by Damiano Cerrone – SPIN Unit

Asking the right question

What can Instagram say about culture? An even better question may be: can Instagram actually say anything at all about us? The answer is no, of course not. But this is not a nihilistic one, nor an elitist dismissal of social media: Instagram says nothing directly about culture and people because social media reveals less about society than it does about the way society makes use of social media. Instagram can tell us much about cultural practices and, in our specific area of interest and expertise, urban space. It is the way we interact with the medium—social media in this case—that makes studying Instagram pictures a big deal: if we know what we are looking for, of course. It is the way we use the medium to frame certain objects, spaces and ourself within the city that speaks out about the everyday and the occasional. Right, because if we just take images from our physical or digital albums, sort them all out in one single montage, all the several thousands photographs we now carry in our pocket, all that we see is the obvious. All that we see are the individual trees in a forest, the grains of sand on a beach, time on a timeline.

Our job as researchers is to ask questions. The beauty and joy of doing this in academic institutions is that we are relatively free to formulate these questions, although this depends on who is funding the research – or if anyone is funding it at all. So we decided to create a non-profit organisation called SPIN Unit, which soon morphed into a consulting firm, to gather a group of academics from different research fields and ask not the right questions but the questions that were relevant to us. One of these questions aims at understanding how our surroundings affect our self-perception. The nature of the urban architecture around us determines whether we will take a self-portrait — a selfie — and what will be included in it. It shapes how we see ourselves and how we want to be seen on social media. We study the urban meta-morphology, the intangible forms of the city.

But let us go back to the reason why we ended up studying social media data. As scholars and citizens of one city or another, we found high-end urban projects quite disappointing, unable to produce and foster interesting new experiences. At the same time, alternative groups, local initiatives, temporary uses and informal activities have had great success in this task of transforming the image of the city and creating contemporary icons of urban life. Benchmark cases such as Telliskivi in Tallinn, Löyly and Suvilahti Helsinki, Co-op Garage in St. Petersburg, Ex Mattatoio (Ex Slaughterhouse) in Rome and more that we haven’t studied yet, contribute to this effort. In other words, we are witnessing the broad and international success of informal processes that, in many cases, were actually hindered by local governments. At the same time, those projects that have recently been backed and promoted through formal planning have hardly ever become cultural icons of their respective cities, or entered the urban collective consciousness in a deep, meaningful and personal way.

Participatory planning it is as old as 1971, when the U.S. department of transportation held seminars to develop the inclusion of public citizens into the planning process. Local organisations, creative entrepreneurships and sometimes just individuals are already planning the city by themselves and they are capable of producing the most attractive and contemporary “monuments” of their cities. There are infinite reasons why this is happening, and apart from large-scale bribes and exchange of favours, one key factor is that society and cultural practices are changing far too quickly for the bureaucratic machinery of a masterplan. The information technology revolution is fundamentally rewriting our society, remodelling our activities and cultural practices; conversely, education in architecture and urban design has not changed accordingly, producing a new crisis in these fields. Somehow, our current practice of planning and building cities is out of sync with the preferences of the everyday users of those same spaces.

The current challenge in urban and transportation planning is to supply a new type of ever-changing supply of adaptable urban spaces to host activities which may not be satisfied through long-term planning but only through fast, informal, versatile speed-planning. In other words, while it is crucial to plan for long-term perspectives, it is now essential to have a form of “real-time” planning to satisfy contemporary needs.

Cultural analytics

We found comfort and satisfaction in the use of “cultural analytics” to understand more about the current anthropological landscape of the city. This approach, developed by Prof. Lev Manovich almost ten years ago, uses large image archives independently produced by people themselves (crowd-sourced) to learn more about cultural practices and the city. Because we ourselves constantly share images of our everyday life on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Flickr and so on, this is where social media data becomes useful. Of course, more private moments tend to be shared through instant messaging apps such as Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, Viber or Snapchat; which is why we choose to explore the public sphere of social media. We focused on Instagram because it allowed us to download and analyse all publicly shared images with exact geographic coordinates for each picture. This way, as researchers, we can relate a certain activity we read in the pictures with the place where is taken. For ethical reasons and because of potential sampling bias, we decided not to follow the timelines of single users, although it is completely possible to do so and does not require any complex algorithms. We looked instead at general behavioural patterns. We analysed a large number of pictures, usually in numbers proportional to the population of one city and its popularity among tourists, just by using the pictures themselves, their geographic coordinates and the date and time when they were shot, with no extra information that could easily disclose the identity of the users. We have used these methods to carry out academic research, like in the case of “A Sense of Place”, but we also use deploy these methods to analyse culture and politics.

All the blather

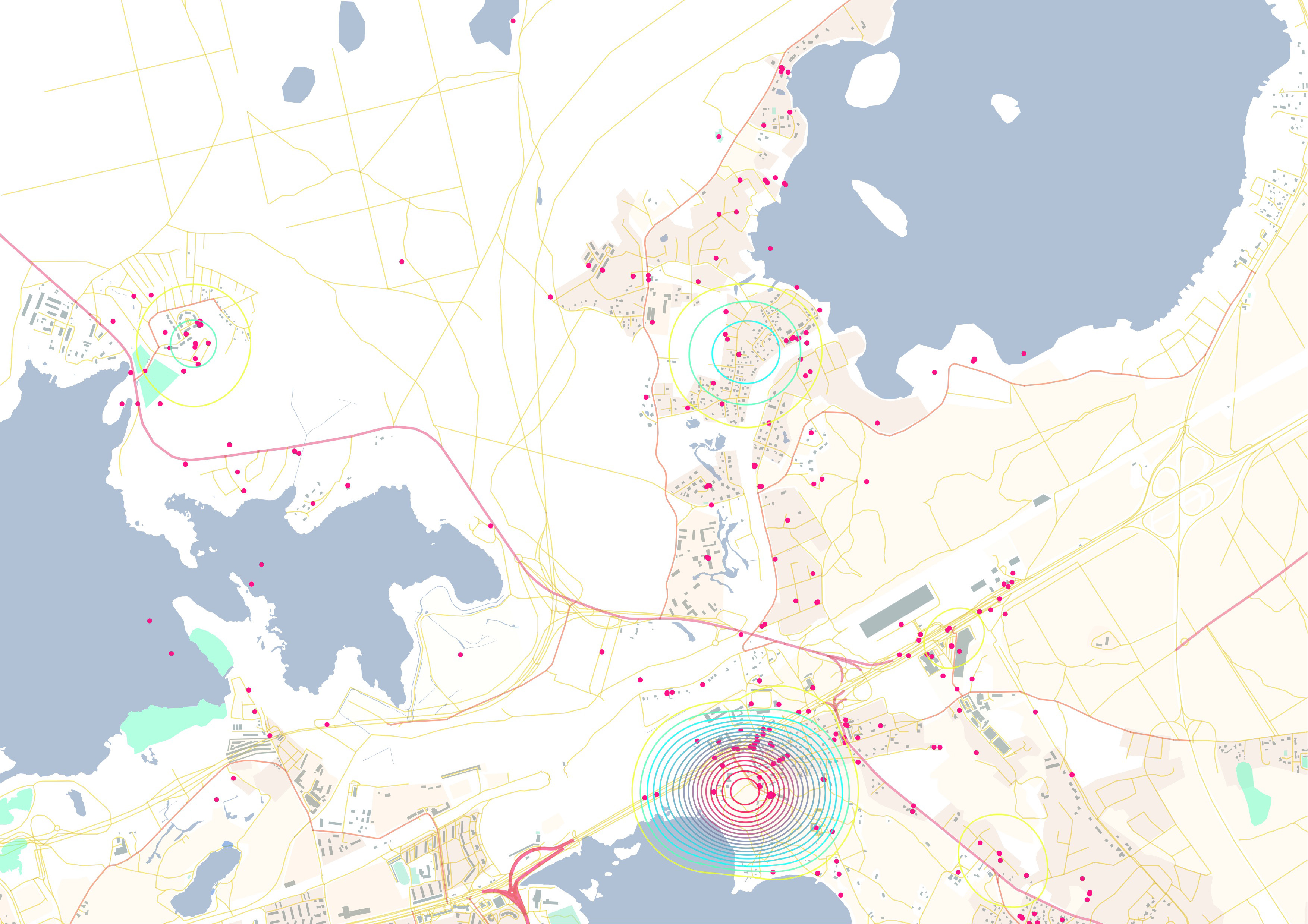

The city of Tallinn has recently begun the process of building a new urban highway running along the eastern shore of the city. This is an old plan – perhaps not aesthetically but at the very least conceptually. There are different reasons for building this new road: the main one being to relieve the city from the high volume of freight traffic to and from the harbour and the north-eastern suburbs, where residents rely heavily on cars.

Many European cities are not only discouraging the construction of urban highways, but they are also demolishing and repurposing those transport infrastructures that cut through the city or that are built through or along natural features. But our main interest was all the blather coming from political figures who in the past had already opposed the idea of evidence-based decision making. One of the main arguments circulating was that building the road is reasonable because the beach is not formally a recreational area, as the administration considered it as wasteland. Claims were also made that building the road would not harm the community, since the beach was mostly a place for anti-social behaviour and the local population felt no attachment to the place.

We met with Kristi Grišakov to discuss this issue. As citizens and researchers in Tallinn, we knew the area had some value for the local community and that it was not primarily a place for anti-social behaviour, but we needed something more to support this argument. So we tapped into a sample of Instagram pictures taken around the Russalka beach and studied what type of activities were taking place there and during which time of the year. What we learnt was quite clear: the Russalka beach was way more active than we expected, and we expected its social life would be displaced by the construction of the road. People use the beach for recreational, leisure and sport activities, and they do it actively throughout the year, regardless of the season. These results could be backed up by traditional surveys. However, it is hardly likely that the political party that pushed for the construction of the new road will embrace such conclusions, as they dismantle the politicians’ non-evidence-based decision making.

Find out more at: http://www.damianocerrone.com/portfolio/reidigram/

Baltigram

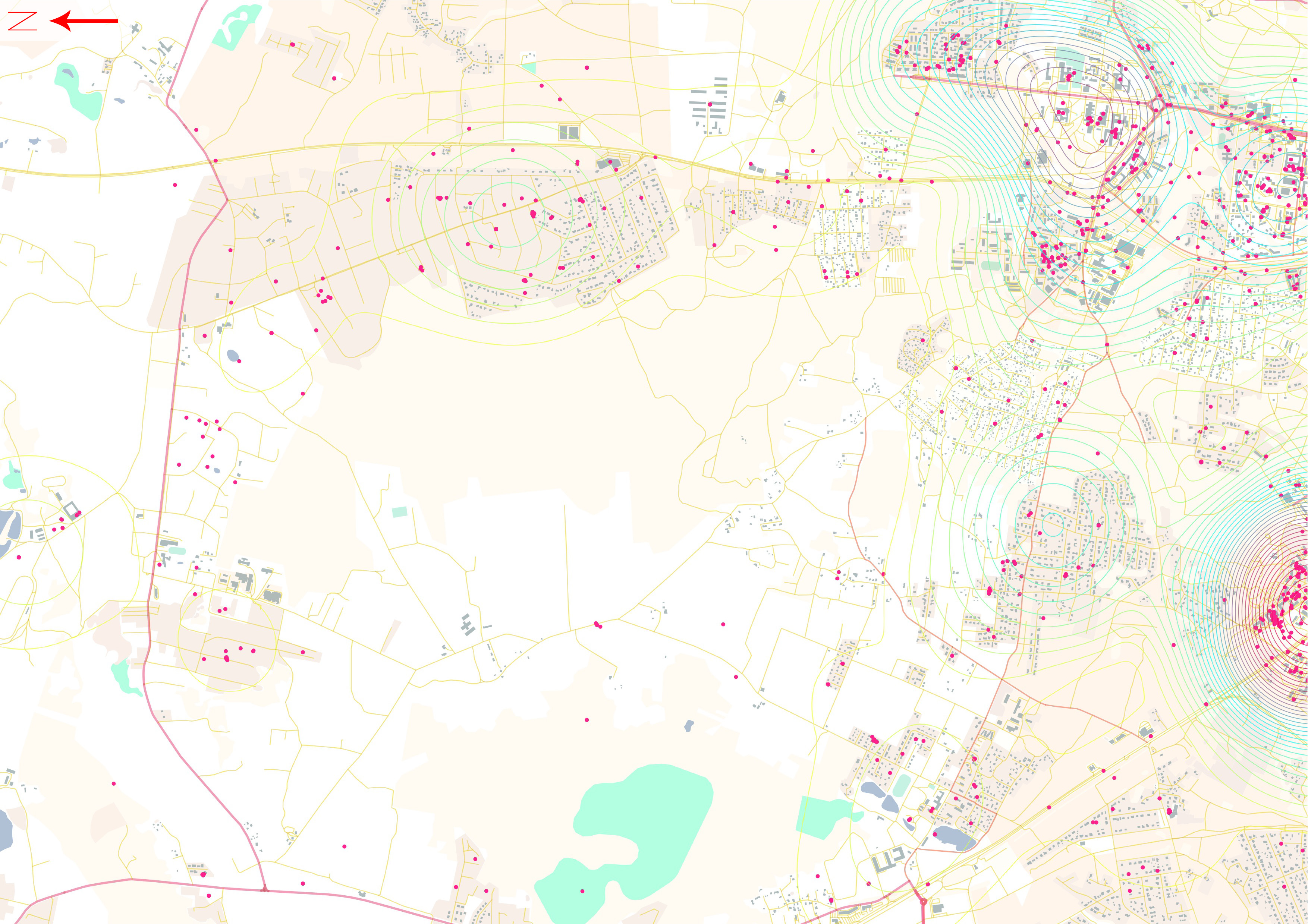

Something more, however, was needed to get to the core of the close ties between the Baltic cultures and the nature of their urban spaces. The Baltic countries are one and three. Three political states, different in their heritage, languages and customs. At the same time, a common history, Soviet occupation and post-socialist economic policies have produced a shared cultural landscape, which is truly visible in the architecture of their capital cities. In Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius we can find the medieval cores of the Hanseatic League (“old towns”), the mass housing of the Soviet time and single-family housing suburbs at the edge of the city. Our conjecture is that somewhere, hidden in the everyday urban life, there exist further elements of a cultural heritage shared between all three states. These are elements that we could extract and analyse to find a common, more united way to life in the anthropocene of the post-socialist era.

We needed to find an information layer that best represents people in the cities, a source of data revealing how people perceive and see themselves in different urban environments. We wanted to use real, crowd-sourced data to reveal the psychological environment of the Baltics through a readily accessible window into the self-perception — and the public projection of the self — of the Baltic peoples. For this purpose, we teamed up with media theorist Prof. Lev Manovich and data analyst Raul Kalvo to tackle this project. We came to the conclusion that we could indeed rely on selfies as our data source. By examining the pose and what elements are framed in the background of each picture, we can produce a clear and reasonably unbiased map of how we perceive ourselves in relation to each geographical location.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j1r8xtyeEbs&w=560&h=315]

A close-up selfie that leaves plenty of space to have an architectural landmark in the background remarks a strong sense of belonging, both as local or as tourist. In this type of picture, architecture becomes the centrepiece of the shot and it is meant to highlight to social media followers the location of the photo’s human subject or subjects. A selfie taken of a reflection in a mirror, to show the entire body of the selfie taker in a closed room, focuses on the individual rather than the architecture or the city. By collecting thousands of pictures, we are then able to break down the wealth of data at our disposal into those singular choices, and map behavioural patterns to understand what social media users are proud to share, what type of environment they prefer and how they like to represent themselves in those spaces. This is because the representation of oneself in space is a relevant cultural expression of one’s social group, sense of belonging, and the way the individual lives or acts in the city.

As we gathered a sample of publicly shared geolocated Instagram pictures, we started to notice some interesting patterns: we could not distinguish pictures taken in the Soviet housing districts of Riga from those taken in the same type of district in Tallinn. So we have further geographically filtered Instagram pictures based on the type of neighbourhood they were taken in. There are three kinds of neighbourhoods common to all the Baltic states: the “old town” area, the Soviet mass-housing blocks, and the suburbs. Our analysis revealed that each type of urban morphology produces its own type of single or group “selfie.”

In the old towns of the three capitals, Instagram users include architectural landmarks to clearly establish their presence in these iconic spaces.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZCRU8yh2EnM&w=560&h=315]

In the Soviet mass housing districts, the selfie is decontextualized. The subject’s image occupies most of the photo and the background is not shown.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8etke1Bh4Ik&w=560&h=315]

In contrast, the photos taken in suburbs and shared on social media portray families engaged in outdoor activities. These photos favour backyards of private houses and local natural areas, and often show children.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1dQ2E2HprA&w=560&h=315]

These examples reveal how our surroundings affect our self-perception and how having a common architectural history produces a common culture, as portrayed on social media. The nature of the urban architecture around us determines whether we will take a self-portrait and what will be included in it. It shapes how we see ourselves and how we want to be seen on social media.

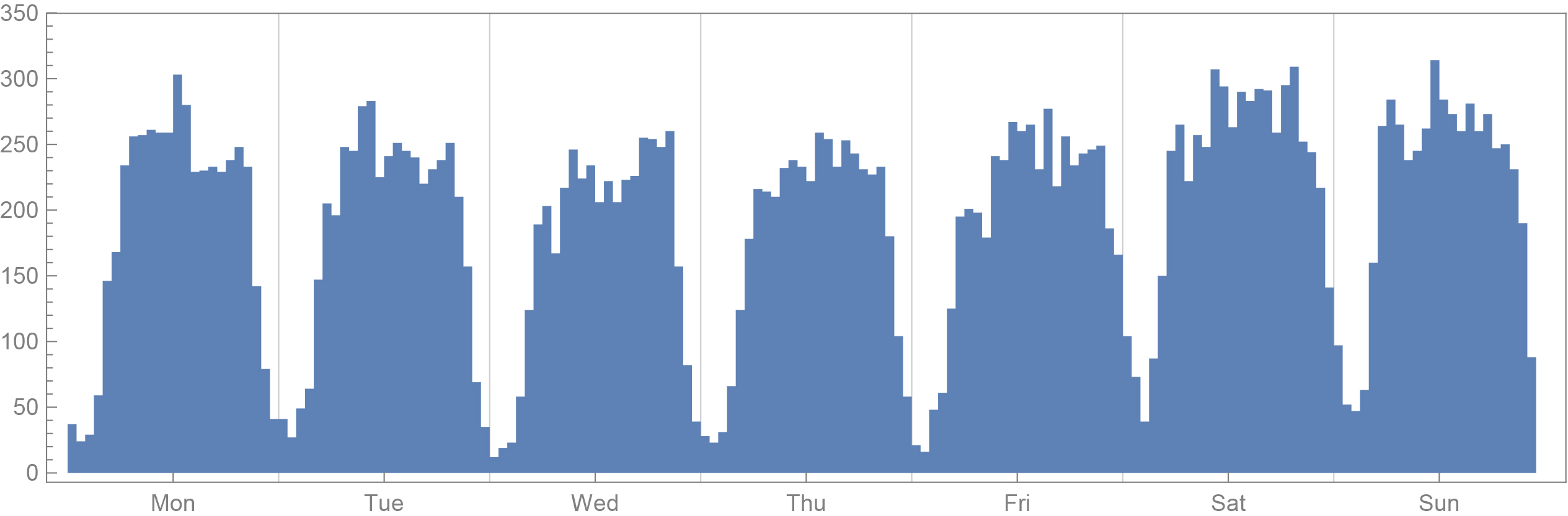

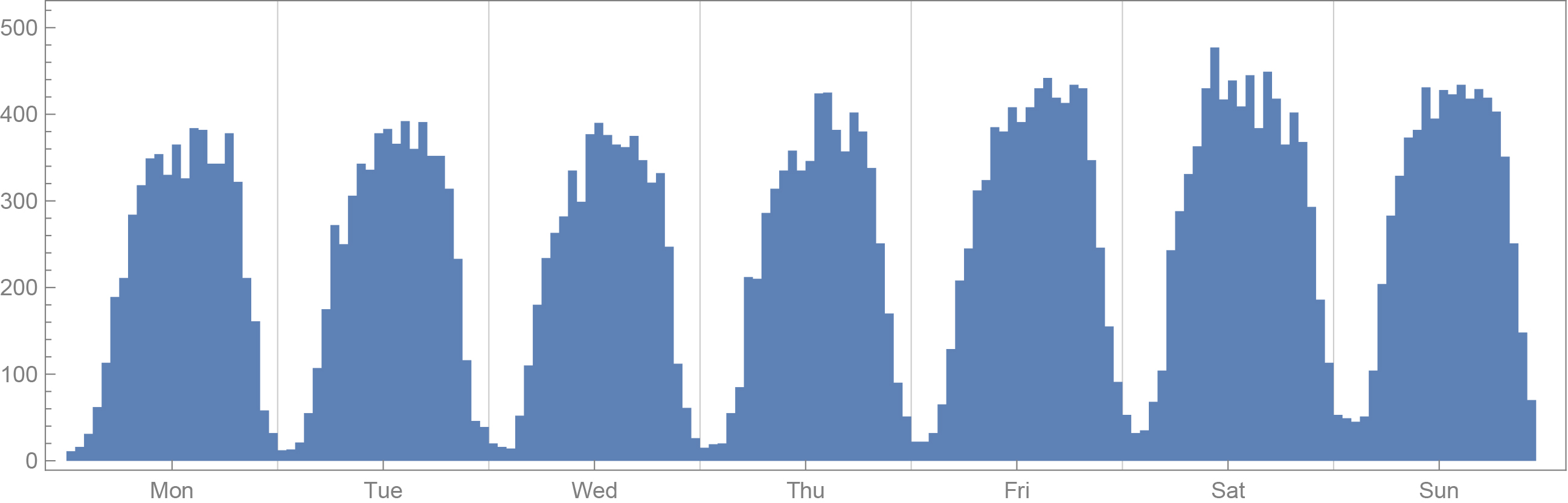

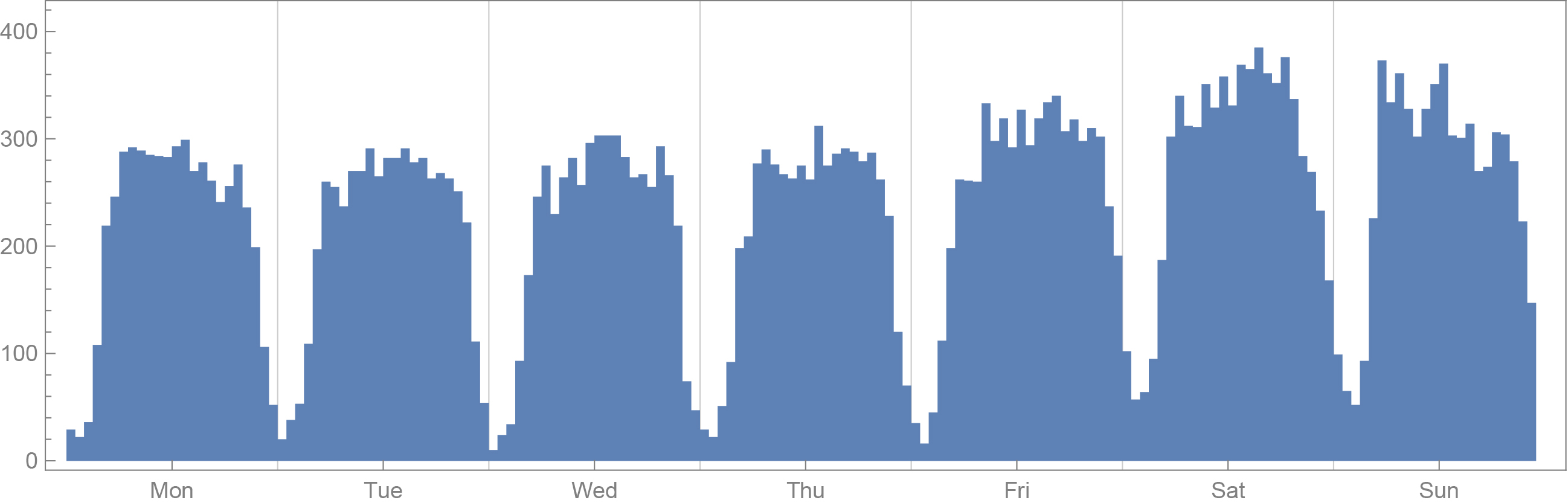

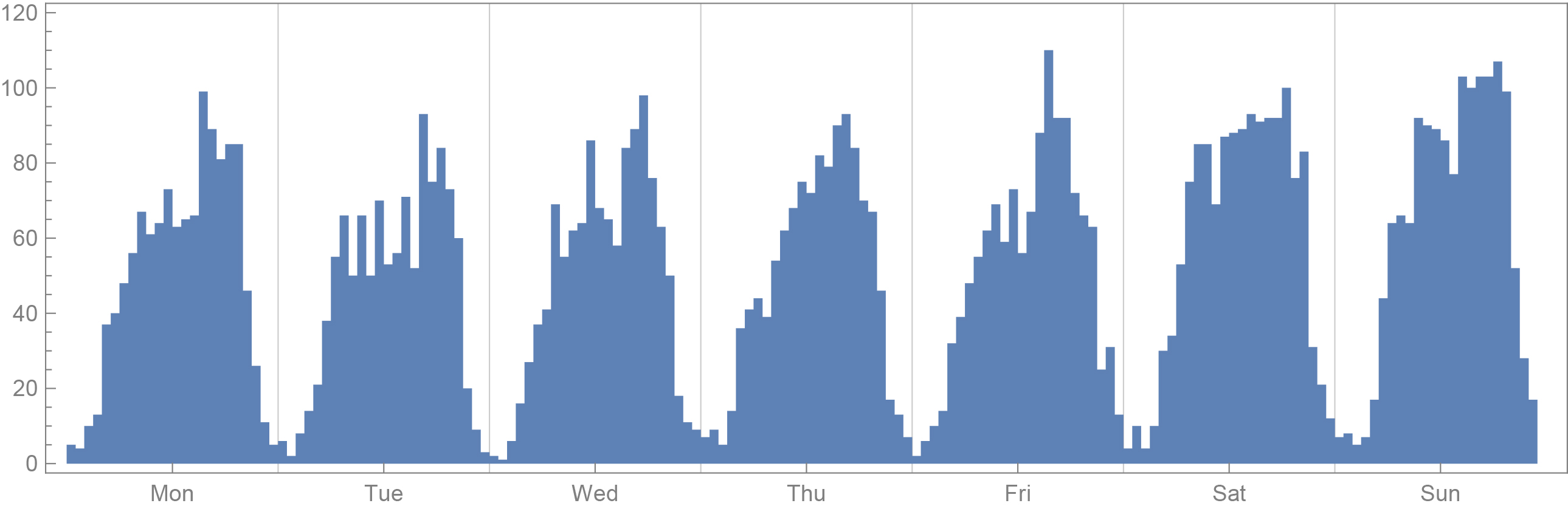

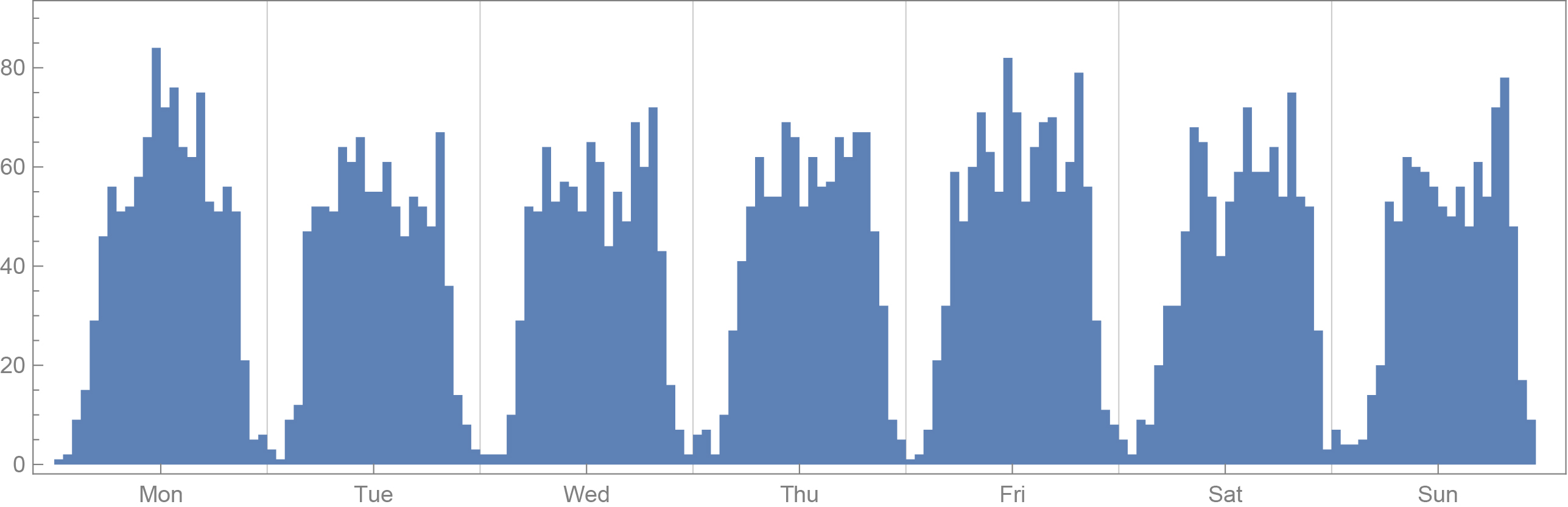

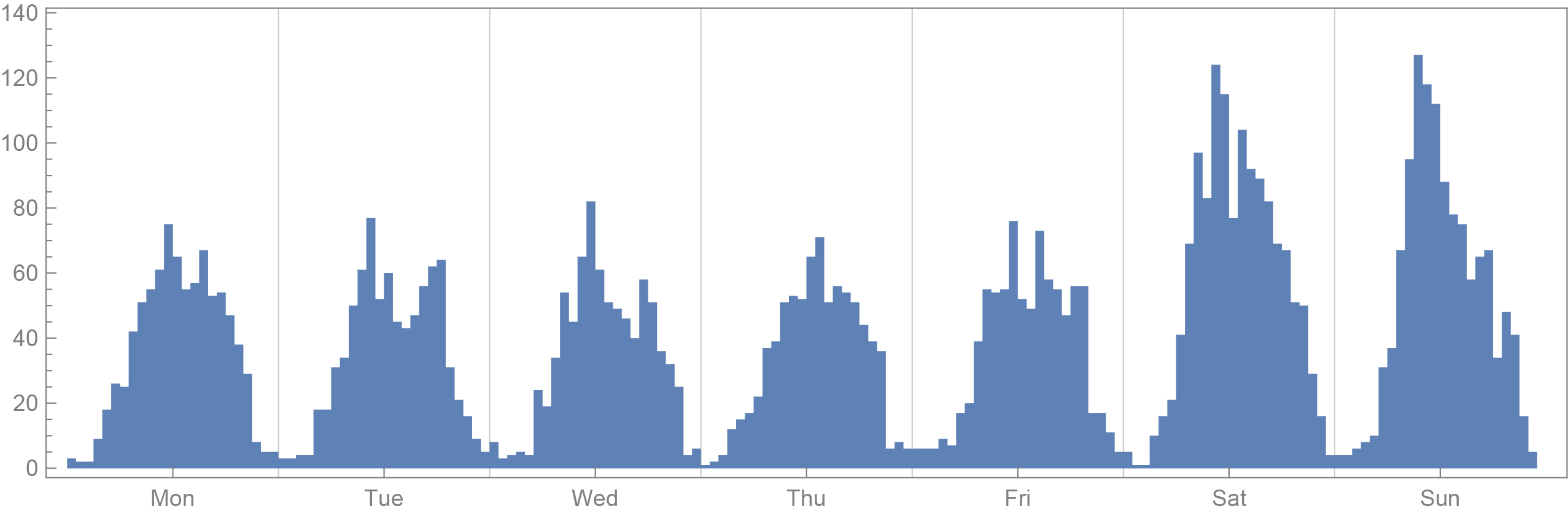

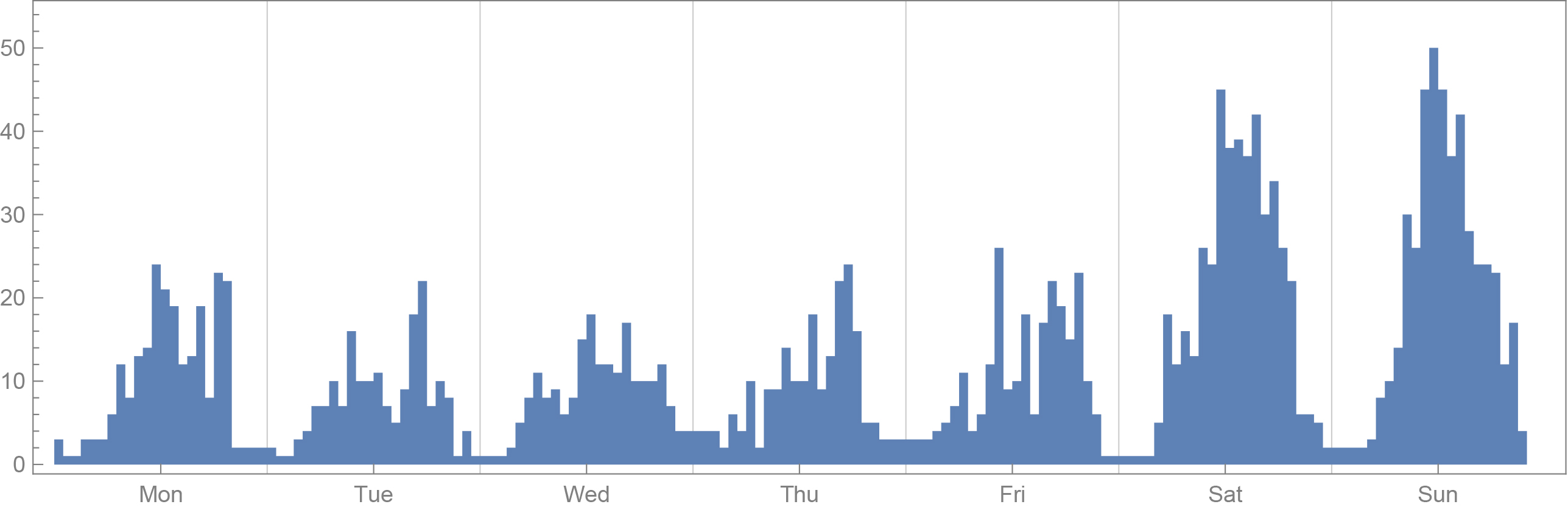

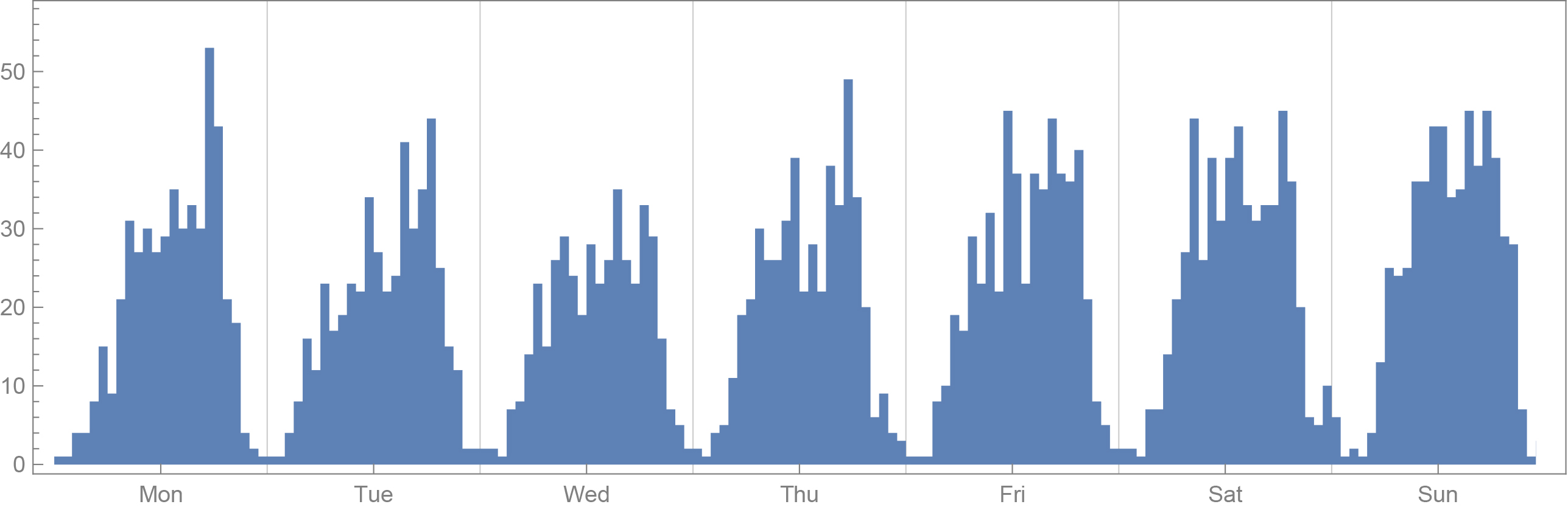

Temporal patterns

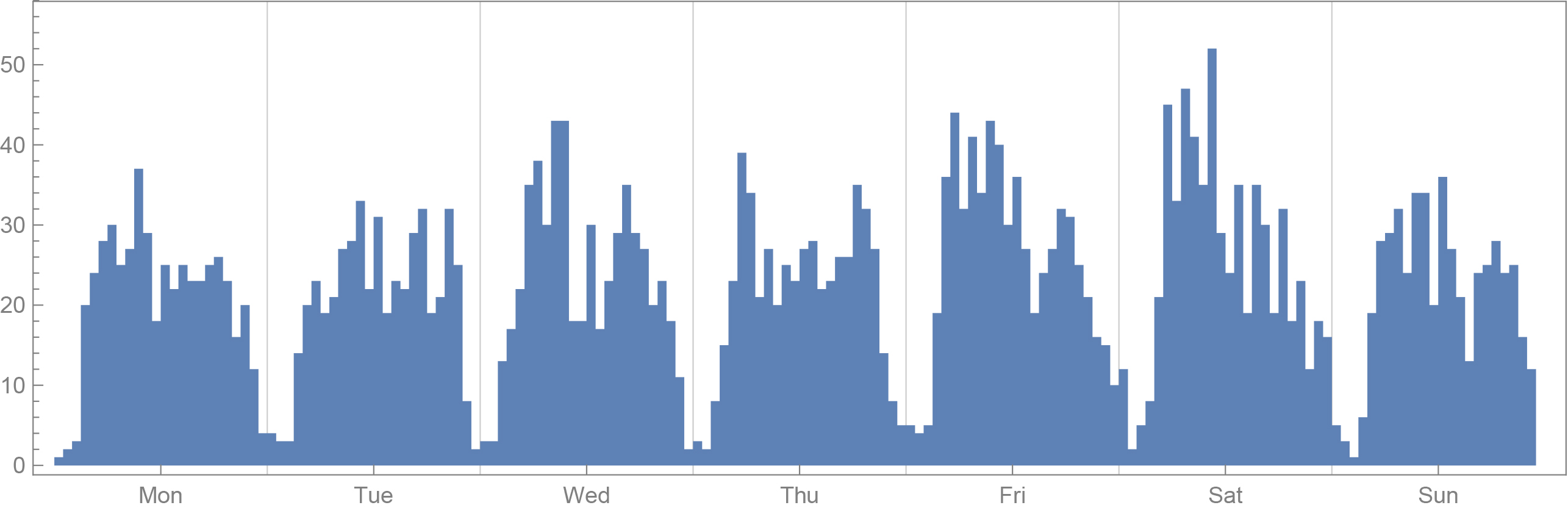

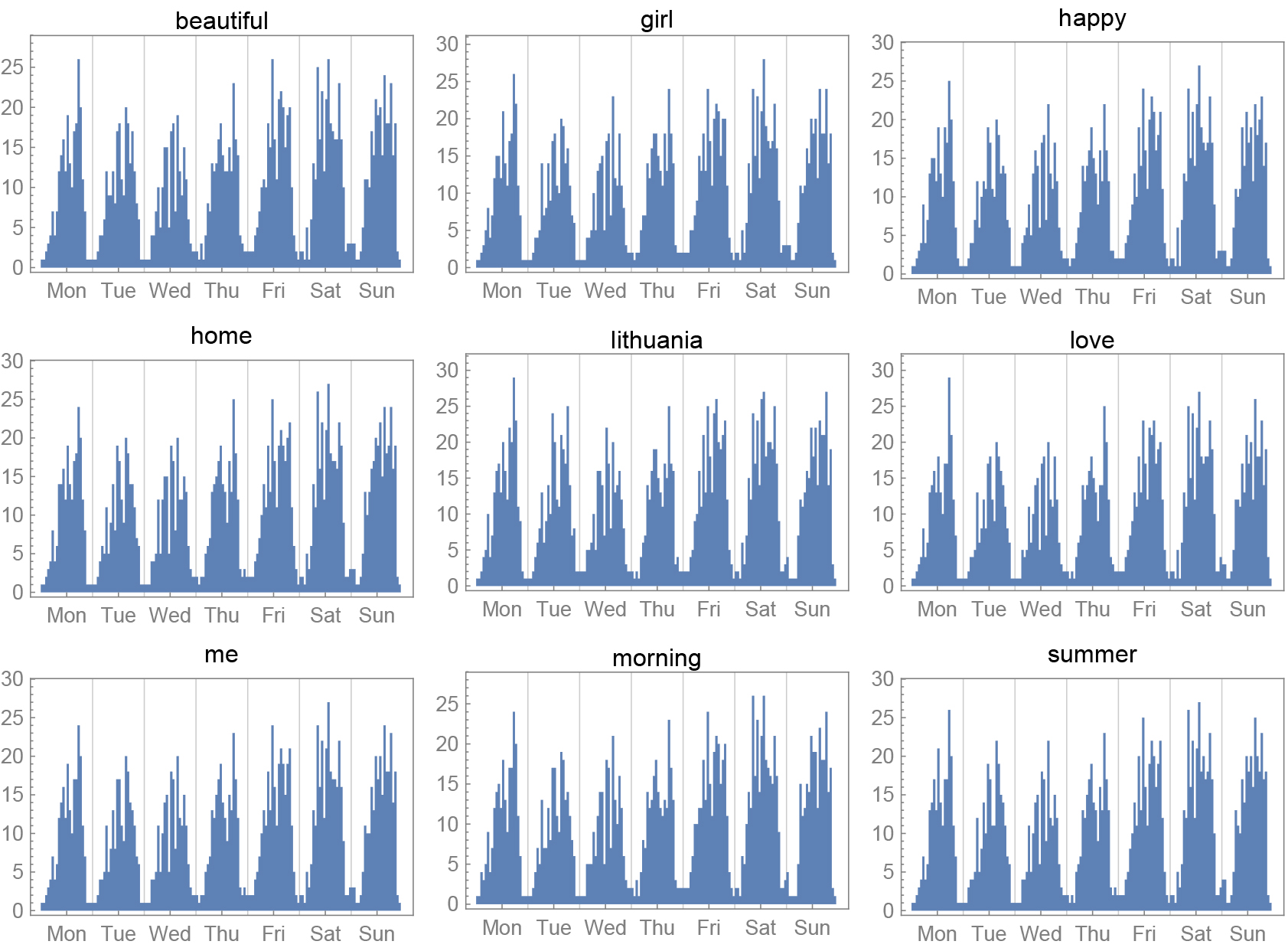

The following graphs show the number of pictures posted on Instagram every hour of the week, in each of the three cities. For each city, we show the different trends in each of the three areas of interest – the old towns, the Soviet districts, and the suburbs. The trends are consistent across analogous geographic areas in the three cities, but less so across different areas of the same city. That is to say, as far as Instagram trends go, Tallinn’s suburbs have more in common with the suburbs of Riga than with Tallinn’s own Old Town.

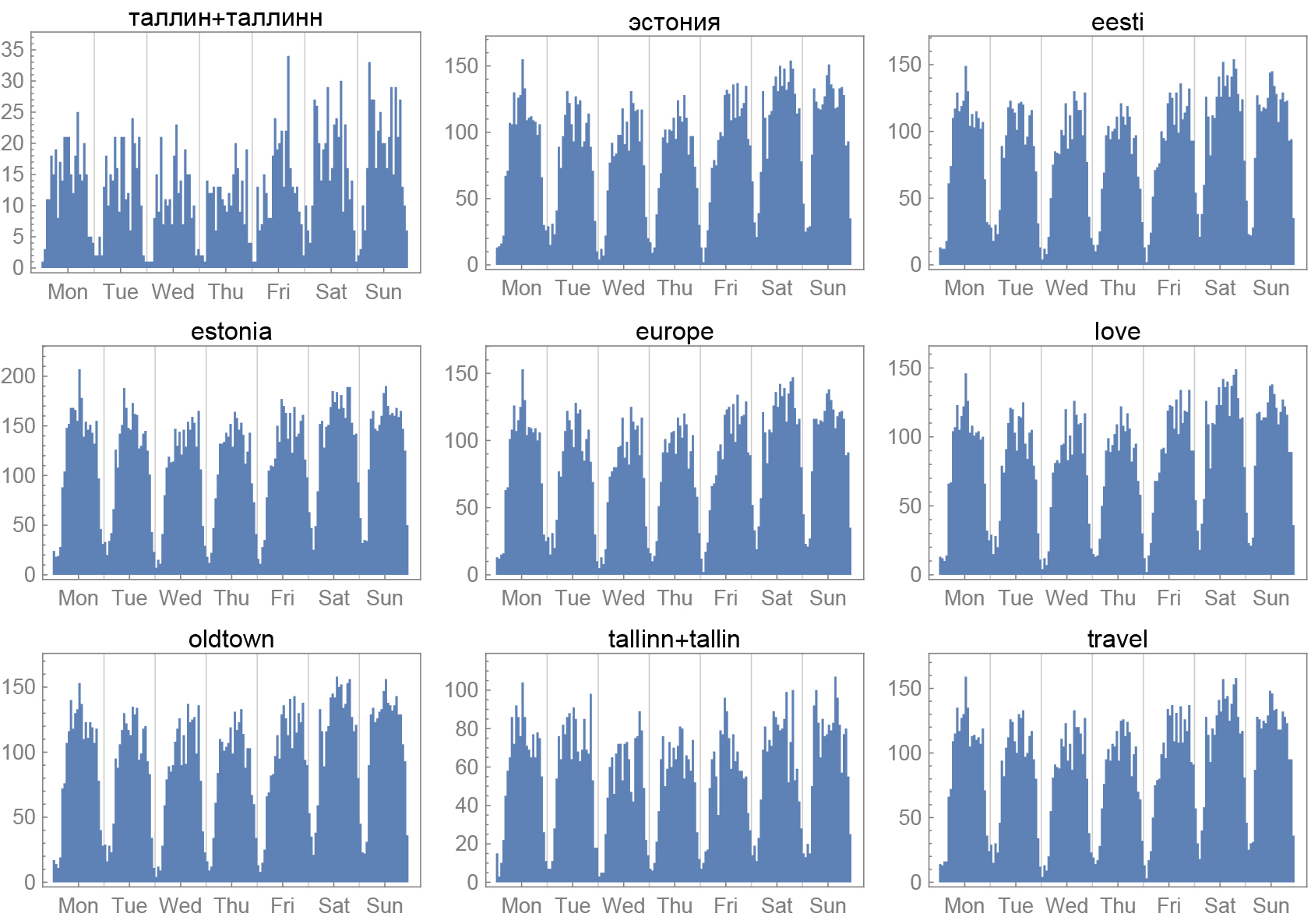

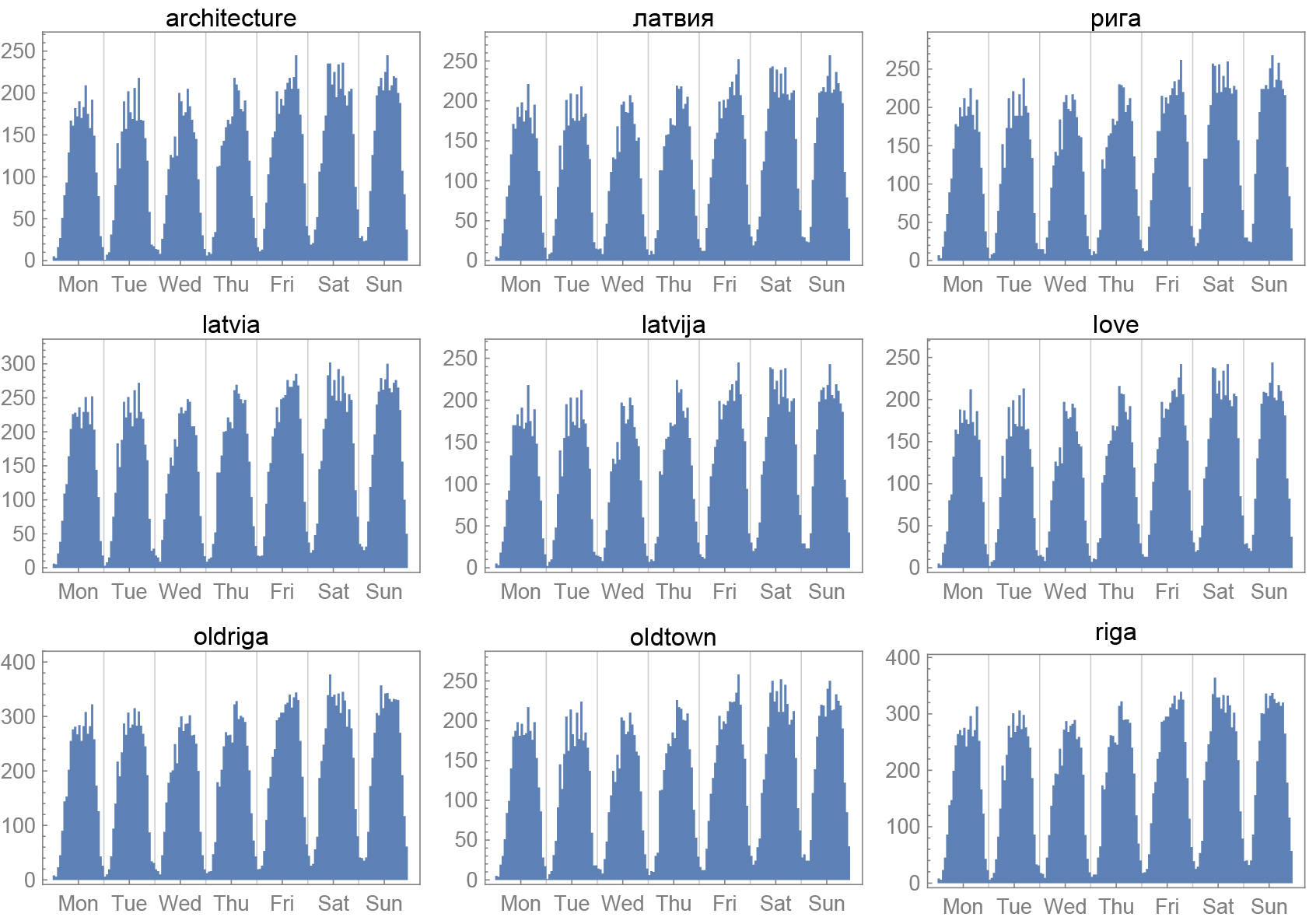

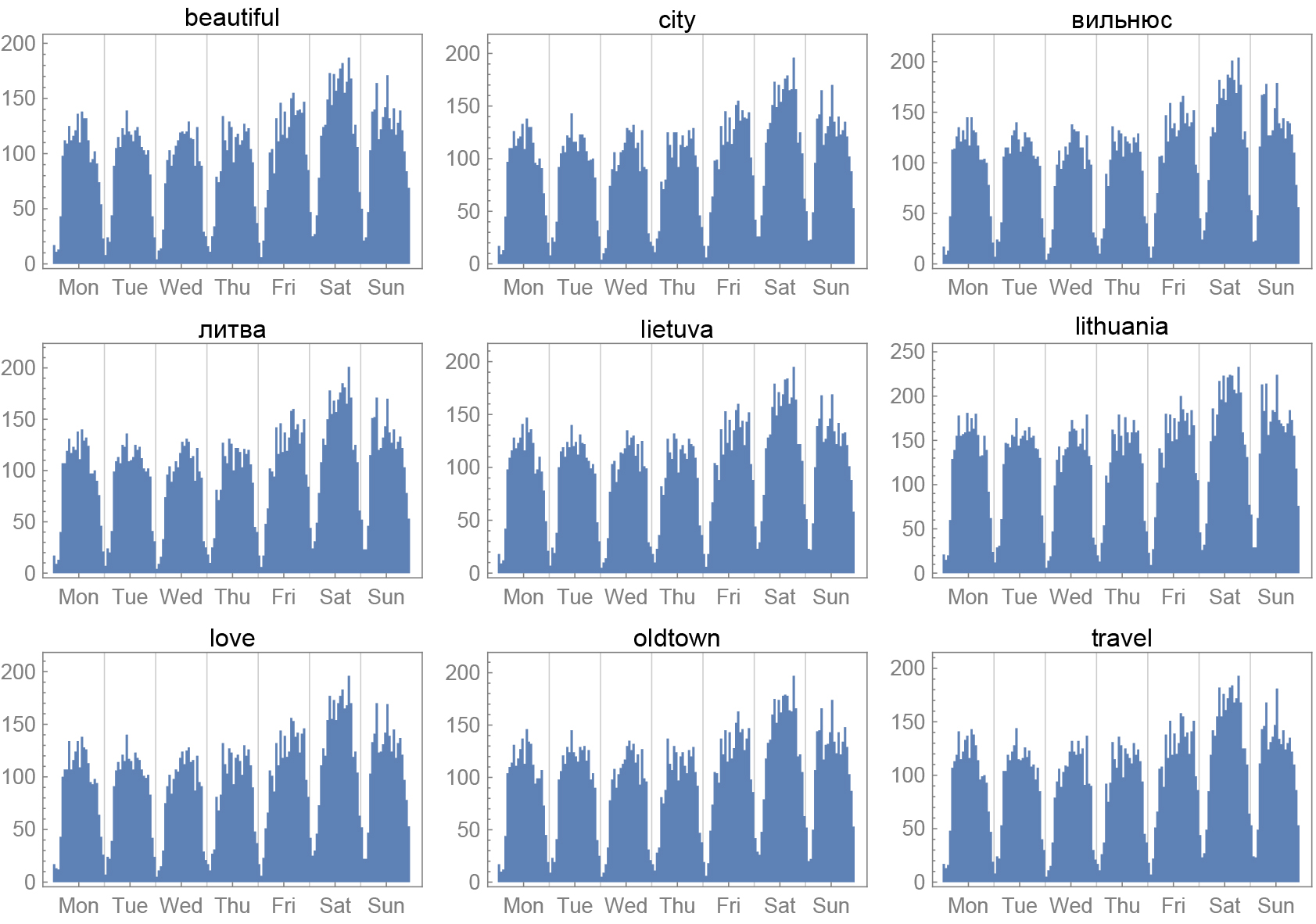

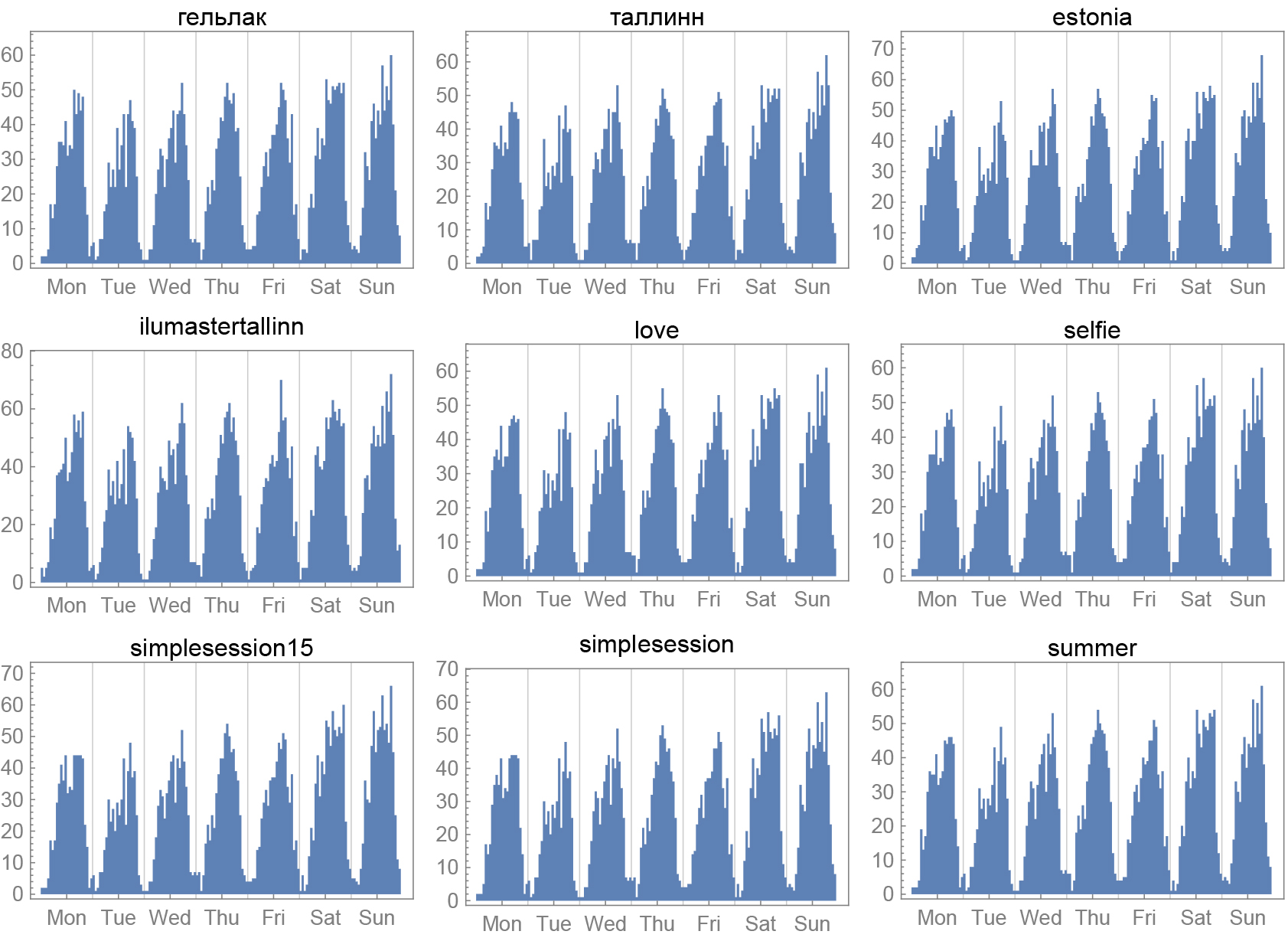

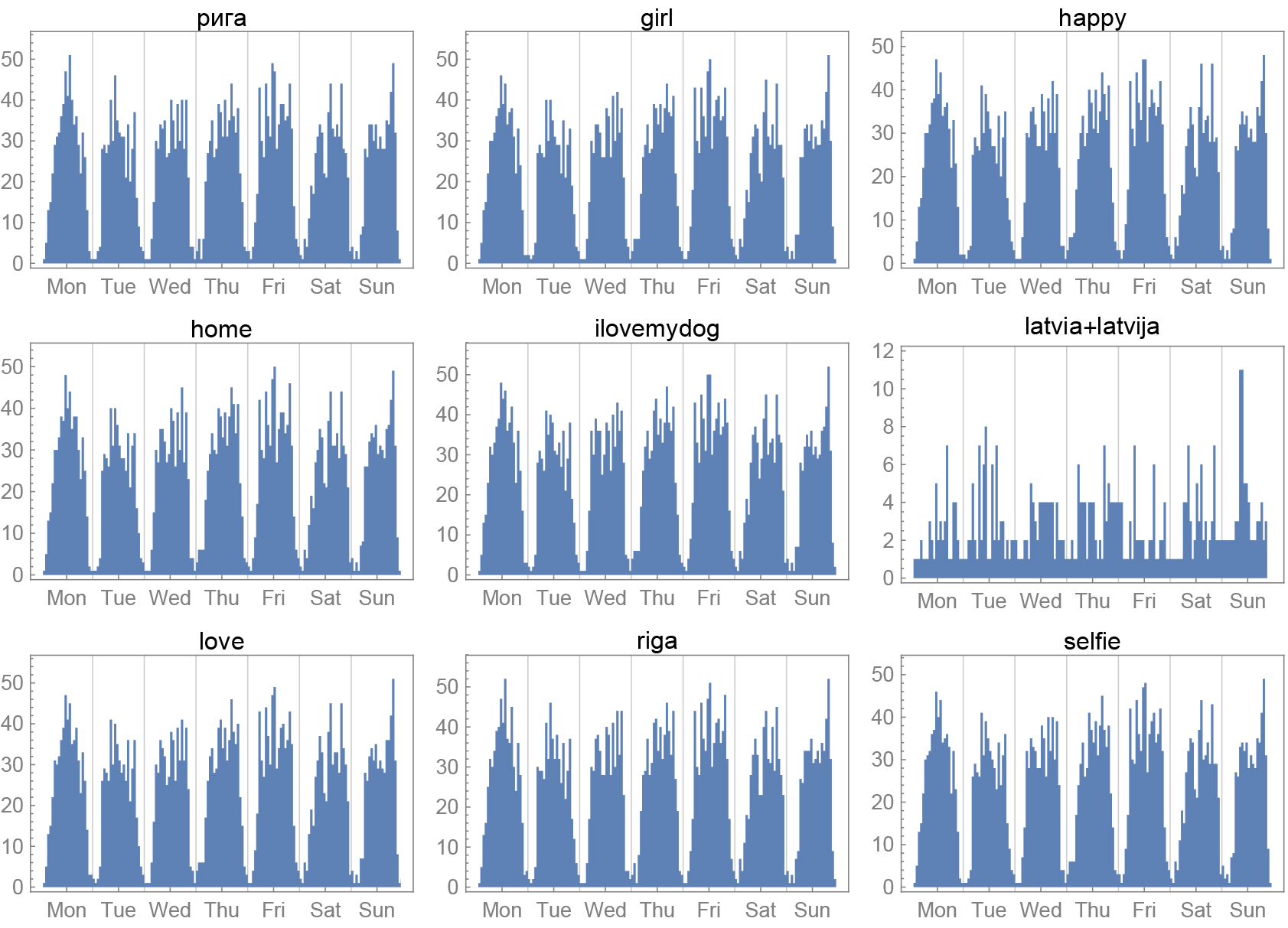

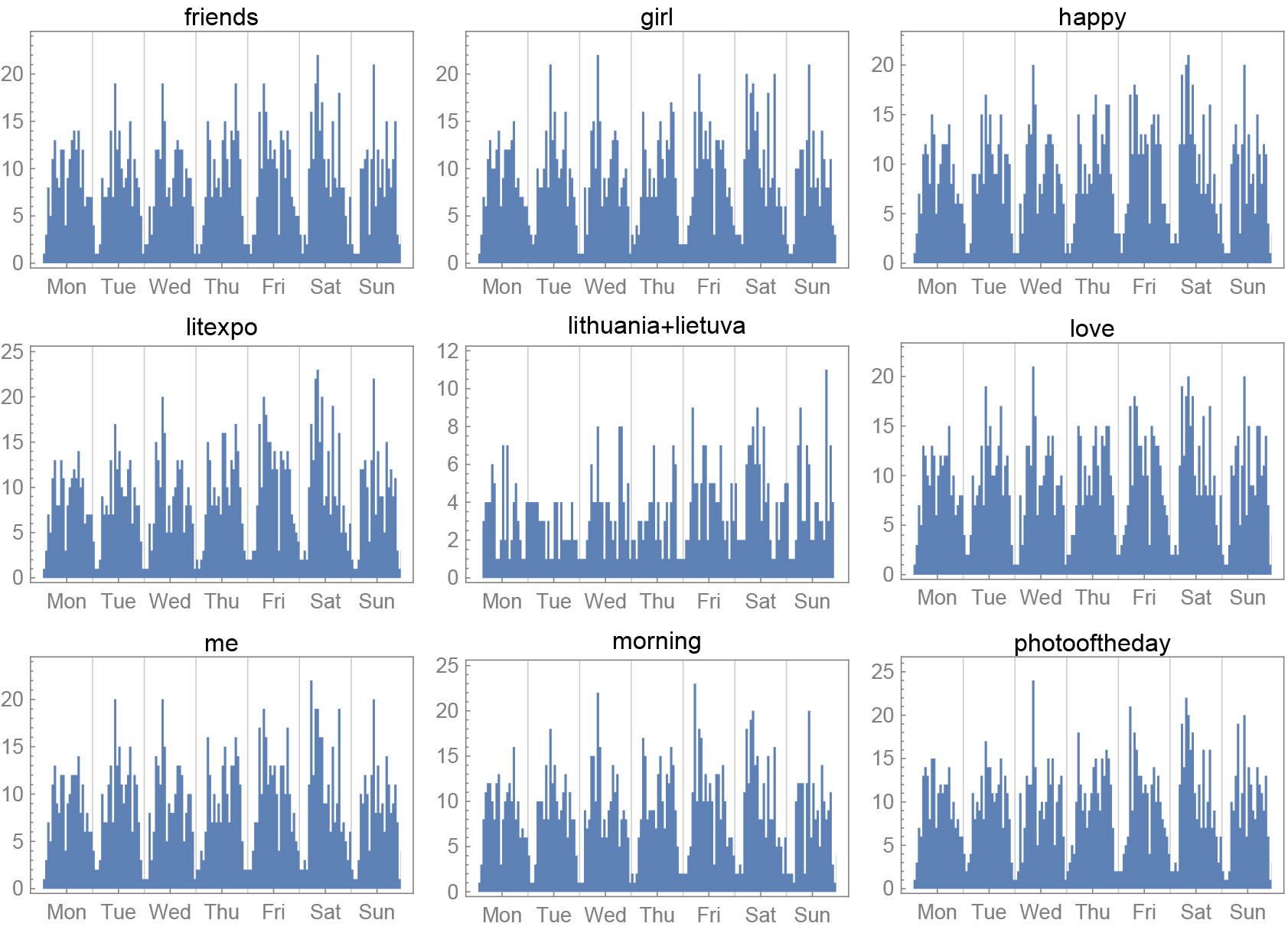

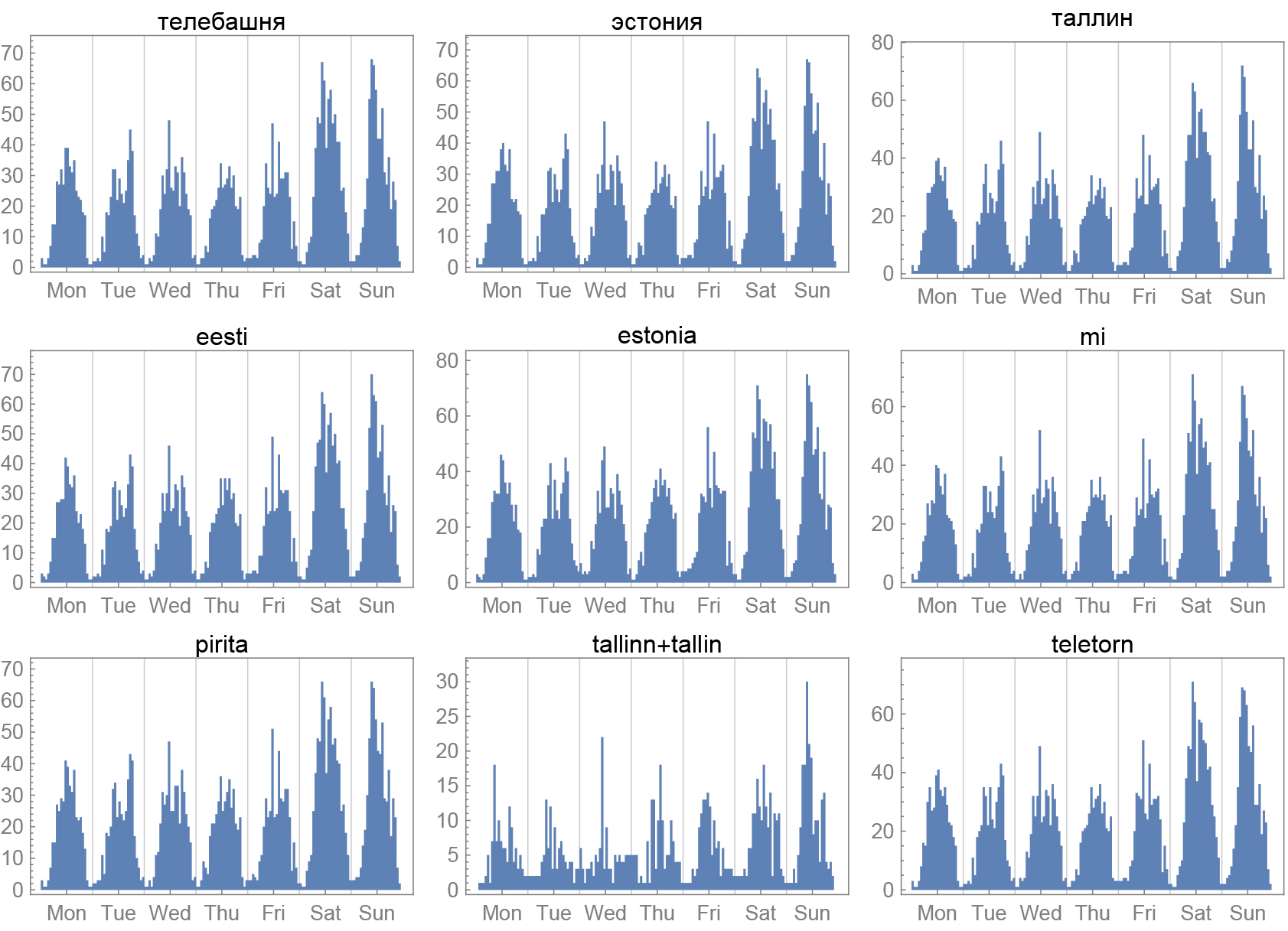

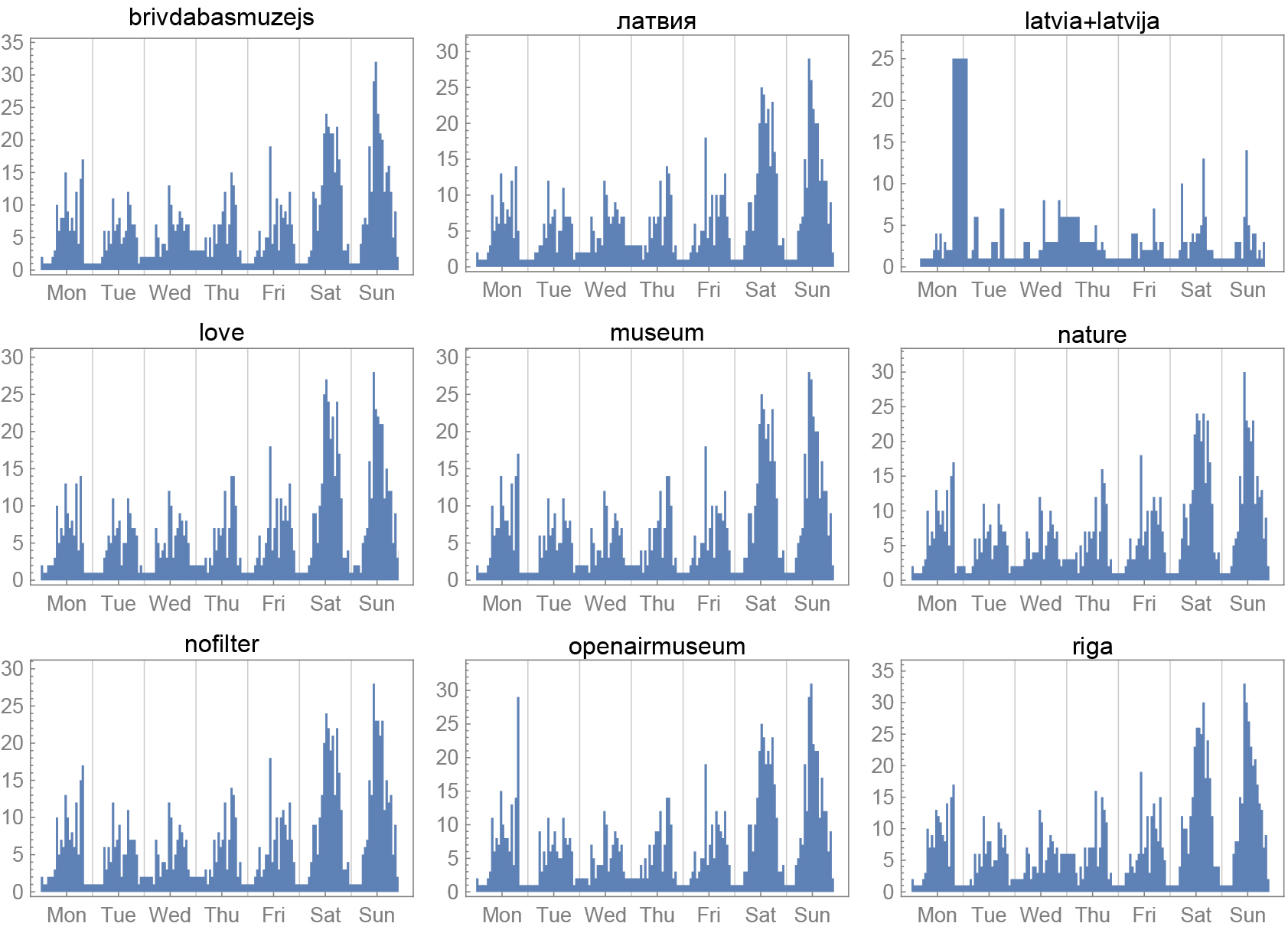

The following graphs show the number of pictures posted on Instagram every hour of the week, in each of the three cities sorted by hashtags.

A special thanks to Daniel Giovannini for the many conversations we had while writing this article and to help making this text flawless.

All images credit – Spin Unit

© Deep Baltic 2016. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.