by Zigmas Vitkus, VILNIUS

Aukštieji Paneriai, an idyllic hilly area about ten kilometres from the centre of Vilnius covered with slender pine trees and old oaks, was intended to become a resort. However, this did not happen; during the Second World War, Paneriai (Ponary in Polish; פאנאר in Hebrew), became, in the words of the Polish writer Józef Mackiewicz, “the incarnation of horror never seen before. When they hear the word ‘Ponary’, the six letters ending in ‘y’, many are overwhelmed”. Here, between 1941 and 1944, the Vilnius Special Squad and other Nazi units under the Nazi SD shot up to 70,000 people, most of whom were Jews from Vilnius. This is the largest number of any similar location in Nazi-occupied Lithuania. The area of the Soviet fuel base, on which construction started in 1941 (it was not completed), was used for the mass murder. Along with Jews, Polish anti-Nazi resistance fighters, Red Army soldiers captured by the German army, communists and others loyal to the Soviet regime, and Roma, as well as Lithuanians opposed to the Nazis, were killed at Paneriai. After the war ended, the Soviet government began to exploit the history of Paneriai for political purposes (like any other place); however, it did not become the most significant memorial in the Lithuanian SSR to victims of the Nazis.

When visiting the Paneriai Memorial, you would not at first glance be able to tell that it is a place with a complex history: the wide paved paths leading to the Soviet-style monument and the somewhat clumsily decorated mass murder pits, the plain yellow-brick former museum building, standing off-site, and the eight monuments (built here between 1990 and 2004) scattered throughout the hilly pine forest do not make the same impression as other notorious places associated with the Holocaust. There is no barbed wire, no barracks or foundations, no watchtowers or other iconic signs of concentration and death camps. However, this impression is deceptive: the modest “facade” of the Paneriai memorial hides a complex and dense history: the history of the mass murder carried out here and how it was commemorated. The “biography” of Paneriai also clearly reflects tendencies in the politics of history in the Soviet Union, and how these were overcome in the years of Lithuania’s rebirth.

The 1950s: a wasteland

The memories of Boris Rozin, a Moscow-based translator and journalist, who visited the former site of the mass murder, help us find out how Paneriai looked at the end of the 1950s: “I went to the Paneriai pits for the first time in September 1959. Forest and shrubs. Instead of death pits – large circles, covered with soil and overgrown, slightly deepened, and so reminiscent of a circus arena. The autumn wind lightly rustled the grass, which surprised me by its shade: the grass was bright green on one side and bright red on the other, just like blood. I asked the old woman caretaker sitting at the museum door: “Do you plant that two-coloured grass specifically in memory of those killed?” “Oh, no,” she replied, “it grows by itself, no one takes care of it.”1 Rozin went to Paneriai for a second time twenty years later, at the end of the ‘70s: “The heartbreaking place of remembrance was just as abandoned and the museum, a little wooden building, was empty; a lone visitor, accompanied by a dog, stood on the opposite side of the pit. It seemed to me like the monument was slightly sloping.”2

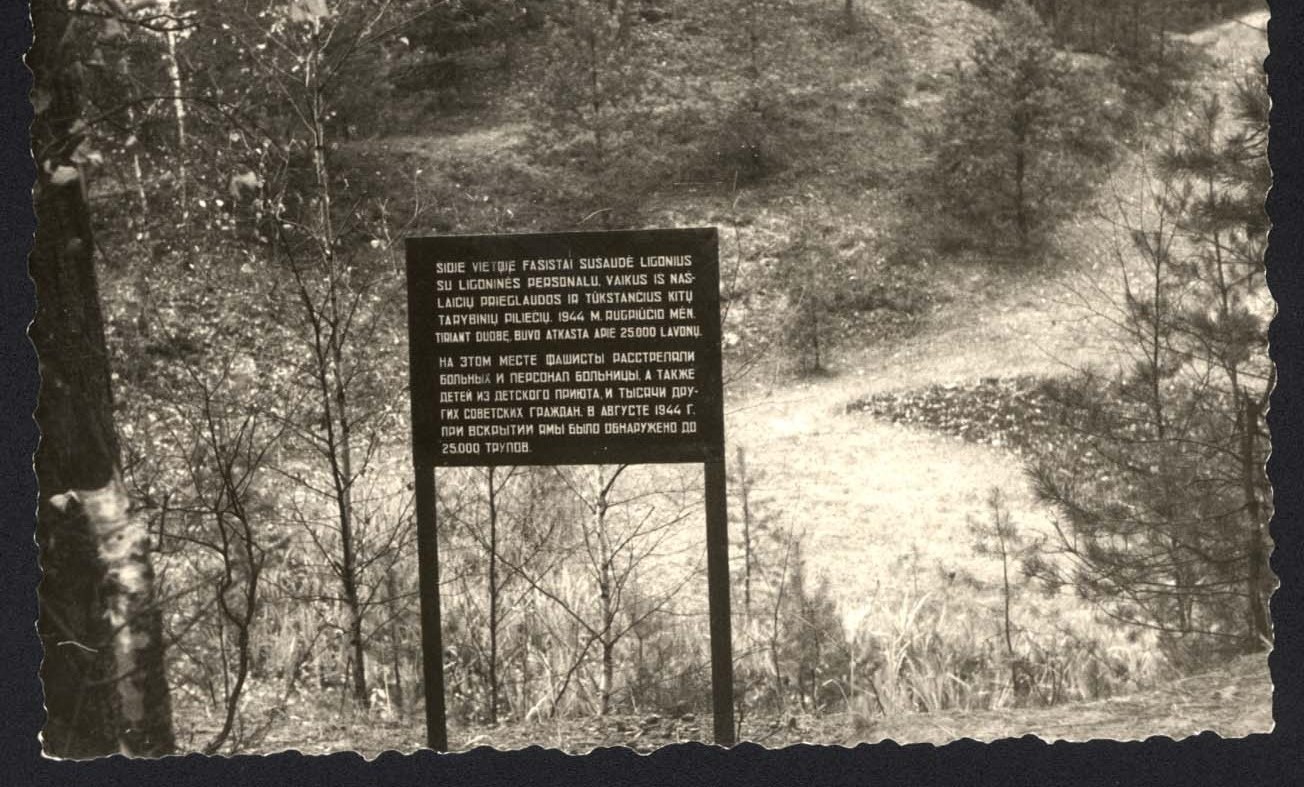

During the period from 1953 to 1959, the Soviet regime in Lithuania had little interest and concern for Paneriai (or for other similar places of mass murder). The biggest “job” carried out by the Soviet government on the site was the removal, between 1949 and 1952, of a monument built in 1948 on the initiative and funds of Vilnius Jews, and the construction of a standard obelisk with a star dedicated to the “Victims of Fascist Terror”, it seems on the foundations of the earlier monument. In the 1950s, this former site of mass murder might have looked like an ordinary quarry to those unaware of its history. In fact, the locals exploited the pits for utilitarian purposes, using the field stones with which the walls of the two pits had been laid for their own building needs, grazing animals in the forest and in the pits, and collecting berries and mushrooms there.

“We started grazing cows there when the Russians came,” recalled Jelena Jankowska-Korkowa, a resident of Paneriai. “We grazed them by the pits or in the pits. Mum used to wake me up at four in the morning to get the cows out. At ten o’clock we took them back for milking, and then carried the milk to the city.” This utilitarian use of the forest in which mass murder took place over a period of several years shows that part of the local population did not treat this place as a sacred space, and that they looked at it, so to speak, as ordinary and unremarkable. I would say not this was from ill will, but because of the limitations of the imagination. The fact that the authorities did not care to enclose at least part of the area of the former mass murder – to draw a physical and at the same time symbolic boundary to show that there were graves there – also helped it to look “normal”.

It was not only grazing of animals that went on in the former mass murder area. In 1954 Grigorijus Kabas, the chairman of the Vilnius Jewish religious community, addressed the Soviet authorities, sounding the alarm that the graves of Jews shot in Paneriai were “constantly being desecrated by unknown persons”. The inspector who went with him to the cemetery stated that in fact “every day unknown persons dig up the mass graves of Jews shot by Hitlerites”.3 In Kaunas in 1954, robbers pulled down 500 (!) matzevots in Žaliakalnis Jewish cemetery during the day, planning to use them to make stone monuments for Christian graves, and the area of the Jewish cemetery in Panemunė became a gravel quarry. The bones that appeared from the ground were collected and sold to “rag sellers”. In the 1950s the looting of cemeteries (not only Jewish ones) in Soviet-occupied Lithuania had become quite a common phenomenon, and to my mind could be explained by the worsening of moral norms in a post-trauma society. The profanation and looting of Jewish cemeteries were exceptional in that it was carried out cynically and openly, in the knowledge that there was basically no one to defend these places, and the government would not hurry to condemn looters.

However, there was a bit of confusion about Žaliakalnis, Panemunė and Paneriai. The inspector who visited Paneriai noticed that the situation with “brotherly graves” in Paneriai was provoking “outrage not only among Jews, but also among all honourable Soviet people”4 and called for the matter to be resolved as soon as possible. It seems that after correspondence between Lithuanian SSR agencies and with Moscow, Paneriai was tidied up (at least an order to do so was given to the Vilnius City Executive Committee). Probably at that time an order was given to the local government to fill in one of the two large mass murder pits where the Nazis had buried (uncremated) the last remains of Vilnius Jews shot in early July 1944. It was this pit that attracted the marauders, who were hoping to find there items they considered valuable. Incidentally, illegal excavations of this kind also occurred in the 1970s, even though by then there was already a museum there.

1960s: The regime’s focus grows

In the first 15 years after the war, not only Paneriai, but also all other sites of mass murder on the territory of Lithuania were neglected. The condition of graves of Red Army soldiers was similar, although they were officially given priority and one can find many orders and instructions “to bring order to this field”. During this period, the Soviet government in Lithuania had other concerns: seeking to establish themselves in the occupied country, suppressing Lithuanian partisan resistance, fighting “enemies of the People”, solving economic (“firewood and coal”) problems, and finally, in March 1953, trying to “re-calibrate” the power levers of the regime, after the death of dictator Joseph Stalin, who along with Vladimir Lenin, as we all know, was the cornerstone of the regime prior to this.

In 1956, after the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR Nikita Khrushchev condemned Stalin’s cult of personality at the famous 20th Congress of the Communist Party, the regime began to look for a new “big story” and more subtle ways of transmitting Soviet ideology than by unbridled repression and outright indoctrination. This big story became the narrative of the Great Patriotic War and the Soviet people’s victory in it, an integral part of which was the mass murder of Soviet citizens. Naturally, attention was also paid to sites associated with these murders. The Khrushchev regime, which took over the management of these places, pursued two goals: to demonstrate to society its concern for the objects of the past (and the past itself), with monuments that had simply been neglected until that time, and, perhaps most importantly, to establish its governance in Lithuania by sending a message to the Sovietised society and especially the younger generation: “If Lithuania had not been liberated by the Red Army, its society would have suffered the fate of the Paneriai victims.”5

It is no coincidence that in the 1960s, several grandiose memorial complexes (ensembles) were constructed in the USSR and its satellite states, and these could be considered essential features of the memorial cultures of these countries. In 1958 a memorial opened at Buchenwald (East Germany); in 1961 at Sachsenhausen (East Germany), and in 1967 at Auschwitz (Poland), as well as in Khatyn (the Belarusian SSR, 1969) and in Salaspils (the Latvian SSR, 1967) etc. The first place in the Lithuanian SSR that was brought to the attention of the Soviet regime was the Lithuanian village of Pirčiupiai, which was destroyed by the Nazis in June 1944. In the narrative of Soviet history, it was often compared to the destruction of the Czech village of Lidice in June 1942, the destruction of the French village of Oradour-sur-Glane in June 1944, and the annihilation of the aforementioned Khatyn in March 1943. All these villages and their inhabitants were killed in retaliation for attacks on German troops by local partisans.

Within the Soviet narrative, the history of the destruction of Pirčiupiai was meant to represent the crimes of the Nazi regime against the people of Lithuania. As early as 1957 a competition was announced for a monument in Pirčiupiai, and three years later Gediminas Jokūbonis’ sculptural composition Mother was completed and promoted. In addition, in 1958 the Museum of the Victims of Fascist Terror was opened at the Ninth Fort in Kaunas. In the same year, the establishment of a museum to the “victims of Fascist terror” was begun at Paneriai, and this was completed in 1960. True, the new museum only had two members of staff: head and guard; however, the fact that the government of the Lithuanian SSR decided to establish a museum here meant that authorities had noticed this place and its history as being important for their political purposes – firstly, to illustrate the fate of the Lithuanian nation and the Soviet people under the Nazi occupation.

The Museum was housed in a typical wooden trade pavilion. At first it belonged to the Museum of Local History of Vilnius (Vilniaus kraštotyros muziejus) and in 1962 it became a branch of the Museum of Revolution of the Lithuanian SSR. A small exhibition was placed there. Due to a lack of authentic exhibits, the exhibition was dominated by photographs of victims, which sought to give visitors – and this is the important thing – the impression that Paneriai was a place where Lithuanian intellectuals, communists, Soviet partisans, and prisoners of war were murdered. The aspect of the mass murder of Jews was not completely silenced in the exposition but existed in a “transformed” form: Jews became “people”, “men, women and children”, “residents of Vilnius” and “Soviet citizens”. This universalisation of the victims was meant to conceal the Jewish genocide, creating an impression that the object of Nazi repressions and terror was the whole of Soviet society – no particularities, only universalities.

Joan Isserman from the United States, whose parents had been born in Vilnius, visited Paneriai in 1966 with her husband and parents, and described a site that had been partially put in order: “It is very quiet now in Paneriai. Except for the crows. And you don’t become aware of the crows, of their ever increasing, never ceasing raucous cries until you have entered deep into the woodland […]. There was the broad path leading into the woods of Paneriai. There was the modest wooden sign at the right of the path, which said, first in the Lithuanian language and underneath in Russian, as is customary in this country, that here is the place more than 100,000 men, women and children from the city of Vilnius had been murdered by the Nazis […]. “Would you like to see the museum” our guide asked. It was a small building. On the walls, behind glass, were the exhibits. There were several photographs of skeletal bodies laid out side by side […]. There was a bowl of ashes and small solid fragments of bones, the remains of cremated human beings […]. As I turned from the pictures, the old lady attendant of the museum asked me in Russian if I would like to write something in the visitor’s book […]”.6 From her testimony, the reader may get an impression of an area that was quite well-maintained, compared with what Boris Rozin observed.

The 1960s: Architectural Competition

A wooden pavilion was brought to Paneriai and was described in official documents as a “temporary building” that would “soon” be replaced by a new, monumental museum. At the beginning of the 1960s, it might have seemed that this would indeed happen soon, and that Paneriai would become the second completed memorial to the victims of Fascism in the Lithuanian SSR (after Pirčiupiai). At the beginning of 1960, the Ministry of Culture of the Lithuanian SSR and the Union of Architects announced an “open tender for the preparation of a project for a monument at the former site of the mass murder at Paneriai”.7 The idea of an “open” competition – taken for granted today – was a great innovation in the Soviet state at that time: it reflected the freer creative atmosphere of the Khrushchev period. During the Stalinist era, architectural projects were implemented “from above”: by giving specific instructions to specific architects.

During preparation of the proposals for the architectural arrangement of the Paneriai Memorial Park-Museum, the architects had to offer solutions for the design of the entrances, the planning of the park, the arrangement of the pits, the architecture of the museum building and the fencing of the site. The architects were given freedom to design an area of 8.5 ha, using “various monumental-decorative art and garden-park architecture tools” for composition and architectural solutions. A total of 18 plans were received; from these, the idea of the group of architects from the Institute of Public Utility Design of the Lithuanian SSR, led by the young architect Jaunutis Makariūnas (b. 1934), was chosen as the best at the jury meeting held in December 1960.

The idea of this group of architects was praised for its concision and simplicity, as well as for its clarity, preservation of the natural environment and landscape, and cost-effectiveness. The Makariūnas group’s proposal reflected the trends developing in global architecture (and is still essentially not outdated). The idea was that any larger object within the area of the mass murder would be abandoned, and the whole site would be treated as a monument. It was proposed to concentrate the main elements of the ensemble – an architectural-sculptural path and the museum itself, which in their laconic forms were to make up a monumental whole – outside the area of the mass murder, so avoiding intrusion onto an authentic site of massacre.

The architects proposed connecting together the mass murder pits and trenches with paths, cleaning the pits themselves of the extraneous deposits and random vegetation that had accumulated over time, turfing (smoothing out) the edges of the pits, and planting the bottom with perennial flowers, emphasising that it was not only a mass murder pit, but also a grave. Interestingly, the architects proposed ringing the perimeter of the bottom of the pits with field stones, referring in the project description to the architecture of ancient Lithuanian graves (tumuli). A contour drawing depicting the people of different nationalities, ages and genders who had been destroyed was to be carved in the granite memorial wall near the entrance.8

The results of the Paneriai architectural competition were quite widely publicised: selected projects were exhibited at the Lithuanian SSR Architects’ Union, articles appeared in the press and professional publications, and a newsreel was created about the competition. It was declared that the memorial would be laid out in the coming years. Unfortunately, most projects selected during architectural competitions in the Lithuanian SSR (and in other Soviet republics) were not implemented due to lack of funds and lack of political will, and the architectural competitions themselves, as noted by architectural historian Darius Linartas, were mostly demonstrative9. Such a fate befell the winners of the Paneriai competition, Makariūnas and his colleagues.

The first attempt to revive the project to construct an architectural ensemble at Paneriai was made five years later. In 1965, the Council of Ministers of the Lithuanian SSR ordered the Vilnius City Executive Committee to arrange the site on the basis of the design of the Makariūnas group of architects. Construction work was planned to begin in 1967. This was the first of at least three subsequent stops in the planned work, which seemed to coincide (or “to coincide”) with important political events in the Middle East and the reactions of the Soviet regime to them. Renovation work on the memorial was meant to begin, but did not, first in 1967, then for a second time in 1971, and for a third time in 1973.

In the summer of 1967, as is well-known, the Six-Day War took place, after which the USSR severed diplomatic relations with Israel; in the autumn of 1971, Lithuanian Jewish activists organised unprecedented rallies at Paneriai, fighting for the right to leave for Israel; and in the autumn of 1973 the Yom Kippur War took place. It is unlikely that these events could have had a direct impact on the stalling of the Paneriai ensemble project, but there was some connection. Makariūnas, the architect of the Paneriai Memorial, also mentioned that USSR-Israel relations had influenced the “delay” of this project, saying: “If Israel is “for us”, we design and build. If not, everything is the other way around; the work stops”.10 This, by the way, indirectly demonstrated that the Soviet authorities were well aware that Paneriai was a place of exceptional importance to Jews.

The 1970s: stagnation

If the Khrushchev era was marked by a certain ethos of progress, the Brezhnev era is always referred to in historiography as a period of stagnation, characterised by indifference in all fields of society and life.11 Exactly the same can be said about the development of the Paneriai memorial during this period. At the beginning of 1980s, the situation seemed simply hopeless: the system’s enthusiasm for the complex arrangement of the memorial had waned, the “temporary museum” had become a “permanent” museum, and the “temporary” obelisk had become a “permanent” monument. In the press of the Lithuanian SSR, Paneriai was mentioned, if it was mentioned at all, among other Nazi terror sites, and the officials of the republic hardly ever stopped there. The most important remembrance ceremonies of “the Great Patriotic War” took place at Antakalnis Military Cemetery in Vilnius, near the grave of General Ivan Chernyakhovsky (commander of the 3rd Belorussian Front), and at the Kryžkalnis memorial (in Raseiniai district).

The atmosphere of Paneriai at the end of the 1970s is well reflected in the memories of Helena Pasierbska, a member of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa) who had left for Poland after the war, who visited Paneriai: “There was a hut by the road locked by an impressively sized lock. The inscription announced that it was “Paneriai Museum”. No opening hours were indicated. I decided to find the person who was taking care of this “museum” […]. I found a woman, a guard, rinsing empty bottles after a drinking session. Although she was drunk enough, she took me to the “museum”, before muttering something under her nose. As might be expected, it was a poor “museum” […]. A “Book of Victims of Fascism” – a list of names transcribed in Lithuanian without any data and dates was placed on the table. The guard explained all the negligence and inadequacy by saying that order would be introduced here in the undefined future”.12

This undefined future arrived in 1983, but here we have to mention one more event, which occurred at Paneriai on August 1, 1971.

On that day, a group of Vilnius Jewish activists, in conjunction with other Jewish activists in other cities in the USSR and Israel, organised an unauthorised meeting at Paneriai. The pretext for this meeting was commemoration of Tisha BʼAv (an annual Jewish fast day, dedicated to commemoration of the destruction of both Temples in Jerusalem) and the killing of Jewish intellectuals by the NKVD at the Lubianka prison in Moscow on 12 August 1952. The aim of this event was twofold: to draw the attention of the government to the neglect of sites of Jewish genocide and to press them to ease restrictions on the emigration of Soviet Jews to Israel. Several hundred people gathered at this meeting; they prayed, sung songs, and formed the Star of David with yellow flowers. After the meeting people were surrounded by the Soviet militia and dispersed, and ten Jews were arrested on charges of hooliganism. News of this event reached Western audiences.

The 1980s: renovation

The spur for reconstruction of the memorial at Paneriai was a fire in the museum, which destroyed the building. Although at the same time two similar large projects were being implemented in the Lithuanian SSR – the Ninth Fort memorial complex in Kaunas was being built and the Antakalnis soldiers’ cemetery was being reconstructed – funds were found for the renovation of Paneriai as well. Despite Paneriai not being prioritised (Makariūnas, who was entrusted with the implementation of the project, has said that due to a lack of materials for the Military Cemetery at Antakalnis, trucks came to pick them up from Paneriai), the project was at last completed within two years, albeit to a more limited extent than had been planned in the designs of the 1960s.

Visitors were greeted by wide asphalted paths leading to pits and trenches; the pits were architecturally decorated and granite walls with standard memorial inscriptions were installed nearby. Stairs led to some of the pits, and decorative flowers were planted at the bottom. In short, a recreational-memorial park had been created. A new museum building was also built – in the same place where the old one had stood, but this time of brick. It is interesting to mention that in official documents this was formally referred to as an outbuilding (ūkinis pastatas). This was due to the fact that at that time the USSR was experiencing a deeper than usual economic crisis and the government had temporarily suspended the construction of cultural buildings, and thus the Revolution Museum of the Lithuanian SSR had to try to find a legal way out of the situation.

I suppose this was one of the two main reasons why the Soviet press, already attentive to even the slightest (actual or alleged) achievements, did not pay much attention to the renovation of the Paneriai memorial, except for a small text in the Polish-language newspaper Czerwony Sztandar13. In neither the semi-official Tiesa (Truth), nor in the Komjaunimo tiesa (Truth of the Young Communist League), nor in the Vakarinės naujienos (Evening News) did the least news appear about the renewal of the Paneriai memorial. Another reason for this ignorance was that the Paneriai did not matter (very much) to the government, because there were more politically useful places in the Lithuanian SSR. The renovated site was “accepted” as an “ordinary” construction object, and this was really a stark contrast compared to the activities which were organised at the Ninth Fort in Kaunas a year before.

Why the Ninth Fort and not Paneriai?

I have mentioned that in the Soviet era many architectural projects remained on paper. In case of success, a long time almost always passed between the announcement of the results of the tenders and the start of work – especially for more complex projects that required larger “capital investments”. However, when considering the whole picture, it is clear that some projects were considered more promising than others by the Lithuanian SSR government. The Ninth Fort in Kaunas was one example. This was the second-largest Holocaust site in Nazi-occupied Lithuania, with about 50,000 victims (the ghetto in Kaunas (Vilijampolė) was established on 15 August 1941, with about 30,000 Kaunas Jews herded inside). Before the war the Ninth Fort had been a division of Kaunas Hard Labour Prison, where criminal and political prisoners were imprisoned, as well as people who were being punished administratively or held during the pre-trial period.

After an architectural competition had gone through four stages (1966–1970), an idea from sculptor Alfonsas Ambraziūnas, and architects Gediminas Baravykas and Vytautas Vielius was selected for the creation of a memorial complex at the Ninth Fort, which was finally completed in 1984. The opening of the Kaunas Ninth Fort Memorial, which took place on June 15 1984, was an important event that year in the Lithuanian SSR and was widely covered in the press, and in radio and film documentaries. Unsurprisingly, the monumental composition distinguished itself not only by its properly expressed ideological message (three complex groups of figures made of concrete represented the classical schema of Struggle, Death and Victory/Resurrection), but also by its grandeur and the mastery of its composition. The sculptural composition at the Ninth Fort was 32 metres high; the sculptor and architects shaped a magnificent monolith from unplaned planks using original technology.14

Why did the Lithuanian SSR government prioritise the Ninth Fort instead of Paneriai? Why did it at first seem that Paneriai was to be developed, and why did they later change their minds? When the “biographies” of Paneriai and the Ninth Fort are compared, all become clear. The Ninth Fort was more suitable for the spread of Soviet ideology for at least five reasons:

Firstly, because of the complexity of its history. During the Tsarist period, the fort functioned as one of the strongholds of Kaunas Fortress, which was directed towards imperial Germany. Secondly, from 1924 to 1940, under the independent Lithuanian state, there was a prison there, in which various members of the Communist Party of Lithuania were imprisoned. Thirdly, among the victims of the Ninth Fort there were indeed many “foreign nationals” (Jews from Austria, Germany, and France). This fact facilitated the internationalisation of the victims. The fourth reason why the Ninth Fort was more suitable for the government of the Lithuanian SSR was that in its history there is a clear dimension of resistance. In creating a narrative of history, Soviet ideologues were constantly looking for stories of resistance and victory. The fact that political prisoners (among them the future First Secretary of the Lithuanian Communist Party, Antanas Sniečkus) were imprisoned before the war in the same building complex as victims of the Nazi regime during the war was immensely helpful to Soviet ideologues. All of this could be easily linked into a single narrative, encompassing the years of Tsarist, “bourgeois Lithuanian”, and Nazi oppression, and resistance to it.

In this narrative of resistance, a central role was played by the events of December 1943, when there occurred an escape of 64 “burners” (prisoners forced by the Nazis to exhume and burn the remains of victims) – something of which all Soviet Lithuanian students were aware during the Soviet era. On April 15, 1944, a similar escape (after digging a tunnel from a pit-prison) was organised at Paneriai as well, but this did not become a symbol of resistance to the Nazi regime. Apparently, this was partly because Paneriai was unpopular compared to the Ninth Fort, and partly because the escape itself was only semi-successful: most of the fugitives were shot or caught on the massacre site.

The fifth reason why the Ninth Fort was more suitable for the Lithuanian SSR government was its strategic position. The Ninth Fort is easily accessible – it stands near the highway, in an open space which is very suitable for a monumental architectural composition.

But Paneriai was “simply” a place of mass murder in a remote, hard-to-reach place (a forest), where people were brought in, shot, and buried. It had no complex, dramatic history before the war. Although it was not only Jews who were killed in Paneriai, they made up the vast majority of the victims here, making the task of presenting the place as an “international grave” more difficult. Resistance was also almost non-existent at Paneriai. Bearing in mind all these factors, it is not surprising that the government of the Lithuanian SSR preferred the Ninth Fort to Paneriai. The preference for Pirčiupiai is also quite easy to explain – this was a place of the execution of 119 Lithuanians, a fact that fitted perfectly in the Soviet (Lithuanian) historical narrative. The relatively small number of victims (whose photos were displayed in the museum and whose biographies were known about) also had an influence – the fact that 119 killed people is easier to imagine and comprehend than tens of thousands of murdered “Soviet citizens” or “people”.

Paneriai during Lithuania’s rebirth: returned memory

Paneriai has never been a popular destination for visitors, with the exception of a short period towards the end of the ‘80s. The sudden increase in the number of visitors to the memorial in 1988 (28,000 visitors visited the memorial that year, compared to 10,000 in 1986, if we are to believe the statistics of that time) was related to Lithuania’s national rebirth and the events that this movement inspired. The anniversary of the escape of the so-called “burner’s brigade” was commemorated that year at Paneriai; Soviet Victory Day, at that time still an official holiday, was celebrated; two rallies of the Jewish community took place; and All Souls’ Day (Vėlinės) was marked. The name “Paneriai” began to emerge in public discourse as a place of the genocide of Lithuanian Jews (the term “Holocaust” was not used at that time).

One of the first signs of freedom at the Paneriai memorial took place on 9 May 1988, when a commemorative performance was organised by Griša Alpern, a young Jewish activist in Vilnius and later the inspiration for the Jewish organisation Tkuma. Alpern (whom I contacted by email several years ago) was inspired by the sense of injustice he experienced every year on 9 May, Victory Day, when “correct speeches” were heard in Paneriai about the “Soviet citizens” and “Soviet people” killed there. Alpern and his friends crafted 60 stars of David and placed them on sticks, ten for every million Jews killed during the Holocaust. The stars were successfully pinned to the pits, and although they were quickly removed, some people did manage to see them. Those who succeeded in seeing them were, in Alpern’s words, shocked. This act was quite a brave one. Let me remind you that this was after the unauthorised rally organised by Lithuanian dissidents at the Adam Mickiewicz Monument in Vilnius on 23rd August 1987, during which the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had been condemned (so the atmosphere was already freer), but that Sąjūdis (the Reform Movement of Lithuania) had not yet been established.

The official commemoration that took place at Paneriai on that same day – 9 May 1988 – was also special. It testified that the spirit of perestroika had reached the peripheries of the Soviet empire. For the first time, a representative of the authorities of the Lithuanian SSR acknowledged that the majority of the 100,000 victims at Paneriai (this was the official number that one would find in Soviet historiography and at the museum) were Jews. This was like giving permission to talk more and more freely about the Jewish genocide in Lithuania. Two months later, on 9 July 1988, a rally took place in Vilnius, on the site of the former Vilnius ghetto. The passing over in silence of the Jewish genocide and the need to talk publicly about the scale of the mass murder of Jews and need for monuments was openly discussed there. This meeting had a strong impact on the national consciousness of local Jews and gave them the courage to continue their activities, under the umbrella of Sąjūdis.

The year of 1988 was full of events in Lithuania, as was the following year. In September 1988, the first meeting in Paneriai took place on the site of the Paneriai memorial, during which the representatives of the still-Soviet Vilnius city government and the Lithuanian Jewish Cultural Society (Lietuvos žydų kultūros draugija) agreed on measures to “improve the memorial” at Paneriai. Specifically, a plan was made to build a new monument and add other architectural accents, indicating that most of the victims killed there were Jews from the city of Vilnius and its environs, as well as to supplement the museum’s exhibition. This kind of cooperation testified to the fundamentally changed political climate in Lithuania. A similar meeting would have been hard to imagine even a year before. A miracle had taken place before people’s eyes.

The very same year, on 25th September, the event “March of the Living” (Gyvųjų maršas) in Vilnius took place. The march started in the area of the former site of the Vilnius ghetto and later moved on to Paneriai. The whole philosophical and psychological significance of this march was summarised by the slogan “Jewish Nation Alive” which was exhibited on posters that were created for this event. The organisers brought a copy of the old Jewish monument made from cardboard that had been built by the Jewish community at Paneriai in 1948 and removed by the Stalinist regime several years later (as an intimation to the authorities that the monument had to be restored). On that day at Paneriai, a stirring poem, “Jurekas”, was recited, written by the Lithuanian diaspora poet Algimantas Mackus in memory of a friend of his who was killed at Paneriai.

After the 1988 rallies, physical memorials began to be put up at Paneriai, initiated by different communities of memory, and so a new topography of commemoration of the mass murder in Paneriai began to form – one which still exists today: in 1989, a black marble slab commemorating Jews killed at Paneriai was installed; in 1990, on the initiative of repatriates from the Vilnius region, a wooden cross was installed in memory of the Poles; In 1991, a monument to the Jews killed at Paneriai was unveiled, created by the aforementioned Jaunutis Makariūnas. A little later, in 1992, Lithuanians (86 soldiers of the Lithuanian Territorial Defence Force, shot by the Nazis at Paneriai and in Marijampolė in the spring of 1944) were memorialised. Twelve years later, a more substantial monument to these soldiers was unveiled at Paneriai, representing the Lithuanian segment (a small but symbolically significant one) of the victims at the memorial.

The insertion of the abovementioned black marble slab between the old Soviet-era stelae was only a “quick help” for memory. At that time, the Jewish Cultural Society was already taking care of the construction of a larger, more monumental memorial. The process of rebuilding the monument was not easy. The period of 1990–1991 was an exceedingly difficult one for Lithuania, both politically and economically – the state was fighting for survival. From April to July 1990, the USSR carried out an economic blockade of Lithuania. In the autumn of 1990 construction of the monument stopped (the foundation of the monument had been already laid) until the spring of the following year: because of lack of funds and the difficulty of obtaining the building material. In order to raise funds for the construction of a monument at Paneriai, a special fund was established at the expense of the Lithuanian Jewish Cultural Society. An Israeli businessman from Vilnius, Yeshayahu Epstein, contributed most actively to the construction of the monument. An honorary committee set up in Israel, which included Prime Minister Menachem Begin, historian Icchak Arad, poet Abraham Suckever and others, also helped to promote the restoration of the monument at Paneriai.15 The construction of this monument was completed in the spring of 1991 and was solemnly unveiled on 20 June. This day marked the official institutionalisation of Paneriai as a primary place of remembrance and primary Holocaust site in the memorial landscape of Lithuania. On the facade of a flat granite monument standing on a granite pedestal, a text in Hebrew and Yiddish was engraved on a marble slab, and a hexagonal star of non-ferrous metal was attached at the top. On the other side of the monument, in Lithuanian, English and Russian was inscribed: “To the eternal memory of 70,000 Jews from Vilnius and its environs who were killed and burned here in Paneriai by Nazi executioners and their helpers”. After the unveiling of the monument, the Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel demanded that in the inscription be written not “Nazi helpers” but “Nazi local helpers”, arguing in the same line that the Lithuanian government was trying to conceal the truth.16 It seems to me that this demand had little validity, but it still signalled the existence of tensions at that point and thereafter concerning the fact that some Lithuanian men participated in the Holocaust.

At the same time, it needs to be mentioned that along with the memory of the Jews killed in Paneriai, the memory of the Poles who perished here was also reclaimed, having been masked in the same way during the Soviet era. It is known that most of the Poles killed in Paneriai were members of the Home Army, which was seen by the Soviet regime as a hostile force. In 1990, at the initiative of Helena Pasierbska, the Lithuanian Union of Poles (Lietuvos lenkų sąjunga) submitted a request to Vilnius City Council to build – or more precisely, to restore – a monument to the Poles, which had been demolished (they argued) during the Stalinist regime around the same time as the monument to the Jews. The wooden cross and granite slab was consecrated in the last days of October 1990 and reconstructed to the monument ten years later. On this slab an inscription (only in Polish) was made: “In memory of many thousands of Poles murdered at Paneriai”. At this point there had been no studies carried out on the number of victims, and so a more or less accurate total was not known. It was claimed by Poles who had moved from Vilnius to Poland after the war that about 20,000 Poles were killed here (historians now speak about 1,500-2,50017).

During the national rebirth of Lithuania and the first years after the restoration of the Republic of Lithuania, the Kaunas Ninth Fort also became relevant as a Holocaust memorial site. In October 1988, one of the first rallies in memory of Jews killed here took place here, which was captured by photographer Antanas Sutkus in a memorable photography series, Pro Memoria: images from the meeting and the faces of former prisoners of Kaunas ghetto and partisans.18 The museum itself has acquired a new trajectory, becoming a museum of Lithuanian Occupations and Freedom Fights, with a strong component of Holocaust history. The fact that less than half of the exhibition area was dedicated to the Holocaust was called a scandal by some Jews of Lithuanian origin living in Israel and this was one of several criticisms of this kind of that time, trying to show that Lithuanian government was trying to avoid or disguise the difficult past.19 The slow pace of renaming monuments dedicated to “Soviet citizens” to “Jews” has also been criticised.

Here we do not have the opportunity to discuss in more detail the attitude of the Lithuanian government or Lithuanian society‘s attitude to the Holocaust, but to my mind the biggest problem of that liminal time (1988–1991) concerning the remembrance of the Jewish genocide in Lithuania was not “ill will” or a “desire to forget” a dissonant past, but the influence of old, yet still-prevailing conceptions and notions of the past, a focus on the losses of their own “tribe” during the Soviet occupation, virtually non-existent objective Lithuanian historiography about the Jewish genocide, and also – and this is very important – the fact that the majority of Lithuanian society, especially those born in the Soviet years, knew nothing or almost nothing about this tragedy. People knew Kaunas Ninth Fort (everybody at one time or another had visited this place), some of them knew Paneriai, but they knew them as abstract places, where “people” or “Soviet citizens” were murdered. That meant little… After regaining independence Lithuanian society gained the opportunity to learn to remember (or “imagine”) what had happened to Lithuanian Jews, and at the same time to perceive this event as a disaster for part of its nation. In this process of learning, visiting and experiencing, authentic Holocaust places took a crucial role. And the process continues.

1. Б. Розин, Ю. Фарбер, „Яма“, Независимый альманах ‚Лебедь‘, Но. 636, 2011 06 22, с. 10–11. Source online: http://lebed.com/2011/art5860.htm

3. October 26, 1956 – Inspector V. Suchockis’ report to B. Pušinis, Representative of the Council of Religious Cults LSSR under the USSR Council of Ministers, on the condition of the Paneriai graves, SLA, stk. 1771, inv. 192, f. 21, p. 151.

4. In the 31 May, 1954 appeal of B. Pušinis, Representative of the Council of Ministers of Religious Cults LSSR under the Council of Ministers of the USSR, to A. Sniečkus regarding the Kaunas Jewish Cemetery, SLA, stk. 1771, inv. 192, f. 21, p. 128

5. “Paneriai”, Tiesa, August 24, 1944, no. 41; P. Griškevičius, Keturi laisvės dešimtmečiai (Four Decades of Freedom), Vilnius, 1984, p. 26.

6. Joan Isserman, “The Crows of Paneriai. Lithuania‘s Babi Yar“, New World Review, April–May, 1967.

7. 18 January 1960 – Programme and conditions of the open competition to commemorate the mass victims of fascist terror in Paneriai for the preparation of the project, LLAA, stk. 87, inv. 1, f. 291, p. 1–4. The terms of the competition were published in January 1960 in the architecture magazine Statyba ir architektūra (Construction and Architecture).

8. S. Pipynė, “Konkurso memorialiniam Panerių parkui-muziejui sukurti rezultatai” (“Results of the Competition for the Paneriai Park-Museum Memorial”), Statyba ir architektūra, 1961, no. 2, p. 17.

9. D. Linartas, “Sovietinio laikotarpio architektūros konkursų raidos apžvalga”, Urbanistika ir architektūra, 2009, no. 33 (1), p. 41-43.

10. 11 February, 2015 conversation with J. Makariūnas. Personal archive of the author. See also I. Gudelytė’s article “Knight of Architecture Jaunutis Makariūnas”, Archiforma, 2012, No. 1–2 (50), p. 79.

11. Lithuania in 1940–1990. Occupied Lithuania…, p. 496

12. H. Pasierbska, Ponary. Wilenska Golgota, Sopot, 1993, p. 220

13. N. Duda, “Paneriajski Zespół Pomnikowy”, Czerwony Sztandar, 8 September, 1985, no. 208.

14. A. Ambraziūnas, Dekonstruktyvizmo pradmenys, Marijampolė, 2018, p. 27.

15. Y. Epstein, “Paminklas iškilo Paneriuose” (“Monument Emerged in Paneriai”), Lietuvos Jeruzalė (Jerusalem of Lithuania), 1991, No. 6.

16. A. Gefen, “An Intolerable Perversion of History”, The Jerusalem Post, 9 June, 1991.

17. Monika Tomkiewicz, Zbrodnia w Ponarach 1941–1944. Warszawa, 2008, p. 176; Monka Tomkiewicz, Więzienie na Lukiszkach w Wilnie, 1939–1953, Warszawa, 2018, p. 139.

18. A. Sutkus, Pro Memoria. Gyviesiems Kauno geto kaliniams (For the Living Prisoners of Kaunas Ghetto), Vilnius, 1997.

19. Abba Gefen, “An Intolerable Perversion of History”, The Jerusalem Post, June 9, 1991; A. Gefen, “Choosing Independence”, The Jerusalem Post, May 25, 1990; Epfraim Zuroff, “Discouraging Signs in Lithuania”, The Jerusalem Post, July 9, 1991. Dov Levin, “Lithuanian attitudes toward the Jewish Minority in the Aftermath of the Holocaust. The Lithuanian Press 1991-1992”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Fall 1993, p. 247-242. Thanks for these sources to writer and historian Chris Heath.

Dr. Zigmas Vitkus is a research fellow at the Institute of Baltic Region History and Archeology, University of Klaipėda (Lithuania), and a freelance columnist. He is a graduate of Vilnius University, Faculty of History and the Centre for Religious Studies and Research. His fields of interest are the politics of memory and the culture of memorials, with a focus on memorials in places of genocide. In 2019, he defended his doctoral thesis at Klaipėda University, Department of History on the topic “A Memorial in the Politics of Memory: The Case of Paneriai (1944–2016)”.

© Deep Baltic 2021. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.