Stories about supernatural beings seem to be something that is common to all cultures, handed down from generation to generation, perhaps most often as a way of explaining mysterious natural phenomena. Even in an age when belief in these kinds of traditional stories have declined, they are regular features of the fairy tales told to children, and are still rich sources of inspiration for creators of literature and film. First published in 2012 by Vilnius University Press, the map “Mythical Creatures in Europe” includes 213 creatures from the length and breadth of the continent. Categorising the creatures into a number of general groups by their form, nature and attitude towards humans, the map reveals both enormous variety across Europe and broad areas of similarity even between very distant cultures. In addition to universally recognisable figures such as giants and vampires, there are others that will be unknown to most outside the region where they are found, such as the sleipnir, saratan and barbegazi.

Deep Baltic’s Will Mawhood recently spoke to Giedrė Beconytė, Professor at the Institute of Geosciences at Vilnius University and among the initiators of the map, about collecting the necessary information and the ongoing project to create a similar map for Africa. Taking as its starting point a discussion of the folklore of Lithuania, famously the last country in Europe to be converted to Christianity, the conversation touches on the apparent ambiguity of mythical creatures in older cultures, the important distinction between witches and hags, and the impact of organised religion on folklore.

One description of the map states that it “also reveals some interesting trends of distribution of the creatures, like their great diversity in the British Isles or their specific cruelty in the Balkans”. Were you able to deduce any reasons for these qualities in these parts of Europe? Is there anything that would particularly characterise the Baltic states?

We made some assumptions concerning the variety and character of the creatures – mainly related to the diversity and character of landscapes and biological diversity. It looks like in regions of greater diversity, there are many places to hide and various noises are heard (wind in the trees, birds, rivulets) – this may create mental images of small animal-like creatures hiding there. Friendly nature gives birth to more benevolent creatures.

It is different in vast open spaces like deserts or bare mountains where there’s no place to hide. There, creatures (sand whirls, bats, snakes) are physically seen or have no visible shape at all. Extreme heat, cold or drought may be associated with evil forces. Of course, there must also be other, deeper reasons related to ethnic culture, but we believe that the characteristics of the place matter.

In Lithuania, the most common mythical creatures also have their own habitats. Imps are supposed to reside in bogs and swamps, fairy maidens (laumė in Lithuanian) are often associated with lakes and meadows where thick fogs are seen at dusk and dawn. Giants and devils leave their footprints on stones. Giants are usually mentioned in association with hills and lakes they have created. It could be said that our mythical creatures are indeed closely related to nature.

Household creatures like brownies are usually associated with different sounds: in an old wooden house, there would be cracking noises, and you could imagine that someone is walking around. And sometimes things are lost and you can blame it on a brownie or an imp.

The Baltics were famously among the last parts of Europe to be Christianised, as late as the 15th century in the case of Samogitia, and much later in parts of the countryside. Would that suggest that this region would be richer in terms of mythical creatures?

I don’t think so. In Lithuanian folklore, there are only seven mythical creatures, of which only one, the aitvaras, is rather specific. All the others are anthropomorphic and have analogues in the folklore of Christian countries: imps, hags, laumės (fairies), kaukai (brownies), giants and mermaids. In some sources the grass-snake is described as a mythical creature and this may be a relic of pagan beliefs – grass-snakes were considered sacred animals. Generally, Lithuanian creatures can be characterised as tangible, acting in a practical way, and often benevolent to benevolent people.

The Livonian coast in western Latvia is particularly associated with tales of werewolves, which I can see do not appear on the map, perhaps for reasons of space. Are there any other particularly interesting examples from this region which you were not able to include?

The map has been compiled to quite a small scale and there is a great variety of creatures. Pictures represent not individual types, but entire classes of creatures and sometimes apply to a region larger than a single country. On our map, there’s Suņpurnis, which also represents werewolves in in Latvia [also known as sumpurnis: a fierce forest-dwelling creature with the body of a man and the head of a dog, sometimes a bird]. Of course, there were creatures that we could not link to a particular place or find a reliable description of – about 25 out of 249 found.

There was a kind of snow creature somewhere – in Iceland, maybe, but we couldn’t really place it. We couldn’t find a precise description, but it was like a whirlwind of snow – something like that.

How much of a difficulty was there in ascertaining which creatures were really part of folklore, and which were inserted by later writers, perhaps for the aim of nation-building? Andrejs Pumpurs, author of Lāčplēsis, the Latvian epic written in the 19th century, created some Latvian gods himself (although others are attested elsewhere) – did you find any cases where the same had happened with mythical creatures?

This was the main challenge for the project team. All the information about the creatures had to be checked against several sources, including folklore studies. We did our best to identify true mythical creatures and to exclude those invented by known authors or transferred from other cultures (like the basilisk of Vilnius – not an authentic part of folklore).

It’s not authentic? Because I know it’s quite a famous creature in stories about Vilnius.

We think it came through fiction, because we don’t have such a creature as the basilisk mentioned in folklore. The only instance was the one living in Vilnius, so we believe it was just imported in later times from Europe. I think it was found in a description of the bastion by some author; so he mentioned the basilisk, and people started talking about it, but because it had been mentioned, not because they had seen it. We don’t have explanations of where they come from, where they are born – other countries, the origin countries for the basilisk, they explain how basilisks are bred.

It was not originally in Lithuania – we don’t have anything like that. We have the aitvaras, which has some of the features of a basilisk, but it never kills with its eyes. The aitvaras is unique in the sense that it doesn’t have a defined shape. It can be seen in the shape of a rooster. It can take the form of a fireball – ball lightning could be the origin or connected with it in some way. It can fly and brings wealth to its host.

And is that quite unique to Lithuania, or are there other countries that have a similar idea?

Don’t they have something similar in Latvia – the pūķis?

Pūķis is like a dragon, basically

So the aitvaras is quite unique.

You classify the creatures into four categories: malicious, ambivalent, neutral and benevolent. Many mythical creatures are ambivalent – being both potentially benevolent and potentially malevolent in their treatment of humans, or viewed differently in different cultures (dragons, for example, are viewed negatively in Russia, but often positively in the Balkans). We see the figure of a devil on the modern Lithuanian-Belarusian border. Kaunas is host to the only museum of devils in the world, and the 3,000 items in the museum show that this figure has often been considered very differently in Lithuania from elsewhere in Europe, at least in Christian tradition – while generally malevolent, devils are also presented as rather dim. Are there any other cases where the Baltic perception of a particular creature or archetype differs strikingly from how they are depicted elsewhere?

The Lithuanian fairy laumė is dangerous specifically to men, though often kind to women and children – especially those who are poor and kind, abused or lost. They are seen doing “feminine” works – weaving, spinning, washing clothes. If men are mean, their revenge is immediate and often disproportionately cruel.

Devils in most countries are not mythical creatures by our definition – they are spirits that religious people believe in.

The museum is quite a popular thing, and the guy who started it [Antanas Žmuidzinavičius], he began with samples of folk art. In Lithuania we have a tradition of wood carving, and since Lithuania became Catholic, many religious motifs are reflected in those carvings, including the Devil, but the Devil as an evil spirit. But also we have a much longer tradition of devils in our folk tales, in our folklore, and they are a different kind of thing. We even have a different word for them: the museum in Lithuanian is Velnių muziejus and velnias is a common word for all types of devil, and there is also kipšas, which is more like an imp, but it’s also evil – it’s not like a spirit; it’s more like a creature. It can be seen running around on the moors and in the swamps and forests, and playing practical jokes. It’s a bit foolish, and not so dangerous at all, unlike the Catholic devil.

So some of the devils in the Devils’ Museum in Kaunas, would they be more like imps, if you’re being strict?

I think so. But in the museum there are actual devils, like St. George killing a dragon, and sometimes the Devil is in the shape of a dragon, so that’s a devil.

Many countries have some sort of imp – there are several sorts of imp in Spain. We have the typical Lithuanian swamp imp in Poland too, but the Devil as a spirit is not included on the map.

They merged after Catholicism was brought to Lithuania; they just borrowed the image of an imp to represent a devil, or people who heard about this evil spirit, the Devil, they connected it in their mind with the image of an imp – this small evil thing known from folklore. From then on, our imps became more malicious, because of the stories about a devil that was really the manifestation of evil.

You know that Christianity took all the pagan traditions and festivals and adjusted them. Like Žolinės, a big festival which we had in Lithuania on Sunday, which is considered now a religious festival. I think it is Assumption in English, when the Virgin Mary is taken up to heaven. Now in Lithuania it is commonly celebrated in churches, but originally the same day was Žolinės, which was a festival for collecting herbs. People say thanks to the earth for the new plants, new herbs – they’re used for healing and it’s a time for collecting herbs for medicine. They have plenty of different meanings for it, but it’s a natural end of the summer, beginning of the autumn, connected with crops. What they did is that they made those plants and herbs important in Catholic tradition, so people bring grass and herbs to church to be blessed.

We see the Lithuanian tradition of kaukas in southern Latvia – perhaps there would also be some influence from the stories of Russian figures like the witch Baba Yaga in some places bordering on historically Slavic-populated areas. The influence of Finnish folklore in Estonia has been profound, most obviously on the Estonian national epic Kalevipoeg, which is heavily influenced by the Finnish Kalevala. What kind of influences can be observed from neighbouring cultures?

I don’t know the right answer here, but it seems that the influence of other cultures was not so large. The hag was apparently imported from Slavic countries. As I mentioned, Christianity modified our imp (kipšas) who became much more malicious. Laumė, previously neutral, developed a more pronounced attitude to humans – good to good people and mischievous to bad ones.

You made a distinction between witch and hag there. Is there a difference?

“Witch” is a very general word. Our witches – I would translate it as “witch” in English because there’s no better word for laumė; they are between witches and fairies – they can be either good or bad, and they’re very much like humans. Slavic hags are old ugly women who usually do bad things – Baba Yaga is a typical hag; it’s not the case with our Lithuanian witches. They are young girls or young women – they can be old and ugly, but rarely. Very often in folklore they are seen dancing, for example by a lake when the fog comes down; they are dancing and singing in the dusk, when you can’t see clearly. They come to people and they often help women, sometimes they help women with their babies and their work; sometimes they defend women, and they punish men very cruelly who are bad to women. Generally, they are not very kind to men.

Maybe this would be like a nymph in English.

They share some features, yes. There are many, many different types of witch in Europe. I would say that witches are known for their ability of witchcraft, and that’s not really the case with our laumės. They can kill men or cut off their skin, for example, but it’s not like they predict the future or give some qualities to a baby.

This is just an observation, but it does seem that some of the Lithuanian creatures you’ve described are more kind of neutral than British mythical creatures I’m familiar with, where they’re often just good or bad. It seems more common that they’re maybe good, maybe bad in different situations.

When I read about banshees, there was something that reminded me of our laumė.

OK, I think that’s an Irish tradition – I don’t know a lot about it.

It can be without a real shape but sometimes seen as a woman washing clothes in a lake, maybe screaming. They believe that hearing the banshee means someone will die, but itself it is neither good nor bad.

And I think that is characteristic of an old culture; it is the sign of a true creature coming from folklore – you know, it’s not wrapped in a layer of tales and legends created by people. It’s more like pure belief – something that sometimes can be seen somewhere and it looks like a woman or an animal, something without a specific attitude towards people.

You said it’s characteristic of an old culture?

I would say so, being neutral. I mean, if something is not neutral, it’s more likely that it’s invented by you – because it’s coming from your fear, or your love for something beautiful like a fairy or a unicorn. But if it’s neutral, it may have very ancient roots, with no embellishment done by various authors.

The hag, as you describe it, that would be a bit more similar to certain figures in Russian stories. That came in a bit later, you think?

I’m not sure about the time, but hags are rarely mentioned in [Lithuanian] folklore. You know, collections of folklore – they are just stories that have been collected; people go to villages and speak to old people and ask what they remember. Those sources are not very reliable in distinguishing.

In a way I’m quite surprised that there was not a lot of influence between cultures, because I would think that people tell stories, and if it’s a good story it will travel across languages.

I think folklore is very closely linked to language, so it’s quite difficult for it to travel. Like the basilisk: it also travelled, but it remained foreign. Like Baba Yaga, like the kikimora – a very nice Russian creature. We have parallels, but it hasn’t become ours, because it’s too late now; we can read about them in the sources, but folklore is more ancient. I think in some regions they seep in, but not very much so.

I suppose in the past most people didn’t travel very far beyond where they were born.

Yes, that is a reason.

We can see witches on many parts of the map. Are there any mythical creatures that are almost universal, featuring in almost every culture’s conception of the world?

Yes. Practically every culture has its versions of imps/devils, fairies and brownies.

As well as fairly familiar mythical beings like dragons, werewolves and centaurs, the map features exotic-sounding creatures like the bukavats, ramidreu and quinotaur. Do you have any personal favourites?

Absolutely. Some are really funny. I love the wolpertinger – an absolutely useless and strange hare-like creature. They have it in German-speaking countries, between Germany and Austria where there are mountains. It is curious because it is assembled from different parts of different real animals: a deer, a hare… it has wings.

Oh yes, that’s a very strange-looking animal. And you said it’s useless?

Absolutely. It’s just like any other animal, like a hare – it can be seen somewhere in the mountains, and the wolpertinger can also be seen. There is also the dahu. That’s a goat-like animal with legs of differing lengths. Because they have mountains and it is difficult for a goat to run parallel on a slope, they invented a creature with two legs shorter on one side. So it can be very efficient – in one direction.

The Lizun (licker) is a Slavic creature. That’s a small furry cat-like creature that licks whatever is in its way: people’s hair, the skin of cattle or dirty dishes. It does nothing specific, except licking everything.

Of the beautiful ones, I like the Slavic magic birds: Alkonost, Sirin and Gamayun. Of course, our Lithuanian aitvaras.

Among those that are scary, there’s the Alp-luachra in Ireland: a fairy that crawls into a sleeping person‘s stomach and feeds on the food they have eaten. There’s also the French killer snail (Lou Carcolh). An atrocious subterranean mollusc-like creature with a gaping mouth surrounded by long, hairy, slimy tentacles that can extend for miles and can catch humans. Closer to Latin cultures, they have clearer lines between good and evil.

I wonder why that is.

We can check, but I think not so many of them are neutral in southern Europe. Greece is a separate story.

[Looking at map] There are some very dangerous creatures, and there are some that are very good, very useful – but they are not so common. There are more evil ones: giants, dragons. Not like the dahu or the wolpertinger.

In Lithuania, the aitvaras is ambiguous, but the kaukas – a sort of brownie – just lives in a house and can play various practical jokes on people, but doesn’t do any serious harm, and also can do good things. It’s common in our folklore for creatures to help people who are poor or abused. And evil creatures can help too.

In Estonia, there’s a distinction between the mythology of the island of Saaremaa, where Suur Töll (described on your map as “a giant, kind and ready to help, but very hot-tempered”) is mentioned in folk tales, and the mainland, where the giant Kalevipoeg is at the root of a lot of folklore. Are there any other examples, in the Baltics or further afield, where one particular region has strikingly distinct folklore traditions, compared to the rest of the country?

We did not analyse the countries in such detail. Generally, some creatures are not evenly distributed in Lithuania, but I wouldn’t say that there are great differences.

In fact, a student of mine read many, many compendia of Lithuanian folklore, and she picked out all the references she could find – so that was thousands of references – and she mapped every reference to a mythical creature dot-by-dot. And what came out was that the density is not homogenous: the household creatures aitvaras and kaukas are not found around Vilnius or in southern and eastern Lithuania, but in central Lithuania. Because it is believed the aitvaras can bring wealth, and that part of Lithuania is considered to be wealthier. But that’s just my assumption; it’s not a scientific hypothesis.

Laumė is found in north-eastern Lithuania, where there are many lakes, and close to the Latvian border – we share this belief with the Latvians [a similar figure is called “lauma” in Latvian]. There are giants where we have hills, different curious shapes in the landscape. The hag is closer to the borders with Slavic countries. And undinė, a kind of mermaid: authentic mermaids are quite rare in Lithuania, but they’re by the big bodies of water like the Baltic Sea and the Curonian Lagoon. And devils and imps are concentrated in the area where the variety of landscape is greatest (Samogitia and hilly eastern Lithuania).

And would there be a reason for that?

We always say that if you have a very diverse landscape: small groves, small lakes, some small mounds or hills – some mist in the evening, rain in one place and no rain on the next hill. You can’t see a vast open space, and it’s easy to believe that someone is hiding somewhere. You hear different sounds, you see different shapes in the fog and mist. So this diversity brings a great variety of quite neutral creatures.

And if you have a large open space, like the Sahara Desert, what can you see there? It’s not possible to hide.

And related to that, you mentioned you were working on a similar map for Africa. It would be great if you could tell me a bit about that. First of all, how long have you been working on it?

Since 2018. But it’s not like we’re working on it all the time. It’s already quite informative – a group of students were very creative, and they did a very good job of finding those descriptions. Many of them are in French, and French is not a common language that people speak here.

It was much more difficult than Europe, and we had the feeling that we would not be able to find very many creatures, but actually we did. The final list is above 200, more or less the same number. In Europe we never found a mythical creature that was a plant, or half-plant, but in Africa there are plenty of them.

Yes, they’re quite different, aren’t they, the animals? That’s interesting.

You see here (the Sahara Desert), a desert area, and it’s empty – the same kind of creature, a type of genie, and nothing so special. No natural diversity, no diversity of creatures. And here, in the jungle, we have really, really strange animals. The wolpertinger wouldn’t look special among these African creatures.

I’m looking now for another creature, which has a very big foot. And when he’s sitting, he can raise it and shield himself from the sun.

Very useful. And is that neutral or good or bad, or just a feature of the landscape?

No relationship to people.

Did you notice any big difference between the kind of creatures you were finding in Europe and in Africa?

African mythical creatures are much more exotic to us, and many of them resemble African animals, as we see. Frogs, snakes, different kinds of birds, creatures in the shape of plants, as I told you. Some of them move, some of them don’t, but they are usually malicious. We didn’t do an analysis of it, but the general impression is that African creatures are more malicious.

Would the reason for that be that it may be a more dangerous natural environment than some places in Europe?

I think so. There are some creatures that are poisonous. Here, in Madagascar, there is something like a plant or a tree, but it can move and catch you. Some [creatures in Africa] are really benevolent, but not many of them.

In passing legislation about the role of AI within government and business, and how to define legal liability on the part of algorithms, the Estonian government has invoked the mythical creature of the kratt, a supernatural servant formed of hay or domestic tools which had to constantly carry out work for its owner. The contemporary writer Andrus Kivirähk has made kratts a feature of his fantastical works of fiction (recently filmed under the title November). Are there any other examples of people in the Baltic states or elsewhere drawing on older local traditions in recent scientific or artistic work?

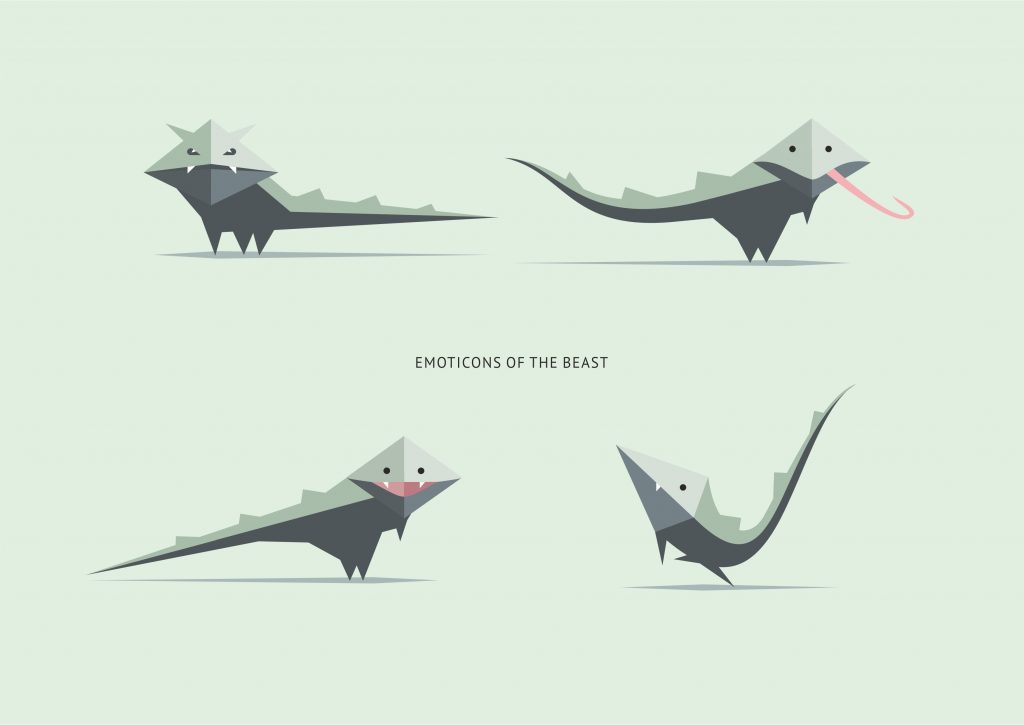

As far as I know, a contemporary magic beast of Kaunas is being created now by a team of young and creative people working for Kaunas Cultural Capital of Europe 2022.

They were looking for some good ideas for the cultural capital, some kind of urban myth, and the girl who started this project came across our map. She came and asked some questions about mythical creatures and how they arose, and she collected some ideas from our map. I don’t know the outcome yet; I’ve just seen a logo about the Kaunas Beast. But it will be a very modern creature, an IT-type creature. And you can imagine some small creatures living in internet cables, hidden in the electric current, why not?

It will be interesting to see if that’s successful. Maybe there could be some new, more IT-friendly mythical creatures in the future.

You should start telling your children tales about creatures like this, and they will remember and tell their children. And that’s how folklore is born. The condition is that a mass of people must believe it, and accept it as their story. So if we accept the Kaunas Beast, then it will become a new mythical creature.

And were there any cases your team came across of new mythical creatures appearing in recent decades?

No, we only investigated folklore sources for that project. We see all mythical creatures as extinct or most endangered species that have to be protected. But I would appreciate it if some creatures invented by authors started living their own life in modern folklore.

You can find out more about Giedrė Beconytė’s work at the Facebook page of the Department of Cartography and Geoinformatics at Vilnius University

© Deep Baltic 2021. All rights reserved.

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.