calypso weighed anchor and, in company with Caradoc and Wakeful, set out to find the enemy. Around 0500, Thesiger observed a destroyer passing on the reverse course; it did not see the British ships and Thesiger resisted pleas to open fire. But he did order Vendetta and Vortigern to depart Reval and find her.

At Hogland, there was no sign of the Red cruiser. Thesiger set up a line of patrol, Caradoc to the north, Calypso south and Wakeful in the middle and in that formation began to cruise back to Reval; if the destroyer sighted earlier turned around it would run into his line of advance.

The Soviet destroyer, which was the Avtroil, seeking Spartak, ran into Vendetta instead, fled from her and came across Vortigern. She then turned east for Kronstadt and met Wakeful, went north and ran into Caradoc and finally south where she was intercepted by Calypso. Thesiger had previously ordered that he wanted to capture the Russian vessel. Caradoc had fired on her at 1135 and Calypso at 1150; ten minutes later, surrounded by five Royal Navy ships, Avtroil hoisted a white flag. A prize crew took her back to Reval.

The Estonian navy to that point had comprised one vessel, the ex-Russian gunboat Bobr, now the Estonian Lembit, capable of only 12 knots and armed with two 4.7-in guns and four 11pdrs. Johan Pitka, head of this proto-navy, had pleaded with Alexander-Sinclair for two Royal Navy destroyers, a request refused by the admiral. But Thesiger was now able to oblige. He presented him with the two captured Russian destroyers. At a stroke, Pitka gained two modern, fast ships and an actual navy to command. He named the new recruits Wambola (ex-Spartak) and Lennuk (ex-Avtroil). Estonia was a naval power in the Baltic.

(Place names have been given as they were known to the Royal Navy at the time).

Steve R Dunn is a naval historian and author. This article is based on his book Battle in the Baltic: The Royal Navy and the Fight to Save Estonia and Latvia, 1918-1920, Seaforth Publishing (Barnsley 2020, 2021)

© Steve R Dunn 2024

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.