This is an extract from the novel Diary of a Jewish Girl by the Lithuanian author Saulius Šaltenis, originally published in 2015 and recently issued in English by Noir Press. Esther Levinson is being sheltered by a Lithuanian couple, Vladas and Milda, who have renamed her Eliza and are passing her off as their niece. When Eliza goes into town with Vladas, she witnesses the execution of a fellow Jew.

Some boys stand on a broken post by the high, barbed-wire-topped fence around the workshop, staring intently through a hole, as if something interesting is happening on the other side. There is only one hole and there are three boys, so they swap impatiently, not letting each other stay too long on the post.

Vladas Jomantas ties Zoja, the mare, up outside the hardware store.

‘I’m going to get a hand operated mill,’ he says to Eliza. ‘Then I’ll drop into the garage for some bulbs. I’ll ask about a battery – then we can have light even when there’s no wind blowing. Will you wait here?’

He asks then sternly, ‘So, girl, who are you?’

‘Eliza.’

Vladas disappears and is gone for a long time.

The boys glance across at the attractive girl in her blue and white sailor’s suit; she’s more attractive than the hole in the fence now and they wave, beckoning her to come and look through the hole. Eliza is dubious, but Vladas is not to be seen. Cautiously, she crosses the cobbled street. The boys help her up onto the pole. The older one encourages her, holding her so that she doesn’t fall, peeping up her legs and under her pleated skirt when she stands on tiptoes. At first Eliza sees only the rope through the hole, tied high, stretched and swinging sideways.

The boy who is so helpfully looking after Eliza, tilts his head back further and further and says, his voice hollow with excitement, ‘If you had come over straight away, you would have seen how they hanged the Jew. Can you see well? If the hole is too high, I can put a brick under your feet, or shall I lift you up? Can you see now?’

‘I can,’ says Eliza, though she can still just see the rope; pushing herself higher on her tiptoes, she sees a tuft of hair, ears and a face, wide like the full moon, with red eyes swollen from being beaten, the mouth open.

For some reason the face doesn’t scare Eliza; it looks more like a strange doll’s rather than a person’s. Eliza turns around. The boy blushes and lowers his eyes and helps her down from the post, leaning, as he does so, against her, as if by accident. Eliza’s skirt ripples and catches on the boy, lifting up like a curtain as her bare feet touch the ground.

‘Thank you, I’ve seen enough,’ Eliza says and walks back to Zoja and the cart, the boys watching in silence how the sailor’s skirt made by Milda swishes mesmerically left and right.

At last, Vladas returns with a hand operated mill for the grain, light bulbs and a bike dynamo in his hands.

‘I couldn’t get a battery,’ he says. ‘Now – to the hospital.’

Zoja pulls forward and the cart shudders down the cobbled street.

The boys stand by the fence with its secret hole, but they are not looking through it any more; instead they watch as the unfamiliar girl moves away in the cart.

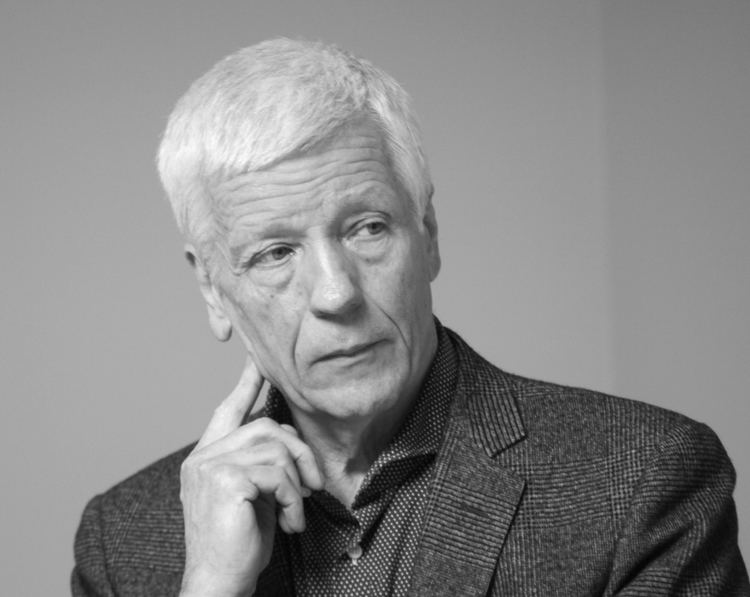

Saulius Šaltenis is one of Lithuania’s most prominent writers, author of numerous novels and screenplays, including the much-loved Nut Bread.

Šaltenis was born in Utena, Lithuania in 1945. His parents were both teachers and brought him up with a love of language and of Lithuanian authors, particularly Antanas Vienuolis, his father’s uncle, and the legendary poet-priest Antanas Baranauskas, who was also a distant relative.

He was drafted into the Soviet army during his university years and when he had completed his national service he made the decision not to return. Instead, he went on to carve out a position as one of the most prominent writers of Soviet Lithuania.

Šaltenis became not only a noted novelist, a skilled craftsman of sharply observed novels, but also a screenwriter. His writing for cinema left an indelible mark on his developing literary style. His narrative style has often been described as cinematic or imagistic.

‘His work was a true rejection of the sodden, syrupy, and verbose Lithuanian epic narrative,’ Jūratė Sprindytė writes. ‘Šaltenis does not describe or summarize, and he detests any narrative ‘ballast.’ Rather, he expresses himself in flashes of tropes, strokes of paradox, and rapidly shifting scenes.’

When the Lithuanian independence movement, Sąjūdis, began to emerge in the late 1980s, Šaltenis quickly rose to be one of the leaders of the struggle against Soviet oppression. His political activities continued after the fall of the Soviet Union and he became Minister of Culture in 2010.

Šaltenis is one of the few modern Lithuanian writers who has attempted to tackle the country’s dark history in its relationship with its Jewish minority.

Before the Second World War, Lithuania was home to a thriving, important Jewish population. During the war, 96% of that population were murdered, many in the forests outside small towns, as depicted in Šaltenis’ novel Diary of a Jewish Girl published in English this year.

‘There is a huge pain,’ Šaltenis has written. ‘It aches like an arm amputated a long time ago. The Jews were citizens of Lithuania, they are its historic past.’

Diary of a Jewish Girl is available now from Noir Press

Translated by Marija Marcinkute

Header image – Monument to the Holocaust in Šeduva, Lithuania [Image: Vilensija, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 Licence]

Like what Deep Baltic does? Please consider making a monthly donation – help support our writers and in-depth coverage of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Find out more at our Patreon page.